TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’S Collaborative Art + Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subrosa Tactical Biopolitics

14 Common Knowledge and Political Love subRosa . the body has been for women in capitalist society what the factory has been for male waged workers: the primary ground of their exploitation and resistance, as the female body has been appropriated by the state and men, and forced to function as a means for the reproduction and accumulation of labor. Thus the importance which the body in all its aspects—maternity, childbirth, sexuality—has acquired in feminist theory and women’s history has not been misplaced. silvia federici (2004, p. 16) Under capitalism, femininity and gender roles became a “labor” function, and women became a “labor class.”1 On one hand, women’s bodies and labor are revered and exploited as a “natural” resource, a biocommons or commonwealth that is fundamental to maintain- ing and continuing life: women are equated with “the lands,” “mother-earth,” or “the homelands.”2 On the other hand, women’s sexual and reproductive labor—motherhood, pregnancy, childbirth—is economically devalued and socially degraded. In the Biotech Century, women’s bodies have become fl esh labs and Pharma-commons: They are mined for eggs, embryonic tissues, and stem cells for use in medical, and therapeutic experiments, and are employed as gestational wombs in assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Under such conditions, resistant feminist discourses of the “body” emerge as an explicitly biopolitical practice.3 subRosa is a cyberfeminist collective of cultural producers whose practice creates dis- course and experiential knowledge about the intersections of information and biotechnolo- gies in women’s lives, work, and bodies. Since the year 2000, subRosa has produced a variety of performances, participatory events, installations, publications, and Web sites as (cyber)feminist responses to key issues in bio- and digital technologies. -

Oral History Interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7

Oral history interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview EW: EDITH WYLE SE: SHARON EMANUELLI SE: This is an interview for the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution. The interview is with Edith R. Wyle, on March 9th, Tuesday, 1993, at Mrs. Wyle's home in the Brentwood area of Los Angeles. The interviewer is Sharon K. Emanuelli. This is Tape 1, Side A. Okay, Edith, we're going to start talking about your early family background. EW: Okay. SE: What's your birth date and place of birth? EW: Place of birth, San Francisco. Birth date, are you ready for this? April 21st, 1918-though next to Beatrice [Wood-Ed.] that doesn't seem so old. SE: No, she's having her 100th birthday, isn't she? EW: Right. SE: Tell me about your grandparents. I guess it's your maternal grandparents that are especially interesting? EW: No, they all were. I mean, if you'd call that interesting. They were all anarchists. They came from Russia. SE: Together? All together? EW: No, but they knew each other. There was a group of Russians-Lithuanians and Russians-who were all revolutionaries that came over here from Russia, and they considered themselves intellectuals and they really were self-educated, but they were very learned. -

Faith Ringgold the Studiowith and Quilts That Tell Stories ART HIST RY KIDS

Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS THE GOLDEN AGE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE Art is connected to everything... music, history, science, math, literature, and more! Let’s explore how this month‘s art relates to some of these subjects. What is the Harlem Renaissance? From the 1910’s - the 1930’s the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem was booming with creativity. From fashion to food, music to dance, literature to art... amazing things were happening around every corner. This map illustrates the concentration of jazz clubs, restau- rants, and theaters in Harlem. As we spend this week connecting Faith Ringgold’s art to these other subjects, we’ll use her book, Harlem Renaissance Party, as our guide. Faith Ringgold’s book, Harlem Renaissance Party, takes us on a tour of the rich literary, culinary, musical, and theatrical scene in Harlem during the 1930’s. The following pages explore the Harlem Renaissance as Ringgold describes it in her book (and she should know, because she was actually there!) Click the image above to see a story time reading of the book! Illustration by Elmer Simms Campbell | Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library February 2019 | Week 3 1 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Geography The United States of America Here are maps of The United States of America, New York state, and Harlem – a neighborhood in the Manhattan borough of New New York State York City. February 2019 | Week 3 2 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Literature - Poetry + Folk Tales Langston Hughes Zora Neale Hurston 1936 photo by Carl Van Vechten Langston Hughes was one of the strongest Zora Neale Hurston wrote Mules and Men – literary voices during the Harlem Renaissance. -

Selected CV Joan Snyder

JOAN SNYDER Born April 16, 1940, in Highland Park, NJ. Received her A.B. from Douglass College, New Brunswick, NJ in 1962 and her M.F.A. from Rutgers, The State University, New Brunswick, NJ, in 1966. Currently lives and works in Brooklyn and Woodstock, NY. AWARDS 2016 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art 2007 The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship 1983 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship 1974 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship SELECTED SOLO & GROUP EXHIBITIONS SINCE 1972 2020 The Summer Becomes a Room, CANADA Gallery, New York, NY Friends and Family, curated by Keith Mayerson, Peter Mandenhall Gallery, Pasadena, CA Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY 2019-20 Art After Stonewall: 1969-1989, Leslie Lohman Museum of Art (NY), Columbus Museum of Art (OH), Patricia and Philip Frost Museum (FL). 2019 Rosebuds & Rivers, Blain|Southern, London, UK Painters Reply: Experimental Painting in the 1970s and now, curated by Alex Glauber & Alex Logsdail, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY Interwoven, curated by Janie M. Welker, The Art Museum at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY Contemporary American Works on Paper, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY Mulberry and Canal, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2018-20 Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY 2018-19 Six Chants and One Altar, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY 2018 Known: Unknown, NY Studio School, New York, NY Scenes From the Collection, The -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

Revisiting Cyberfeminism

AUTHOR’S COPY | AUTORENEXEMPLAR Revisiting cyberfeminism SUSANNA PAASONEN E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the early 1990s, cyberfeminism surfaced as an arena for critical analyses of the inter-connections of gender and new technology Ϫ especially so in the context of the internet, which was then emerging as something of a “mass-medium”. Scholars, activists and artists interested in media technol- ogy and its gendered underpinnings formed networks and groups. Conse- quently, they attached altering sets of meaning to the term cyberfeminism that ranged in their take on, and identifications with feminism. Cyberfemi- nist activities began to fade in the early 2000s and the term has since been used by some as synonymous with feminist studies of new media Ϫ yet much is also lost in such a conflation. This article investigates the histories of cyberfeminism from two interconnecting perspectives. First, it addresses the meanings of the prefix “cyber” in cyberfeminism. Second, it asks what kinds of critical and analytical positions cyberfeminist networks, events, projects and publications have entailed. Through these two perspectives, the article addresses the appeal and attraction of cyberfeminism and poses some tentative explanations for its appeal fading and for cyberfeminist activities being channelled into other networks and practiced under dif- ferent names. Keywords: cyberfeminism, gender, new technology, feminism, networks Introduction Generally speaking, cyberfeminism signifies feminist appropriation of information and computer technology (ICT) on a both practical and theoretical level. Critical analysis and rethinking of gendered power rela- tions related to digital technologies has been a mission of scholars but equally Ϫ and vocally Ϫ that of artists and activists, and those working in-between and across such categorizations. -

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

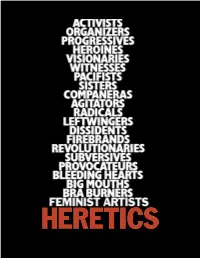

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

Aca Galleriesest. 1932

EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES Faith Ringgold Courtesy of ACA Galleries Faith Ringgold, American People Series #19: U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, 1967 th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES The Enduring Power of Faith Ringgold’s Art By Artsy Editors Aug 4, 2016 4:57 pm Portrait of Faith Ringgold. Photo by Grace Matthews. In 1967, a year of widespread race riots in America, Faith Ringgold painted a 12-foot-long canvas called American People Series #20: Die. The work shows a tumult of figures, both black and white, wielding weapons and spattered with blood. It was a watershed year for Ringgold, who, after struggling for a decade against the marginalization she faced as a black female artist, unveiled the monumental piece in her first solo exhibition at New York’s Spectrum Gallery. Earlier this year, several months after Ringgold turned 85, the painting was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, cementing her legacy as a pioneering artist and activist whose work remains searingly relevant. Where did she come from? Ringgold was born in Harlem in 1930. Her family included educators and creatives, and she grew up surrounded by the Harlem Renaissance. The street where she was raised was also home to influential activists, writers, and artists of the era—Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Dubois, and Aaron Douglas, to name a few. “It’s nice th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s...........................................................................