1 the Embodied Artefact: a Nomadic Approach to Gendered Sites Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City Education Depuis 1788 Brighton School of Art, Sussex, England Freymond-Guth Fine Arts Riehenstrasse 90 B CH 4058 Basel T +41 (0)61 501 9020 offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Selected Exhibitions & Projects („s“ = Solo Exhibition) 2017 Whitney Museum for American Art, New York, USA Mostyn, Llundadno, Wales, UK (s) Reflections on the surface, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Basel, CH 2016 MUMOK Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna, AUT Museum Brandhorst, Munich, DE 2015 The Crystal Palace, Sylvia Sleigh I Yorgos Sapountzis, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2014 Shit and Die, Palazzo Cavour, cur. Maurizio Cattelan, Turin, IT Praxis, Wayne State University‘s Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Detroit, USA Frieze New York, with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, New York, NY Le salon particulier, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) 2013 / 14 Sylvia Sleigh, CAPC Musée d‘Art Contemporain de Bordeaux Bordeaux, FR (s) Tate Liverpool, UK, (s) CAC Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporanea Sevilla, ES (s) 2013 The Weak Sex / Das schwache Geschlecht, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, CH 2012 Sylvia Sleigh, cur. Mats Stjernstedt, Giovanni Carmine, Alexis Vaillant in collaboration w Francesco Manacorda and Katya Garcia-Anton, Kunstnernes Hus Oslo, NOR (s) Kunst Halle St. Gallen, CH (s) Physical! Physical!, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2011 Art 42 Basel: Art Feature (with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich), Basel CH (s) The Secret Garden, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Anyone can do anything? genius without talents, cur. Ann Demeester, De Appel, Amsterdam, NL 2010 Working at home, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) The Comfort of Strangers, curated by Cecila Alemani, PS1 Contemporary Art Cen ter, New York, NY 2009 I-20 Gallery, New York, NY (s) Wiser Than God, curated by Adrian Dannatt, BLT Gallery, New York, NY The Three Fs: form, fashion, fate, curated by Megan Sullivan, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Ingres and the Moderns, Musée national des Beaux-Arts, Quebec. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

Michelle Stuart

Vol. 1 No. 4 r f l/IIIC 4i# U i I Spring-Summer 1977 WHY HAVE THERE BEEN NO GREAT WOMEN ARCHITECTS? As demonstrated by the recent show ; 1 L l at the Brooklyn Museum, the plight of women in this field \ j m | may be worse than that of women in the other visual arts by Elena Borstein..........................................................................p ag e 4 •if p r » l MICHELLE STUART: Atavism, Geomythology and Zen I d t i t k i ' j Stuart’s own writings, plus other revelations ' r : about the artist and her work by Robert H obbs ................................................................ p a g e 6 WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART Report from the President Women Architects by Judith Brodsky.................... .page 10 ON PAULA MODERSOHN-BECKER, GERMAN PAINTER Thoughts on her role as a woman versus her needs as an artist by Heidi Blocher.............................................................. .pa g e 13 NOTES ON GEORGIA O’KEEFFE’S IMAGERY Interpretation of her flower paintings need not remain solely in the realm of the sexual by Lawrence Al lo w a y ..............................................................p age 18 CALIFORNIA REVIEWS byPeterFrank ...........................................................................p a g e 23 GALLERY REVIEWS p ag e 24 REPORTS Queens College Library Program, Michelle Stuart Women's Art Symposium, Women Artists of the Northwest. .page34 Cover: Julia Morgan, San Simeon, San Luis Obispo, California, 1920-37. The Architectural League of New York. WOMANARTMAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P.O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station, New York, N.Y. -

CHANGING the EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING the EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP in the VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents

CHANGING THE EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING THE EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents 6 Acknowledgments 7 Preface Linda Nochlin This publication is a project of the New York Communications Committee. 8 Statement Lila Harnett Copyright ©2005 by ArtTable, Inc. 9 Statement All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted Diane B. Frankel by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. 11 Setting the Stage Published by ArtTable, Inc. Judith K. Brodsky Barbara Cavaliere, Managing Editor Renée Skuba, Designer Paul J. Weinstein Quality Printing, Inc., NY, Printer 29 “Those Fantastic Visionaries” Eleanor Munro ArtTable, Inc. 37 Highlights: 1980–2005 270 Lafayette Street, Suite 608 New York, NY 10012 Tel: (212) 343-1430 [email protected] www.arttable.org 94 Selection of Books HE WOMEN OF ARTTABLE ARE CELEBRATING a joyous twenty-fifth anniversary Acknowledgments Preface together. Together, the members can look back on years of consistent progress HE INITIAL IMPETUS FOR THIS BOOK was ArtTable’s 25th Anniversary. The approaching milestone set T and achievement, gained through the cooperative efforts of all of them. The us to thinking about the organization’s history. Was there a story to tell beyond the mere fact of organization started with twelve members in 1980, after the Women’s Art Movement had Tsustaining a quarter of a century, a story beyond survival and self-congratulation? As we rifled already achieved certain successes, mainly in the realm of women artists, who were through old files and forgotten photographs, recalling the organization’s twenty-five years of professional showing more widely and effectively, and in that of feminist art historians, who had networking and the remarkable women involved in it, a larger picture emerged. -

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012 Jan 23)

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012_Jan_23) GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011–January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design Introduction “Doin’ It in Public” documents a radical and fruitful period of art made by women at the Woman’s Building—a place described by Sondra Hale as “the first independent feminist cultural institution in the world.” The exhibition, two‐volume publication, website, video herstories, timeline, bibliography, performances, and educational programming offer accounts of the collaborations, performances, and courses conceived and conducted at the Woman’s Building (WB) and reflect on the nonprofit organization’s significant impact on the development of art and literature in Los Angeles between 1973 and 1991. The WB was founded in downtown Los Angeles in fall 1973 by artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a public center for women’s culture with art galleries, classrooms, workshops, performance spaces, bookstore, travel agency, and café. At the time, it was described in promotional materials as “a special place where women can learn, work, explore, develop their own point of view and share it with everyone. Women of every age, race, economic group, lifestyle and sexuality are welcome. Women are invited to express themselves freely both verbally and visually to other women and the whole community.” When we first conceived of “Doin’ It in Public,” we wanted to incorporate the principles of feminist art education into our process. -

Every Ocean Hughes Thursday, February 6, 2020, 2:00 PM Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College Annandale on Hudson, N.Y

Speakers Series : Every Ocean Hughes Thursday, February 6, 2020, 2:00 PM Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College Annandale on Hudson, N.Y. 00:00:01:00 LAUREN CORNELL: Hi. I’m Lauren Cornell. I’m the director of the graduate program, and chief curator here at CCS Bard. Thank you so much for being here. It’s my pleasure to introduce Every Ocean Hughes, an artist and writer who’s been based in Stockholm since 2014, but is in the Northeast of the US now because she is currently a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard. So in the past decade, Every’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Kunsthalle Lissabon; Secession, in Vienna; Participant Inc.; Art in General; and the Berkeley Art Museum. She’s received commissions for new performance and installation from Tate Modern, The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, and The Kitchen. And her work has been featured in multiple biennials, including those—this is not the entire list—in Gwangju; Sydney; The Whitney, in New York City; Manifesta, in Spain; and she and I worked together at the New Museum Triennial in 2009. 00:01:03:25 So in the aughts, before moving to Stockholm, Every lived in New York City. Reflecting on that time in a conversation with the curator Xabier Arakistan, Every wrote about how in her early years, she had had one foot in a theoretically- and politically-engaged practice via the Whitney Independent Study Program, and another foot in the queer pop punk scene. In the same conversation, Every said that after the ISP, she took a long trip alone and then came back to New York and co-founded LTTR with artists K8 Hardy and Ginger Brooks Takahashi, implying that she brought these two fields together in this project. -

Download Issue (PDF)

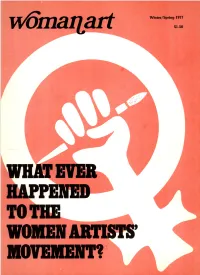

Vol. 1 No. 3 r r l S J L f J C L f f C t J I Winter/Spring 1977 AT LONG LAST —An historical view of art made by women by Miriam Schapiro page 4 DIALOGUES WITH NANCY SPERO by Carol De Pasquale page 8 THE SISTER CHAPEL —A traveling homage to heroines by Gloria Feman Orenstein page 12 'Women Artists: 1550— 1950’ ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI — Her life in art, part II by Barbara Cavaliere page 22 THE WOMEN ARTISTS’ MOVEMENT —An Assessment Interviews with June Blum, Mary Ann Gillies, Lucy Lippard, Pat Mainardi, Linda Nochlin, Ce Roser, Miriam Schapiro, Jackie Skiles, Nancy Spero, and Michelle Stuart page 26 THE VIEW FROM SONOMA by Lawrence Alloway page 40 The Sister Chapel GALLERY REVIEWS page 41 REPORTS ‘Realists Choose Realists’ and the Douglass College Library Program page 51 WOMANART MAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P. O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station, New York, N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 for one year. All opinions expressed are those o f the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those o f the editors. This publication is on file with the International Women’s History Archive, Special Collections Library, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60201. Permission to reprint must be secured in writing from the publishers. Copyright © Artemisia Gentileschi- Fame' Womanart Enterprises, 1977. A ll rights reserved. AT LONG LAST AN HISTORICAL VIEW OF ART MADE BY WOMEN by Miriam Schapiro Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Birds and Fruit, ca. -

Diana Kurz's Holocaust Paintings: a Chance Encounter That Was No Accident Author(S): Evelyn Torton Beck Source: Feminist Studies, Vol

Diana Kurz's Holocaust Paintings: A Chance Encounter That Was No Accident Author(s): Evelyn Torton Beck Source: Feminist Studies, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 80-100 Published by: Feminist Studies, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40607932 Accessed: 28-12-2017 18:43 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40607932?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Feminist Studies, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Feminist Studies This content downloaded from 129.2.19.102 on Thu, 28 Dec 2017 18:43:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Art Essay Diana Kurz9 s Holocaust Paintings: A Chance Encounter That Was No Accident Evelyn Torton Beck The odds that I would meet Diana Kurz at the 2006 New York gather- ing of Veteran Feminists of America were slim. Although we were both included in "the book," we did not know each other's work. But when, on a rainy October afternoon, hundreds of women gathered to celebrate the publication of Barbara Love's encyclopedic volume, Feminists Who Changed America, 1963-1975} some force of chance had us sitting a row apart. -

September 21—January 27, 2013 This Book Was Published on the Occasion of the Exhibition WOMEN

WOMEN ARTISTS II September 21—January 27, 2013 This book was published on the occasion of the exhibition WOMEN Women Artists of KMA II Kennedy Museum of Art, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio September 21—January 27, 2013 ARTISTS II September 21—January 27, 2013 Kennedy Museum of Art Lin Hall, Ohio University Athens, Ohio 45701 tel: 740.593.1304 web: www.ohio.edu/museum Design: Paula Welling Printing: Ohio University Printing Resources TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by Dr. Jennie Klein 2 Artist Bios Anne Clark Culbert 4 Bernarda Bryson Shahn 6 Alice Aycock 8 Jennifer Bartlett 10 Nancy Graves 12 Nancy Holt 14 Jenny Holzer 16 Sylvia Plimack Mangold 18 Elizabeth Murray 20 Louise Nevelson 22 Susan Rothenberg 24 Pat Steir 26 Jenny Holzer Table and Benches at Gordy Hall 1998 Photograph by Barbara Jewell Selected Bibliography 28 INTRODUCTION Dr. Jennie Klein omen Artists II is the second of a three-part exhibition inequities. This is not the case with the work included in this Greene, Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine de Kooning, and Joan Vermont. One of the founders of 17, Clark Culbert found herself in that examines the art of women artists in the collections of exhibition, which is composed primarily of prints and paintings, Mitchell. The work of Isabel M. Work and Katherine McQuaid- Athens after marrying Taylor Culbert, who taught English at Ohio WKennedy Museum of Art. This exhibition examines the work along with the whimsical clay sculptures of Anne Clark Culbert. Steiner, both of whom received their Master’s degrees from Ohio University. Shahn, wife of the well-known social realist painter of artists who began their careers in the late 60s and early 70s, at The difference between the first exhibition, which was comprised University, was exhibited alongside the work of their more famous Ben Shahn, was a native of Athens, Ohio. -

Download Issue (PDF)

wdmaqart WOMEN SHOOT WOMEN: Films About Women Artists The recent public television series "The Originals: Women in Art" has brought attention to this burgeoning film genre by Carrie Rickey pag e 4 NOTES FROM HOUSTON New York State's artist-delegate to the International Women's Year Convention in Houston, Texas in a personal report on her experiences in politics by Susan S ch w a lb pag e 9 SYLVIA SLEIGH: Portraits of Women in Art Sleigh's recent portrait series acknowledges historical roots as well as the contemporary activism of her subjects by Barbara Cavaliere ......................................................................pag e 12 TENTH STREET REVISITED: Another look at New York’s cooperative galleries of the 1950s WOMEN ARTISTS ON FILM Interviews with women artist/co-op members produce surprising answers to questions about that era by Nancy Ungar page 15 SPECIAL REPORT: W omen’s Caucus for Art/College Art Association 1978 Annual Meetings Com plete coverage of all WCA sessions and activities, plus an exclusive interview with Lee Anne Miller, new WCA president.................................................................................pag e 19 PRIMITIVISM AND WOMEN’S ART Are primitivism and mythology answers to the need for non-male definitions of the feminine? by Lawrence Alloway ......................................................................p a g e 31 SYLVIA SLEIGH GALLERY REVIEWS pa g e 34 REPORTS An Evening with Ten Connecticut Women Artists; WAIT Becomes WCA/Florida Chapter page 42 Cover: Alice Neel, subject of one of the new films about women artists, in her studio. Photo: Gyorgy Beke. WOMANART MAGAZINE Is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215, (212) 499-3357. -

Portraits” Proof

Vol. 2 No. 1 wdmaqartrrVlliftAIIUA l Fall 1977 OUT OF THE MAINSTREAM Two artists' attitudes about survival outside of New York City by Janet Heit page 4 19th CENTURY AMERICAN PRINTMAKERS A neglected group of women is revealed to have filled roles from colorist to Currier & Ives mainstay by Ann-Sargent Wooster page 6 INTERVIEW WITH BETTY PARSONS The septuagenarian artist and dealer speaks frankly about her relationship to the art world, its women, and the abstract expressionists by Helene Aylon .............................................................................. pag e 10 19th c. Printmakers MARIA VAN OOSTERWUCK This 17th century Dutch flower painter was commissioned and revered by the courts of Europe, but has since been forgotten by Rosa Lindenburg ........................................................................pag e ^ 6 STRANGERS WHEN WE MEET A 'how-to' portrait book reveals societal attitudes toward women by Lawrence A llo w a y ..................................................................... pag e 21 GALLERY REVIEWS ............................................................................page 22 EVA HESSE Combined review of Lucy Lippard's book and a recent retrospective exhibition by Jill Dunbar ...................................................................................p a g e 33 REPORTS Artists Support Women's Rights Day Activities, Bridgeport Artists' Studio—The Factory ........................................ p a g e 34 Betty Parsons W OMAN* ART*WORLD News items of interest page 35 Cover: Betty Parsons. Photo by Alexander Liberman. WOMANARTMAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises. 161 Prospect.Park West, Brooklyn. New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P.O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station. New York. N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 fo r one year. Application to mail at second class postage rates pending in Brooklyn. N. Y.