0 .TS2 C Ap'fc3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

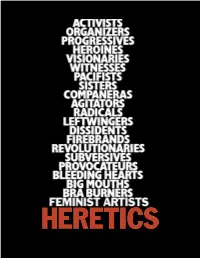

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

July 14–19, 2019 on the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University

July 14–19, 2019 On the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University OVER 30 years as Tennessee’s only Center of Excellence for the Creative Arts OVER 100 events per year OVER 85 acclaimed guest artists per year Masterclasses Publications Performances Exhibits Lectures Readings Community Classes Professional Learning for Educators School Field Trip Grants Student Scholarships Learn more about us at: Austin Peay State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, disability, age, status as a protected veteran, genetic information, or any other legally protected class with respect to all employment, programs and activities sponsored by APSU. The Premier Summer Teacher Training Institute for K–12 Arts Education The Tennessee Arts Academy is a project of the Tennessee Department of Education and is funded under a grant contract with the State of Tennessee. Major corporate, organizational, and individual funding support for the Tennessee Arts Academy is generously provided by: Significant sponsorship, scholarship, and event support is generously provided by the Belmont University Department of Art; Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee; Dorothy Gillespie Foundation; Solie Fott; Bobby Jean Frost; KHS America; Sara Savell; Lee Stites; Tennessee Book Company; The Big Payback; Theatrical Rights Worldwide; and Adolph Thornton Jr., aka Young Dolph. Welcome From the Governor of Tennessee Dear Educators, On behalf of the great State of Tennessee, it is my honor to welcome you to the 2019 Tennessee Arts Academy. We are so fortunate as a state to have a nationally recognized program for professional development in arts education. -

I OCT/NOV 1988 142 Ne W Zealan D Pos T Offic E Headquarters , Y MULMN T UAVI U / Ur\^W !\ E M.^L/!« L

,j , , M.^L/!«L ur\^W!\e / UAVIU MULMNt Y CSA Preview is registered at New Zealand Post Office Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine. PREVIE I OCT/NOV 1988 W 14 2 ~ The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Gallery Hours A 66 Gloucester Street Christchurch, Monday-Friday 10am-4.30pm • I New Zealand P.O. Box 772, Christchurch Saturday-Sunday 2pm-4.30pm | Phone 667-261,667-167. PREVIEW SOCIETY Dr G W Rice Roto Art Exhibition Andrew Anderson Centreplace, Hamilton, November 20-26 1988 OFFICERS Mrs Lyndel Diedrichs Entry forms by 14 October Mark Steyn Apply to: Patron J D and A C Allan Roto Art '88 Patricia Wood His Excellency The Governor General P O Box 5083 Juliet Nicholas The Most Reverend Paul Reeves GCMG, DCL Frankton, Hamilton (Oxon) Mr and Mrs Cooke Mr and Mrs P M M Bradshaw NZ Academy of Fine Arts President Sue Syme Abstractions David Sheppard. A.N.Z.I.A.. M.N.Z.P.I. Jo Sutherland National Bank Art Award 1988 Pamela Jamieson Vice-Presidents Receiving days 7-8 November N A Holland and J L Whyte Bill Cumming Season 27 November-11 December Mary Bulow Mrs Doris Holland Dorset House Innovation in Craft Jewel Oliver Timothy Baigent National Provident Fund Art Award 1988 Michael Eaton, Dip. F.A., Dip. Tchg.. F.R.S.A. Jenny Murray Receiving days 26 and 27 September Nola Barron Robyn Watson Season 23 October-6 November John Coley, Dip. F.A., Dip. Tchg. Ailsa Demsem Entry forms available from: Tiffany Thornley Council NZ Academy of Fine Arts Karen Purchas Alison Ryde, T.T.C. -

MAY STEVENS B. 1924 Boston, MA D. 2019 Santa Fe, NM

MAY STEVENS b. 1924 Boston, MA d. 2019 Santa Fe, NM Education 1988-89 Postdoctoral Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1960 MFA Equivalency, New York City Board of Education 1948 Art Students League, New York, NY 1948 Academie Julian, Paris, France 1946 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, MA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976-1981, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2017 Alice in the Garden, RYAN LEE, New York, NY Big Daddy Paper Doll, RLWindow, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2014 May Stevens: Fight the Power, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2013 May Stevens: Political Pop at ADAA, Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY 2012 May Stevens: The Big Daddy Series, National Academy of Design, New York, NY 2011 One Plus or Minus One, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2010 May Stevens: Crossing Time, I.D.E.A. Space at Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 2008 May Stevens: Paintings and Works on Paper, 1968-1975, Mary Ryan Gallery, NY 2007 ashes rock snow water: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Women, Words, and Water: Works on Paper by May Stevens, Rutgers University 2005 The Water Remembers: Paintings and Works on Paper from 1990- 2004, Springfield Museum of Art, Springfield, MO; traveled to the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, MN and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC 2005 New Works, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Deep River: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, CA 2000 -

A Finding Aid to the Elaine De Kooning Papers, Circa 1959-1989, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elaine de Kooning papers, circa 1959-1989, in the Archives of American Art Harriet E. Shapiro and Erin Kinhart 2015 October 21 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Personal Papers, circa 1960s-1989.......................................................... 4 Series 2: Interviews, Conversations, and Lectures, 1978-1988............................... 5 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1960s, 2013............................................................... 7 Series 4: Printed Material, 1961-1982.................................................................... -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

The Artpolitics of May Stevens' Work: Disrupting the Distribution of The

The Artpolitics of May Stevens’ work: disrupting the distribution of the sensible Abstract: In this paper I look into the life and art of May Stevens, an American working class woman, feminist and committed political activist. I am particularly interested in how Steven’s artwork is inextricably interwoven with her politics, constituting, as I will argue an assemblage of artpolitics. The discussion draws on Jacques Rancière’s analyses of the politics of aesthetics and particularly his notion of ‘the distribution of the sensible’. What I argue is that although Rancière’s approach to the politics of aesthetics illuminates an understanding and appreciation of Stevens’ art, his idea about the redistribution of the sensible is problematic. It is here that the notion of artpolitics as an assemblage opens up possibilities for a critical project that goes beyond the limitations of Rancière’s proposition. Key words: aesthetics, artpolitics, distribution of the sensible, narratives, women artists There’s an expression that I’ve used a lot, a quotation from Butler Yeats, who said that you have to choose between ‘perfection of the life, or of the work.’ I refuse to do that. I will not choose. (Hills, 2005: 11) In a series of in-depth conversations with Patricia Hill (2005), American artist May Stevens (1924-) rejects Yates’ suggestion above about the incompatibility of life and art and insists on keeping them together. It is this agonistic project of fusing life into art and art into life that I will discuss in this paper, focusing on a working class artist, feminist and politically committed activist, who erupted as an event in my overall project of writing a genealogy of the female self in art. -

Copyrighted Material

Contents Preface x Acknowledgements and Sources xii Introduction: Feminism–Art–Theory: Towards a (Political) Historiography 1 1 Overviews 8 Introduction 8 1.1 Gender in/of Culture 12 • Valerie Solanas, ‘Scum Manifesto’ (1968) 12 • Shulamith Firestone, ‘(Male) Culture’ (1970) 13 • Sherry B. Ortner, ‘Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?’ (1972) 17 • Carolee Schneemann, ‘From Tape no. 2 for Kitch’s Last Meal’ (1973) 26 1.2 Curating Feminisms 28 • Cornelia Butler, ‘Art and Feminism: An Ideology of Shifting Criteria’ (2007) 28 • Xabier Arakistain, ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: 86 Steps in 45 Years of Art and Feminism’ (2007) 33 • Mirjam Westen,COPYRIGHTED ‘rebelle: Introduction’ (2009) MATERIAL 35 2 Activism and Institutions 44 Introduction 44 2.1 Challenging Patriarchal Structures 51 • Women’s Ad Hoc Committee/Women Artists in Revolution/ WSABAL, ‘To the Viewing Public for the 1970 Whitney Annual Exhibition’ (1970) 51 • Monica Sjöö, ‘Art is a Revolutionary Act’ (1980) 52 • Guerrilla Girls, ‘The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist’ (1988) 54 0002230316.indd 5 12/22/2014 9:20:11 PM vi Contents • Mary Beth Edelson, ‘Male Grazing: An Open Letter to Thomas McEvilley’ (1989) 54 • Lubaina Himid, ‘In the Woodpile: Black Women Artists and the Modern Woman’ (1990) 60 • Jerry Saltz, ‘Where the Girls Aren’t’ (2006) 62 • East London Fawcett, ‘The Great East London Art Audit’ (2013) 64 2.2 Towards Feminist Structures 66 • WEB (West–East Coast Bag), ‘Consciousness‐Raising Rules’ (1972) 66 • Women’s Workshop, ‘A Brief History of the Women’s Workshop of the -

2006 Illustrated Parade Notes

© 2006, School of Design 1. Rex, King of Carnival, Monarch of Merr iment Rex’s float carries the King of Carnival and his pages through the streets of New Orleans on Mardi Gras day. 2. His Majesty’s Bandwagon A band rides on this permanent float to provide music for Rex and for those who greet him on the parade route. 3. The King’s Jesters Even the Monarch of Merriment needs jesters in his court. Rex’s jesters dress in Mardi Gras colors—purple, green, and gold. 4. The Boeuf Gras This is one of the oldest symbols of Mardi Gras, symbolizing the great feast on the day before Lent begins. 5. Title Float: “Beaux Arts and Letters” While Rex Processions of past years have presented the history and culture of far-flung civilizations, this year’s theme explores the joys and beauties of Rex’s own empire and domain. New Orleans has a long and rich artistic history and has produced a wealth of artists and writers of national and international renown. Sculptors and painters, writers and poets have called New Orleans home, and have found inspiration for their work in her history, culture, and landscapes. Mardi Gras, the celebration unique to this city, has influenced the work of many of our artists and writers. 6. John James Audubon (1785-1851) Audubon, the pre-eminent American painter of birds and wildlife, was born in Haiti and came to America at age eighteen, living in Pennsylvania and Kentucky before traveling south with little more than his gun and his painting equipment.