The Artpolitics of May Stevens' Work: Disrupting the Distribution of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

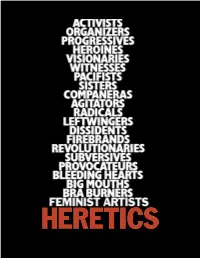

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

MAY STEVENS B. 1924 Boston, MA D. 2019 Santa Fe, NM

MAY STEVENS b. 1924 Boston, MA d. 2019 Santa Fe, NM Education 1988-89 Postdoctoral Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1960 MFA Equivalency, New York City Board of Education 1948 Art Students League, New York, NY 1948 Academie Julian, Paris, France 1946 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, MA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976-1981, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2017 Alice in the Garden, RYAN LEE, New York, NY Big Daddy Paper Doll, RLWindow, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2014 May Stevens: Fight the Power, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2013 May Stevens: Political Pop at ADAA, Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY 2012 May Stevens: The Big Daddy Series, National Academy of Design, New York, NY 2011 One Plus or Minus One, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2010 May Stevens: Crossing Time, I.D.E.A. Space at Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 2008 May Stevens: Paintings and Works on Paper, 1968-1975, Mary Ryan Gallery, NY 2007 ashes rock snow water: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Women, Words, and Water: Works on Paper by May Stevens, Rutgers University 2005 The Water Remembers: Paintings and Works on Paper from 1990- 2004, Springfield Museum of Art, Springfield, MO; traveled to the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, MN and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC 2005 New Works, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Deep River: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, CA 2000 -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976 - 1991 October 17 - December 21, 2019 Opening Reception: Thursday, October 17, 6-8Pm

May Stevens Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976 - 1991 October 17 - December 21, 2019 Opening Reception: Thursday, October 17, 6-8pm RYAN LEE is pleased to announce May Stevens: Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976–1991, an exhibition that illuminates Stevens’ long engagement with the political activist Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919). Over a period dating from the late seventies to the early nineties, Stevens (1924-2019), a celebrated artist, writer, teacher, feminist activist, and founding member of Heresies, produced over seventy works exploring the life and death of Luxemburg. The exhibition revisits a selection from this powerful body of work—presenting several works on paper for the first time—on the 100th anniversary of Luxemburg’s death. Luxemburg was a Polish-German Marxist philosopher, prolific writer, and activist whose legacy includes co-founding the German Communist Party. Stevens first became interested in Luxemburg in the late 1970s through her close friends Lucy Lippard and Alan Wallach, and she quickly grew fascinated by Luxemburg’s strength and intelligence. Over a period of nearly twenty years Stevens produced several series of works—some thirty collages, thirteen drawings, a handful of prints, and approximately fourteen paintings—that endeavor to untangle Luxemburg’s identity, accomplishments, and her murder at the hands of the German state. Stevens’ imagery draws on reproductions of Luxemburg taken from newspaper coverage of her assassination, and is often overlaid with quotations from Luxemburg’s own writing. Stevens’ first images of Luxemburg,Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (1976) and Untitled (Original Rosa/Alice Collage) (1976) were produced for the inaugural issue of the pioneering feminist journal Heresies in 1977 and will be on view in this exhibition. -

Full Bibliography

Harmony Hammond Full Bibliography PUBLICATIONS BY AND ABOUT HARMONY HAMMOND AND HER WORK 2019 Harmony Hammond: Material Witness, Five Decades of Art, Catalogue essay by Amy Smith- Stewart. Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and Gregory R. Miller & Co. (New York) Vitamin T: Threads & Textiles, 2019. Phaidon Press Limited (London) “Harmony Hammond”, interviewed by Tara Burk. Art After Stonewall: 1969 – 1989, ed. Jonathan Weinberg. Rizzoli Electa (New York) Queer Abstraction, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA. Catalogue essays by Jared Ledesma and David Getsy, About Face: Gender, Revolt & the New Queer Art, Wrightwood 659, Chicago, IL. Catalogue essay by Jonathan D. Katz “Artists and Creatives Reflect on How Stonewall Changed Art”, Julia Wolkoff. Artsy, June 14 “Queer Art, Gay Pride, and the Stonewall Riots –50 Years Later”,Sur Rodney (Sur). Artsy. June 3, “West By Southwest: Considering Landscape in Contemporary Art”, Shane Tolbert. The Magazine, June “Lucy Lippard”, Jenn Shapland. The Magazine, June “Queer Artists in Their Own Words: Savannah Knoop Is an Intimacy Hound”, Zachary Small. Hyperallergic, June 7 “Beyond Boston: 6 Summer Exhibits Around New England”. WBUR. The ARTery. June 4 “A Show About Stonewall’s Legacy Falters on Indecision”,Danilo Machado, Hyperallergic,June 6 “Critic’s Pick’s, Holland Cotter. The New York Times, May 30 “Material Witness: Five Decades of Art”, Ariella Wolens. SPIKE ART #59, Spring “Blood, Sweat and Piss: Art Is a Hard Job”, Osman Can Yerebakan. ELEPHANT, May 18 “Why So Many Artists Have Been Drawn to New Mexico”, Alexxa Gotthardt, Artsy, May 17 “Art After Stonewall, 1969 – 1989”, Jonathan Weinberg and Anna Conlan, The Archive, Spring “Playful furniture, Native Art, and hidden grottoes are a few of the highlights from this season’s top exhibitions”, AFAR, May 10 “’art after stonewall’ examines a crucial moment in lgbtq history”. -

The Heretics, from Prince Street to Galisteo | Adobeairstream

The Heretics, from Prince Street to Galisteo | AdobeAirstream http://adobeairstream.com/art/the-heretics-from-prince-street-to-... Home » Art » The Heretics, from Prince Street to Galisteo The Heretics, from Prince Street to Galisteo Written by Ellen Berkovitch // December 7, 2009 // Art, Film, Santa Fe // 2 Comments 2 of 12 11/4/11 4:18 PM The Heretics, from Prince Street to Galisteo | AdobeAirstream http://adobeairstream.com/art/the-heretics-from-prince-street-to-... Pat Steir Pat Steir was one. So were Ida Applebroog, Harmony Hammond, May Stevens, Carolee Schneeman, Cecilia Vicuna, Emma Amos, Joyce Kozloff, Mary Beth Edelson, Joan Braderman (who made the new documentary, The Heretics), Lucy Lippard, Elizabeth Murray. See for yourself. In a scene in the movie The Heretics (2009), painter Miriam Schapiro leans in to read aloud a block of Adrienne Rich text on one of her works, and opines that she might cry. But it wasnt the verse that Schapiro read, but this Rich line — a wild patience has taken me this far – that cries to be remembered in connection to the new Joan Braderman documentary film about the women who formed, created and recreated the journal Heresies (1977-92/New York City). They strove as they did so to perfect and redefine the relationship of words and images to experience, all of it distilled and communicated through womens work. Heresies was a printed journal that coalesced at the point of a movement whose only organizing force was the non-hierarchal female in self-discovery as an artist, writer, critic, and unabashed feminist. That these women had a lot to say goes without saying. -

May Stevens Alice in the Garden February 23 – April 8, 2017 Opening Reception: February 25, 4–6Pm

May Stevens Alice in the Garden February 23 – April 8, 2017 Opening reception: February 25, 4–6pm RYAN LEE is pleased to announce Alice in the Garden, an exhibition of monumental paintings by the pioneering feminist artist May Stevens. A celebrated activist committed to the civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements, Stevens has used painting to combat social injustice and to revise women’s history throughout her seventy-year career. Between 1983 and 1990, she produced several large-scale paintings on unstretched canvas depicting Alice Dick Stevens, her elderly mother, during the last years of her life. The five-panel painting Alice in the Garden (1988-89) is based on Stevens’s own photographs of Alice taken during visits to the nursing home in which she lived. The mural-like images confront the viewer with the massive figure of Alice—fleshy, fragile, and vulnerable. In her hands, Alice manipulates flowers—dandelions Stevens had playfully thrown at her during an afternoon visit. In the final painting of the cycle, Stevens, with her back to the viewer, pins a flower to her mother’s blouse. Stevens’s photos also serve as the source material for the previously un- exhibited A Life (1984), painted during Alice’s final years. These powerful images of Alice evolved from an earlier series of paintings, entitled Ordinary/ Extraordinary (1977-84), in which Stevens juxtaposed her biological mother with Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919), the Polish-German Marxist revolutionary leader whom she often called her “spiritual mother.” Studying the lives of these two very different women was essential to Stevens’s ongoing exploration of the range and diversity of women’s experiences, including the possibilities, limitations, and contradictions that often defined them. -

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’S Collaborative Art + Community

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’s Collaborative Art + Community BY CAREY LOVELACE We are developing the ability to work collectively and politically rather than privately and personally. From these will be built the values of the new society. —Roxanne Dunbar 1 “Female Liberation as the Basis for Social Liberation,” 1970 Cheri Gaulke (Feminist Art Workers member) has developed a theory of performance: “One plus one equals three.” —KMC Minns 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” 1979 3 “All for one and one for all” was the cheer of the Little Rascals (including token female Darla). Our Gang movies, with their ragtag children-heroes, were filmed during the Depression. This was an age of the collective spirit, fostering the idea that common folk banding together could defeat powerful interests. (Après moi, Walmart!) Front Range, Front Range Women Artists, Boulder , CO, 1984 (Jerry R. West, Model). Photo courtesy of Meridel Rubinstein. The artists and groups in Making It Together: Women’s Collaborative Art and Community come from the 1970s, another era believing in communal potential. This exhibition covers a period stretching 4 roughly from 1969 through 1985, and those featured here engaged in social action—inspiringly, 1 In Robin Morgan, Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: Vintage Books, 1970), 492. 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” Spinning Off, May 1979. 3 Echoing the Three Muskateers. 4 As points of historical reference: NOW was formed in 1966, the first radical Women’s Liberation groups emerged in 1967. The 1970s saw a range of breakthroughs: In 1971, the Supreme Court decision Roe v. -

TRB E-List 2

E-list #2 - ’21 Political Activist Peace Party Collection, Gay flyers, Women’s Protest flyers…and more. Copyright © 2012 Tomberg Rare Books, All rights reserved. My mailing address is: Tomberg Rare Books 11506 Claymont Circle Windermere, Fl 34786 203-223-5412 [email protected] www.tombergrarebooks.com unsubscribe from this list. Type to enter text 1. Peace Party Collection A huge and substantial collection of political ephemera from the People’s Party, an independent political party, third party founded in 1971 by a group of individuals, state and local political parties, including the Peace and Freedom Party, Commongood People's Party, Country People's Caucus, Human Rights Party, Liberty Union, New American Party, New Party (Arizona), and No Party (Wikipedia). The party fielded Dr. Spock for President in the 1972 campaign and Margaret Wright (with Spock as Vice- President) in the 1976 race. The group’s platform included the withdrawal of all American forces around the work, amnesty for war resisters, legalization of marijuana, an end to discrimination against women and gays, self-determination for oppressed groups, including statehood for the colonized people of Washington, DC (!), free medical care, and a minimum allowance for families. The group largely dissolved following their dismal showing in the 1976 election. The collection includes 8 1⁄2” x 11” flyers primarily issued by the People’s Party of Cook County, located outside of Chicago. The earliest flyer is from The New Party and proposes the formation of a “radical political alternative,” which we assume was an early iteration of the People’s Party. Dr. -

May Stevens: Mysteries, Politics, and Seas of Words on View Through August 1, 2021

SITE SANTA FE ANNOUNCES EXHIBITION EXTENSION SITElab14: May Stevens: Mysteries, Politics, and Seas of Words on view through August 1, 2021 May Stevens,The Canal, 1988. (c) May Stevens; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. For Immediate Release: June 2, 2021, Santa Fe, NM - SITE Santa Fe announces an extension of SITElab 14: May Stevens: Mysteries, Politics, and Seas of Words -- a survey of the career of internationally recognized painter May Stevens (1924-2019), curated by Brandee Caoba and Lucy R. Lippard. This exhibition has attracted thousands of visitors and has received great local and National press coverage. A catalogue will be published in conjunction with this exhibition that will include selected writings by May Stevens, and essays by Brandee Caoba and Lucy R. Lippard. Throughout her seventy-year career, Stevens made art to combat social injustice and amplify voices of women throughout history. She firmly believed that art must be used for social commentary not just personal expression. Her studio practice engaged with many social movements including Civil Rights, anti-Vietnam War, and Feminism. Stevens was a founding member of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, and an original Guerrilla Girl at the feminist group’s founding in 1985. May Stevens: Mysteries, Politics, and Seas of Words includes paintings from 1964 – 2008, a full collection of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, and screenings of The Heretics, a feature-length, documentary film written and directed by collective member, Joan Braderman. Stevens’ paintings comment on historical, political, and social conditions as well as the human condition, including poignant meditations on loss and grief. -

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Throughout its history, the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art has documented the role of women in the art world by collecting the papers and oral histories of prominent women artists, critics, and art historians along with the records of institutions that supported or disseminated their work. Highlights include the papers of Lucy Lippard and Linda Nochlin, the Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women in the Visual Arts Project, oral history interviews with the Guerilla Girls, the Woman’s Building records, and much more. You can explore the Archives’ research collections online at http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections. Among the more than 6,000 collections available at the Archives of American Art are the papers of Berenice Abbott Ita H. Aber Gertrude Abercrombie Pat Adams Virginia Admiral Lee Adler Leslie Judd Ahlander Adela Akers Grace Albee Anni Albers Neda Al-Hilali Mabel Alvarez American Association of University Women Edna Andrade Laura Andreson Vera Andrus Ruth Armer Florence Arquin Artists in Residence (A.I.R.) Gallery ArtTable, Inc. Mary Ascher Elise Asher Dore Ashton Dotty Attie Alice Baber Peggy Bacon Mildred Baker Dorothy Dehner Cecilia Beaux Gretchen Bender Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne Hermine Benhaim Vera Berdich Rosalie Berkowitz collection of photographs Avis Berman Betty Cunningham Gallery Betty Parsons Gallery Ilse Martha Bischoff Isabel Bishop Kathleen Blackshear and Ethel Spears Harriet Blackstone Nell Blaine Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake Lucienne Bloch Dorr Bothwell Nancy Douglas Bowditch and Brush Family Ruth Bowman E. Boyd Braunstein Quay Gallery Adelyn Dohme Breeskin Anna Richards Brewster Romaine Brooks Norma Broude and Mary Garrard Joan Brown Louise Bruner Bernarda Bryson Shahn Eleanor H. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You willa find good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.