Distinct High Resolution Genome Profiles of Early Onset and Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes

Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes by Sayed Mohsen Hosseini A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by S. Mohsen Hosseini 2014 Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes Sayed Mohsen Hosseini Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. Several lines of evidence suggest a genetic contribution to the risk of DR; however, no genetic variant has shown convincing association with DR in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). To identify common polymorphisms associated with DR, meta-GWAS were performed in three type 1 diabetes cohorts of White subjects: Diabetes Complications and Control Trial (DCCT, n=1304), Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR, n=603) and Renin-Angiotensin System Study (RASS, n=239). Severe (SDR) and mild (MDR) retinopathy outcomes were defined based on repeated fundus photographs in each study graded for retinopathy severity on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) scale. Multivariable models accounted for glycemia (measured by A1C), diabetes duration and other relevant covariates in the association analyses of additive genotypes with SDR and MDR. Fixed-effects meta- analysis was used to combine the results of GWAS performed separately in WESDR, ii RASS and subgroups of DCCT, defined by cohort and treatment group. Top association signals were prioritized for replication, based on previous supporting knowledge from the literature, followed by replication in three independent white T1D studies: Genesis-GeneDiab (n=502), Steno (n=936) and FinnDiane (n=2194). -

Supplementary Materials

DEPs in osteosarcoma cells comparing to osteoblastic cells Biological Process Protein Percentage of Hits metabolic process (GO:0008152) 29.3 29.3% cellular process (GO:0009987) 20.2 20.2% localization (GO:0051179) 9.4 9.4% biological regulation (GO:0065007) 8 8.0% developmental process (GO:0032502) 7.8 7.8% response to stimulus (GO:0050896) 5.6 5.6% cellular component organization (GO:0071840) 5.6 5.6% multicellular organismal process (GO:0032501) 4.4 4.4% immune system process (GO:0002376) 4.2 4.2% biological adhesion (GO:0022610) 2.7 2.7% apoptotic process (GO:0006915) 1.6 1.6% reproduction (GO:0000003) 0.8 0.8% locomotion (GO:0040011) 0.4 0.4% cell killing (GO:0001906) 0.1 0.1% 100.1% Genes 2179Hits 3870 biological adhesion apoptotic process … reproduction (GO:0000003) , 0.8% (GO:0022610) , 2.7% locomotion (GO:0040011) ,… immune system process cell killing (GO:0001906) , 0.1% (GO:0002376) , 4.2% multicellular organismal process (GO:0032501) , metabolic process 4.4% (GO:0008152) , 29.3% cellular component organization (GO:0071840) , 5.6% response to stimulus (GO:0050896), 5.6% developmental process (GO:0032502) , 7.8% biological regulation (GO:0065007) , 8.0% cellular process (GO:0009987) , 20.2% localization (GO:0051179) , 9. -

Protein Interaction Networks and Their Applications to Protein Characterization and Cancer Genes Prediction

Ramón Aragüés Peleato Protein interaction networks and their applications to protein characterization and cancer genes prediction PhD Thesis Barcelona, May 2007 1 The image of the cover shows the happiness protein interaction network (i.e. the protein interaction network for proteins involved in the serotonin pathway) ii Protein Interaction Networks and their Applications to Protein Characterization and Cancer Genes Prediction Ramón Aragüés Peleato Memòria presentada per optar al grau de Doctor en Biologia per la Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Aquesta Tesi Doctoral ha estat realitzada sota la direcció del Dr. Baldo Oliva al Departament de Ciències Experimentals i de la Salut de la Universitat Pompeu Fabra Baldo Oliva Miguel Ramón Aragüés Peleato Barcelona, Maig 2007 The research in this thesis has been carried out at the Structural Bioinformatics Lab (SBI) within the Grup de Recerca en Informàtica Biomèdica at the Parc de Recerca Biomèdica de Barcelona (PRBB). The research carried out in this thesis has been supported by a “Formación de Personal Investigador (FPI)” grant from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia awarded to Dr. Baldo Oliva. A mis padres, que me hicieron querer conseguirlo A Natalia, que me ayudó a conseguir hacerlo ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................................................................... -

RNF2 Antibody Order 021-34695924 [email protected] Support 400-6123-828 50Ul [email protected] 100 Ul √ √ Web

TD7403 RNF2 Antibody Order 021-34695924 [email protected] Support 400-6123-828 50ul [email protected] 100 uL √ √ Web www.ab-mart.com.cn Description: E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that mediates monoubiquitination of 'Lys-119' of histone H2A (H2AK119Ub), thereby playing a central role in histone code and gene regulation. H2AK119Ub gives a specific tag for epigenetic transcriptional repression and participates in X chromosome inactivation of female mammals. May be involved in the initiation of both imprinted and random X inactivation (By similarity). Essential component of a Polycomb group (PcG) multiprotein PRC1-like complex, a complex class required to maintain the transcriptionally repressive state of many genes, including Hox genes, throughout development. PcG PRC1 complex acts via chromatin remodeling and modification of histones, rendering chromatin heritably changed in its expressibility. E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity is enhanced by BMI1/PCGF4. Acts as the main E3 ubiquitin ligase on histone H2A of the PRC1 complex, while RING1 may rather act as a modulator of RNF2/RING2 activity (Probable). Association with the chromosomal DNA is cell-cycle dependent. In resting B- and T-lymphocytes, interaction with AURKB leads to block its activity, thereby maintaining transcription in resting lymphocytes (By similarity). Uniprot:Q99496 Alternative Names: BAP 1; BAP1; DING; DinG protein; E3 ubiquitin protein ligase RING 2; E3 ubiquitin protein ligase RING2; E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RING2; HIP2 interacting protein 3; HIP2- interacting protein 3; HIPI 3; HIPI3; Huntingtin interacting protein 2 interacting protein 3; Huntingtin-interacting protein 2-interacting protein 3; OTTHUMP00000060668; Polycomb M33 interacting protein Ring 1B; Polycomb M33 interacting protein Ring1B; Protein DinG; RING 1B; RING 2; RING finger protein 1B; RING finger protein 2; RING finger protein BAP 1; RING finger protein BAP-1; RING finger protein BAP1; RING1b; RING2_HUMAN; RNF 2; Rnf2; Specificity: RNF2 Antibody detects endogenous levels of total RNF2. -

Product Data Sheet

For research purposes only, not for human use Product Data Sheet RNF2 siRNA (Human) Catalog # Source Reactivity Applications CRH4092 Synthetic H RNAi Description siRNA to inhibit RNF2 expression using RNA interference Specificity RNF2 siRNA (Human) is a target-specific 19-23 nt siRNA oligo duplexes designed to knock down gene expression. Form Lyophilized powder Gene Symbol RNF2 Alternative Names BAP1; DING; HIPI3; RING1B; E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RING2; Huntingtin-interacting protein 2-interacting protein 3; HIP2-interacting protein 3; Protein DinG; RING finger protein 1B; RING1b; RING finger protein 2; RING finger protein BAP-1 Entrez Gene 6045 (Human) SwissProt Q99496 (Human) Purity > 97% Quality Control Oligonucleotide synthesis is monitored base by base through trityl analysis to ensure appropriate coupling efficiency. The oligo is subsequently purified by affinity-solid phase extraction. The annealed RNA duplex is further analyzed by mass spectrometry to verify the exact composition of the duplex. Each lot is compared to the previous lot by mass spectrometry to ensure maximum lot-to-lot consistency. Components We offers pre-designed sets of 3 different target-specific siRNA oligo duplexes of human RNF2 gene. Each vial contains 5 nmol of lyophilized siRNA. The duplexes can be transfected individually or pooled together to achieve knockdown of the target gene, which is most commonly assessed by qPCR or western blot. Our siRNA oligos Application key: E- ELISA, WB- Western blot, IH- Immunohistochemistry, IF- Immunofluorescence, FC- -

WO 2015/065964 Al 7 May 2015 (07.05.2015) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/065964 Al 7 May 2015 (07.05.2015) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agents: KOWALSKI, Thomas, J. et al; Vedder Price C12N 15/90 (2006.01) C12N 15/113 (2010.01) P.C., 1633 Broadway, New York, NY 1001 9 (US). C12N 15/10 (2006.01) C12N 15/63 (2006.01) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (21) International Application Number: kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, PCT/US2014/062558 AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (22) International Filing Date: DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, 28 October 2014 (28.10.2014) HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (25) Filing Language: English KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (26) Publication Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (30) Priority Data: SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 61/96 1,980 28 October 20 13 (28. 10.20 13) US TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. 61/963,643 9 December 2013 (09. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

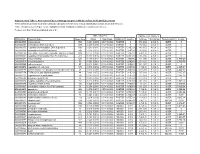

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Stranded DNA and Sensitizes Human Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma

RESEARCH ARTICLE Exosome component 1 cleaves single- stranded DNA and sensitizes human kidney renal clear cell carcinoma cells to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor Qiaoling Liu1†, Qi Xiao1†, Zhen Sun1†, Bo Wang2†, Lina Wang1, Na Wang1, Kai Wang1, Chengli Song1*, Qingkai Yang1* 1Institute of Cancer Stem Cell, DaLian Medical University, Dalian, China; 2Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, DaLian Medical University, Dalian, China Abstract Targeting DNA repair pathway offers an important therapeutic strategy for Homo sapiens (human) cancers. However, the failure of DNA repair inhibitors to markedly benefit patients necessitates the development of new strategies. Here, we show that exosome component 1 (EXOSC1) promotes DNA damages and sensitizes human kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) cells to DNA repair inhibitor. Considering that endogenous source of mutation (ESM) constantly assaults genomic DNA and likely sensitizes human cancer cells to the inhibitor, we first analyzed the statistical relationship between the expression of individual genes and the mutations for KIRC. Among the candidates, EXOSC1 most notably promoted DNA damages and subsequent mutations via preferentially cleaving C site(s) in single-stranded DNA. Consistently, EXOSC1 was more *For correspondence: significantly correlated with C>A transversions in coding strands than these in template strands in [email protected] human KIRC. Notably, KIRC patients with high EXOSC1 showed a poor prognosis, and EXOSC1 (CS); sensitized human cancer cells to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. These results show that [email protected] (QY) EXOSC1 acts as an ESM in KIRC, and targeting EXOSC1 might be a potential therapeutic strategy. †These authors contributed equally to this work Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no DNA damages and subsequent mutations are central to development, progression, and treatment competing interests exist. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Regulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Expression and Cell Cycle Progression by an Endogenous Antisense RNA

Genes 2012, 3, 505-520; doi:10.3390/genes3030505 OPEN ACCESS genes ISSN 2073-4425 www.mdpi.com/journal/genes Article Regulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Expression and Cell Cycle Progression by an Endogenous Antisense RNA Mark Baguma-Nibasheka, Leigh Ann MacFarlane and Paul R. Murphy * Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, 5850 College Street, Halifax, NS B3H 4R2, Canada; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.B.-N.); [email protected] (L.A.M.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-902-494-1579; Fax: +1-902-494-2050. Received: 27 June 2012; in revised form: 31 July 2012 / Accepted: 15 August 2012 / Published: 16 August 2012 Abstract: Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) is a potent wide-spectrum mitogen whose overexpression is associated with immortalization and unregulated cell proliferation in many tumors. The FGF2 gene locus is bi-directionally transcribed to produce FGF2 P51$IURPWKH³VHQVH´VWUDQGDQGDcis-antisense RNA (NUDT6) from the NUDT6 gene RQWKH³DQWLVHQVH´VWUDQG7KH18'7JHQHHQFRGHVDQXGL[PRWLISURWHLQRIXQNQRZQ function, while its mRNA has been implicated in the post-transcriptional regulation of FGF2 expression. FGF2 and NUDT6 are co-expressed in rat C6 glioma cells, and ectopic overexpression of NUDT6 suppresses cellular FGF2 accumulation and cell cycle progression. However, the role of the endogenous antisense RNA in regulation of FGF2 is unclear. In the present study, we employed siRNA-mediated gene knockdown to examine the role of the endogenous NUDT6 RNA in regulation of FGF2 expression and cell cycle progression. Knockdown of either FGF2 or NUDT6 mRNA was accompanied by a significant (>3 fold) increase in the complementary partner RNA.