Michelle Stuart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

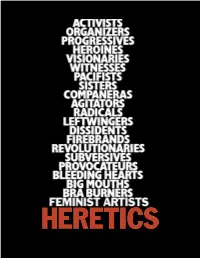

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

Weekly Schedule

ARTH 787: Seminar in Contemporary Art Feminist and Queer Art History, 1971-present Spring 2007 Professor Richard Meyer ([email protected]) Mondays, 2-4:50 p.m. Dept. of Art History, University of Pennsylvania Jaffe 201 Course Description and Requirements This seminar traces the development of a critical literature in feminist and gay/lesbian art history. Beginning with some foundational texts of the 1970s (Linda Nochlin’s "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” James Saslow’s "Closets in the Museum: Homophobia and Art History"), we will examine how art historians, artists, critics, and curators have addressed issues of gender and sexuality over the course of the last three decades. The seminar approaches feminist and queer art history as distinct, if sometimes allied, fields of inquiry. Students will be asked to attend closely to the historical specificity of the texts and critical debates at issue in each case. Students are expected to complete all required reading prior to seminar meetings and to discuss the texts and critical issues at hand during each session. On a rotating basis, each student will prepare a 2-page response to an assigned text which will then be used to initiate discussion in seminar. Toward the end of the semester, students will deliver a 15-minute presentation on their seminar research to date. In consultation with both the professor and the other seminar members, each student will develop his or her oral presentation into a final paper of approximately 20 - 25 pages. Required Texts: For purchase at Penn Book Center: 1. Norma Broude and Mary Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact (New York: Harry N. -

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City Education Depuis 1788 Brighton School of Art, Sussex, England Freymond-Guth Fine Arts Riehenstrasse 90 B CH 4058 Basel T +41 (0)61 501 9020 offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Selected Exhibitions & Projects („s“ = Solo Exhibition) 2017 Whitney Museum for American Art, New York, USA Mostyn, Llundadno, Wales, UK (s) Reflections on the surface, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Basel, CH 2016 MUMOK Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna, AUT Museum Brandhorst, Munich, DE 2015 The Crystal Palace, Sylvia Sleigh I Yorgos Sapountzis, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2014 Shit and Die, Palazzo Cavour, cur. Maurizio Cattelan, Turin, IT Praxis, Wayne State University‘s Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Detroit, USA Frieze New York, with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, New York, NY Le salon particulier, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) 2013 / 14 Sylvia Sleigh, CAPC Musée d‘Art Contemporain de Bordeaux Bordeaux, FR (s) Tate Liverpool, UK, (s) CAC Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporanea Sevilla, ES (s) 2013 The Weak Sex / Das schwache Geschlecht, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, CH 2012 Sylvia Sleigh, cur. Mats Stjernstedt, Giovanni Carmine, Alexis Vaillant in collaboration w Francesco Manacorda and Katya Garcia-Anton, Kunstnernes Hus Oslo, NOR (s) Kunst Halle St. Gallen, CH (s) Physical! Physical!, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2011 Art 42 Basel: Art Feature (with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich), Basel CH (s) The Secret Garden, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Anyone can do anything? genius without talents, cur. Ann Demeester, De Appel, Amsterdam, NL 2010 Working at home, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) The Comfort of Strangers, curated by Cecila Alemani, PS1 Contemporary Art Cen ter, New York, NY 2009 I-20 Gallery, New York, NY (s) Wiser Than God, curated by Adrian Dannatt, BLT Gallery, New York, NY The Three Fs: form, fashion, fate, curated by Megan Sullivan, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Ingres and the Moderns, Musée national des Beaux-Arts, Quebec. -

Not for the Uncommitted: the Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 By

Not for the Uncommitted: The Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 By Emily D. Markert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Curatorial Practice California College of the Arts April 22, 2021 Not for the Uncommitted: The Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 Emily Markert California College of the Arts 2021 From 1969 through the early 1980s, hundreds of working artists gathered on Manhattan’s Lower East Side every Friday at meetings of the Alliance of Figurative Artists. The art historical canon overlooks figurative art from this period by focusing on a linear progression of modernism towards medium specificity. However, figurative painters persisted on the periphery of the New York art world. The size and scope of the Alliance and the interests of the artists involved expose the popular narrative of these generative decades in American art history to be a partial one promulgated by a few powerful art critics and curators. This exploration of the early years of the Alliance is divided into three parts: examining the group’s structure and the varied yet cohesive interests of eleven key artists; situating the Alliance within the contemporary New York arts landscape; and highlighting the contributions women artists made to the Alliance. Keywords: Post-war American art, figurative painting, realism, artist-run galleries, exhibitions history, feminist art history, second-wave feminism Acknowledgments and Dedication I would foremost like to thank the members of my thesis committee for their support and guidance. I am grateful to Jez Flores-García, my thesis advisor, for encouraging rigorous and thoughtful research and for always making time to discuss my ideas and questions. -

NINA YANKOWITZ , Media Artist , N.Y.C

NINA YANKOWITZ , media artist , N.Y.C. www.nyartprojects.com SELETED MUSUEM INSTALLATIONS 2009 The Third Woman interactive film collaboration,Kusthalle Vienna 2009 Crossings Interactive Installation Thess. Biennale Greece Projections, CD Yankowitz&Holden, Dia Center for Book Arts, NYC 2009 Katowice Academy of Art Museum, Poland TheThird Woman Video Tease, Karsplatz Ubahn, project space Vienna 2005 Guild Hall Art Museum, East Hampton, NY Voices of The Eye & Scenario Sounds, distributed by Printed Matter N.Y. 1990 Katonah Museum of Art, The Technological Muse Collaborative Global New Media Team/Public Art Installation Projects, 2008- 2009 1996 The Bass Museum, Miami, Florida PUBLIC PROJECTS 1987 Snug Harbor Museum, Staten Island, N.Yl 1985 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA Tile project Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad, India 2008 1981 Maryland Museum of Fine Arts, Baltimore, MD 1973 Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, Biennia 1973 Brockton Museum, Boston, MA 1972 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. Works on paper 1972 Kunsthaus, Hamburg, Germany, American Women Artists 1972 The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey 1972 Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art 1972 The Art Institute of Chicago, "American Artists Today" 1972 Suffolk Museum, Stonybrook, NY 1971 Akron Museum of Art, Akron, OH 1970 Museum of Modern Art, NY 1970 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. "Highlights" 1970 Trinity College Museum, Hartford, Conn. ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2005 Kiosk.Edu. Guild Hall Museum, The Garden, E. Hampton, New York 1998 Art In General, NYC. "Scale -

1 the Embodied Artefact: a Nomadic Approach to Gendered Sites Of

The Embodied Artefact: A Nomadic Approach to Gendered Sites of Reverence through an Interdisciplinary Art Practice Author Rochester, Emma Christina Lucia Published 2017 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art. DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/166 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367914 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Embodied Artefact: A Nomadic Approach to Gendered Sites of Reverence through an Interdisciplinary Art Practice Emma Christina Lucia Rochester BA (Hons) BFA (Hons) Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2017 1 2 Abstract This doctoral project, “The Embodied Artefact: A Nomadic Approach to Gendered Sites of Reverence through an Interdisciplinary Art Practice”, moves beyond normative understandings of pilgrimage, God, and artistic scholarly research. Using a contemporary art lens, I travelled in a long durational performance to a multitude of international pilgrimage sites where God-as-Woman is, or has previously been, revered and respected. By moving towards and experiencing not just one destination but many, I have challenged the traditional paradigm of pilgrimage. In doing so, I have undergone a meta-experience whereby visitations to these psycho-spiritual terrains came together as a composite of embodied experiences. This blurring of boundaries seeks to go beyond the particularities of one newly revised gendered site of reverence to consider a process of pilgrimage that moves into and becomes nomadism, thereby developing significant new understandings across the fields of contemporary art practice and pilgrimage studies. -

Copyrighted Material

Contents Preface x Acknowledgements and Sources xii Introduction: Feminism–Art–Theory: Towards a (Political) Historiography 1 1 Overviews 8 Introduction 8 1.1 Gender in/of Culture 12 • Valerie Solanas, ‘Scum Manifesto’ (1968) 12 • Shulamith Firestone, ‘(Male) Culture’ (1970) 13 • Sherry B. Ortner, ‘Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?’ (1972) 17 • Carolee Schneemann, ‘From Tape no. 2 for Kitch’s Last Meal’ (1973) 26 1.2 Curating Feminisms 28 • Cornelia Butler, ‘Art and Feminism: An Ideology of Shifting Criteria’ (2007) 28 • Xabier Arakistain, ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: 86 Steps in 45 Years of Art and Feminism’ (2007) 33 • Mirjam Westen,COPYRIGHTED ‘rebelle: Introduction’ (2009) MATERIAL 35 2 Activism and Institutions 44 Introduction 44 2.1 Challenging Patriarchal Structures 51 • Women’s Ad Hoc Committee/Women Artists in Revolution/ WSABAL, ‘To the Viewing Public for the 1970 Whitney Annual Exhibition’ (1970) 51 • Monica Sjöö, ‘Art is a Revolutionary Act’ (1980) 52 • Guerrilla Girls, ‘The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist’ (1988) 54 0002230316.indd 5 12/22/2014 9:20:11 PM vi Contents • Mary Beth Edelson, ‘Male Grazing: An Open Letter to Thomas McEvilley’ (1989) 54 • Lubaina Himid, ‘In the Woodpile: Black Women Artists and the Modern Woman’ (1990) 60 • Jerry Saltz, ‘Where the Girls Aren’t’ (2006) 62 • East London Fawcett, ‘The Great East London Art Audit’ (2013) 64 2.2 Towards Feminist Structures 66 • WEB (West–East Coast Bag), ‘Consciousness‐Raising Rules’ (1972) 66 • Women’s Workshop, ‘A Brief History of the Women’s Workshop of the -

An Feminist Intervention 1

Total Art Journal • Volume 1. No. 1 • Summer 2011 POSTHUMAN PERFORMANCE An Feminist Intervention 1 LUCIAN GOMOLL Narcissister posing for IN*TANDEM, 2010. Image Credit: Gabriel Magdaleno/IN*TANDEM magazine Man will be erased like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea. —Michel Foucault, 1966 We have never been human. —Donna Haraway, 2006 1 I would like to dedicate this essay to the participants of my senior seminar “Women Artists, Self-Representations” taught during multiple terms at UC Santa Cruz, particularly my teaching assistant Lulu Meza, as well as students Christina Dinkel, Abby Law- ton and Allison Green. I am grateful to Natalie Loveless and Lissette Olivares for their critical feedback on early drafts of this article. I am also indebted to Donna Haraway and Jennifer González for their mentorship pertaining to the specific issues I explore here. Total Art Journal • Volume 1 No. 1 • Summer 2011 • http://www.totalartjournal.com In spring 2010, New York’s Museum of Modern Art hosted a popular and controversial retrospective of Marina Abramović’s oeuvre entitled The Artist is Present. Abramović herself participated in one seated per- formance at the exhibition and models were hired to play other roles she had become famous for. The retrospective included “Imponderabilia,” in which an unclothed man and woman stand in a doorway. For the first staging in 1977, Abramović and Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen) stood at the show’s entrance, in such close proximity that they forced most visitors to enter sideways and touch them both. Part of the work’s purpose was to see how the audience would respond to the gendered naked bodies.2 Audience squirming and forced decision-making were crucial elements of the piece, and are part of why it became so notorious. -

Miriam Schapiro, 91, a Feminist Artist Who Harnessed Craft and Pattern, Dies by William Grimes June 24, 2015

Miriam Schapiro, 91, a Feminist Artist Who Harnessed Craft and Pattern, Dies By William Grimes June 24, 2015 Miriam Schapiro, a pioneering feminist artist who, with Judy Chicago, created the landmark installation Womanhouse in Los Angeles in the early 1970s and later in that decade helped found the Pattern and Decoration movement, died on Saturday in Hampton Bays, N.Y. She was 91. Her death was confirmed by Judith K. Brodsky, the executor of her estate. Ms. Schapiro, who broke through as a second-generation Abstract Expressionist in the late 1950s, embraced feminism in the early 1970s and made it the foundation of her work and career. From that point, she dedicated herself to redefining the role of women in the arts and elevating the status of pattern, craft and the anonymous handiwork of women in the domestic sphere. “Mimi came to feminism later than most of us, in early middle age,” said Joyce Kozloff, one of Ms. Schapiro’s allies in the Pattern and Decoration movement. “It shook her world, transformed her into a radical thinker. She was a vocal, outspoken presence — a force.” In 1971, at the newly created California Institute of the Arts, she and Ms. Chicago founded the Feminist Art Program. (An earlier version of the program had been established at Fresno State College the year before.) It quickly became an important center for formulating and disseminating a new understanding of art based on women’s history and social experience. That year they enlisted 21 students and several local artists to create Womanhouse, taking over a decaying Hollywood mansion that made an effective set for dramatizing the American home as a prison for women and their dreams. -

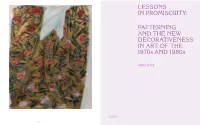

Lessons in Promiscuity

LESSONS IN PROMISCUITY: PATTERNING AND THE NEW DECORATIVENESS IN ART OF THE 1970s A ND 1980s ANNA KATZ Robert Zakanitch Dragon Fire, 1983 16 In 1975 in New York a group of artists gathered in the Warren Street loft of Robert Zakanitch to discuss a shared tendency that had emerged in their work in the preceding several years. Joyce Kozloff in her colorful paintings was combining patterns gleaned from architectural ornamentation, pottery, and textiles observed in Mexico, Morocco, Turkey, and Spain (fig. 1); Tony Robbin was using a modi- fied spray gun and patterned stencils to create spatially complex grids in lyric colors (pp. 122–25); Zakanitch was making paintings of massive, luscious blossoms in repeated patterns that evoked wallpaper and linoleum rugs (fig. 2); and Miriam Schapiro was collag- ing found bits of lace and other domestic fabrics associated with women’s lives in boisterous compositions (fig. 3). Joining them was Amy Goldin, an art critic with a strong interest in Islamic art, who had identified an “oddly persistent interest in pattern” in the 1 1 Amy Goldin, “The ‘New’ Whitney 1975 Whitney Biennial. Biennial: Pattern Emerging?,” Art in America, May/June 1975, 72–73. It is tempting to imagine that they gathered in secret, huddling together to confess their shared trespass, their violation of one of the strongest prohibitions of modern art: the decorative. But in truth their art was exuberant, and so were they, giddy with the thrill of destabilizing entrenched hierarchies, and the possibilities that unleashed. They identified -

Just Desserts"

Syracuse University Art Galleries • environment Syracuse University Art Galleries 1 ....... ' ........... 1 Women's Hall of Seneca Falls, NY May la-September la, 1981 Reception May 10,1-4 P.M. Joe & Emily Lowe Art Gallery Syracuse University September 27-November I, 1981 Reception September 27, 3-5 P.M. In the last ten year"s, a body of work by women has The main way that domestc :. n,r.o" re,"'; which contains matenals, or processes or in the still life, a form that can be personai, intimate. and associated with the domestic environment This political. Women have been redefining the tr-ad!tional still life in a the visual reflection of an examination of women's roles and number Instead of the classical arrangement of fr"uit and wne ences in this culture that has been with,n the fem:nist bottle (usually in a we al-e presented wth the movement. Until very recently these have been absent of what surrounds women in their daily lives-sinks full dishes, from mainstream art. In the past creative work that was done in the unmade beds, to be used or' food cooked home (and which was therefore women) was or and put up irl wrapped from the grocery put down as "craft". Since women and were not store. Sometimes neatly put away Oil considered important. any work that was of the home, the tdke over, as if to where "women's wor"k" was done, was consider"ed a woman's work is never fill the canvas as the or minor.