Oral History Interview with Harmony Hammond, 2008 September 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

Surface Work

Surface Work Private View 6 – 8pm, Wednesday 11 April 2018 11 April – 19 May 2018 Victoria Miro, Wharf Road, London N1 7RW 11 April – 16 June 2018 Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE Image: Adriana Varejão, Azulejão (Moon), 2018 Oil and plaster on canvas, 180 x 180cm. Photograph: Jaime Acioli © the artist, courtesy Victoria Miro, London / Venice Taking place across Victoria Miro’s London galleries, this international, cross-generational exhibition is a celebration of women artists who have shaped and transformed, and continue to influence and expand, the language and definition of abstract painting. More than 50 artists from North and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia are represented. The earliest work, an ink on paper work by the Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova, was completed in 1918. The most recent, by contemporary artists including Adriana Varejão, Svenja Deininger and Elizabeth Neel, have been made especially for the exhibition. A number of the artists in the exhibition were born in the final decades of the nineteenth century, while the youngest, Beirut-based Dala Nasser, was born in 1990. Work from every decade between 1918 and 2018 is featured. Surface Work takes its title from a quote by the Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell, who said: ‘Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work.’ The exhibition reflects the ways in which women have been at the heart of abstract art’s development over the past century, from those who propelled the language of abstraction forward, often with little recognition, to those who have built upon the legacy of earlier generations, using abstraction to open new paths to optical, emotional, cultural, and even political expression. -

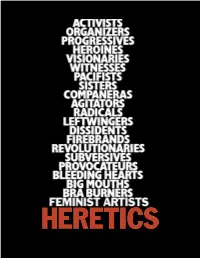

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Chryssa B. 1933, Athens D. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78

Chryssa b. 1933, Athens d. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78 Oil and graphite on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Michael Bennett 80.2717 Chryssa began making stamped paintings based on the New York Times in 1958 and continued to do so into the 1970s. To create these works, she had rubber stamps produced based on portions of the newspaper before, as she described it, covering “the entire area [of a canvas] with a fragment repeated precisely.” Over time Chryssa’s treatment of the motif became increasingly abstract, as she more strictly adhered to a gridded composition and selected sections of newsprint with type too small to be legibly rendered in rubber. By deemphasizing the content and format of the newspaper, she redirected focus to the tension between mechanized reproduction and her careful process of stamping by hand. Jacob El Hanani b. 1947, Casablanca Untitled #171 1976–77 Ink and acrylic on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Mr. and Mrs. George M. Jaffin 77.2291 With its dense profusion of finely drawn lines, Jacob El Hanani’s Untitled #171 is a feat of physical endurance, patience, and precision. As the artist said, “It is a personal challenge to bring drawing to the extreme and see how far my eyes and fingers can go.” Rather than approach this effort as an end unto itself, El Hanani has often related it to Jewish traditions of handwriting religious texts—a parallel suggesting a desire to transcend the self through a devotional level of discipline. This aspiration is given form in the way the short, variously weighted lines lose their discreteness from afar and blend into a vaporous whole. -

Moments in Time: Lithographs from the HWS Art Collection

IN TIME LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION PATRICIA MATHEWS KATHRYN VAUGHN ESSAYS BY: SARA GREENLEAF TIMOTHY STARR ‘08 DIANA HAYDOCK ‘09 ANNA WAGER ‘09 BARRY SAMAHA ‘10 EMILY SAROKIN ‘10 GRAPHIC DESIGN BY: ANNE WAKEMAN ‘09 PHOTOGRAPHY BY: LAUREN LONG HOBART & WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES 2009 MOMENTS IN TIME: LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION HIS EXHIBITION IS THE FIRST IN A SERIES INTENDED TO HIGHLIGHT THE HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES ART COLLECTION. THE ART COLLECTION OF HOBART TAND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES IS FOUNDED ON THE BELIEF THAT THE STUDY AND APPRECIATION OF ORIGINAL WORKS OF ART IS AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. IN LIGHT OF THIS EDUCATIONAL MISSION, WE OFFERED AN INTERNSHIP FOR ONE-HALF CREDIT TO STUDENTS OF HIGH STANDING TO RESEARCH AND WRITE THE CATALOGUE ENTRIES, UNDER OUR SUPERVISION, FOR EACH OBJECT IN THE EXHIBITION. THIS GAVE STUDENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN MUSEUM PRACTICE AS WELL AS TO ADD A PUBLICATION FOR THEIR RÉSUMÉ. FOR THIS FIRST EXHIBITION, WE HAVE CHOSEN TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE MORE IMPORTANT ARTISTS IN OUR LARGE COLLECTION OF LITHOGRAPHS AS WELL AS TO HIGHLIGHT A PRINT MEDIUM THAT PLAYED AN INFLUENTIAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF MODERN ART. OUR PRINT COLLECTION IS THE RICHEST AREA OF THE HWS COLLECTION, AND THIS EXHIBITION GIVES US THE OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF OUR MAJOR CONTRIBUTORS. ROBERT NORTH HAS BEEN ESPECIALLY GENER- OUS. IN THIS SMALL EXHIBITION ALONE, HE HAS DONATED, AMONG OTHERS, WORKS OF THE WELL-KNOWN ARTISTS ROMARE BEARDEN, GEORGE BELLOWS OF WHICH WE HAVE TWELVE, AND THOMAS HART BENTON – THE GREAT REGIONALIST ARTIST AND TEACHER OF JACKSON POLLOCK. -

Body As Matter and Process Press Release

Garth Greenan Gallery 529 West 20th Street 10th floor New York NY 10011 212 929 1351 www.garthgreenan.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Garth Greenan (212) 929-1351 [email protected] www.garthgreenan.com Skins: Body as Matter and Process Garth Greenan Gallery is pleased to announce Skins: Body as Matter and Process, a group exhibition curated by Alison Dillulio at 529 West 20th Street. Opening on Thursday, June 23, 2016, the exhibition features a selection of works, mostly from the 1970s, that evoke the human body–both literally and metaphorically. The artists included are: Lynda Benglis, Mary Beth Edelson, Harmony Hammond, Ralph Humphrey, Kiki Kogelnik, Howardena Pindell, Zilia Sánchez, Joan Semmel, Richard Van Buren, and Hannah Wilke. During the 1970s, second-wave feminism fostered a climate of unparalleled artistic innovation. As Lucy Lippard wrote, “the goal of feminism is to change the character of art.” The artists included in this exhibition furthered this mission by abandoning traditional art-making practices in favor of new modes of representation. They resisted preexisting patriarchal constructs by challenging the definition of painting and sculpture and reintegrating a palpable sense of self into their work. Howardena Pindell, Autobiography: Japan (Shisen-dö, Kyoto), 1982 (more) According to art historian Lynda Nead, art of this period “broke open the boundaries of representation….to reveal the body as matter and process, as opposed to form and stasis.” The featured artists cut, tear, stretch, throw, break apart, and reconstruct materials in their deeply personal and physically charged works. They reference the body in their exploration of processes, materials, and subject matter—an endeavor that offers viewers new perspectives on all forms, human and otherwise. -

MAY STEVENS B. 1924 Boston, MA D. 2019 Santa Fe, NM

MAY STEVENS b. 1924 Boston, MA d. 2019 Santa Fe, NM Education 1988-89 Postdoctoral Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1960 MFA Equivalency, New York City Board of Education 1948 Art Students League, New York, NY 1948 Academie Julian, Paris, France 1946 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, MA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Rosa Luxemburg, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1976-1981, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2017 Alice in the Garden, RYAN LEE, New York, NY Big Daddy Paper Doll, RLWindow, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2014 May Stevens: Fight the Power, RYAN LEE, New York, NY 2013 May Stevens: Political Pop at ADAA, Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY 2012 May Stevens: The Big Daddy Series, National Academy of Design, New York, NY 2011 One Plus or Minus One, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2010 May Stevens: Crossing Time, I.D.E.A. Space at Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 2008 May Stevens: Paintings and Works on Paper, 1968-1975, Mary Ryan Gallery, NY 2007 ashes rock snow water: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Women, Words, and Water: Works on Paper by May Stevens, Rutgers University 2005 The Water Remembers: Paintings and Works on Paper from 1990- 2004, Springfield Museum of Art, Springfield, MO; traveled to the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, MN and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC 2005 New Works, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Deep River: New Paintings and Works on Paper, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, CA 2000 -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4.