Figure 23.1: a “Bird's Eye” View of the US Naval Observatory. in the Middle at Center Is the Administration Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Henry

MEMOIR JOSEPH HENRY. SIMON NEWCOMB. BEAD BEFORE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OP SCIENCES, APRIL 21, 1880. (1) BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH HENRY. In presenting to the Academy the following notice of its late lamented President the writer feels that an apology is due for the imperfect manner in which he has been obliged to perform the duty assigned him. The very richness of the material has been a source of embarrassment. Few have any conception of the breadth of the field occupied by Professor Henry's researches, or of the number of scientific enterprises of which he was either the originator or the effective supporter. What, under the cir- cumstances, could be said within a brief space to show what the world owes to him has already been so well said by others that it would be impracticable to make a really new presentation without writing a volume. The Philosophical Society of this city has issued two notices which together cover almost the whole ground that the writer feels competent to occupy. The one is a personal biography—the affectionate and eloquent tribute of an old and attached friend; the other an exhaustive analysis of his scientific labors by an honored member of the society well known for his philosophic acumen.* The Regents of the Smithsonian Institution made known their indebtedness to his administration in the memorial services held in his honor in the Halls of Congress. Under these circumstances the onl}*- practicable course has seemed to be to give a condensed resume of Professor Henry's life and works, by which any small occasional gaps in previous notices might be filled. -

Physics and Astronomy (Classes QB, QC, and Selected Portions of Z)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTIONS POLICY STATEMENTS Physics and Astronomy (Classes QB, QC, and selected portions of Z) Contents I. Scope II. Research strengths III. Collecting policy IV. Acquisition sources V. Best editions and preferred formats VI. Collecting levels I. Scope The Collections Policy Statement on Physics and Astronomy covers the subclasses of QB (Astronomy) and QC (Physics), as well as the corresponding subclasses of Class Z. In addition, some of the numerous abstracting and indexing services, catalogs of other scientific libraries, and specialized bibliographic finding aids for these fields are classed in Z. See also the related Collections Policy Statements for Chemical Sciences and Technology. II. Research strengths A. General The Library’s collecting strength in subclasses QB and QC is generally at the research level. The Library has long runs of many important serials such as American Journal of Physics, Journal of Applied Physics, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, and other publications of notable societies and associations, as well as the major abstracting and indexing services in physics and astronomy including Science Abstracts. Series A, Physics Abstracts, and its predecessors, and Astronomischer Jahresbericht and its successor, Astronomy and Astrophysics Abstracts. The Library’s extensive general collections in physics and astronomy are further enhanced by the numerous technical reports held in the Automation, Collections Support & Technical Reports Section, and by specialized materials held by the Manuscript, Rare Book and Special Collections, Geography and Map, and Prints and Photographs Divisions. In addition, the Library’s already extensive collection of U.S. astronomy and physics dissertations in microform is now supplemented by the digital dissertations archive from the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global database. -

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

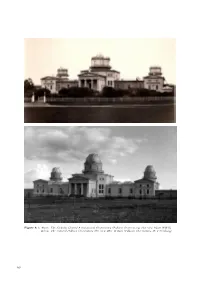

(Pulkovo Observatory) (The View Before WWII) Below: the Restored Pulkovo Observatory (The View After WWII) (Pulkovo Observatory, St

Figure 6.1: Above: The Nicholas Central Astronomical Observatory (Pulkovo Observatory) (the view before WWII) Below: The restored Pulkovo Observatory (the view after WWII) (Pulkovo Observatory, St. Petersburg) 60 6. The Pulkovo Observatory on the Centuries’ Borderline Viktor K. Abalakin (St. Petersburg, Russia) in Astronomy” presented in 1866 to the Saint-Petersburg Academy of Sciences. The wide-scale astrophysical studies were performed at Pulkovo Observatory around 1900 during the directorship of Theodore Bredikhin, Oscar Backlund and Aristarchos Be- lopolsky. The Nicholas Central Astronomical Observatory at Pulkovo, now the Central (Pulkovo) Astronomical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences, had been co-founded by Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve (1793–1864) [Fig. 6.2] together with the All-Russian Emperor Nicholas the First [Fig. 6.3] and inaugurated in 1839. The Observatory had been erected on the Pulkovo Heights (the Pulkovo Hill) near Saint-Petersburg in ac- cordance with the design of Alexander Pavlovich Brül- low, [Fig. 6.3] the well-known architect of the Russian Empire. [Fig. 6.4: Plan of the Observatory] From the very beginning, the traditional field of re- search work of the Observatory was Astrometry – i. e. determination of precise coordinates of stars from the observations and derivation of absolute star catalogues for the epochs of 1845.0, 1865.0 and 1885.0 (the later catalogues were derived for epochs of 1905.0 and 1930.0); they contained positions of 374 through 558 bright, so- called fundamental, stars. It is due to these extraordi- Figure 6.2: Friedrich Georg Wilhelm (Vasily Yakovlevich) narily precise Pulkovo catalogues that Benjamin Gould Struve (1793–1864), director 1834 to 1862 had called the Pulkovo Observatory the “astronomical (Courtesy of Pulkovo Observatory, St. -

Observations of the Satellites of the Major Planets at Pulkovo Observatory: History and Present N

Astronomy and Astrophysics in the Gaia sky Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 330, 2017 A. Recio-Blanco, P. de Laverny, A.G.A. Brown c International Astronomical Union 2018 & T. Prusti, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921317005737 Observations of the satellites of the major planets at Pulkovo Observatory: history and present N. A. Shakht, A. V. Devyatkin, D. L. Gorshanov and M. S. Chubey Central (Pulkovo) Observatory RAS, St- Petersburg 196140, Russia email: [email protected] Abstract. In connection with long on-orbit European space satellite Gaia and the opportunity that now provides ESA, to use the results of observations of the space telescope, we would like to present some results of our long-term observations of the major planets satellites at Pulkovo Observatory. We hope to translate into reality these opportunities, namely the use of new observations and new ephemeris and a practical possibility of a new reduction for modern and old observations. The essential facilities can appear in the space, we give the shortest presentation of space project Orbital Stellar Stereoscopic Observatory. Keywords. natural satellites of great planets, observations, space project OStSO The astrometric positional observations of the major planets and their satellites started almost since the foundation of Pulkovo observatory. The first photographic observations made with Pulkovo Normal Astrograph (PNA) since 1894 yr and continued during one hundred years. Now we have about 6500 plates with the bodies of the Solar System from of total quantity 48 000 plates collected in Pulkovo glass library. The most positions and the list of publications took place in our database www.puldb.ru which is updated. -

Proper Motions and CCD-Photometry of Stars in the Region of the Open Cluster NGC 1513

A&A 396, 125–130 (2002) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021363 & c ESO 2002 Astrophysics Proper motions and CCD-photometry of stars in the region of the open cluster NGC 1513 V. N . F rolov 1, E. G. Jilinski1,2,J.K.Ananjevskaja1,E.V.Poljakov1, N. M. Bronnikova1, and D. L. Gorshanov1 1 The Main Astronomical Observatory, Pulkovo, St. Petersburg, Russia 2 Laborat´orio Nacional de Computa¸c˜ao Cient´ıfica / MCT, Petr´opolis, RJ, Brazil Received 3 July 2002 / Accepted 10 September 2002 Abstract. The results of astrometric and photometric investigations of the poorly studied open cluster NGC 1513 are presented. The proper motions of 333 stars with a root-mean-square error of 1.9masyr−1 were obtained by means of the automated measuring complex “Fantasy”. Eight astrometric plates covering the time interval of 101 years were measured and a total of 141 astrometric cluster members identified. BV CCD-photometry was obtained for stars in an area 17 × 17 centered on the cluster. Altogether 33 stars were considered to be cluster members with high reliability by two criteria. The estimated age of NGC 1513 is 2.54 × 108 years. Key words. open clusters and associations: general – open clusters and associations: individual: NGC 1513 1. Introduction Table 1. Astrometric plates. Plate Exposure Epoch Quality The open cluster NGC 1513 is located in the Perseus constella- (min) tion. Its equatorial and galactic coordinates are: Early epoch A 371 unknown 1899 Nov. 30 good = h m s =+ ◦ = ◦ = − ◦ α 4 09 98 , δ 49 31 ; 152.6, b 1.57 (2000.0). -

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix As Projections of Higher-Dimensional La�Ices in Sco� Joplin’S Music *

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix as Projections of Higher-Dimensional Laices in Sco Joplin’s Music * Joshua W. Hahn NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.2/mto.21.27.2.hahn.php KEYWORDS: meter, rhythm, beat class theory, syncopation, ragtime, poetry, hyperspace, Joplin, Du Bois ABSTRACT: Generated rhythms and the metric matrix can both be modelled by time-domain equivalents to projections of higher-dimensional laices. Sco Joplin’s music is a case study for how these structures can illuminate both musical and philosophical aims. Musically, laice projections show how Joplin creates a sense of multiple beat streams unfolding at once. Philosophically, these structures sonically reinforce a Du Boisian approach to understanding Joplin’s work. Received August 2019 Volume 27, Number 2, June 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory Introduction [1] “Dr. Du Bois, I’ve read and reread your Souls of Black Folk,” writes Julius Monroe Troer, the protagonist of Tyehimba Jess’s 2017 Pulier Prize-winning work of poetry, Olio. “And with this small bundle of voices I hope to repay the debt and become, in some small sense, a fellow traveler along your course” (Jess 2016, 11). Jess’s Julius Monroe Troer is a fictional character inspired by James Monroe Troer (1842–1892), a Black historian who catalogued Black musical accomplishments.(1) In Jess’s narrative, Troer writes to W. E. B. Du Bois to persuade him to help publish composer Sco Joplin’s life story. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

Life Sciences, Physical Sciences, Earth and Environmental Sciences

COLLECTION OVERVIEW LIFE SCIENCES, PHYSICAL SCIENCES, EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES I. SCOPE The life, physical, earth and environmental sciences collections include botany (LC Class QK), biology, natural history, ecology, genetics (LC Class QH), zoology (LC Class QL), human anatomy (LC Class QM), physiology (LC Class QP), microbiology (LC Class QR) astronomy (LC Class QB), physics (LC Class QC), paleontology (LC Class QE), geology (LC Class QE), oceanography (LC Class GC), environmental sciences (LC Class GE), agriculture (LC Class S), medicine (LC Class R), and associated materials classed in bibliography, indexes, and abstracting services (LC Class Z). II. SIZE The Library's collections in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences number 2,145,294 titles. While the Library of Congress has deferred to the National Library of Medicine for the acquisition of clinical medicine since the early 1950s, its collection of medical journals, texts, and monographs exceeds 320,000 titles. For the same period of time, the Library has also deferred acquisition of technical agriculture and the veterinary sciences to the National Agricultural Library, yet the Library holds over 222,294 titles of importance to the Congress and its many constituencies in this subject area. III. GENERAL RESEARCH STRENGTHS The Library's collections in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences are exceptional and, as in the case of the Library's general science and technology collections, have profited greatly from the materials generated by the Smithsonian and copyright deposits. These programs provided and still provide the Library with long, unbroken runs of proceedings, memoirs, monographic series, and journals in the life, physical, earth and environmental sciences. -

Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Wible, James R.; Hoover, Kevin D. Working Paper Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S. Peirce's Engagement with Cournot's Recherches sur les Principes Mathematiques de la Theorie des Richesses CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2013-12 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Wible, James R.; Hoover, Kevin D. (2013) : Mathematical Economics Comes to America: Charles S. Peirce's Engagement with Cournot's Recherches sur les Principes Mathematiques de la Theorie des Richesses, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2013-12, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/149703 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

![Environmental History] Orosz, Joel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6654/environmental-history-orosz-joel-2026654.webp)

Environmental History] Orosz, Joel

Amrys O. Williams Science in America Preliminary Exam Reading List, 2008 Supervised by Gregg Mitman Classics, Overviews, and Syntheses Robert Bruce, The Launching of Modern American Science, 1846-1876 (New York: Knopf, 1987). George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968). ————, Science in American Society (New York: Knopf, 1971). Sally Gregory Kohlstedt and Margaret Rossiter (eds.), Historical Writing on American Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). Ronald L. Numbers and Charles Rosenberg (eds.), The Scientific Enterprise in America: Readings from Isis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). Nathan Reingold, Science, American Style. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991). Charles Rosenberg, No Other Gods: On Science and American Social Thought (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976). Science in the Colonies Joyce Chaplin, Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo- American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). [crosslisted with History of Technology] John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984). Katalin Harkányi, The Natural Sciences and American Scientists in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990). Brooke Hindle, The Pursuit of Science in Revolutionary America, 1735-1789. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956). Judith A. McGaw, Early American Technology: Making and Doing Things from the Colonial Era to 1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1994). [crosslisted with History of Technology] Elizabeth Wagner Reed, American Women in Science Before the Civil War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992). -

The Pulkovo Observatory Library Develops Electronic Services

Library and Information Services in Astronomy IV July 2-5, 2002, Prague, Czech Republic B. Corbin, E. Bryson, and M. Wolf (eds) The Pulkovo Observatory Library Develops Electronic Services Natalia Markova Pulkovo Observatory Library, 65 Pulkovo, 196140 St-Petersburg, Russia [email protected] Abstract. Based on the \Struve Fund", the Pulkovo Observatory lib- rary is working on a new electronic catalogue. The existing printed cata- logue was created in the 19th century and does not reflect the present due to losses incurred during WWII and the fire of 1997. The Pulkovo Observatory library started an electronic catalogue comprised of publications about the institution. This catalogue will in- clude bibliographic descriptions of the literature we house, as well as pictures and photos. We consider placing the catalogue on a web site important because we receive many requests for this type of information from around the world. 1. Introduction The Pulkovo Observatory library needs a new electronic catalogue that will reflect a modern state of funds formed from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries, the period when Wilhelm and Otto Struve were directors. These funds were described in printed catalogs in 1845, 1860 and 1880. Due to the Second World War and a fire in 1997, many parts of the collection were damaged beyond redemption. Thus, the librarians have decided to create an electronic catalog based on subject divisions that will be the most in demand. 2. The Corpus of the Catalog The corpus of the catalog was created in the 1930s and 40s. During this time, jubilee speeches, obituaries, and other materials about the Observatory and its scientific staff were collected.