Jewish Museums - a Multi-Cultural Destination Sharing Jewish Art and Traditions with a Diverse Audience Jennifer B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected CV Joan Snyder

JOAN SNYDER Born April 16, 1940, in Highland Park, NJ. Received her A.B. from Douglass College, New Brunswick, NJ in 1962 and her M.F.A. from Rutgers, The State University, New Brunswick, NJ, in 1966. Currently lives and works in Brooklyn and Woodstock, NY. AWARDS 2016 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art 2007 The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship 1983 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship 1974 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship SELECTED SOLO & GROUP EXHIBITIONS SINCE 1972 2020 The Summer Becomes a Room, CANADA Gallery, New York, NY Friends and Family, curated by Keith Mayerson, Peter Mandenhall Gallery, Pasadena, CA Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY 2019-20 Art After Stonewall: 1969-1989, Leslie Lohman Museum of Art (NY), Columbus Museum of Art (OH), Patricia and Philip Frost Museum (FL). 2019 Rosebuds & Rivers, Blain|Southern, London, UK Painters Reply: Experimental Painting in the 1970s and now, curated by Alex Glauber & Alex Logsdail, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY Interwoven, curated by Janie M. Welker, The Art Museum at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY Contemporary American Works on Paper, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY Mulberry and Canal, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2018-20 Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY 2018-19 Six Chants and One Altar, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY 2018 Known: Unknown, NY Studio School, New York, NY Scenes From the Collection, The -

Museum Archivist

Newsletter of the Museum Archives Section Museum Archivist WINTER 2014 Volume 24 Issue 2 From the Co-Chairs Hello, and Happy New Year to everyone! more. In fact, we have adopted the follow- Although we may be in the frozen depths ing words by Benjamin Franklin that cap- of winter throughout much of the US, rest ture our inspiration and summarize our assured that your Museum Archives Sec- goals for the Museum Archives Section this tion (MAS) Co-Chairs, Jennie Thomas and year: “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I Heidi Abbey, have been busy not only remember. Involve me and I learn.” We reminiscing about the warm weather in are going to try to put these words into New Orleans during the 2013 annual practice. meeting, but also brainstorming ideas to facilitate participation from and communi- MAS Priorities for 2014 cation among our members. When we We will focus on three priorities for the began drafting our update for the newslet- rest of the year, and all of them will benefit ter, we were reminded of numerous con- from your involvement and feedback. We cerns raised by section members last Au- intend to: 1) improve communication tools gust. There was an overwhelming interest and information sharing, which will center in the value of talking to each other, collabo- around results from a spring 2014 survey rating more, and strengthening involvement of MAS members; 2) investigate the feasi- to make our section truly reflective of the bility and logistics of live streaming our diverse institutional and cultural heritage August 2014 annual meeting in Washing- Image by Lisa Longfellow. -

Your Family's Guide to Explore NYC for FREE with Your Cool Culture Pass

coolculture.org FAMILY2019-2020 GUIDE Your family’s guide to explore NYC for FREE with your Cool Culture Pass. Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org WELCOME TO COOL CULTURE! Whether you are a returning family or brand new to Cool Culture, we welcome you to a new year of family fun, cultural exploration and creativity. As the Executive Director of Cool Culture, I am excited to have your family become a part of ours. Founded in 1999, Cool Culture is a non-profit organization with a mission to amplify the voices of families and strengthen the power of historically marginalized communities through engagement with art and culture, both within cultural institutions and beyond. To that end, we have partnered with your child’s school to give your family FREE admission to almost 90 New York City museums, historic societies, gardens and zoos. As your child’s first teacher and advocate, we hope you find this guide useful in adding to the joy, community, and culture that are part of your family traditions! Candice Anderson Executive Director Cool Culture 2020 Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org HOW TO USE YOUR COOL CULTURE FAMILY PASS You + 4 = FREE Extras Are Extra Up to 5 people, including you, will be The Family Pass covers general admission. granted free admission with a Cool Culture You may need to pay extra fees for special Family Pass to approximately 90 museums, exhibits and activities. Please call the $ $ zoos and historic sites. museum if you’re unsure. $ More than 5 people total? Be prepared to It’s For Families pay additional admission fees. -

El Museo Del Barrio 50Th Anniversary Gala Honoring Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Raphael Montañez Ortíz, and Craig Robins

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EL MUSEO DEL BARRIO 50TH ANNIVERSARY GALA HONORING ELLA FONTANALS-CISNEROS, RAPHAEL MONTAÑEZ ORTÍZ, AND CRAIG ROBINS For images, click here and here New York, NY, May 5, 2019 - New York Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed from the stage of the Plaza Hotel 'Dia de El Museo del Barrio' at El Museo's 50th anniversary celebration, May 2, 2019. "The creation of El Museo is one of the moments where history started to change," said the Mayor as he presented an official proclamation from the City. This was only one of the surprises in a Gala evening that honored Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Craig Robins, and El Museo's founding director, artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz and raised in excess of $1.2 million. El Museo board chair Maria Eugenia Maury opened the evening with spirited remarks invoking Latina activist Dolores Huerta who said, "Walk the streets with us into history. Get off the sidewalk." The evening was MC'd by WNBC Correspondent Lynda Baquero with nearly 500 guests dancing in black tie. Executive director Patrick Charpenel expressed the feelings of many when he shared, "El Museo del Barrio is a museum created by and for the community in response to the cultural marginalization faced by Puerto Ricans in New York...Today, issues of representation and social justice remain central to Latinos in this country." 1230 Fifth Avenue 212.831.7272 New York, NY 10029 www.elmuseo.org Artist Rirkrit Travanija introduced longtime supporter Craig Robins who received the Outstanding Patron of Art and Design Award. Craig graciously shared, "The growth and impact of this museum is nothing short of extraordinary." El Museo chairman emeritus and artist, Tony Bechara, introduced Ella Fontanals-Cisneros who received the Outstanding Patron of the Arts award, noting her longtime support of Latin artists including early support Carmen Herrera, both thru acquiring her work and presenting it at her Miami institution, Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). -

Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 in & Around, NYC

2015 NEW YORK Association of Art Museum Curators 14th Annual Conference & Meeting May 9 – 12, 2015 Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 In & Around, NYC In addition to the more well known spots, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, , Smithsonian Design Museum, Hewitt, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Frick Collection, The Morgan Library and Museum, New-York Historical Society, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, here is a list of some other points of interest in the five boroughs and Newark, New Jersey area. Museums: Manhattan Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 (212) 288-6400 http://asiasociety.org/new-york Across the Fields of arts, business, culture, education, and policy, the Society provides insight and promotes mutual understanding among peoples, leaders and institutions oF Asia and United States in a global context. Bard Graduate Center Gallery 18 West 86th Street New York, NY 10024 (212) 501-3023 http://www.bgc.bard.edu/ Bard Graduate Center Gallery exhibitions explore new ways oF thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture. The Cloisters Museum and Garden 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tyron Park New York, NY 10040 (212) 923-3700 http://www.metmuseum.org/visit/visit-the-cloisters The Cloisters museum and gardens is a branch oF the Metropolitan Museum oF Art devoted to the art and architecture oF medieval Europe and was assembled From architectural elements, both domestic and religious, that largely date from the twelfth through fifteenth century. El Museo del Barrio 1230 FiFth Avenue New York, NY 10029 (212) 831-7272 http://www.elmuseo.org/ El Museo del Barrio is New York’s leading Latino cultural institution and welcomes visitors of all backgrounds to discover the artistic landscape of Puerto Rican, Caribbean, and Latin American cultures. -

WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT at SOUTH STREET SEAPORT: WHERE WATER and LAND, COLLABORATION and PLANNING CONVERGE Kathryn Anne Lorico Tipora Fordham University

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Urban Studies Masters Theses Urban Studies August 2012 WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT AT SOUTH STREET SEAPORT: WHERE WATER AND LAND, COLLABORATION AND PLANNING CONVERGE Kathryn Anne Lorico Tipora Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/urban_studies_masters Recommended Citation Tipora, Kathryn Anne Lorico, "WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT AT SOUTH STREET SEAPORT: WHERE WATER AND LAND, COLLABORATION AND PLANNING CONVERGE" (2012). Urban Studies Masters Theses. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/urban_studies_masters/2 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT AT SOUTH STREET SEAPORT: WHERE WATER AND LAND, COLLABORATION AND PLANNING CONVERGE BY Kathryn Anne Lorico Tipora BA, University of Richmond, 2007 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN STUDIES AT FORDHAM UNIVERSITY NEW YORK MAY 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND AND DEFINITIONS ................................................................... 6 LITERATURE REVIEW -

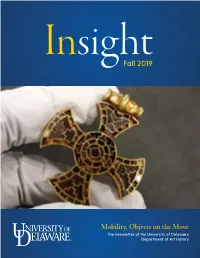

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

Eighteen Major New York Area Museums Participate in Instagram Swap

EIGHTEEN MAJOR NEW YORK AREA MUSEUMS PARTICIPATE IN INSTAGRAM SWAP THE FRICK COLLECTION PAIRS WITH NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY In a first-of-its-kind collaboration, eighteen major New York City area institutions have joined forces to celebrate their unique collections and spaces on Instagram. All day today, February 2, the museums will post photos from this exciting project. Each participating museum paired with a sister institution, then set out to take photographs at that institution, capturing objects and moments that resonated with their own collections, exhibitions, and themes. As anticipated, each organization’s unique focus offers a new perspective on their partner museum. Throughout the day, the Frick will showcase its recent visit to the New-York Historical Society on its Instagram feed using the hashtag #MuseumInstaSwap. Posts will emphasize the connections between the two museums and libraries, both cultural landmarks in New York and both beloved for highlighting the city’s rich history. The public is encouraged to follow and interact to discover what each museum’s Instagram staffer discovered in the other’s space. A complete list of participating museums follows: American Museum of Natural History @AMNH The Museum of Modern Art @themuseumofmodernart Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum @intrepidmuseum Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum @cooperhewitt Museum of the City of New York @MuseumofCityNY New Museum @newmuseum 1 The Museum of Arts and Design @madmuseum Whitney Museum of American Art @whitneymuseum The Frick Collection -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

New Museum Elects New Members to Its Board of Trustees, Joining Four Other Board Members Appointed Over the Past Year

PRESS CONTACTS Paul Jackson, Communications Director Nora Landes, Press Associate [email protected] 212.219.1222 x209 Andrea Schwan, Andrea Schwan Inc. 917.371.5023 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 10, 2020 NEW MUSEUM ELECTS NEW MEMBERS TO ITS BOARD OF TRUSTEES, JOINING FOUR OTHER BOARD MEMBERS APPOINTED OVER THE PAST YEAR New York, NY… Lisa Phillips, Toby Devan Lewis Director of the New Museum, and James Keith Brown, President, announced today the appointment of four new members elected to the New Museum’s Board of Trustees: Patricia Blanchet, Füsun EczacıbaŞı, Tommie Pegues, and Jamie Singer. They join four other new members who became trustees over the past year including Evan Chow, Randi Levine, Matt Mullenweg, and Marcus Weldon. “We are thrilled that these outstanding individuals committed to our mission are joining the New Museum Board,” said New Museum Board President, JK Brown. “Their diverse backgrounds across generations and geographies will bring new perspectives to the Museum for the future ahead at an important time of change,” said Lisa Phillips, Toby Devan Lewis Director. Patricia Blanchet has a long history of engagement with black arts and culture, as a maker, administrator, and patron, particularly of the visual arts, dance, theater, film, music, and photography. A longstanding collector of African American art, she currently serves on the Acquisition Committee of the Studio Museum in Harlem, and on the boards of the Newport Festivals Foundation and the NY African Film Festival. Previously she was the Program Director at NYU’s Institute of African American Affairs as well as the Director of Development at the Museum for African Art when it was the neighbor of the New Museum on Broadway. -

THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: from Idea to Institution

4 THE JOURNAL OF THE THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: From Idea to Institution BY BERYL K. SMITH Ms. Smith is Librarian at the Rutgers University Art Library During the 1960s, women began to identify and admit that social, political, and cultural inequities existed, and to seek redress. In 1966, a structural solidarity took shape with the founding of NOW (National Organization for Women). Women artists, sympathetic to the aims of this movement, recog- nized the need for a coalition with a more specific direction, and, at the height of the women's movement, several groups were formed that uniquely focused on issues of concern to women artists. In 1969 W.A.R. (Women Artists in Revolution) grew out of the Art Worker's Coalition, an anti- establishment group. In 1970 the Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee was formed, initially to increase the representation of women in the Whitney Museum annuals but later a more broad-based purpose of political and legal action and a program of regular discussions was adopted. Across the country, women artists were organizing in consciousness-raising sessions, joining hands in support groups, and picketing and protesting for the relief of injustices that they felt were rampant in the male-dominated art world. In January 1971, Linda Nochlin answered the question she posed in her now famous and widely cited article, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" Nochlin maintained that the exclusion of women from social and cultural institutions was the root cause that created a kind of cultural malnourishment of women.1 In June 1971, a new unity led the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists to threaten to sue the Los Angeles County Museum for discrimination.2 That same year, at Cal Arts (California In- stitute of the Arts) Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro developed the first women's art program in the nation.3 These bicoastal activities illustrate merely the high points of the women's art movement, forming an historical framework and providing the emotional climate for the beginning of the Women Artists Series at Douglass College. -

Jewish Sects - Spiritual World

ESTMINSTER Volume VIII No.4 October 2017 UARTERLY Cain slaying Abel by Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) From the Rabbi effect on the fate of the Jews of Europe. acceptance of converts for the purposes The whole of humanity and the political of the Law of Return whichever and social life were affected, stopping the movements or factions they come from. healthy evolution of the World. A further example is the inability to I am now reading another of Robert provide a place for all Jews without Harris’s books, Dictator, and my ‘must exception to worship at the Western read’ list includes Douglas Murray’s The Wall. It should not matter whether they Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, wish to have egalitarian services or if Identity, Islam. I am close to despair they firmly believe in, and practise, when I realise how little we have learnt equality between sexes. Surely both men from the wisdom of Ecclesiastes’s words, and women have a right not only to ‘That which hath been is that which shall worship together but also to enjoy the be, and that which hath been done is that beauty of holding and reading from the which shall be done; and there is nothing Torah Scroll. new under the sun’.(1:9) They are not As we look forward to Simchat Torah, as only painfully true but will remain so well as drawing wisdom from it – until we learn not to repeat the mistakes rejoicing and dancing - we should, in the Dear Friends of the past. Dictator impresses upon us New Year 5778, have a world with fewer that one day we can celebrate someone’s I very much hope that you have enjoyed a tears and more wisdom; a world without heroism and the next he can be lovely summer and have returned well extremism, giving us all a sense of having assassinated and that this really rested, refreshed, and ready to meet the learned from the past.