V8f SJQ. Ihci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

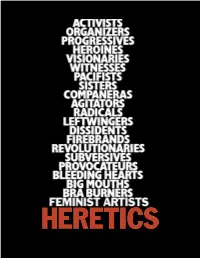

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

IN DEEP WATER for Filing

IN DEEP WATER: THE OCEANIC IN THE BRITISH IMAGINARY, 1666-1805 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colin Dewey May 2011 © 2011 Colin Dewey IN DEEP WATER: THE OCEANIC IN THE BRITISH IMAGINARY, 1666-1805 Colin Dewey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This study argues that the ocean has determined the constitution of British identity – both the collective identity of an imperial nation and the private identity of individual imagination. Romantic-era literary works, maritime and seascape paintings, engravings and popular texts reveal a problematic national and individual engagement with the sea. Historians have long understood the importance of the sea to the development of the British empire, yet literary critics have been slow to take up the study of oceanic discourse, especially in relation to the Romantic period. Scholars have historicized “Nature” in literature and visual art as the product of an aesthetic ideology of landscape and terrestrial phenomena; my intervention is to consider ocean-space and the sea voyage as topoi that actively disrupt a corresponding aesthetic of the sea, rendering instead an ideologically unstable oceanic imaginary. More than the “other” or opposite of land, in this reading the sea becomes an antagonist of Nature. When Romantic poets looked to the ocean, the tracks of countless voyages had already inscribed an historic national space of commerce, power and violence. However necessary, the threat presented by a population of seafarers whose loyalty was historically ambiguous mapped onto both the material and moral landscape of Britain. -

MAY STEVENS B. 1924 Boston, MA D. 2019 Santa Fe, NM

MAY STEVENS b. 1924 Boston, MA d. 2019 Santa Fe, NM Education 1988-89 Postdoctoral Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1960 MFA Equivalency, New York City Board of Education 1948 Art Students League, New York, NY 1948 Academie Julian, Paris, France 1946 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, MA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976-1981, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2017 Alice in the Garden, RYAN LEE, New York, NY Big Daddy Paper Doll, RLWindow, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2014 May Stevens: Fight the Power, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2013 May Stevens: Political Pop at ADAA, Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY 2012 May Stevens: The Big Daddy Series, National Academy of Design, New York, NY 2011 One Plus or Minus One, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2010 May Stevens: Crossing Time, I.D.E.A. Space at Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 2008 May Stevens: Paintings and Works on Paper, 1968-1975, Mary Ryan Gallery, NY 2007 ashes rock snow water: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Women, Words, and Water: Works on Paper by May Stevens, Rutgers University 2005 The Water Remembers: Paintings and Works on Paper from 1990- 2004, Springfield Museum of Art, Springfield, MO; traveled to the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, MN and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC 2005 New Works, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Deep River: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, CA 2000 -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

Questions of Feminism

AYISHAABRAHAM (Question 2) I wonder if it is possible to demarcatethe 1960s and '80s in termsof clearly distinguishablecategories of "grassroots" and "theory."Would our understanding be where it is without the pathbreaking grass roots-theoreticalwork done by activists/artists/theoristswho have traditionallybelonged to marginalized communities? The issue of formationsand expressionsof subjectivityin and throughart is crucialhere. In the United States,with the help of the popular pressand media, politics tends to be reduced to essentializedand deterministicnotions of race, ethnicity,femininity, otherness, etc. This convenientlycloaks all the othercategories thathave not been legitimizedwithin the classicself/other binary debates. In a recentarticle entitled "Interior Colonies: Franz Fanon and the Politics of Identification,"Diana Fuss locates psychoanalyticdiscourse and the politicsof identificationwithin colonial historyand otherhistorical genealogies: It therefore becomes necessary for the colonizer to subject the colonial other to a double command: be like me, don't be like me; be mimeticallyidentical, be totallyother. The colonial other is situated somewherebetween differenceand similitude,at the vanishingpoint of subjectivity.' While it is stillhard forartists from marginalized communities to negotiatetheir identities within the context of the art world, there are manywho have used strategies such as autobiography to explore a history that has never been interrogatedbefore. The problem only arises when termssuch as "the body," "autobiography,"etc., are taken out of their historical contexts and thrown around like disembodiedand rarefiedconcepts. I findmyself becoming more conscious of the extentto whichmy work has to be informedboth by theoreticalanalyses and directpractical engagement with complex issues of subjectivity,identity, etc. I feel the need to look at the specifics of these issues.It is the politicsof processthat interests me. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

The Artpolitics of May Stevens' Work: Disrupting the Distribution of The

The Artpolitics of May Stevens’ work: disrupting the distribution of the sensible Abstract: In this paper I look into the life and art of May Stevens, an American working class woman, feminist and committed political activist. I am particularly interested in how Steven’s artwork is inextricably interwoven with her politics, constituting, as I will argue an assemblage of artpolitics. The discussion draws on Jacques Rancière’s analyses of the politics of aesthetics and particularly his notion of ‘the distribution of the sensible’. What I argue is that although Rancière’s approach to the politics of aesthetics illuminates an understanding and appreciation of Stevens’ art, his idea about the redistribution of the sensible is problematic. It is here that the notion of artpolitics as an assemblage opens up possibilities for a critical project that goes beyond the limitations of Rancière’s proposition. Key words: aesthetics, artpolitics, distribution of the sensible, narratives, women artists There’s an expression that I’ve used a lot, a quotation from Butler Yeats, who said that you have to choose between ‘perfection of the life, or of the work.’ I refuse to do that. I will not choose. (Hills, 2005: 11) In a series of in-depth conversations with Patricia Hill (2005), American artist May Stevens (1924-) rejects Yates’ suggestion above about the incompatibility of life and art and insists on keeping them together. It is this agonistic project of fusing life into art and art into life that I will discuss in this paper, focusing on a working class artist, feminist and politically committed activist, who erupted as an event in my overall project of writing a genealogy of the female self in art. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture. -

NINA YANKOWITZ , Media Artist , N.Y.C

NINA YANKOWITZ , media artist , N.Y.C. www.nyartprojects.com SELETED MUSUEM INSTALLATIONS 2009 The Third Woman interactive film collaboration,Kusthalle Vienna 2009 Crossings Interactive Installation Thess. Biennale Greece Projections, CD Yankowitz&Holden, Dia Center for Book Arts, NYC 2009 Katowice Academy of Art Museum, Poland TheThird Woman Video Tease, Karsplatz Ubahn, project space Vienna 2005 Guild Hall Art Museum, East Hampton, NY Voices of The Eye & Scenario Sounds, distributed by Printed Matter N.Y. 1990 Katonah Museum of Art, The Technological Muse Collaborative Global New Media Team/Public Art Installation Projects, 2008- 2009 1996 The Bass Museum, Miami, Florida PUBLIC PROJECTS 1987 Snug Harbor Museum, Staten Island, N.Yl 1985 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA Tile project Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad, India 2008 1981 Maryland Museum of Fine Arts, Baltimore, MD 1973 Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, Biennia 1973 Brockton Museum, Boston, MA 1972 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. Works on paper 1972 Kunsthaus, Hamburg, Germany, American Women Artists 1972 The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey 1972 Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art 1972 The Art Institute of Chicago, "American Artists Today" 1972 Suffolk Museum, Stonybrook, NY 1971 Akron Museum of Art, Akron, OH 1970 Museum of Modern Art, NY 1970 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. "Highlights" 1970 Trinity College Museum, Hartford, Conn. ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2005 Kiosk.Edu. Guild Hall Museum, The Garden, E. Hampton, New York 1998 Art In General, NYC. "Scale -

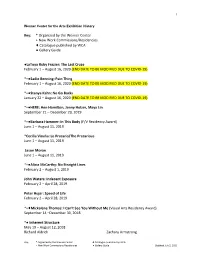

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Surface Work

Surface Work Private View 6 – 8pm, Wednesday 11 April 2018 11 April – 19 May 2018 Victoria Miro, Wharf Road, London N1 7RW 11 April – 16 June 2018 Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE Image: Adriana Varejão, Azulejão (Moon), 2018 Oil and plaster on canvas, 180 x 180cm. Photograph: Jaime Acioli © the artist, courtesy Victoria Miro, London / Venice Taking place across Victoria Miro’s London galleries, this international, cross-generational exhibition is a celebration of women artists who have shaped and transformed, and continue to influence and expand, the language and definition of abstract painting. More than 50 artists from North and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia are represented. The earliest work, an ink on paper work by the Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova, was completed in 1918. The most recent, by contemporary artists including Adriana Varejão, Svenja Deininger and Elizabeth Neel, have been made especially for the exhibition. A number of the artists in the exhibition were born in the final decades of the nineteenth century, while the youngest, Beirut-based Dala Nasser, was born in 1990. Work from every decade between 1918 and 2018 is featured. Surface Work takes its title from a quote by the Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell, who said: ‘Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work.’ The exhibition reflects the ways in which women have been at the heart of abstract art’s development over the past century, from those who propelled the language of abstraction forward, often with little recognition, to those who have built upon the legacy of earlier generations, using abstraction to open new paths to optical, emotional, cultural, and even political expression.