Big Thorne Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

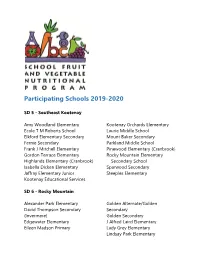

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

RBA Cragg Fonds

Kamloops Museum and Archives R.B.A. Cragg fonds 1989.009, 0.2977, 0.3002, 1965.047 Compiled by Jaimie Fedorak, June 2019 Kamloops Museum and Archives 2019 KAMLOOPS MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES 1989.009, etc. R.B.A. Cragg fonds 1933-1979 Access: Open. Graphic, Textual 2.00 meters Title: R.B.A. Cragg fonds Dates of Creation: 1933-1979 Physical Description: ca. 80 cm of photographs, ca. 40 cm of negatives, ca. 4000 slides, and 1 cm of textual records Biographical Sketch: Richard Balderston Alec Cragg was born on December 5, 1912 in Minatitlan, Mexico while his father worked on a construction contract. In 1919 his family moved to Canada to settle. Cragg gained training as a printer and worked in various towns before being hired by the Kamloops Sentinel in 1944. Cragg worked for the Sentinel until his retirement at age 65, and continued to write a weekly opinion column entitled “By The Way” until shortly before his death. During his time in Kamloops Cragg was active in the Kamloops Museum Association, the International Typographical Union (acting as president on the Kamloops branch for a time), the BPO Elks Lodge Kamloops Branch, and the Rock Club. Cragg was married to Queenie Elizabeth Phillips, with whom he had one daughter (Karen). Richard Balderson Alec Cragg died on January 22, 1981 in Kamloops, B.C. at age 68. Scope and Content: Fonds consists predominantly of photographic materials created by R.B.A. Cragg during his time in Kamloops. Fonds also contains a small amount of textual ephemera collected by Cragg and his wife Queenie, such as ration books and souvenir programs. -

PROVINCI L Li L MUSEUM

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCI_l_Li_L MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY • FOR THE YEAR 1930 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to tbe King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1931. \ . To His Honour JAMES ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Administrator of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1930. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Pt·ovincial Secretary. Pt·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.O., March 26th, 1931. PROVINCIAl. MUSEUM OF NATURAl. HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 26th, 1931. The Ho1Wm·able S. L. Ho11ie, ProvinciaZ Secreta11}, Victo1·ia, B.a. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1930, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE. Staff of the Museum ............................. ------------ --- ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------- 6 Object.. .......... ------------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------------- -- ---------- -- ------------------------ ----- ------------------- 7 Admission .... ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Biutish C0lumma Winter 2000/2001 $5.00 Histoiuc NEWS ISSN 1195-8294 Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation

Volume 34, No. i BIuTIsH C0LuMmA Winter 2000/2001 $5.00 HIsToiuc NEWS ISSN 1195-8294 Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation - r The Canadian Pacific’s Crowsnest Route tram at Cranbrook about 1900. Archival Adventures Remember the smell of coal and steam? The Flood of 1894 Robert Turner, curator emeritus at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, is an authority on the history of railroads and steamships in Yellowhead books on British Columbia and he has written and published a dozen Cedar Cottage BC’s transportation history In this issue he writes about the Crowsnest Route. “Single Tax” Taylor Patricia Theatre Index 2000 British Columbia Historical News British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the P0 Box S254, STATIoN B., VICToRIA BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia Historical Federation A CHARITABLE SOCIETY UNDER THE INCOME TAX ACT Published Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. EDITOR: ExECuTIVE Fred Braches HoNolcsisY PATRON: His HONOUR, THE H0N0ISABLE GARDE B. GARD0M, Q.C. P0 Box 130 HON0eARY PREsIDENT:AuCE GLANvILLE Whonnock BC, V2W 1V9 Box 746 Phone (604) 462-8942 GISAND FORKS, BC VoM aHo brachesnetcom.ca OFFICERs BooK Rrvxrw EDITOR: PREsIDEi’cr:WAYNE DE5R0CHER5 Anne Yandle #2 - 6712 BARER ROAD, DELTA BC 3450 West 20th Avenue V4E 2V3 PHONE (604) 599-4206 (604)507-4202 Vancouver BC, V6S 1E4 FAX. [email protected] FIEsT VICE PRESIDENT: RoJ.V PALLANT Phone (604) 733-6484 1541 MERLYNN CREsCENT. NoRTHVp,NCoUvER 2X9 yandleinterchange. ubc.ca BC V7J PHONE (604) 986-8969 [email protected] SUBscRIPTION SEcRETARY: -

The Cariboo Wagon Road

THE CARIBOO WAGON ROAD he success of the Cariboo goldfields necessitated the further Timprovement of the roads to the Cariboo. In May 1862, Colonel Richard C. Moody advised Governor James Douglas that the Yale to Cariboo route through the Fraser Canyon was the best to adapt for the general development of the country and that it was imperative its construction start at once. The governor concurred and it was decided that the road would be a full 18-feet wide in order to accommodate wagons going and coming from the goldfields and thus it came to be known as the Cariboo Wagon Road. The builders were to be paid large cash subsidies as work progressed and upon completion of their sections were to be granted permission to collect tolls from the travelers for the following 5 years. Captain John Marshall Grant of the Royal Engineers, with a force of sappers, miners, and civilian labor, was to construct the first six miles out of Yale, while Thomas Spence was to extend the road the next seven miles to Chapman’s Bar, at a cost of $47,000. From here, Joseph William Trutch, Spence’s partner, was to tackle the section to a point that would become Boston Bar, a distance of 12 miles, at a cost of $75,000. From here, Spence would continue the road to Lytton. Walter Moberly, a successful engineer, with Charles Oppenheimer, a partner in the great mercantile firm ROYAL ENGINEER'S BUCKLE & BUTTONS. COURTESY WERNER KASCHEL of Oppenheimer Brothers, and Thomas B. Lewis accepted the challenge to build the section from Lytton until the road joined a junction with the wagon road to be built by Gustavus Blin Wright and John Colin Calbreath from Lillooet to Watson’s stopping house. -

BUY BC BUSINESSES Business Buyer's Guide

BUY BC BUSINESSES Business Buyer’s Guide Winter 2013/2014 Southern Interior Region CHANGING THE FACE OF BUSINESS ventureconnect.ca 1.855.421.0082 ntrepreneurs and small businesses are critical to the economic health and prosperity of our communities. From creating and maintaining jobs that Esupport families, to producing goods and services, small business is the engine driving British Columbia’s economy. Small business accounts for 98% of all business in British Columbia Of the 385,900 small businesses operating in the province in 2012, 82% had fewer than five employees In 2012, 26% of BC’s Gross Domestic Product was generated by small business, compared to the national average of 25 percent BC ranks first in the country for the number of small businesses per capita, with 83.5 per 1,000 people 55% of private sector jobs in 2012 were provided by small businesses; second highest in Canada Small business employed over a million people in the province in 2012 Between 2011 and 2012, small business employment in BC grew by 0.4 percent, slightly faster than the national rate of 0.2 percent In 2012, small business provided 31 percent of all wages paid to workers in BC, the highest share of all provinces The accommodation and food services industry was the largest provider of new small business jobs in BC between 2007 and 2012. Employment in this industry climbed 5.2 percent, creating approximately 4,600 new jobs over the five year period One hundred and eighteen Southern Interior business opportunities valued just short of $70 million are represented and offered for sale in this booklet. -

Ancestree Fall Edition 2018) Was Baptized in 18699 in New Westminster; He Would Have Been at Least Forty-Three Years Old When He Married

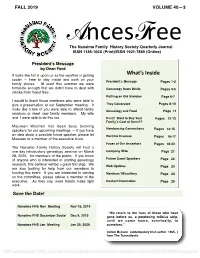

FALL 2019 VOLUME 40—3 !!!AncesTree! ! The Nanaimo Family History Society Quarterly Journal ISSN 1185-166X (Print)/ISSN 1921-7889 (Online) ! President’s Message by Dean Ford It looks like fall is upon us as the weather is getting What’s Inside cooler — time to stay inside and work on your President’s Message Pages 1-2 family stories. At least this summer we were fortunate enough that we didn’t have to deal with Genealogy News Briefs Pages 3-5 smoke from forest fires. Rattling an Old Skeleton Page 6-7 I would to thank those members who were able to give a presentation at our September meeting. It They Celebrated Pages 8-10 looks like a few of you were able to attend family Genealogy and Food Page 11 reunions or meet new family members. My wife and I were able to do this too. Psst!! Want to Buy Your Pages 12-13 Family’s Coat of Arms?? Maureen Wootten has been busy booking Membership Connections speakers for our upcoming meetings — if you have Pages 14-15 an idea about a possible future speaker, please let Wartime Evacuee Pages 16-17 Maureen or a member of the executive know. Faces of Our Ancestors Pages 18-20 The Nanaimo Family History Society will host a one day introductory genealogy seminar on March Company Wife Page 21 28, 2020, for members of the public. If you know of anyone who is interested in starting genealogy Future Guest Speakers Page 22 research, this seminar will be a great first step. We Web Updates Page 23 are also looking for help from our members in hosting this event. -

Mills Hopijy with Strike Finish Terry Sawka, Presldenibf Iodal TERRACE -- the End of the Monday, July 27

Mills hopiJy with strike finish Terry Sawka, presldenibf iodal TERRACE -- The end of the Monday, July 27. non-binding arbitration. The two CPU locals, 1127 and depressed pulp markets. 4, agreed with ~/ils0n!s analysis month-old pulp mill strike last "We'll have to wait and see The two unions, the Canadian 298, at Kitimat's Eurocan pulp "It appears the employers ac- mill were in favour of the pack- of the einployeis':m0tivatidns Friday saw Operations resume at how quickly the pulp mill gets up Paperworkers Union (CPU) and complished what they: wanted during the strti~ei i': : local.mills in Terrace. and going," he said. "Anybody the Pulp and Paperworkers of age by 69 and 79 pei cent respec- through a strike by reduciug their tively, but Mike Wilson, presi- "It was obvi0us:t0 ~us that we "We're quite happy it's over," would be a fool not to say we're Canada (PPWC), had earlier ilwentory and raising the price of would either be forced oi~ strike said Skeena Sawmill manager glad t0 see them back to work," voted 70.2 per cent in favour of dent of local 1127, said there was ,, .. a mixed reaction. Pull" said W!ls°n! : • Or wind up being locked out,,' Don Chesley. Employees at the Woods operation and log :i tile new contract. Ill Prince Rupert members of saidSawka ..... deliveries resumedl Monday .at The package covered three of ,'We're nlad that we've iosta mill came back to work Monday, PPWC local 4 at the Skeena Cel, : "If Rcady's intentions were to concluding a twp-week holiday Skeena Cellulose but the planer : the unions' four demands with month's wages," said Wilson. -

7.0 Fraser River Cultural Heritage Values

Contents Page 1.0 Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 1 2.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Background ...................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Methodology .................................................................................................... 7 5.0 Chronology of Events ....................................................................................... 8 6.0 Natural Heritage Values ................................................................................... 12 6.1 Background .......................................................................................... 12 6.2 Condition of Values Since Nomination .................................................. 12 7.0 Cultural Heritage Values .................................................................................. 37 7.1 Background .......................................................................................... 37 7.2 Condition of Values Since Nomination .................................................. 37 8.0 Recreational Values ......................................................................................... 53 8.1 Background .......................................................................................... 53 8.2 Condition of Values Since Nomination ................................................. -

0 Dec 12 Preface Material (All)

By the Road: Fordism, Automobility, and Landscape Experience in the British Columbia Interior, 1920-1970 by Ben Bradley A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December 2012 © Copyright by Ben Bradley, 2012 By the Road: Fordism, Automobility, and Landscape Experience in the British Columbia Interior, 1920-1970 Ben Bradley Abstract This dissertation examines how popular experiences of nature and history in the British Columbia Interior were structured by automobility – the system of objects, spaces, images, and practices that surrounded private automobiles and public roads. The Fordist state poured massive resources into the provincial road network during the period 1920 to 1970, and in the process created new possibilities for leisure and for profit. Motoring was a new, very modern way of experiencing BC, and also an important economic engine. Making the province’s highways and the landscapes that were visible alongside them look appealing to the motoring public became a matter of concern for many different parties. Boosters, businesses, and tourism promoters who stood to benefit from increased automobile travel often cultivated roadside attractions and lobbied the state to do the same. Starting in the early 1940s, the provincial government established numerous parks along the Interior highway network: the two examined here are Manning and Hamber parks. Beginning in the late 1950s it did the same with historical -

FACTSHEET 2005BCED0003-000029 Ministry of Education Jan

FACTSHEET 2005BCED0003-000029 Ministry of Education Jan. 17, 2005 INTERNET UPGRADES HELP IMPROVE COMPUTER LITERACY • The province will upgrade 422 educational sites from low-speed to high-speed Internet access by March 2005. All upgrades are subject to technical considerations and consultations with school districts. Schools scheduled to be upgraded are listed below. District/College Full Name Site Name Location SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Gordon Terrace Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Highlands Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Junior Alternate Program Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Kootenay Orchards Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Laurie Junior Secondary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Mount Baker Secondary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Parkland Junior Secondary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Pinewood Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Southeast Kootenay School District Office Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Steeples Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay T. M. Roberts Elementary School Cranbrook SD 5 Southeast Kootenay District Learning Centre Fernie SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Fernie Secondary School Fernie SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Isabella Dicken Elementary School Fernie SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Max Turyk Elementary School Fernie SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Southeast Kootenay SD Field Office Fernie SD 5 Southeast Kootenay Jaffray Elementary & Junior Secondary -

Gold Rush Trail CCCTA 2019.Pdf

goldrushtrail.ca 2A2 he Gold Rush Trail is the story of British Columbia, stretching back millennia into prehistory and before. TIt is the story of a mighty river and the lands surrounding it: the cleft between mountains, the carving of canyons, and the fertility of the plains. Gold is not the only treasure found on the trail. The rich history of civilizations, diverse cultures, languages and traditions that came before us also come to life along the way. Here, nature’s abundance beckons to all. Just as many adventurers did before us, travellers come seeking the{ riches of our region. The Gold Rush Trail begins at the mouth of the Fraser River in New{ Westminster and winds its way north to Barkerville Historic Town & Park, following the traditional Indigenous peoples’ trading routes utilized during the fur trade and expanded during the gold rushes of 1858-1862. Today’s Gold Rush Trail is an experiential corridor, a journey of stories, peoples, Centuries of travellers have felt the activities and places that we share with “ pull of BC’s Gold Rush Trail. From our visitors. Just as many adventurers yesteryear’s arduous weeks-long trek did before us, travellers come seeking the promising untold riches to today’s riches of our region. stunning three-day road trip, it has long “ Travelling this historic trail, you’ll have a been a beautiful and varied journey, rich chance to disconnect, get away from the in history, with a lot to see and experience crowds and truly connect with history, along the way. Indigenous culture and nature.