Chapter 3 Measuring Light Albert A. Michelson 1882 – 1889

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Henry

MEMOIR JOSEPH HENRY. SIMON NEWCOMB. BEAD BEFORE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OP SCIENCES, APRIL 21, 1880. (1) BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH HENRY. In presenting to the Academy the following notice of its late lamented President the writer feels that an apology is due for the imperfect manner in which he has been obliged to perform the duty assigned him. The very richness of the material has been a source of embarrassment. Few have any conception of the breadth of the field occupied by Professor Henry's researches, or of the number of scientific enterprises of which he was either the originator or the effective supporter. What, under the cir- cumstances, could be said within a brief space to show what the world owes to him has already been so well said by others that it would be impracticable to make a really new presentation without writing a volume. The Philosophical Society of this city has issued two notices which together cover almost the whole ground that the writer feels competent to occupy. The one is a personal biography—the affectionate and eloquent tribute of an old and attached friend; the other an exhaustive analysis of his scientific labors by an honored member of the society well known for his philosophic acumen.* The Regents of the Smithsonian Institution made known their indebtedness to his administration in the memorial services held in his honor in the Halls of Congress. Under these circumstances the onl}*- practicable course has seemed to be to give a condensed resume of Professor Henry's life and works, by which any small occasional gaps in previous notices might be filled. -

Physics and Astronomy (Classes QB, QC, and Selected Portions of Z)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTIONS POLICY STATEMENTS Physics and Astronomy (Classes QB, QC, and selected portions of Z) Contents I. Scope II. Research strengths III. Collecting policy IV. Acquisition sources V. Best editions and preferred formats VI. Collecting levels I. Scope The Collections Policy Statement on Physics and Astronomy covers the subclasses of QB (Astronomy) and QC (Physics), as well as the corresponding subclasses of Class Z. In addition, some of the numerous abstracting and indexing services, catalogs of other scientific libraries, and specialized bibliographic finding aids for these fields are classed in Z. See also the related Collections Policy Statements for Chemical Sciences and Technology. II. Research strengths A. General The Library’s collecting strength in subclasses QB and QC is generally at the research level. The Library has long runs of many important serials such as American Journal of Physics, Journal of Applied Physics, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, and other publications of notable societies and associations, as well as the major abstracting and indexing services in physics and astronomy including Science Abstracts. Series A, Physics Abstracts, and its predecessors, and Astronomischer Jahresbericht and its successor, Astronomy and Astrophysics Abstracts. The Library’s extensive general collections in physics and astronomy are further enhanced by the numerous technical reports held in the Automation, Collections Support & Technical Reports Section, and by specialized materials held by the Manuscript, Rare Book and Special Collections, Geography and Map, and Prints and Photographs Divisions. In addition, the Library’s already extensive collection of U.S. astronomy and physics dissertations in microform is now supplemented by the digital dissertations archive from the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global database. -

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix As Projections of Higher-Dimensional La�Ices in Sco� Joplin’S Music *

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix as Projections of Higher-Dimensional Laices in Sco Joplin’s Music * Joshua W. Hahn NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.2/mto.21.27.2.hahn.php KEYWORDS: meter, rhythm, beat class theory, syncopation, ragtime, poetry, hyperspace, Joplin, Du Bois ABSTRACT: Generated rhythms and the metric matrix can both be modelled by time-domain equivalents to projections of higher-dimensional laices. Sco Joplin’s music is a case study for how these structures can illuminate both musical and philosophical aims. Musically, laice projections show how Joplin creates a sense of multiple beat streams unfolding at once. Philosophically, these structures sonically reinforce a Du Boisian approach to understanding Joplin’s work. Received August 2019 Volume 27, Number 2, June 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory Introduction [1] “Dr. Du Bois, I’ve read and reread your Souls of Black Folk,” writes Julius Monroe Troer, the protagonist of Tyehimba Jess’s 2017 Pulier Prize-winning work of poetry, Olio. “And with this small bundle of voices I hope to repay the debt and become, in some small sense, a fellow traveler along your course” (Jess 2016, 11). Jess’s Julius Monroe Troer is a fictional character inspired by James Monroe Troer (1842–1892), a Black historian who catalogued Black musical accomplishments.(1) In Jess’s narrative, Troer writes to W. E. B. Du Bois to persuade him to help publish composer Sco Joplin’s life story. -

Life Sciences, Physical Sciences, Earth and Environmental Sciences

COLLECTION OVERVIEW LIFE SCIENCES, PHYSICAL SCIENCES, EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES I. SCOPE The life, physical, earth and environmental sciences collections include botany (LC Class QK), biology, natural history, ecology, genetics (LC Class QH), zoology (LC Class QL), human anatomy (LC Class QM), physiology (LC Class QP), microbiology (LC Class QR) astronomy (LC Class QB), physics (LC Class QC), paleontology (LC Class QE), geology (LC Class QE), oceanography (LC Class GC), environmental sciences (LC Class GE), agriculture (LC Class S), medicine (LC Class R), and associated materials classed in bibliography, indexes, and abstracting services (LC Class Z). II. SIZE The Library's collections in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences number 2,145,294 titles. While the Library of Congress has deferred to the National Library of Medicine for the acquisition of clinical medicine since the early 1950s, its collection of medical journals, texts, and monographs exceeds 320,000 titles. For the same period of time, the Library has also deferred acquisition of technical agriculture and the veterinary sciences to the National Agricultural Library, yet the Library holds over 222,294 titles of importance to the Congress and its many constituencies in this subject area. III. GENERAL RESEARCH STRENGTHS The Library's collections in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences are exceptional and, as in the case of the Library's general science and technology collections, have profited greatly from the materials generated by the Smithsonian and copyright deposits. These programs provided and still provide the Library with long, unbroken runs of proceedings, memoirs, monographic series, and journals in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences. -

Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Wible, James R.; Hoover, Kevin D. Working Paper Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S. Peirce's Engagement with Cournot's Recherches sur les Principes Mathematiques de la Theorie des Richesses CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2013-12 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Wible, James R.; Hoover, Kevin D. (2013) : Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S. Peirce's Engagement with Cournot's Recherches sur les Principes Mathematiques de la Theorie des Richesses, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2013-12, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/149703 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

![Environmental History] Orosz, Joel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6654/environmental-history-orosz-joel-2026654.webp)

Environmental History] Orosz, Joel

Amrys O. Williams Science in America Preliminary Exam Reading List, 2008 Supervised by Gregg Mitman Classics, Overviews, and Syntheses Robert Bruce, The Launching of Modern American Science, 1846-1876 (New York: Knopf, 1987). George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968). ————, Science in American Society (New York: Knopf, 1971). Sally Gregory Kohlstedt and Margaret Rossiter (eds.), Historical Writing on American Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). Ronald L. Numbers and Charles Rosenberg (eds.), The Scientific Enterprise in America: Readings from Isis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). Nathan Reingold, Science, American Style. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991). Charles Rosenberg, No Other Gods: On Science and American Social Thought (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976). Science in the Colonies Joyce Chaplin, Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo- American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). [crosslisted with History of Technology] John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984). Katalin Harkányi, The Natural Sciences and American Scientists in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990). Brooke Hindle, The Pursuit of Science in Revolutionary America, 1735-1789. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956). Judith A. McGaw, Early American Technology: Making and Doing Things from the Colonial Era to 1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1994). [crosslisted with History of Technology] Elizabeth Wagner Reed, American Women in Science Before the Civil War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992). -

Biographical File, 1862-1927 and Undated

Biographical File, 1862-1927 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Biographical File https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217387 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Biographical File Identifier: Record Unit 7230 Date: 1862-1927 and undated Extent: 9.5 cu. ft. (19 document boxes) Creator:: United States National Museum. Department of Geology Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7230, United States National Museum. Department of Geology, Biographical File Descriptive Entry This biographical file was maintained by the United States National Museum's Department of Geology and several of its curators. Included in the file are biographies, obituaries, -

Letter from Simon Newcomb to Alexander Graham Bell, August 12, 1904

Library of Congress Letter from Simon Newcomb to Alexander Graham Bell, August 12, 1904 DAVID R. FRANCIS FREDERICK W. LEHMANN President Universal Exposition Chairman Committee Board of Directors UNIVERSAL EXPOSITION, ST. LOUIS ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD: 1904 Congress of Arts and Science ; NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER, LL. D. President Columbia University, New York WILLIAM R. HARPER, LL. D. INTERNATIONAL CONGRESSES PRESIDENT: President University of Chicago. SIMON NEWCOMB, LL. D. R. H. JESSE, LL. D. Washington D. C. President University of Missouri HOWARD J. ROGERS, Director Of Congresses HENRY R. PRITCHETT, LL. D. VICE-PRESIDENTS: President Massachusetts Inst. Technology. HUGO MUENSTERBERG, LL. D. HERBERT PUTNAM, LITT. D. Librarian of Congress. Harvard University. FREDERICK J. V. SKIEF, ALBION W. SMALL, LL. D. Director Field Columbia Museum. University of Chicago. Scientific duties Invitation & Gift-100 St. Louis , U. S. A. 530 Bond Building, Washington, D. C. August 12, 1904. Dear Dr. Bell: Most of the European delegates to the International Congress of Arts and Science, to the number of probably between fifty and eighty, will come to Washington immediately after the Congress, in order to pay their respects to the President, and see our city and its institutions. This occasion would offer such a rare opportunity of enabling a few of our scientific men and other citizens to meet a large body of eminent men from various countries, that I have for some time had it in view to arrange a reception. The date would probably be Wednesday, September 28. I have, until recently, supposed that so few people would then be at home that only a small number of invitations would be accepted, and I would be able to handle the whole matter myself. -

Telescopes and the Popularization of Astronomy in the Twentieth Century Gary Leonard Cameron Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century Gary Leonard Cameron Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Cameron, Gary Leonard, "Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11795. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11795 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century by Gary Leonard Cameron A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Science and Technology Program of study committee: Amy S. Bix, Major Professor James T. Andrews David B. Wilson John Monroe Steven Kawaler Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright © Gary Leonard Cameron, 2010. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Forward and Acknowledgements iv Dissertation Abstract v Chapter I: Introduction 1 1. General introduction 1 2. Research methodology 8 3. Historiography 9 4. Popularization – definitions 16 5. What is an amateur astronomer? 19 6. Technical definitions – telescope types 26 7. Comparison with other science & technology related hobbies 33 Chapter II: Perfecting ‘A Sharper Image’: the Manufacture and Marketing of Telescopes to the Early 20th Century 39 1. -

The Charles S. Peirce-Simon Newcomb Correspondence

The Charles S. Peirce-Simon Newcomb Correspondence Carolyn Eisele Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 101, No. 5. (Oct. 31, 1957), pp. 409-433. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-049X%2819571031%29101%3A5%3C409%3ATCSPNC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society is currently published by American Philosophical Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/amps.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 11 07:51:41 2008 THE CHARLES S. -

Simon Newcomb

SIMON NEWCOMB G. H. HENDERSON HEN Simon Newcomb died in 1909, he was universally W mourned as America's most eminent scientist. The Royal Society of London had given him its highest honour, the Copley Medal, and the French Academy of Sciences had elected him Foreign Associate in succession to Helmholtz. The United States, the land of his adoption, had granted him every honour it had to bestow. In view of all this, it is strange that few in this province know that Newcomb was born in Nova Scotia and spent the first eighteen years of his life in the Maritime Provinces. Such lack of honour in his own country is the more surprising since it is of intellectual achievement that a Nova Scotian is most prone to boast. He may be able to restrain himself modestly when speaking of a fellow countryman's success in business or in statesmanship; but when it comes to scholarship, his reticence is sorely tried. Perhaps one reason for this neglect of Newcomb is that his . work was in the abstruse subject of mathematical astronomy. , Only the specialist would be interested in the majority of his writings, . a partial list of which covers twenty-two closely printed pages. A wide appeal, however, is made by his Reminiscences of an Astronomer, written in the closing years of an eventful life. The .layman might be tempted to open its pages to learn something of that curious human variety, the great mathematician. He would find a very entertaining book, written by a practised hand·in a pleasing style. -

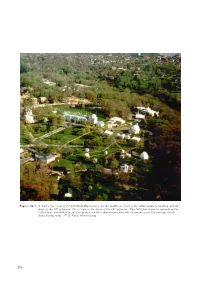

Figure 23.1: a “Bird's Eye” View of the US Naval Observatory. in the Middle at Center Is the Administration Building

Figure 23.1: A “bird’s eye” view of the US Naval Observatory. In the middle at center is the administration building and the dome of the 1200 refractor. To its right is the dome of the 2600 refractor. The 1000 foot diameter grounds of the USNO were established in 1890 to protect sensitive instruments from the vibrations caused by carriage wheels along nearby roads. (U. S. Naval Observatory) 216 23. U. S. Naval Observatory: The Move to Georgetown Heights and Double Star Work (1850–1950) Brian Mason (Washington, D.C., USA) Abstract with the dropping at noon of the time ball from the mast above the dome at the top of the Observatory. Despite Founded in 1830 as the Depot of Charts and Instruments, the purchasing much of the equipment of the observatory, U. S. Naval Observatory (USNO) is one of the oldest continu- being the last officer in charge of the Depot, and de- ously operational scientific institutions in the United States. signing the observatory, James Gilliss was not selected Among its first tasks were testing, rating and evaluation of as the first superintendent of the USNO. Instead, that various US Navy equipment (such as ships’ chronometers) as distinction went to Matthew Fontaine Maury. While well as the dissemination of time, first through its historic Maury learned the observational work of the USNO, he time ball and later through direct input via the Western is most well known as the father of the new science of Union telegraph. Fundamental Astrometry and maintenance Oceanography. of the Fundamental Reference Frame were among its ear- In 1861, when Maury resigned his Navy Commission liest charters.