Orlandini's Antigona (Vendicata): Transformation of a Venetian Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, Concert Partner

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, concert partner The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Student Concerts are generously supported by Mrs. Gert Wharton and an anonymous donor. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges Sarah Greenfield for preparing the lesson plans for the Junior/Intermediate Student Concert Study Guide. Junior/Intermediate Level Student Concert Study Guide Study Concert Student Level Junior/Intermediate Table of Contents Table of Contents 1) Concert Overview & Repertoire Page 3 2) Composer Biographies and Programme Notes Page 4 - 11 3) Unit Overview & Lesson Plans Page 12 - 23 4) Lesson Plan Answer Key Page 24 - 30 5) Artist Biographies Page 32 - 34 6) Musical Terms Glossary Page 35 - 36 7) Instruments in the Orchestra Page 37 - 45 8) Orchestra Seating Chart Page 46 9) Musicians of the TSO Page 47 10) Concert Preparation Page 48 11) Evaluation Forms (teacher and student) Page 49 - 50 The TSO has created a free podcast to help you prepare your students for the Science @ the Symphony Student Concerts. This podcast includes excerpts from pieces featured on the programme, as well as information about the instruments featured in each selection. It is intended for use either in the classroom, or to be assigned as homework. To download the TSO Junior/Intermediate Student Concert podcast please visit www.tso.ca/studentconcerts, and follow the links on the top bar to Junior/Intermediate. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra wishes to thank its generous sponsors: SEASON PRESENTING SPONSOR OFFICIAL AIRLINE SEASON -

Two Operatic Seasons of Brothers Mingotti in Ljubljana

Prejeto / received: 30. 11. 2012. Odobreno / accepted: 19. 12. 2012. tWo OPERATIC SEASONS oF BROTHERS MINGOTTI IN LJUBLJANA METODA KOKOLE Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Ljubljana Izvleček: Brata Angelo in Pietro Mingotti, ki sta Abstract: The brothers Angelo and Pietro med 1736 in 1746 imela stalno gledališko posto- Mingotti between 1736 and 1746 based in Graz janko v Gradcu, sta v tem času priredila tudi dve organised during this period also two operatic operni sezoni v Ljubljani, in sicer v letih 1740 seasons in Ljubljana, one in 1740 and the other in 1742. Dve resni operi (Artaserse in Rosmira) in 1742. Two serious operas (Artaserse and s komičnimi intermezzi (Pimpinone e Vespetta) Rosmira) with comic intermezzi (Pimpinone e je leta 1740 pripravil Angelo Mingotti, dve leti Vespetta) were produced in 1740 by Angelo Min- zatem, tik pred svojim odhodom iz Gradca na gotti. Two years later, just before leaving Graz sever, pa je Pietro Mingotti priredil nadaljnji for the engagements in the North, Pietro Mingotti dve resni operi, in sicer Didone abbandonata in brought another two operas to Ljubljana, Didone Il Demetrio. Prvo je nato leta 1744 priredil tudi v abbandonata and Il Demetrio. The former was Hamburgu, kjer je pelo nekaj že znanih pevcev, ki performed also in 1744 in Hamburg with some so izvajali iz starejše partiture, morda tiste, ki jo of the same singers who apparently used mostly je impresarij preizkusil že v Gradcu in Ljubljani. an earlier score, possibly first checked out in Primerjalna analiza ljubljanskih predstav vseka- Graz and Ljubljana. The comparative analysis kor potrjuje dejstvo, da so bile te opera pretežno of productions in Ljubljana confirms that these lepljenke, čeprav Pietrova Didone abbandonata operas were mostly pasticcios. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde "Musikalisches Recycling - das ist doch noch gut?!" (1) Mit Nele Freudenberger Sendung: 22. Januar 2018 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde mit Nele Freudenberger 22. Januar – 26. Januar 2018 "Musikalisches Recycling - das ist doch noch gut?!" (1) Signet Mit Nele Freudenberger – guten Morgen! Heute starten wir mit unserer Wochenreihe zum Thema „musikalisches Recycling“. Das hat in der Musikgeschichte viel größere Spuren hinterlassen als man annehmen könnte. Fremde Themen werden ausgeliehen, bearbeitet, variiert, eigene Themen wieder verwendet. Sogar eine eigene Gattung ist aus dem musikalischen Recycling hervorgegangen: das Pasticcio – und mit dem werden wir uns heute eingehender beschäftigen (0:26) Titelmelodie Ein musikalisches Pasticcio wird in Deutschland auch „Flickenoper“ genannt. Dieser wenig schmeichelhafte Name sagt eigentlich schon alles. Zum einen bezeichnet er treffend das zugrunde liegende Kompositionsprinzip: handelt es sich doch um eine Art musikalisches Patchwork, das aus alten musikalischen Materialien besteht. Die können von einem oder mehreren Komponisten stammen. Zum anderen gibt es auch gleich eine ästhetische Einordnung, denn „Flickenoper“ klingt wenn nicht schon verächtlich, so doch wenigstens despektierlich. -

Un Felice Motezuma*

UN FELICE MOTEZUMA* MICHELE GIRARDI Quando l’amico carissimo Jürgen Maehder mi propose di curare l’edizione moderna del Motezuma di Paisiello all’interno di un progetto di ricerca da lui ideato e coordinato, le mie esperienze in ambito settecentesco erano assai limitate. Ora si sono allargate, ma la mia formazione e il mio gusto rimangono quelli di uno storico della musica moderna e contemporanea, e questo limite intendo denunciare apertis verbis prima di parlarvi del tema proposto. Confesso anche che nutrivo un forte pregiudizio nei confronti dell’opera seria settecentesca. Il contatto diretto con questa musica, nel corso dei mesi che ci sono voluti per trascrivere col computer il manoscritto autografo e approntarne una versione accettabile ma tuttora perfettibile, non ha migliorato i miei rapporti con quel genere, di cui il Motezuma è sotto ogni profilo un esempio tipico. Per le ragioni suesposte non aspettatevi che vi annoi con doviziose letture di cronache teatrali del tempo relative all’esito piú o meno felice del Motezuma di Paisiello, oppure con accurate biografie degli interpreti dell’opera. Anche perché non ho svolto ancora, colpevolmente, le necessarie ricerche negli archivi romani. Gli stretti limiti fissati per la consegna, avvenuta nel dicembre del 1991, mi hanno costretto a completare il lavoro basandomi unicamente sul microfilm dell’autografo, in vista di un’edizione provvisoria quanto urgente. Quando nominerò il luogo dove l’originale è conservato tutti capiranno perché mi sia stato impossibile verificare alcuni importanti dati. Si tratta della Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Napoli, ben cara al mio amico Michael Wittmann. Ora la conferma di Alberto Ronchey al Dicastero dei beni culturali, che auspico duratura nonostante le condizioni politiche attuali, dovrebbe consentirmi di portare a termine del tutto il mio impegno in vista della pubblicazione degli Atti di questo Convegno. -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

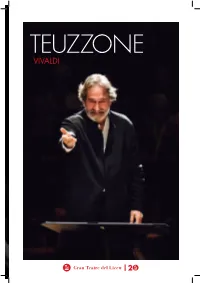

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Matthias Bernhard Braun auf seinem Weg nach Böhmen“ Verfasserin Anneliese Schallmeiner angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao Prof. Dr. Walter Krause Inhalt Seite I. Einleitung 4 II. Biographischer Abriss und Forschungslage 8 1. Biographischer Abriss zu Matthias Bernhard Braun 8 2. Forschungslage 13 III. Matthias Bernhard Braun auf seinem Weg nach Böhmen 22 1. Stilanalytische Überlegungen 22 2. Von Stams nach Plass/Plasy – Die Bedeutung des Zisterzienserordens – 27 Eine Hypothese 2.1. Brauns Arbeiten für das Zisterzienserkloster in Plass/Plasy 32 2.1.1. Die Kalvarienberggruppe 33 2.1.2. Die Verkündigungsgruppe 36 2.1.3. Der Bozzetto zur Statuengruppe der hl. Luitgard auf der Karlsbrücke 39 3. Die Statuengruppen auf der Karlsbrücke in Prag 41 3.1. Die Statuengruppe der hl. Luitgard 47 3.1.1. Kompositionelle und ikonographische Vorbilder 50 3.1.2. Visionäre und mysthische Vorbilder 52 3.2. Die Statuengruppe des hl. Ivo 54 3.2.1. Kompositionelle Vorbilder 54 3.2.2. Die Statue des hl. Franz Borgia von Ferdinand Maximilian Brokoff als 55 mögliches Vorbild für die Statue des hl. Ivo 4. Die Statue des hl. Judas Thaddäus 57 5. Brauns Beitrag zur Ausstattung der St. Klemenskirche in Prag 59 5.1. Evangelisten und Kirchenväter 60 5.2. Die Beichtstuhlaufsatzfiguren 63 6. Die Bedeutung des Grafen Franz Anton von Sporck für den Weg von 68 Matthias Bernhard Braun nach Böhmen 6.1. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

MUSIC in the EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY John Rice n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY NEW YORK ē LONDON W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program— trade books and college texts—were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: JoAnn Simony Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics—Fairfield, PA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rice, John A. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737).