Do-It-Yourself Wills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: the Dawn of the Electronic Will

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 42 2008 Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will Joseph Karl Grant Capital University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph K. Grant, Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will, 42 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 105 (2008). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol42/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHATTERING AND MOVING BEYOND THE GUTENBERG PARADIGM: THE DAWN OF THE ELECTRONIC WILL Joseph Karl Grant* INTRODUCTION Picture yourself watching a movie. In the film, a group of four siblings are dressed in dark suits and dresses. The siblings, Bill Jones, Robert Jones, Margaret Jones and Sally Johnson, have just returned from their elderly mother's funeral. They sit quietly in their mother's attorney's office intently watching and listening to a videotape their mother, Ms. Vivian Jones, made before her death. On the videotape, Ms. Jones expresses her last will and testament. Ms. Jones clearly states that she would like her sizable real estate holdings to be divided equally among her four children and her valuable blue-chip stock investments to be used to pay for her grandchildren's education. -

Types of Wills Alexandra Gadzo (Palo Alto, California)

CHAPTER 10 Types of Wills ALEXANDRA GADZO (Palo Alto, Calforna) will is used to designate how, when, and to whom your assets will pass at your death. In addition to Anaming an Executor or Executrix (sometimes called a Personal Representative) to collect and distribute your assets, your will is the document in which you name guardians for your minor children. If you have a living trust, a pour over will is generally used so that at your death, the will “pours” any assets not in your living trust into the trust so the assets can be distributed according to the trust’s terms. There may or may not need to be a probate first depending on the amount of the assets. REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL You can draft a typewritten will or have an attorney draft a will for you. In California, the requirements for a will to be legally effective are as follows: • the testator must be 18 years or older; • the testator must be of sound mind; • the document must state that it is a will; • it must be type-written or created and printed using a computer; • you need to appoint at least one executor; • the will must provide for the disposition of your assets; • the will must be signed and have a date of execution; and • two witnesses who are at least 18 years of age must be present when the testator signs the will. These witnesses must also be of sound mind and understand they are witnesses for your will. The witnesses may not be beneficiaries of the will, and the witnesses must see the testator and the other witness sign your will. -

Case and ~C®Mment

251 CASE AND ~C®MMENT. CROWN -SERVANT- INCORPORATION -IMMUNITY FROM BEING SUED. The recent case of Gilleghan v. Minister of Healthl decided by Farwell, J., is a decision on the questions : Will an action lie against a Minister-of the Crown in respect of an act admittedly done as a Minister of the Crown? Or -is the true view that the only remedy is against the Crown by petition of right? Does the mere incorporation. of a servant of the Crown confer the privilege of suing and the liability to be sued? The rationale for the general rule that a servant of the Crown cannot be sued in his official capacity is that the servant holds no assets in his official capacity which can be seized in satisfaction of a judgment. He holds only on behalf of the Crown.2 Collins, M.R., in Bainbridge v. Postmaster-General3 said : "The revenue of the country cannot be reached by an action against an official, unless there is some provision to be found in the legisla~ tion to enable this to be done." In the Gilleghan case the defendant moved to-strike out the statement of claim. The Minister of Health was established by the Ministry of Health Act- which provided, inter alia, that the Minister "may sue and be sued in the name of the Minister of Health" and that "for the purpose of acquiring and holding land" the Minister for the time being "shall be a corporation sole." Farwell, J ., decided that the provision that the Minister may sue and be sued does not give the plaintiff a cause of action for breach of contract against the Minister. -

The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2019 The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act Barry Cushman Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation Barry Cushman, The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act, 54 Real Prop., Tr. & Est. L.J. 243 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/1416 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DECLINE OF REVOCATION BY PHYSICAL ACT Barry Cushman* Author's Synopsis: The power to revoke one's will by physical act was enshrined in Anglo-American law in 1677 by the Statute of Frauds. It remains the law in Great Britain, in such developed Commonwealth countries as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and in each state of the United States ofAmerica. Yet the revocation of wills by physical act has become badly out of phase with the law governing nonprobate transfers, which as a general matter requires that an instrument of transfer be revoked only by a writing signed by the transferor. This Article surveys the place of revocation by physical act in the law governing will substitutes, such as payable-on-death designations on bank accounts, transfer-on-deathdesignations on brokerage accounts, life insurance and annuities, beneficiary deeds, and revocable trusts. -

Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Louisiana Law Review Volume 80 Number 4 Summer 2020 Article 9 11-11-2020 Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Ronald J. Scalise Jr., Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, 80 La. L. Rev. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol80/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 1332 I. A (Very Brief) History of Wills in the United States ................. 1333 A. Functions of Form Requirements ........................................ 1335 B. The Law of Yesterday: The Development of Louisiana’s Will Forms ....................................................... 1337 II. Compliance with Formalities ..................................................... 1343 A. The Slow Migration from “Strict Compliance” to “Substantial Compliance” to “Harmless Error” in the United States .............................................................. 1344 B. Compliance in Other Jurisdictions, Civil and Common .............................................................. -

Wills and Trusts (4Thed

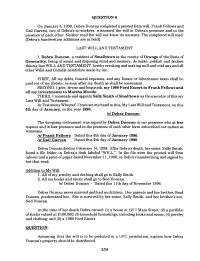

QUESTION 6 On January 5, 1990, Debra Duncan completed a printed form will. Frank Fellows and Gail Garven, two of Debra's co-workers, witnessed the will in Debra's presence and in the presence of each other. Neither read the will nor knew its contents. The completed will read: [Debra's handwritten additions are in bold] LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT I, Debra Duncan, a resident of Smalltown in the county of Orange of the State of Generality, being of sound and dsposing mind and memory, do make, publish and declare this my last WILL AND TESTAMENT, hereby revoking and making null and void any and all other Wills and Codicils heretofore made by me. FIRST, All my debts, funeral expenses, and any Estate or Inheritance taxes shall be paid out of my Estate, as soon after my death as shall be convenient. SECOND, I give, devise and bequeath, my 1989 Ford Escort to Frank Fellows and all my investments to Martha Murdo. THIRD, I nominate and appoint Sally Smith of Smalltown as the executor of this my Last Wlll and Testament. In Testimony Whereof, I have set my hand to this, My Last Will andTestarnent, on this 5th day of January, in the year 1990. IS/ Debra Duncan The foregoing instrument was signed by Debra Duncan in our presence who at her request and in her presence and in the presence of each other have subscribed our names as witnesses. Is/ Frank Fellows Dated this 5th day of January 1990. Is1 Gail Garven Dated this 5th day of January 1990. -

STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, NA 300

THE ANATOMY OF A WILL: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN WILL DRAFTING* Authors: STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, N.A. 300 Crescent Court, Suite 800 Dallas, Texas 75201 BERNARD E. JONES Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 Houston, Texas 77027 R. J. WATTS, II Law Office of R. J. Watts, II 9400 N. Central Expressway, Ste. 306 Dallas, Texas 75231-5039 State Bar of Texas ESTATE PLANNING AND PROBATE 101 COURSE June 25, 2012 San Antonio CHAPTER 2.1 * Copyright © 1993 - 2011 * by Steve R. Akers Anatomy of A Will Chapter 2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1. NUTSHELL OF SUBSTANTIVE LAW REGARDING VALIDITY OF A WILL................................................................. 1 I. FUNDAMENTAL REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL. 1 A. What Is a "Will"?. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Origin of the Term "Last Will and Testament".. 1 3. Summary of Basic Requirements. 1 B. Testamentary Intent. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Instrument Clearly Labeled as a Will.. 2 3. Models or Instruction Letters. 2 4. Extraneous Evidence of Testamentary Intent.. 2 C. Testamentary Capacity - Who Can Make a Will. 2 1. Statutory Provision. 2 2. Judicial Development of the "Sound Mind" Requirement.. 2 a. Five Part Test--Current Rule.. 2 b. Old Four Part Test--No Longer the Law.. 2 c. Lucid Intervals. 3 d. Lay Opinion Testimony Admissible.. 3 e. Prior Adjudication of Insanity--Presumption of Continued Insanity. 3 f. Subsequent Adjudication of Insanity--Not Admissible. 3 g. Comparison of Testamentary Capacity with Contractual Capacity. 4 (1) Contractual Capacity in General.. 4 (2) Testamentary and Contractual Capacity Compared. 4 h. Insane Delusion. -

The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness

California Western Law Review Volume 20 Number 2 Article 4 1-1-1984 The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness Robert P. Kirk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr Recommended Citation Kirk, Robert P. (1984) "The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness," California Western Law Review: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol20/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Western Law Review by an authorized editor of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kirk: The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefu +(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: 20 Cal. W. L. Rev. 258 1983-1984 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Wed Sep 28 15:29:58 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2016 1 California Western Law Review, Vol. 20 [2016], No. 2, Art. 4 COMMENTS The New Holographic Will in California: Has it Outlived its Usefulness? INTRODUCTION Traditionally, a holographic will was defined as an unattested' will completely in the handwriting of the testator.2 Presently, a minority of states permit their use.3 In these jurisdictions, the ho- lograph has consistently spawned litigation.4 In California, early courts looked upon the holograph with dis- favor. -

Failure of Gifts by Will

Failure of Gifts by Will This month’s CPD will examine the many reasons why a gift made by Will may fail. This paper will look at the most common reasons for the failure of gifts, listed below, but practitioner’s should be aware that this list is non-exhaustive and gifts may fail for other reasons; including a contingency for a gift not being met, as a matter of public policy, or even because a condition attached to a gift is void. MAIN REASONS A GIFT MAY FAIL A gift may fail for one of the following main reasons: The beneficiary or a spouse or civil partner of the beneficiary is an attesting witness The divorce or dissolution of a marriage or civil partnership between the testator and the beneficiary Lapse Ademption Abatement Uncertainty The beneficiary is guilty of the unlawful killing of the testator The beneficiary disclaims their gift BENEFICIARY OR THEIR SPOUSE IS AN ATTESTING WITNESS This is the most well-known reason for the failure of a gift. Section 15 of the Wills Act 1837 deprives an attesting witness and their spouse or civil partner from receiving any benefit under the Will which they attest. If a beneficiary or their spouse is an attesting witness the attestation itself will be valid and this will not cause the Will to fail; only the gift to the witness or their spouse shall be void. There are some key exceptions to this general rule: If a beneficiary was not married to the witness at the time the attestation took place but married the witness afterwards then they will not be deprived of their benefit. -

The Posse Comitatus and the Office of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned to the Aid of Law Enforcement

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 104 Article 3 Issue 4 Symposium On Guns In America Fall 2015 The oP sse Comitatus And The Office Of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement David B. Kopel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation David B. Kopel, The Posse Comitatus And The Office Of erSh iff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement, 104 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 761 (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol104/iss4/3 This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/15/10404-0761 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 104, No. 4 Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE POSSE COMITATUS AND THE OFFICE OF SHERIFF: ARMED CITIZENS SUMMONED TO THE AID OF LAW ENFORCEMENT DAVID B. KOPEL* Posse comitatus is the legal power of sheriffs and other officials to summon armed citizens to aid in keeping the peace. The posse comitatus can be traced back at least as far as the reign of Alfred the Great in ninth- century England. The institution thrives today in the United States; a study of Colorado finds many county sheriffs have active posses. Like the law of the posse comitatus, the law of the office of sheriff has been remarkably stable for over a millennium. -

Introduction to Will Drafting for Accountants

Introduction to Will Drafting for Accountants MONDAY, 25 MARCH 2019 In association with… icaew.com The value of ICAEW membership Qualified professionals to advise you on technical and 1 ethical matters 259 World class Industry and library ... country guides ... with Connecting information ACA/FCA members through and research online professionals communities, offering blogs and forums tailored help Internationally recognised designatory letters Member App available on Android and iOS INTELLIGENCE AND INSIGHT APRIL 2015 | ICAEW.COM/ECONOMIA ISSUE 37 | ACCOUNTANCY | FINANCE | BUSINESS 200+ Confidential Fight for and non- your right Specialist technical Multimillionaire barrow boy Barry Hearn on fortune, family and making his own way helpsheets and judgmental PRIVATE EQUITY THE PENSIONS REVOLUTION EUROPEAN support and ROAD TRIPS FAQs advice 18 International member groups 3,450+ 24h electronic 24 10 journals UK District International Societies offices and books Information online when you need it – no cost, no time zone, no delay Agenda Time Session 09:00 Registration 09:30 Formal requirement for wills; When to use life interest trusts; When to use discretionary trusts; Taking instructions for a will – who is the client?, family, size of estate, who does the client wish to benefit; Capacity to make a will and knowledge and approval of the contents; Undue influence: Conflict of interest – couples may have different wishes; Does client have an equitable interest in a house vested in the name of someone else? Does someone else have an equitable -

The History of Bail and Pretrial Release

1 The hisTory of Bail and PreTrial release septemBer 23, 2010 TimoThy r. schnacke, michael r. Jones, claire m. B. Brooker the History of Bail And 1 Pretrial release1 A. IntroductIon1 cases alleging abuses in the pretrial release or detention decision-making process. These abus- While the notion of bail has been traced to an- es were originally often linked to the inability to cient Rome,2 the American understanding of bail predict trial outcome, and later to the inability is derived from 1,000-year-old English roots. A to adequately predict court appearance and the study of this “modern” history of bail reveals two commission of new crimes. This, in turn, led to fundamental themes. First, as noted in June Car- an over-reliance on judicial discretion to grant or bone’s comprehensive study of the topic, “[b]ail deny a bail bond and the fixing of some money [originally] reflected the judicial officer’s predic- amount (or other condition of pretrial release) tion of trial outcome.”3 In fact, bail bond decisions that presumably helped mitigate a defendant’s are all about prediction, albeit today about the pretrial misconduct. Accordingly, the follow- prediction of a defendant’s probability of making ing history of bail suggests that as our ability to all court appearances and not committing any predict a defendant’s pretrial conduct becomes new crimes. The science of accurately predicting more accurate, our need for reforming how bail a defendant’s pretrial conduct, and misconduct, is administered will initially be great, and then has only emerged over the past few decades, should diminish over time.