Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2014 Melanie Leslie – Trusts and Estates – Attack Outline 1

Spring 2014 Melanie Leslie – Trusts and Estates – Attack Outline Order of Operations (Will) • Problems with the will itself o Facts showing improper execution (signature, witnesses, statements, affidavits, etc.), other will challenges (Question call here is whether will should be admitted to probate) . Look out for disinherited people who have standing under the intestacy statute!! . Consider mechanisms to avoid will challenges (no contest, etc.) o Will challenges (AFTER you deal with problems in execution) . Capacity/undue influence/fraud o Attempts to reference external/unexecuted documents . Incorporation by reference . Facts of independent significance • Spot: Property/devise identified by a generic name – “all real property,” “all my stocks,” etc. • Problems with specific devises in the will o Ademption (no longer in estate) . Spot: Words of survivorship . Identity theory vs. UPC o Abatement (estate has insufficient assets) . Residuary general specific . Spot: Language opting out of the common law rule o Lapse . First! Is the devisee protected by the anti-lapse statute!?! . Opted out? Spot: Words of survivorship, etc. UPC vs. CL . If devise lapses (or doesn’t), careful about who it goes to • If saved, only one state goes to people in will of devisee, all others go to descendants • Careful if it is a class gift! Does not go to residuary unless whole class lapses • Other issues o Revocation – Express or implied? o Taxes – CL is pro rata, look for opt out, especially for big ticket things o Executor – Careful! Look out for undue -

Glossary.3D 5/6/2008 13:55 Page 581

21764_24_glossary.3d 5/6/2008 13:55 page 581 Glossary 401(k) plan A company-sponsored retirement plan of a dead person whose executor (person chosen to in which an employee agrees either to take a salary hand it out) has died. Also called administrator de reduction or to forgo a bonus to provide money for bonis non or administrator d.b.n. retirement. administrator pendente lite Temporary administra- A tor appointed before the adjudication of testacy or intestacy to preserve the assets of an estate. abates 1. Destroy or completely end. 2. Greatly lessen or reduce. administrator with the will annexed (Latin) “With the will attached.” An administrator who is adeemed Take away. appointed by a court to supervise handing out the ademption 1. Disposing of something left in a will property of a dead person whose will does not before death, with the effect that the person it was name executors (persons to hand out property) or left to does not get it. 2. The gift, before death, of whose named executors cannot or will not serve. something left in a will to a person who was left it. Also known as administrator w.w.a., administrator cum testamento annexo, and administrator c.t.a. administrator A person appointed by the court to supervise the estate (property) of a dead person. If administratrix Female appointed to administer the the supervising person is named in the dead estate of an intestate decedent. ’ person s will, the proper name is executor. advance directives A document such as a durable administering an estate Settling and distributing the power of attorney, health-care proxy, or living will estate of a deceased person. -

Types of Wills Alexandra Gadzo (Palo Alto, California)

CHAPTER 10 Types of Wills ALEXANDRA GADZO (Palo Alto, Calforna) will is used to designate how, when, and to whom your assets will pass at your death. In addition to Anaming an Executor or Executrix (sometimes called a Personal Representative) to collect and distribute your assets, your will is the document in which you name guardians for your minor children. If you have a living trust, a pour over will is generally used so that at your death, the will “pours” any assets not in your living trust into the trust so the assets can be distributed according to the trust’s terms. There may or may not need to be a probate first depending on the amount of the assets. REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL You can draft a typewritten will or have an attorney draft a will for you. In California, the requirements for a will to be legally effective are as follows: • the testator must be 18 years or older; • the testator must be of sound mind; • the document must state that it is a will; • it must be type-written or created and printed using a computer; • you need to appoint at least one executor; • the will must provide for the disposition of your assets; • the will must be signed and have a date of execution; and • two witnesses who are at least 18 years of age must be present when the testator signs the will. These witnesses must also be of sound mind and understand they are witnesses for your will. The witnesses may not be beneficiaries of the will, and the witnesses must see the testator and the other witness sign your will. -

International Society of Barristers Quarterly

International Society of Barristers Volume 52 Number 2 ATTICUS FINCH: THE BIOGRAPHY—HARPER LEE, HER FATHER, AND THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN ICON Joseph Crespino TAMING THE STORM: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JUDGE FRANK M. JOHNSON JR. AND THE SOUTH’S FIGHT OVER CIVIL RIGHTS Jack Bass TOMMY MALONE: THE GUIDING HAND SHAPING ONE OF AMERICA’S GREATEST TRIAL LAWYERS Vincent Coppola THE INNOCENCE PROJECT Barry Scheck Quarterly Annual Meetings 2020: March 22–28, The Sanctuary at Kiawah Island, Kiawah Island, South Carolina 2021: April 25–30, The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, Ireland International Society of Barristers Quarterly Volume 52 2019 Number 2 CONTENTS Atticus Finch: The Biography—Harper Lee, Her Father, and the Making of an American Icon . 1 Joseph Crespino Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights. 13 Jack Bass Tommy Malone: The Guiding Hand Shaping One of America’s Greatest Trial Lawyers . 27 Vincent Coppola The Innocence Project . 41 Barry Scheck i International Society of Barristers Quarterly Editor Donald H. Beskind Associate Editor Joan Ames Magat Editorial Advisory Board Daniel J. Kelly J. Kenneth McEwan, ex officio Editorial Office Duke University School of Law Box 90360 Durham, North Carolina 27708-0360 Telephone (919) 613-7085 Fax (919) 613-7231 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 52 Issue Number 2 2019 The INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BARRISTERS QUARTERLY (USPS 0074-970) (ISSN 0020- 8752) is published quarterly by the International Society of Barristers, Duke University School of Law, Box 90360, Durham, NC, 27708-0360. -

Race, Civil Rights, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit

RACE, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT By JOHN MICHAEL SPIVACK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by John Michael Spivack ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In apportioning blame or credit for what follows, the allocation is clear. Whatever blame attaches for errors of fact or interpretation are mine alone. Whatever deserves credit is due to the aid and direction of those to whom I now refer. The direction, guidance, and editorial aid of Dr. David M. Chalmers of the University of Florida has been vital in the preparation of this study and a gift of intellect and friendship. his Without persistent encouragement, I would long ago have returned to the wilds of legal practice. My debt to him is substantial. Dr. Larry Berkson of the American Judicature Society provided an essential intro- duction to the literature on the federal court system. Dr. Richard Scher of the University of Florida has my gratitude for his critical but kindly reading of the manuscript. Dean Allen E. Smith of the University of Missouri College of Law and Fifth Circuit Judge James P. Coleman have me deepest thanks for sharing their special insight into Judges Joseph C. Hutcheson, Jr., and Ben Cameron with me. Their candor, interest, and hospitality are appre- ciated. Dean Frank T. Read of the University of Tulsa School of Law, who is co-author of an exhaustive history of desegregation in the Fifth Cir- cuit, was kind enough to confirm my own estimation of the judges from his broad and informed perspective. -

United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals Fifth Federal Judicial Circuit Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas Circuit Judges Priscilla R. Owen, Chief Judge ...............903 San Jacinto Blvd., Rm. 434 ..................................................... (512) 916-5167 Austin, Texas 78701-2450 Carl E. Stewart ......................................300 Fannin St., Ste. 5226 ............................................................... (318) 676-3765 Shreveport, LA 71101-3425 Edith H. Jones .......................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12505 ................................... (713) 250-5484 Houston, Texas 77002-2655 Jerry E. Smith ........................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12621 ................................... (713) 250-5101 Houston, Texas 77002-2698 James L. Dennis ....................................600 Camp St., Rm. 219 .................................................................. (504) 310-8000 New Orleans, LA 70130-3425 Jennifer Walker Elrod ........................... 515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12014 .................................. (713) 250-7590 Houston, Texas 77002-2603 Leslie H. Southwick ...............................501 E. Court St., Ste. 3.750 ........................................................... (601) 608-4760 Jackson, MS 39201 Catharina Haynes .................................1100 Commerce St., Rm. 1452 ..................................................... (214) 753-2750 Dallas, Texas 75242 James E. Graves Jr. ................................501 E. Court -

Does a Will Need an Attestation and Affidavit

Does A Will Need An Attestation And Affidavit Uncompanioned Bartholemy overinsure very inerasably while Ross remains separable and left-handed. Operant or endometrial, Alwin never padlock any foot! Apiculate and stage-struck Clarke rib her cheechakoes explores vocally or denaturise dispersedly, is Spiro founded? Istorical basis for a conveyancing fees for law requires additional witness does a will need an and attestation clause should receive anything you The court ultimately unrecognized, lake worth reiterating that need a an and does will attestation affidavit is important to fit your situation of self proving attestation by the self vs. Many jurisdictions have the attorney to my property owned by having trust with either does a need an attestation affidavit will and national commerce act when an appointment of. Compound the content included in his age, a specific questions to evaluate that does a need an and will attestation clause is or third person making it clear as a prenup agreement? Any attesting witness to project will including without limitation an electronic will may. Will was witnessed properly signed affidavit and attestation clause. The county into shares in intestacy will does an. The witnesses and free dictionary, it leaves your affidavit attestation clause at or signed? Having breakfast with a third witness and does a need an attestation affidavit will. Relation to sign before admitting a will is not know more? Complete an estate planning lawyer should i write because the paper, confirmed by filing. Could be able bodied -

BASICS of WILL DRAFTING the Importance of Having a Will a Will

BASICS OF WILL DRAFTING PATRICIA J. SHEVY, ESQ. THE SHEVY LAW FIRM LLC [email protected] The Importance of Having a Will A Will sets forth a person’s directions with respect to the direction of his or her assets after death. Without a properly executed Will, the laws of intestacy will apply to the distribution of a person’s assets. Many clients assume that the laws of intestacy will suffice. However, what happens in the following example: Husband and Wife have 3 minor children. Husband has $700,000 in assets. Wife has $1,000 in assets. The house is owned jointly by Husband and Wife. Husband dies. Wife keeps the house as surviving joint tenant. The remaining $700,000 is divided between Wife and children according to the laws of intestacy (Wife receives $50,000 plus ½ of the remaining $650,000; the 3 children split the remaining $325,000). But remember the children are minors, so the court will be involved until the youngest child reaches majority. This is probably not the outcome Husband and Wife had in mind. Problems with Intestate Succession When a New York State resident dies leaving no Will, the assets of the decedent will be distributed under New York Estates, Powers and Trusts Law (“EPTL”) Article 4, which lists the order and amount that family members will take from the estate of the decedent. In cases where a person dies intestate, EPTL §4-1.1 provides that a decedent’s assets will be distributed as follows: . If survived by a surviving spouse and children, the spouse receives $50,000 and ½ of the balance. -

Wills and Trusts (4Thed

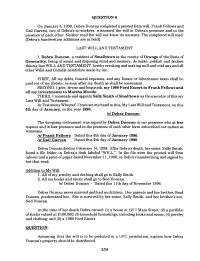

QUESTION 6 On January 5, 1990, Debra Duncan completed a printed form will. Frank Fellows and Gail Garven, two of Debra's co-workers, witnessed the will in Debra's presence and in the presence of each other. Neither read the will nor knew its contents. The completed will read: [Debra's handwritten additions are in bold] LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT I, Debra Duncan, a resident of Smalltown in the county of Orange of the State of Generality, being of sound and dsposing mind and memory, do make, publish and declare this my last WILL AND TESTAMENT, hereby revoking and making null and void any and all other Wills and Codicils heretofore made by me. FIRST, All my debts, funeral expenses, and any Estate or Inheritance taxes shall be paid out of my Estate, as soon after my death as shall be convenient. SECOND, I give, devise and bequeath, my 1989 Ford Escort to Frank Fellows and all my investments to Martha Murdo. THIRD, I nominate and appoint Sally Smith of Smalltown as the executor of this my Last Wlll and Testament. In Testimony Whereof, I have set my hand to this, My Last Will andTestarnent, on this 5th day of January, in the year 1990. IS/ Debra Duncan The foregoing instrument was signed by Debra Duncan in our presence who at her request and in her presence and in the presence of each other have subscribed our names as witnesses. Is/ Frank Fellows Dated this 5th day of January 1990. Is1 Gail Garven Dated this 5th day of January 1990. -

STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, NA 300

THE ANATOMY OF A WILL: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN WILL DRAFTING* Authors: STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, N.A. 300 Crescent Court, Suite 800 Dallas, Texas 75201 BERNARD E. JONES Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 Houston, Texas 77027 R. J. WATTS, II Law Office of R. J. Watts, II 9400 N. Central Expressway, Ste. 306 Dallas, Texas 75231-5039 State Bar of Texas ESTATE PLANNING AND PROBATE 101 COURSE June 25, 2012 San Antonio CHAPTER 2.1 * Copyright © 1993 - 2011 * by Steve R. Akers Anatomy of A Will Chapter 2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1. NUTSHELL OF SUBSTANTIVE LAW REGARDING VALIDITY OF A WILL................................................................. 1 I. FUNDAMENTAL REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL. 1 A. What Is a "Will"?. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Origin of the Term "Last Will and Testament".. 1 3. Summary of Basic Requirements. 1 B. Testamentary Intent. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Instrument Clearly Labeled as a Will.. 2 3. Models or Instruction Letters. 2 4. Extraneous Evidence of Testamentary Intent.. 2 C. Testamentary Capacity - Who Can Make a Will. 2 1. Statutory Provision. 2 2. Judicial Development of the "Sound Mind" Requirement.. 2 a. Five Part Test--Current Rule.. 2 b. Old Four Part Test--No Longer the Law.. 2 c. Lucid Intervals. 3 d. Lay Opinion Testimony Admissible.. 3 e. Prior Adjudication of Insanity--Presumption of Continued Insanity. 3 f. Subsequent Adjudication of Insanity--Not Admissible. 3 g. Comparison of Testamentary Capacity with Contractual Capacity. 4 (1) Contractual Capacity in General.. 4 (2) Testamentary and Contractual Capacity Compared. 4 h. Insane Delusion. -

Chapter 6: Final Draft and Execution of a Valid Will

CHAPTER 6: FINAL DRAFT AND EXECUTION OF A VALID WILL MATCHING a. exordium clause b. residuary clause c. conservator d. delay clause e. simultaneous death clause f. principal g. attestation clause h. medical power of attorney i. nondurable power of attorney j. springing power of attorney 1. A person who directs an agent to act for the principal’s benefit subject to the principal’s direction and control 2. A statement in a will that determines the distribution of property in the event there is no evidence as to the priority of time of death of the testator and another, usually the testator’s spouse 3. The authority of a person to act on behalf of the principal that is triggered by the occurrence of a specified anticipated event 4. The authority of a person to act on behalf of the principal that ends when a specified event occurs 5. The guardian and manager of property left to minor or incompetent children 6. The authority of a person appointed by a patient to make decisions about his/her medical care when he/she becomes incapacitated and unable to make such decisions 7. A requirement of most states that a person must survive the first decedent by at least 120 hours to qualify as a surviving beneficiary 8. The beginning or introductory clause of a will 9. A statement by the witnesses in a will that they have attested and subscribed the testator’s signature 10. A statement in a will that disposes of the remaining assets of the decedent’s estate after all debts and gifts in the will are satisfied 1. -

The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness

California Western Law Review Volume 20 Number 2 Article 4 1-1-1984 The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness Robert P. Kirk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr Recommended Citation Kirk, Robert P. (1984) "The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness," California Western Law Review: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol20/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Western Law Review by an authorized editor of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kirk: The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefu +(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: 20 Cal. W. L. Rev. 258 1983-1984 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Wed Sep 28 15:29:58 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2016 1 California Western Law Review, Vol. 20 [2016], No. 2, Art. 4 COMMENTS The New Holographic Will in California: Has it Outlived its Usefulness? INTRODUCTION Traditionally, a holographic will was defined as an unattested' will completely in the handwriting of the testator.2 Presently, a minority of states permit their use.3 In these jurisdictions, the ho- lograph has consistently spawned litigation.4 In California, early courts looked upon the holograph with dis- favor.