The 1977 Apple II Personal Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

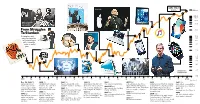

From Struggles to Stardom

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Steve Jobs – Who Blended Art with Technology

GENERAL ¨ ARTICLE Steve Jobs – Who Blended Art with Technology V Rajaraman Steve Jobs is well known as the creator of the famous Apple brand of computers and consumer products known for their user friendly interface and aesthetic design. In his short life he transformed a range of industries including personal comput- ing, publishing, animated movies, music distribution, mobile phones, and retailing. He was a charismatic inspirational leader of groups of engineers who designed the products he V Rajaraman is at the visualized. He was also a skilled negotiator and a genius in Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Several marketing. In this article, we present a brief overview of his generations of scientists life. and engineers in India have learnt computer 1. Introduction science using his lucidly written textbooks on Steve Jobs made several significant contributions which revolu- programming and tionized six industries, namely, personal computing, publishing, computer fundamentals. His current research animated movies, music distribution, mobile phones, and retail- interests are parallel ing digital products. In all these cases he was not the primary computing and history of inventor; rather he was a consummate entrepreneur and manager computing. who understood the potential of a technology, picked a team of talented engineers to create what he visualized, motivated them to perform well beyond what they thought they could do. He was an aesthete who instinctively blended art with technology. He hired the best industrial designers to design products which were not only easy to use but were also stunningly beautiful. He was a marketing genius who created demand for his products by leaking tit bits of information about their ‘revolutionary’ features, thereby building expectancy among prospective customers. -

Apple Products' Impact on Society

Apple Products’ Impact on Society Tasnim Eboo IT 103, Section 003 October 5, 2010 Honor Code: "By placing this statement on my webpage, I certify that I have read and understand the GMU Honor Code on http://academicintegrity.gmu.edu/honorcode/ . I am fully aware of the following sections of the Honor Code: Extent of the Honor Code, Responsibility of the Student and Penalty. In addition, I have received permission from the copyright holder for any copyrighted material that is displayed on my site. This includes quoting extensive amounts of text, any material copied directly from a web page and graphics/pictures that are copyrighted. This project or subject material has not been used in another class by me or any other student. Finally, I certify that this site is not for commercial purposes, which is a violation of the George Mason Responsible Use of Computing (RUC) Policy posted on http://universitypolicy.gmu.edu/1301gen.html web site." Introduction Apple was established in 1976 and has continuously since that date had an impact on our society today. Apple‟s products have grown year after year, with new inventions and additions to products coming out everyday. People have grown to not only recognize these advance items by their aesthetic appeal, but also by their easy to use methodology that has created a new phenomenon that almost everyone in the world knows about. With Apple‟s worldwide annual sales of $42.91 billion a year, one could say that they have most definitely succeeded at their task of selling these products to the majority of people. -

Quick Start for Apple Iigs

Quick Start for Apple IIGS Thank you for purchasing Uthernet II from A2RetroSystems, the best Ethernet card for the Apple II! Uthernet II is a 10/100 BaseTX network interface card that features an on- board TCP/IP stack. You will find that this card is compatible with most networking applications for the IIGS. Refer to the Uthernet II Manual for complete information. System Requirements Software • Apple IIGS ROM 01 or ROM 3 with one free slot Download the Marinetti TCP/IP 3.0b9 disk image at • System 6.0.1 or better http://a2retrosystems.com/Marinetti.htm • 2 MB of RAM or more 1. On the disk, launch Marinetti3.0B1 to install the first • Marinetti 3.0b9 or better part of Marinetti, then copy the TCPIP file from the • Hard drive and accelerator recommended disk into *:System:System.Setup, replacing the older TCPIP file. Finally, copy the UthernetII file into *:System:TCPIP 2. Restart your Apple IIGS, then choose Control Panels Installation Instructions from the Apple menu and open TCP/IP. Click Setup con- Uthernet II is typically installed in slot 3. nection... 3. From the Link layer popup menu, choose UthernetII. 1. Power off, and remove the cover of your Apple IIGS. 2. Touch the power supply to discharge any static elec- Click Configure..., then set your slot number in LAN Slot, and click the DHCP checkbox to automatically config- tricity. ure TCP/IP. Click Save, then OK, then Connect to network. 3. If necessary, remove one of the plastic covers from the back panel of the IIGS. -

Die Meilensteine Der Computer-, Elek

Das Poster der digitalen Evolution – Die Meilensteine der Computer-, Elektronik- und Telekommunikations-Geschichte bis 1977 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 und ... Von den Anfängen bis zu den Geburtswehen des PCs PC-Geburt Evolution einer neuen Industrie Business-Start PC-Etablierungsphase Benutzerfreundlichkeit wird gross geschrieben Durchbruch in der Geschäftswelt Das Zeitalter der Fensterdarstellung Online-Zeitalter Internet-Hype Wireless-Zeitalter Web 2.0/Start Cloud Computing Start des Tablet-Zeitalters AI (CC, Deep- und Machine-Learning), Internet der Dinge (IoT) und Augmented Reality (AR) Zukunftsvisionen Phasen aber A. Bowyer Cloud Wichtig Zählhilfsmittel der Frühzeit Logarithmische Rechenhilfsmittel Einzelanfertigungen von Rechenmaschinen Start der EDV Die 2. Computergeneration setzte ab 1955 auf die revolutionäre Transistor-Technik Der PC kommt Jobs mel- All-in-One- NAS-Konzept OLPC-Projekt: Dass Computer und Bausteine immer kleiner, det sich Konzepte Start der entwickelt Computing für die AI- schneller, billiger und energieoptimierter werden, Hardware Hände und Finger sind die ersten Wichtige "PC-Vorläufer" finden wir mit dem werden Massenpro- den ersten Akzeptanz: ist bekannt. Bei diesen Visionen geht es um die Symbole für die Mengendarstel- schon sehr früh bei Lernsystemen. iMac und inter- duktion des Open Source Unterstüt- möglichen zukünftigen Anwendungen, die mit 3D-Drucker zung und lung. Ägyptische Illustration des Beispiele sind: Berkley Enterprice mit neuem essant: XO-1-Laptops: neuen Technologien und Konzepte ermöglicht Veriton RepRap nicht Ersatz werden. -

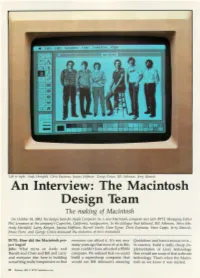

The Macintosh Design Team, February 1984, BYTE Magazine

Left to right: Andy Hertzfeld, Chris Espinosa, Joanna Hoffman , Geo rge Crowe, Bill Atkinson, Jern) Manock . An Interview: The Macintosh Design Team The making of Macintosh On October 14, 1983, the design team for Apple Computer Inc .'s new Macintosh computer met with BYTE Managing Editor Phil Lemmons at the company's Cupertino, California, headquarters. In the dialogue that followed , Bill Atkinson, Steve Jobs, Andy Hertzfeld, Larry Kenyon, Joanna Hoffman, Burrell Smith, Dave Egner, Chris Espinosa, Steve Capps, Jerry Manock, Bruce Horn , and George Crowe discussed the evolution of their brainchild. BYTE: How did the Macintosh pro everyone can afford it. It's not very Quickdraw and have a mouse on it ject begin? many years ago that most of us in this in essence, build a really cheap im Jobs: What turns on Andy and room couldn't have afforded a $5000 plementation of Lisa's technology Burrell and Chris and Bill and Larry computer. We realized that we could that would use some of that software and everyone else here is building build a supercheap computer that technology. That's when the Macin something really inexpensive so that would run Bill Atkinson's amazing tosh as we know it was started. 58 February 1984 © BYrE Publications Inc. Hertzfeld: That was around January of 1981. Smith: We fooled around with some other ideas for computer design, but we realized that the 68000 was a chip that had a future and had . .. Jobs: Some decent software! Smith: And had some horsepower and enough growth potential so we could build a machine that would live and that Apple could rally around for years to come. -

The History of the Ipad

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2015 Article 3 2016 The iH story of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Michael (2016) "The iH story of the iPad," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2015 , Article 3. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of the iPad Cover Page Footnote Thank you to Roger Williams University and Salve Regina University. This conference paper is available in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: http://docs.rwu.edu/ nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 Scully: iPad History The History of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this paper is to review the history of the iPad and its influence over contemporary computing. Although the iPad is relatively new, the tablet computer is having a long and lasting affect on how we communicate. With this essay, I attempt to review the technologies that emerged and converged to create the tablet computer. Of course, Apple and its iPad are at the center of this new computing movement. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

Allied Computer Store and the First Apple II Computer

Allied Computer Store and the first Apple II computer. By Michael Holley http://www.swtpc.com/mholley/Apple/allied_computer.htm Written Nov 2005, revised Feb 2016 When I was going to the College of San Mateo (1975-1977) I worked at a local computer store, Allied Computers. My job was to assemble computers kits. This included IMSAI, Processor Tech, SWTPC and any other kit that a customer wanted assembled. I would take my pay in computer parts. The first pay check was a SWTPC CT-1024 terminal followed by a SWTPC 6800 computer. By November of 1976 I had a complete system running BASIC. Chet Harris, the store owner, was trying to set up a chain like the Byte Shops and Computer Land. I got to meet some interesting people then, like a field trip to Bill Godbout's where we met Bill and George Morrow. Chet and I went to the Computer Shack store in San Leandro to talk with the management in early 1977. Radio Shack claimed trademark infringement on name Computer Shack so it was changed to Computer Land. One of our customers at Allied Computer was Bill Kelly. He was working for Regis McKenna Advertising on the Apple II introduction. He has a web page that talks about the early days at Apple Computer. (www.kelleyad.com/Histry.htm) He had worked on the Intel account and had an Intel SDK-80 evaluation board that he gave me in exchange for a power supply for his prototype Apple II board. (I still have that SDK-80 board with tiny BASIC.) We sold Apple II main boards before the plastic case was ready. -

Jerry Manock Collection of Apple History Ephemera M1880

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c82j6dzf No online items Guide to the Jerry Manock Collection of Apple History ephemera M1880 Finding aid prepared by Olin Laster Dept. of Special Collections & University Archives Stanford University Libraries. 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, California, 94305 Email: [email protected] 2012-4-16 Guide to the Jerry Manock M1880 1 Collection of Apple History ephemera M1880 Title: Jerry Manock Collection of Apple History ephemera Identifier/Call Number: M1880 Contributing Institution: Dept. of Special Collections & University Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 15.0 Linear feet(6 manuscript boxes, 5 record storage boxes, 3 flat boxes, 7 map folders; 1 optical disk and 4 cassettes.) Date (inclusive): 1966-2007 Physical Location: Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36-48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html. Abstract: This collection contains many blueprints, artifacts, and documentation of Manock's time both at Stanford University as an engineering student and at Apple as a product designer. Biography Jerrold Clifford Manock (born February 21, 1944) is an American industrial designer. He worked for Apple Computer from 1977 to 1984, contributing to housing designs for the Apple II, Apple III, and earlier compact Apple Macintosh computers. Manock is widely regarded as the "father" of the Apple Industrial Design Group. Since 1976 he is the president and principal designer of Manock Comprehensive Design, Inc., with offices in Palo Alto, California, and, after 1985, in Burlington, Vermont. -

Apple Ii Emulator Download

Apple ii emulator download click here to download Apple II emulator for Windows. Contribute to Find file. Clone or download . Download latest (stable) release: AppleWin v Release Notes: v Results 1 - 12 of 12 Sweet16 is the most capable Apple IIgs emulator for computers running Mac OS X. Based on the BeOS version of Sweet16, which was in turn. emutopia | emulation news and files. AppleWin runs Apple II programs from disk images, which are single files that contain the contents of an entire Apple. Sep 19, AppleWin is an Apple II emulator for Windows that is able to emulate an Apple II, II+ and IIe. It emulates the Extended Keyboard IIe (also known. microM8 is an enhanced Apple IIe emulator that allows you to "upcycle" classic games using 3D graphics Download microm8 for macOS, Windows or Linux. AppleWin is an open source software emulator for running Apple II programs in Download Applewin (K) Some emulators may require a system. Apple ][js and Apple //jse - An Apple ][ Emulator and them so no need to download & upload roms. Apple - II Series emulators on Windows and other platforms, free Apple - II Series emulator downloads, as well as savestates, hacks, cheats, utilities, and more. AppleWin is the best Apple IIe emulator we have encountered so far to play Apple II Search for and download an Apple IIe game file and copy it to the game. KEGS - Kent's Emulated GS. An Apple IIgs emulator for Mac OS X, Win32, Linux, and Unix/X Download version - Virtual Modem support. Download. apple ii emulator free download. -

Apple Imagewriter II Owners Manual 1985.Pdf

AfJp/£ II, II Plus, /le, /le, /11, Macintosh;' MadnfOSbXL/Lisa" 0 Copyright ©Copyright 1985, Apple Computer, Inc. for all Even though Apple has tested the software and reviewed nontextual material, graphics, figures, photographs, and the documentation, APPLE MAKES NO WARRANTY all computer program listings or code in any form, OR REPRESENTATION, EITHER EXPRESS OR including object and source code. All rights reserved. IMPLIED , WITH RESPECT TO SOFTWARE, ITS QUALITY, PERFORMANCE, MERCHANTABILITY, For some products, a multi-use license may be OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. AS purchased to allow the software to be used on more A RESULT, THIS SOFTWARE IS SOLD "AS IS," than one computer O\rnecl by the purchaser, including a AND YOU THE PURCHASER ARE ASSUMING THE shared-disk system. (Contact your authorized Apple ENTIRE RISK AS TO ITS QUALITY AND dealer for in formation on multi-use licenses.) PERFORMANCE. Apple, the Apple logo, AppleWorks, lmageWriter II , Lisa, IN NO EVENT WILL APPLE BE LIABLE FOR MacWorks, and Super Serial Carel are trademarks of DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR Apple Computer, Inc. CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES RESULTING FROM AppleCare is a registered service mark of Apple ANY DEFECT IN THE SOFTWARE OR ITS Computer, Inc. DOCUMENTATION, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. ln particular, Apple shall have no Macintosh is a trademark of Mcintosh Laboratory, Inc. liabili ty for any programs or data stored in or used with and is being used with express permission of its owner. Apple products, incl uding the costs of recovering such Printed in Japan. programs or data. THE WARRANTY AND REMEDIES SET FORTH Limited Warranty on Media and Replacement ABOVE ARE EXCLUSIVE AND IN LIEU OF ALL OTHERS, ORAL OR WRITTEN, EXPRESS OR If you discover physical defects in the manuals IMPLIED.