KOINON the International Journal of Classical Numismatic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesop's Fables

aesop's fables ILLUSTRATED BY FKIT2^ KKEDEL ILLUSTr a TED JUNIo r LIBraru / aesop's fa b le s Illustrated Junior Library WITH DRAWINGS BY Fritz Kredel GROSSET Sc DUNLAP £•» Publishers The special contents of this edition are copyright © 1947 by Grosset & Dunlap, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published simultaneously in Canada. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 47-31077 ISBN: 0-448-11003-2 1987 P r in t in g THE DOC IN THE MANCER 1 THE WOLF IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING 2 MERCURY AND THE WOODMAN 3 THE FOX AND THE CROW 5 THE CARDENER AND HIS DOC 7 THE ANCLER AND THE LITTLE FISH 8 THE FAWN AND HER MOTHER 9 THE MILKMAID AND HER PAIL 10 THE ANT AND THE CRASSHOPPER 12 THE MICE IN COUNCIL 13 THE GNAT AND THE BULL 14 THE FOX AND THE GOAT 15 THE ASS CARRYING SALT 16 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 18 THE HARE WITH MANY FRIENDS 19 THE HARE AND THE HOUND 21 THE HOUSE DOC AND THE WOLF 22 THE GOOSE WITH THE GOLDEN ECCS 25 THE FOX AND THE HEDCEHOC 26 THE HORSE AND THE STAC 28 THE LION AND THE BULLS 30 THE GOATHERD AND THE GOATS 31 THE HARE AND THE TORTOISE 32 ANDROCLES AND THE LION 34 THE ANT AND THE DOVE 36 THE ONE-EYED DOE 37 THE ASS AND HIS MASTERS 38 THE LION AND THE DOLPHIN 39 THE ASSS SHADOW 41 THE ASS EATING THISTLES 42 THE HAWK AND THE PICEONS 44 THE BELLY AND THE OTHER MEMBERS 46 THE FROGS DESIRINC A KING 47 THE HEN AND THE FOX 49 THE CAT AND THE MICE 51 THE MILLER. -

The Tomb Architecture of Pisye–Pladasa Koinon

cedrus.akdeniz.edu.tr CEDRUS Cedrus VIII (2020) 351-381 The Journal of MCRI DOI: 10.13113/CEDRUS.202016 THE TOMB ARCHITECTURE OF PISYE – PLADASA KOINON PISYE – PLADASA KOINON’U MEZAR MİMARİSİ UFUK ÇÖRTÜK∗ Abstract: The survey area covers the Yeşilyurt (Pisye) plain Öz: Araştırma alanı, Muğla ili sınırları içinde, kuzeyde Ye- in the north, Sarnıçköy (Pladasa) and Akbük Bay in the şilyurt (Pisye) ovasından, güneyde Sarnıçköy (Pladasa) ve south, within the borders of Muğla. The epigraphic studies Akbük Koyu’nu da içine alan bölgeyi kapsamaktadır. Bu carried out in this area indicate the presence of a koinon alanda yapılan epigrafik araştırmalar bölgenin önemli iki between Pisye and Pladasa, the two significant cities in the kenti olan Pisye ve Pladasa arasında bir koinonun varlığını region. There are also settlements of Londeis (Çiftlikköy), işaret etmektedir. Koinonun territoriumu içinde Londeis Leukoideis (Çıpı), Koloneis (Yeniköy) in the territory of the (Çiftlikköy), Leukoideis (Çırpı), Koloneis (Yeniköy) yerle- koinon. During the surveys, many different types of burial şimleri de bulunmaktadır. Dağınık bir yerleşim modeli structures were encountered within the territory of the koi- sergileyen koinon territoriumunda gerçekleştirilen yüzey non, where a scattered settlement model is visible. This araştırmalarında farklı tiplerde birçok mezar yapıları ile de study particularly focuses on vaulted chamber tombs, karşılaşılmıştır. Bu çalışma ile özellikle territoriumdaki chamber tombs and rock-cut tombs in the territory. As a tonozlu oda mezarlar, oda mezarlar ve kaya oygu mezarlar result of the survey, 6 vaulted chamber tombs, 6 chamber üzerinde durulmuştur. Yapılan araştırmalar sonucunda 6 tombs and 16 rock-cut tombs were evaluated in this study. -

Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE Founder MRS. AUGUST BELMONT Honorary National Chairman ROBERT L. B. TOBIN National Chairman ELIHU M. HYNDMAN National Co-Chairmen MRS. NORRIS DARRELL GEORGE HOWERTON Profntional Committee KURT HERBERT ADLER BORIS GOLDOVSKY San Francisco Opera Goldovsky Opera Theatre WILFRED C. BAIN DAVID LLOYD Indiana University Lake George Opera Festival GRANT BEGLARIAN LOTFI MANSOURI University of So. California Canadian Opera Company MORITZ BOMHARD GLADYS MATHEW Kentucky Opera Association Community Opera SARAH CALDWELL RUSSELL D. PATTERSON Opera Company of Boston Lyric Opera of Kansas City TITO CAPOBIANCO MRS. JOHN DEWITT PELTZ San Diego Opera Metropolitan Opera KENNETH CASWELL EDWARD PURRINGTON Memphis Opera Theatre Tulsa Opera ROBERT J. COLLINGE GLYNN ROSS Baltimore Opera Company Seattle Opera Association JOHN CROSBY JULIUS RUDEL Santa Fe Opera New York City Opera WALTER DUCLOUX MARK SCHUBART University of Texas Lincoln Center ROBERT GAY ROGER L. STEVENS Northwestern University John F. Kennedy Center DAVID GOCKLEY GIDEON WALDROP Houston Grand Opera The Juilliard School Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol. 21, No. 4 • 1979/80 Editor, MARIA F. RICH Assistant Editor, JEANNE HANIFEE KEMP The COS Bulletin is published quarterly for its members by Central Opera Service. For membership information see back cover. Permission to quote is not necessary but kindly note source. Please send any news items suitable for mention in the COS Bulletin as well as performance information to The Editor, Central Opera Service Bulletin, Metropolitan Opera, Lincoln Center, New York, NY 10023. Copies this issue: $2.00 |$SN 0008-9508 NEW OPERAS AND PREMIERES Last season proved to be the most promising yet for new American NEW operas, their composers and librettists. -

Athenian 'Imperialism' in the Aegean Sea in the 4Th Century BCE: The

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 117–130 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.20.006.12796 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Athenian ‘Imperialism’ in the Aegean Sea in the 4th Century BCE: The Case of Keos* Wojciech Duszyński http:/orcid.org/0000-0002-9939-039X Jagiellonian University in Kraków Abstract: This article concerns the degree of direct involvement in the Athenian foreign policy in the 4th century BC. One of main questions debated by scholars is whether the Second Athe- nian Sea League was gradually evolving into an arche, to eventually resemble the league of the previous century. The following text contributes to the scholarly debate through a case study of relations between Athens and poleis on the island of Keos in 360s. Despite its small size, Keos included four settlements having the status of polis: Karthaia, Poiessa, Koresia and Ioulis, all members of the Second Athenian League. Around year 363/2 (according to the Attic calendar), anti-Athenian riots, usually described as revolts, erupted on Keos, to be quickly quelled by the strategos Chabrias. It is commonly assumed that the Athenians used the uprising to interfere di- rectly in internal affairs on the island, enforcing the dissolution of the local federation of poleis. However, my analysis of selected sources suggests that such an interpretation cannot be readily defended: in fact, the federation on Keos could have broken up earlier, possibly without any ex- ternal intervention. In result, it appears that the Athenians did not interfere in the local affairs to such a degree as it is often accepted. Keywords: Athens, Keos, Koresia, Karthaia, Poiessa, Ioulis, Aegean, 4th century BC, Second Athenian League, Imperialism. -

Aesop's Fables

451-CE2565 ☆ (CANADA $ 5.99) ☆ U.S. $4.95 AESOP’S FABLES Including: The Fox and the Grapes The Ants and the Grasshopper The Country Mouse and the City Mouse ...and 200 other famous fables SELECTED AND ADAPTED BY JACK ZIPES AESOP'S FABLES Selected and Adapted by Jack Zipes A SIGNET CLASSIC SIGNET CLASSIC Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York. New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd. Ringwood. Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd. 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd. Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex. England Published by Signet Classic, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. First Signet Classic Printing, October. 1992 10 987654321 Copyright © Jack Zipes. 1992 All rights reserved REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 92-60921 Printed in the United States of America BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MAR KETING DIVISION. PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC.. 375 HUDSON STREET. NEW YORK. NEW YORK 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Contents -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

The Antikythera Mechanism, Rhodes, and Epeiros

The Antikythera Mechanism, Rhodes, and Epeiros Paul Iversen Introduction I am particularly honored to be asked to contribute to this Festschrift in honor of James Evans. For the last nine years I have been engaged in studying the Games Dial and the calendar on the Metonic Spiral of the Antikythera Mechanism,1 and in that time I have come to admire James’s willingness to look at all sides of the evidence, and the way in which he conducts his research in an atmosphere of collaborative and curious inquiry combined with mutual respect. It has long been suggested that the Antikythera Mechanism may have been built on the is- land of Rhodes,2 one of the few locations attested in ancient literary sources associated with the production of such celestial devices. This paper will strengthen the thesis of a Rhodian origin for the Mechanism by demonstrating that the as-of-2008-undeciphered set of games in Year 4 on the Games Dial were the Halieia of Rhodes, a relatively minor set of games that were, appro- priately for the Mechanism, in honor of the sun-god, Helios (spelled Halios by the Doric Greeks). This paper will also summarize an argument that the calendar on the Metonic Spiral cannot be that of Syracuse, and that it is, contrary to the assertions of a prominent scholar in Epirote stud- ies, consistent with the Epirote calendar. This, coupled with the appearance of the extremely minor Naan games on the Games Dial, suggests that the Mechanism also had some connection with Epeiros. The Games Dial and the Halieia of Rhodes The application in the fall of 2005 of micro-focus X-ray computed tomography on the 82 surviv- ing fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism led to the exciting discovery and subsequent publi- cation in 2008 of a dial on the Antikythera Mechanism listing various athletic games now known as the Olympiad Dial (but which I will call the Games or Halieiad Dial—more on that below), as well as a hitherto unknown Greek civil calendar on what is now called the Metonic Spiral.3 I begin with my own composite drawing of the Games Dial (Fig. -

The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins

THE LEGEND OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT ON GREEK AND ROMAN COINS Karsten Dahmen collects, presents and examines, for the first time in one volume, the portraits and representations of Alexander the Great on ancient coins of the Greek and Roman periods (c. 320 bc to ad 400). Dahmen offers a firsthand insight into the posthumous appreciation of Alexander’s legend by Hellenistic kings, Greek cities, and Roman emperors combining an introduc- tion to the historical background and basic information on the coins with a comprehensive study of Alexander’s numismatic iconography. Dahmen also discusses in detail examples of coins with Alexander’s portrait, which are part of a selective presentation of representative coin-types. An image and discussion is combined with a characteristic quotation of a source from ancient historiography and a short bibliographical reference. The numismatic material presented, although being a representative selection, will exceed any previously published work on the subject. The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins will be useful for everyone in the Classics community including students and academics. It will also be accessible for general readers with an interest in ancient history, numismatics, or collecting. Karsten Dahmen is a Classical Archaeologist and Numismatist of the Berlin Coin Cabinet. http://avaxho.me/blogs/ChrisRedfield THE LEGEND OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT ON GREEK AND ROMAN COINS Karsten Dahmen First published 2007 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

Phillips / Seckinger Which of the Following Two Fables Has This Theme?

Determining Theme Phillips / Seckinger Which of the following two fables has this theme? Treat others as you would like to be treated The Tortoise and the Hare Once upon a time there was a hare who, boasting how he could run faster than anyone else, was forever teasing tortoise for its slowness. Then one day, the irate tortoise answered back: “Who do you think you are? There’s no denying you’re swift, but even you can be beaten!” The hare squealed with laughter. “Beaten in a race? By whom? Not you, surely! I bet there’s nobody in the world that can win against me, I’m so speedy. Now, why don’t you try?” Annoyed by such bragging, the tortoise accepted the challenge. A course was planned, and the next day at dawn they stood at the starting line. The hare yawned sleepily as the meek tortoise trudged slowly off. When the hare saw how painfully slow his rival was, he decided, half asleep on his feet, to have a quick nap. “Take your time!” he said. “I’ll have forty winks and catch up with you in a minute.” The hare woke with a start from a fitful sleep and gazed round, looking for the tortoise. But the creature was only a short distance away, having barely covered a third of the course. Breathing a sigh of relief, the hare decided he might as well have breakfast too, and off he went to munch some cabbages he had noticed in a nearby field. But the heavy meal and the hot sun made his eyelids droop. -

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE. NUMISMATIOUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE. PUBLU:.E. so~s LES A~SPICES nE LA snCIÉTÉ ROYALE nE NI,IM1SMAT lOUE AVEC LE CONCOURS DU GOUVERNEMENT DIRECTEURS: MM. MARCEL HOC, Dr JULES DESNEUX ET PAUL NASTER 1956 TOME CENT DEUXIÈME BRUXELLES 5, RUE DU MUSÉE 1956 KûINON Ir II()AEQN A Study of the Coinage of the ~ Ionian League)) (*) The coins which specifically refer to the thirteen cities of the Ionian Federation, KOINON 1r no/\ EON, bear the portraits of three emperors: Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelîus and Commodus, It is this series to which this article is devoted. There are two later issues of coins from the City of Colophon during the reigns ,ofTrebonianus Gallus and Valerian which have lîttle direct con- ....... ,,' :neèthm with the Ionian Federation as such. An example of the \\~.~~m.~p~~~:~;:d.P::~~;:~:~::~~i~eW;:~~ieD~ :>\Ve:are::d~ePiYlndebted: ACI{NOWLEDGEMENTS To the fpllowingfor valuable suggestions and assistance in ohtainlng material for thtsartfcle: Colin M~ Ki"aay, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Dr. T. O. Mahbott, Hunter College, New York. Sydney P. Noe, American Nunùsmatic Society, New York. Dr. David Magie) Princeton University. Edward Gans, Berkeley, California. H. Von Aulock, Istanbul. To the following for furnishing casts and photographs and assistance in procuring them: Dr. Karl Pink and Dr. Eduard Holzmair, National Collection, Vienna. Dr. W. Schneewind, Historlcal Museum, Basel. Miss Anne S. Robertson, Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow. M. Jean Babelon, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. P. K. .Ienkins, British Museum, London. Dr. G. Erxleben, National Museum, Berlin. Sr. Gian Guido Belloni, Sforza Museum, Milan. And to tlle following dealers for their generons cooperation: 32 .r. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 117 (1997) 129–132 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt Gmbh, Bonn

CARL A. ANDERSON – T. KEITH DIX POLITICS AND STATE RELIGION IN THE DELIAN LEAGUE: ATHENA AND APOLLO IN THE ETEOCARPATHIAN DECREE aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 117 (1997) 129–132 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 129 POLITICS AND STATE RELIGION IN THE DELIAN LEAGUE: ATHENA AND APOLLO IN THE ETEOCARPATHIAN DECREE The Eteocarpathian decree honors the koinon of the Eteocarpathians for sending a cypress beam from Apollo’s precinct on Carpathos to the temple of Athena ÉAyhn«n med°ou!a at Athens (IG i3 1454, Syll.3 1. 129). The title Athena ÉAyhn«n med°ou!a has been identified with Athena Polias of Athens, and its use here seemed to indicate that the decree was related to a group of inscriptions from Samos, Cos, and Colophon, which contain the same epithet of the goddess.1 The early fourth-century date once generally accepted for the decree, however, appeared to exclude it from this group of inscriptions, which were all dated to the mid-fifth century.2 Scholars have apparently resolved this problem by a redating of the decree, on the basis of letter-forms, to a period between 445-30 B.C.3 The purpose of this paper is to reconstruct the likely political and religious circumstances which underlie a fifth-century promulgation of the decree, while confirming identification of Athena ÉAyhn«n med°ou!a with Athena Polias at Athens, and to explore the implications of Apollo’s presence in the decree for Athenian religious propaganda on Carpathos.4 The provisions of the decree itself indicate that there were political difficulties on Carpathos. -

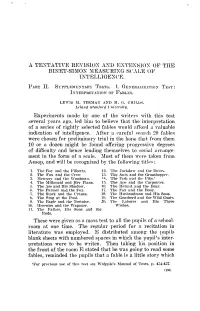

A Tentative Revision and Extension of the Binet-Simon Measuring Scale of Intelligence

A TENTATIVE REVISION AND EXTENSION OF THE BINET-SIMON MEASURING SCALE OF INTELLIGENCE. PART II. SUPPLEMENTARY TESTS. 1. GENERALIZATION TEST: INTERPRETATION OF FABLES. LEWIS M. TERMAX AND H. G. CHILDS. Lcland Stanford University. Experiments made by one of the writers with this test several years ago. led him to believe that the interpretation of a series of rightly selected fables would afford a valuable indication of intelligence. After a careful search 20 fables were chosen for preliminary trial in the hope that from them 10 or a dozen might be found offering progressive degrees of difficulty and hence lending themselves to serial arrange- ment in the form of a scale. Most of them were taken from Aesop, and will be recognized by the following title«; 1. The Boy and the Filberts. 12, The Jackdaw and the Doves. 2. The Fox and the Crow 13. The Ants and the Grasshopper. 3. Mercury and the Woodman. ">•*. The Fish and the Pike.1 4. The Milkmaid and Her Plans. 15. The Ape and the Carpeoter. 5. The Ass and His Shadow. 10, The Hermit and the Bear. C). The Fanner and the Fox. IT. The Fox and the Boar. T. The Stork and the Cr.iucs. 18. The Husbandman and His Sons. 8. The Stag at the Pool. J!>. The Goatherd and (lie Wild Goats. 0. The Eagle and the Tortoise. iO. The Laborer and Ills Three 10. Hercules and tiie AVagoner. Wishes. 11. The Father, His Sons and the Ttods. These were given as a mass test to all the pupils of a school- room at one time.