International Society of Barristers Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H. Res. 1525 in the House of Representatives

H. Res. 1525 In the House of Representatives, U. S., July 26, 2010. Whereas Nelle Harper Lee was born on April 28, 1926, to Amasa Coleman Lee and Frances Finch in Monroeville, Alabama; Whereas Nelle Harper Lee wrote the novel ‘‘To Kill a Mock- ingbird’’ portraying life in the 1930s in the fictional small southern town of Maycomb, Alabama, which was modeled on Ms. Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama; Whereas ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’ addressed the issue of ra- cial inequality in the United States by revealing the hu- manity of a community grappling with moral conflict; Whereas ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’ was first published in 1960 and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1961; Whereas ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’ was the basis for the 1962 Oscar-winning film of the same name starring Gregory Peck; Whereas ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’ is one of the great Amer- ican novels of the 20th century, having been published in more than 40 languages and having sold over 30 million copies; Whereas in 2007, Nelle Harper Lee was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters; 2 Whereas in 2007, President George W. Bush awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Nelle Harper Lee for her great contributions to literature and observed ‘‘ ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ has influenced the character of our country for the better’’ and ‘‘As a model of good writing and humane sensibility, this book will be read and stud- ied forever’’; and Whereas ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’ is celebrated each year in Monroeville, Alabama, through annual public perform- ances featuring local amateur actors: Now, therefore, be it Resolved, That the House of Representatives— (1) recognizes the historic milestone of the 50th an- niversary of the publication of ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’; and (2) honors Nelle Harper Lee for her outstanding achievement in the field of American literature in au- thoring ‘‘To Kill a Mockingbird’’. -

“Strom Thurmond's America”

“Strom Thurmond’s America” Joseph Crespino, Emory University Summersell Lecture Series Alright, good afternoon. I’m going to go ahead and get started. My name is Josh Rothman. I direct the Francis Summersell Center for the Study of the South, which is the sponsor of tonight’s event. It gives me really great pleasure to introduce our speaker this afternoon, Joseph Crespino. He’s currently Professor of History at Emory University. Crespino was born and raised in Mississippi, attended college at Northwestern University, acquired (and I just discovered this today), a master’s in education from the University of Mississippi, and took his PhD in history at Stanford University in 2002. Since receiving his degree, he’s become, I think it’s fair to say, one of his generation’s leading scholars in the postwar political history, bringing special attention to bear on his native south. His first book In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution was published in 2007. It makes a provocative argument that as whites in Mississippi reluctantly accommodated themselves to the changes in the Civil Rights Era, they linked their resistance to a broader conservative movement in the United States and thus made their own politics a vital component of what would become the modern Republican south. In Search of Another Country won multiple prizes, including the Lillian Smith Book Award from the Southern Regional Council, the McLemore Prize for the best book on Mississippi history from the Mississippi Historical Society, and the Non-fiction Prize from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters. -

(Nelle) Harper Lee WRITINGS by the AUTHOR

(Nelle) Harper Lee American Novelists Since World War II: Second Series (Nelle) Harper Lee Dorothy Jewell Altman (Bergen College) Born: April 28, 1926 in Monroeville, Alabama, United States Died: February 19, 2016 in Monroeville, Alabama, United States Other Names : Lee, Nelle Harper Nationality: American Occupation: Novelist American Novelists Since World War II: Second Series. Ed. James E. Kibler. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 6 . Detroit: Gale, 1980. From Literature Resource Center . Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1980 Gale Research, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning Table of Contents: Biographical and Critical Essay To Kill a Mockingbird Writings by the Author Further Readings about the Author WORKS: WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR: Book To Kill a Mockingbird (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1960; London: Heinemann, 1960). Periodical Publications "Love--In Other Words," Vogue , 137 (15 April 1961): 64-65. "Christmas to Me," McCalls , 89 (December 1961): 63. BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY: Harper Lee's reputation as an author rests on her only novel, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). An enormous popular success, the book was selected for distribution by the Literary Guild and the Book-of-the-Month Club and was published in a shortened version as a Reader's Digest condensed book. It was also made into an Academy Award-winning film in 1962. Moreover, the novel was critically acclaimed, winning among other awards the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (1961), the Brotherhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (1961), and the Bestsellers magazine's Paperback of the Year Award (1962). Although Lee stresses that To Kill a Mockingbird is not autobiographical, she allows that a writer "should write about what he knows and write truthfully." The time period and setting of the novel obviously originate in the author's experience as the youngest of three children born to lawyer Amasa Coleman Lee (related to Robert E. -

Race, Civil Rights, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit

RACE, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT By JOHN MICHAEL SPIVACK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by John Michael Spivack ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In apportioning blame or credit for what follows, the allocation is clear. Whatever blame attaches for errors of fact or interpretation are mine alone. Whatever deserves credit is due to the aid and direction of those to whom I now refer. The direction, guidance, and editorial aid of Dr. David M. Chalmers of the University of Florida has been vital in the preparation of this study and a gift of intellect and friendship. his Without persistent encouragement, I would long ago have returned to the wilds of legal practice. My debt to him is substantial. Dr. Larry Berkson of the American Judicature Society provided an essential intro- duction to the literature on the federal court system. Dr. Richard Scher of the University of Florida has my gratitude for his critical but kindly reading of the manuscript. Dean Allen E. Smith of the University of Missouri College of Law and Fifth Circuit Judge James P. Coleman have me deepest thanks for sharing their special insight into Judges Joseph C. Hutcheson, Jr., and Ben Cameron with me. Their candor, interest, and hospitality are appre- ciated. Dean Frank T. Read of the University of Tulsa School of Law, who is co-author of an exhaustive history of desegregation in the Fifth Cir- cuit, was kind enough to confirm my own estimation of the judges from his broad and informed perspective. -

United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals Fifth Federal Judicial Circuit Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas Circuit Judges Priscilla R. Owen, Chief Judge ...............903 San Jacinto Blvd., Rm. 434 ..................................................... (512) 916-5167 Austin, Texas 78701-2450 Carl E. Stewart ......................................300 Fannin St., Ste. 5226 ............................................................... (318) 676-3765 Shreveport, LA 71101-3425 Edith H. Jones .......................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12505 ................................... (713) 250-5484 Houston, Texas 77002-2655 Jerry E. Smith ........................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12621 ................................... (713) 250-5101 Houston, Texas 77002-2698 James L. Dennis ....................................600 Camp St., Rm. 219 .................................................................. (504) 310-8000 New Orleans, LA 70130-3425 Jennifer Walker Elrod ........................... 515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12014 .................................. (713) 250-7590 Houston, Texas 77002-2603 Leslie H. Southwick ...............................501 E. Court St., Ste. 3.750 ........................................................... (601) 608-4760 Jackson, MS 39201 Catharina Haynes .................................1100 Commerce St., Rm. 1452 ..................................................... (214) 753-2750 Dallas, Texas 75242 James E. Graves Jr. ................................501 E. Court -

Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Louisiana Law Review Volume 80 Number 4 Summer 2020 Article 9 11-11-2020 Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Ronald J. Scalise Jr., Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, 80 La. L. Rev. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol80/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 1332 I. A (Very Brief) History of Wills in the United States ................. 1333 A. Functions of Form Requirements ........................................ 1335 B. The Law of Yesterday: The Development of Louisiana’s Will Forms ....................................................... 1337 II. Compliance with Formalities ..................................................... 1343 A. The Slow Migration from “Strict Compliance” to “Substantial Compliance” to “Harmless Error” in the United States .............................................................. 1344 B. Compliance in Other Jurisdictions, Civil and Common .............................................................. -

Joseph Crespino Jimmy Carter Professor Department of History Emory University

Joseph Crespino Jimmy Carter Professor Department of History Emory University 561 Kilgo St. [email protected] 221 Bowden Hall, 404-727-6555 w Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-4959 f Employment Jimmy Carter Professor of American History, Emory 2014-present University, Atlanta, Georgia Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2012-2014 Associate Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2008-2012 Assistant Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2003-2008 Social Studies Teacher, Gentry High School, Indianola 1994-1996 School District, Indianola, Mississippi Education Stanford University, Stanford, California M.A., Ph.D., Department of History 1996-2002 University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi M.Ed. Secondary School Education 1994-1996 Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois B.A. American Culture 1990-1994 Fellowships, Grants, & Awards Distinguished Lecturer, Organization of American Historians 2012-present Senior Fellow, Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, 2016-2017 Emory University Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, 2014 Joseph Crespino 2 University of Tübingen, Germany Awards for Strom Thurmond’s America: 2013-2104 Deep South Book Prize, Summersell Center, University of Alabama; Georgia Author of the Year, Biography Prize; Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters, Nonfiction Book Prize National Endowment for the Humanities Summer 2009 Stipend Award Emory University Center for Teaching and Curriculum, Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching Award 2009 Awards for In Search of Another Country: 2008 Lillian Smith Book Award; McLemore Prize, Mississippi Historical Society; Nonfiction Award, Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Ellis Hawley Prize, Journal of Policy History, for 2008 “The Best Defense is a Good Offense: The Stennis Amendment and the Fracturing of Liberal School Desegregation Policy” National Academy of Education/ Spencer Foundation 2006-2007 Postdoctoral Fellowship J.N.G. -

An Evaluation of Autobiographical Elements in Harper Lee's Novel To

Telling Narratives: an evaluation of autobiographical elements in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mocking Bird A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Arts and Languages For the Award of the Degree of Master of English By Akanshya Handique Regd. No: 11511530 Supervisor Dr. Shreya Chatterji Associate Professor Faculty of Arts and Languages Lovely Professional University Phagwara, Punjab, India 2017 Abstract Harper Lee‘s To Kill a Mockingbird is read as an autobiographical fiction in which autobiographical manifestation of the writer‘s life are decorated through the incorporation of imaginary tale and truth. Functionality of facts in Lee‘s work seems to endowment fiction, unlike purposes that serve factuality more than fallaciousness. The confines of our study are going cover up the investigation about the prejudices in terms of race, class and gender inequalities in To Kill a Mocking bird. Particularly the essentials of autobiography present in the novel. It also centers on how the elements are related to one another. The purpose of the work is to explore the autobiographical elements present in the work of fiction To Kill a Mockingbird which also demonstrates the discrimination of race, class and gender that was prevalent in South America during 1930s and further evaluate the narrative technique used. This thesis proposes to understand the novel To Kill a Mockingbird from the approach based on the New Historicism Theory. New Historicism theory analyses a novel with reference to the historical situation. It states that work cannot be evaluated without the consideration of the era in which it was created. Keywords: autobiographical features, prejudice, historical context, narrative technique and race and gender inequality. -

Invalid Forensic Science Testimony and Wrongful Convictions

VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 95 MARCH 2009 NUMBER 1 ARTICLES INVALID FORENSIC SCIENCE TESTIMONY AND WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS Brandon L. Garrett*and Peter J. Neufeld** THIS is the first study to explore the forensic science testimony by prosecution experts in the trials of innocent persons, all convicted of serious crimes, who were later exonerated by post-conviction DNA testing. Trial transcripts were sought for all 156 exonerees identified as having trial testimony by forensic analysts, of which 137 were located and reviewed. These trials most commonly included testimony concern- ing serological analysis and microscopic hair comparison, but some in- * Associate Professor, University of Virginia School of Law. **Co-Founder and Co-Director, The Innocence Project. For their invaluable comments, we thank Kerry Abrams, Edward Blake, John Butler, Paul Chevigny, Simon Cole, Madeline deLone, Jeff Fagan, Stephen Fienberg, Samuel Gross, Eric Lander, David Kaye, Richard Lewontin, Greg Mitchell, John Monahan, Erin Murphy, Sinead O'Doherty, George Rutherglen, Stephen Schulhofer, William Thompson, Larry Walker, and participants at the Harvard Criminal Justice Roundta- ble, a UVA School of Law summer workshop, and the Ninth Annual Buck Colbert Franklin Memorial Civil Rights Lecture at the University of Tulsa College of Law. The authors thank the participants at the Fourth Meeting of the National Academy of Science, Committee on Identifying the Needs of the Forensic Sciences Community for their useful comments, and we thank the Committee for inviting our participation at that meeting. Preliminary study data were presented as a report to the Committee on February 1, 2008. We give special thanks to all of the attorneys who graciously volun- teered their time to help locate and copy exonerees' criminal trial transcripts, and par- ticularly Winston & Strawn, LLP for its work in locating and scanning files from DNA exonerees' cases. -

The Fifth Circuit Four: the Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Divisio

The Fifth Circuit Four: The Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Division Historical Paper Length: 2,500 Words 1 “For thus saith the Lord God, how much more when I send my four sore judgments upon Jerusalem, the sword, and the famine, and the noisome beast, and the pestilence, to cut off from it man and beast.”1 In the Bible, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are said to usher in the end of the world. That is why, in 1964, Judge Ben Cameron gave four of his fellow judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit the derisive nickname “the Fifth Circuit Four” – because they were ending the segregationist world of the Deep South.2 The conventional view of the civil rights struggle is that the Southern white power structure consistently opposed integration.3 While largely true, one of the most powerful institutions in the South, the Fifth Circuit, helped to break civil rights barriers by enforcing the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, something that other Southern courts were reluctant to do.4 Despite personal and professional backlash, Judges John Minor Wisdom, Elbert Tuttle, Richard Rives, and John Brown played a significant but often overlooked role in integrating the South.5 Background on the Fifth Circuit The federal court system, in which judges are appointed for life, consists of three levels.6 At the bottom are the district courts, where cases are originally heard by a single trial judge. At 1 Ezekiel 14:21 (King James Version). -

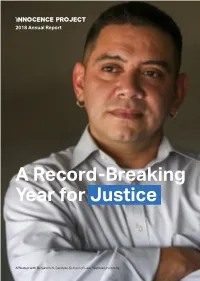

A Record-Breaking Year for Justice

2018 Annual Report A Record-Breaking Year for Justice Affiliated with Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University The Innocence Project was founded in 1992 by Barry C. Scheck and Peter J. Neufeld at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University to assist incarcerated people who could be proven innocent through DNA testing. To date, more than 360 people in the United States have been exonerated by DNA testing, including 21 who spent time on death row. These people spent an average of 14 years in prison before exoneration and release. The Innocence Project’s staff attorneys and Cardozo clinic students provided direct representation or critical assistance in most of these cases. The Innocence Project’s groundbreaking use of DNA technology to free innocent people has provided irrefutable proof that wrongful convictions are not isolated or rare events, but instead arise from systemic defects. Now an independent nonprofit organization closely affiliated with Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, the Innocence Project’s mission is to free the staggering number of innocent people who remain incarcerated and to bring substantive reform to the system responsible for their unjust imprisonment. Letter from the Co-Founders, Board Chair and Executive Director ........................................... 3 FY18 Victories ................................................................................................................................................ 4 John Nolley .................................................................................................................................................... -

Lawyers in Love ... with Lawyers

BBarar Luncheon:Luncheon: TTuesday,uesday, FFeb.eb. 1199 IInside:nside: FFrackingracking Alt.Alt. WWellsells AAttorneyttorney sspotlight:potlight: LLarandaaranda MMoffoff eetttt WWalkeralker IInterviewnterview wwithith FFamilyamily CCourtourt LLawyersawyers inin LoveLove ...... JJudgeudge CharleneCharlene CCharletharlet DDayay wwithith LLawyersawyers Dear Chief Judge and Judges of the 19th JDC, It has come to my attention that our Court is about to approve a policy concerning the use of cellphones in our courthouse. I am told that what is being considered is that only attorneys with bar cards and court personnel will be allowed to bring a cellphone into our courthouse. On behalf of the Baton Rouge Bar Association, I request that we be allowed some input into this decision. I understand that the incident that prompted this policy decision is a person using a cellphone to video record a proceeding in a courtroom. That conduct, of course, is unacceptable. I would like to address with the Court options other than banning cellphones. I would suggest we use signs telling those in the courtroom that, if they wish to use their cellphone, they need to walk out into the hallway and that, if anyone is caught using a cellphone in the courtroom, the cellphone will be taken away and they will be held in contempt of court. The bailiff can announce this before the judge takes the bench. 2013 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Here is our concern: As you know, there are no payphones in the courthouse. Scenario 1: One of our citizens comes to our courthouse as a witness in a trial or to come to the clerk’s offi ce for some reason.