In the Volta River Basin Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Africa

G8202 AFRICA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G8202 .C5 Chad, Lake .N5 Nile River .N9 Nyasa, Lake .R8 Ruzizi River .S2 Sahara .S9 Sudan [Region] .T3 Tanganyika, Lake .T5 Tibesti Mountains .Z3 Zambezi River 2717 G8222 NORTH AFRICA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G8222 ETC. .A8 Atlas Mountains 2718 G8232 MOROCCO. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G8232 .A5 Anti-Atlas Mountains .B3 Beni Amir .B4 Beni Mhammed .C5 Chaouia region .C6 Coasts .D7 Dra region .F48 Fezouata .G4 Gharb Plain .H5 High Atlas Mountains .I3 Ifni .K4 Kert Wadi .K82 Ktaoua .M5 Middle Atlas Mountains .M6 Mogador Bay .R5 Rif Mountains .S2 Sais Plain .S38 Sebou River .S4 Sehoul Forest .S59 Sidi Yahia az Za region .T2 Tafilalt .T27 Tangier, Bay of .T3 Tangier Peninsula .T47 Ternata .T6 Toubkal Mountain 2719 G8233 MOROCCO. PROVINCES G8233 .A2 Agadir .A3 Al-Homina .A4 Al-Jadida .B3 Beni-Mellal .F4 Fès .K6 Khouribga .K8 Ksar-es-Souk .M2 Marrakech .M4 Meknès .N2 Nador .O8 Ouarzazate .O9 Oujda .R2 Rabat .S2 Safi .S5 Settat .T2 Tangier Including the International Zone .T25 Tarfaya .T4 Taza .T5 Tetuan 2720 G8234 MOROCCO. CITIES AND TOWNS, ETC. G8234 .A2 Agadir .A3 Alcazarquivir .A5 Amizmiz .A7 Arzila .A75 Asilah .A8 Azemmour .A9 Azrou .B2 Ben Ahmet .B35 Ben Slimane .B37 Beni Mellal .B4 Berkane .B52 Berrechid .B6 Boujad .C3 Casablanca .C4 Ceuta .C5 Checkaouene [Tétouan] .D4 Demnate .E7 Erfond .E8 Essaouira .F3 Fedhala .F4 Fès .F5 Figurg .G8 Guercif .H3 Hajeb [Meknès] .H6 Hoceima .I3 Ifrane [Meknès] .J3 Jadida .K3 Kasba-Tadla .K37 Kelaa des Srarhna .K4 Kenitra .K43 Khenitra .K5 Khmissat .K6 Khouribga .L3 Larache .M2 Marrakech .M3 Mazagan .M38 Medina .M4 Meknès .M5 Melilla .M55 Midar .M7 Mogador .M75 Mohammedia .N3 Nador [Nador] .O7 Oued Zem .O9 Oujda .P4 Petitjean .P6 Port-Lyantey 2721 G8234 MOROCCO. -

Modelling West African Total Precipitation Depth: a Statistical Approach

AgiAl The Open Access Journal of Science and Technology Publishing House Vol. 3 (2015), Article ID 101120, 7 pages doi:10.11131/2015/101120 http://www.agialpress.com/ Research Article Modelling West African Total Precipitation Depth: A Statistical Approach S. Sovoe Environmental Protection Agency, Ho, Volta Region, Ghana Corresponding Author: S. Sovoe; email: [email protected] Received 27 August 2014; Accepted 29 December 2014 Academic Editor: Isidro A. Pérez Copyright © 2015 S. Sovoe. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract. Even though several reports over the past few decades indicate an increasing aridity over West Africa, attempts to establish the controlling factor(s) have not been successful. The traditional belief of the position of the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) as the predominant factor over the region has been refuted by recent findings. Changes in major atmospheric circulations such as African Easterly Jet (AEJ) and Tropical Easterly Jet (TEJ) are being cited as major precipitation driving forces over the region. Thus, any attempt to predict long term precipitation events over the region using Global Circulation or Local Circulation Models could be flawed as the controlling factors are not fully elucidated yet. Successful prediction effort may require models which depend on past events as their inputs as in the case of time series models such as Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model. In this study, historical precipitation data was imported as time series data structure into an R programming language and was used to build appropriate Seasonal Multiplicative Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average model, ARIMA (푝, 푑, 푞)∗(푃 , 퐷, 푄). -

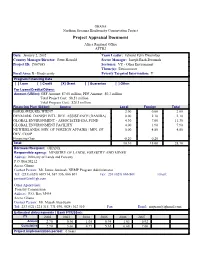

Project Appraisal Document

GHANA Northern Savanna Biodiversity Conservation Project Project Appraisal Document Africa Regional Office AFTR2 Date: January 2, 2002 Team Leader: Edward Felix Dwumfour Country Manager/Director: Peter Harrold Sector Manager: Joseph Baah-Dwomoh Project ID: P067685 Sector(s): VY - Other Environment Theme(s): Environment Focal Area: B - Biodiversity Poverty Targeted Intervention: Y Program Financing Data [ ] Loan [ ] Credit [X] Grant [ ] Guarantee [ ] Other: For Loans/Credits/Others: Amount (US$m): GEF Amount: $7.60 million; PDF Amount: $0.3 million Total Project Cost: $8.51 million Total Program Cost: $28.1 million Financing Plan (US$m): Source Local Foreign Total BORROWER/RECIPIENT 2.00 0.00 2.00 DENMARK: DANISH INTL. DEV. ASSISTANCE (DANIDA) 0.00 2.10 2.10 GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT - ASSOCIATED IDA FUND 4.30 7.00 11.30 GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY 4.00 3.90 7.90 NETHERLANDS: MIN. OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS / MIN. OF 0.00 4.80 4.80 DEV. COOP. Financing Gap -0.20 0.20 Total: 10.10 18.00 28.10 Borrower/Recipient: GHANA Responsible agency: MINISTRY OF LANDS, FORESTRY AND MINES Address: Ministry of Lands and Forestry P.O. Box M212 Accra, Ghana Contact Person: Mr. James Amissah, NRMP Program Administrator Tel: (233) (021) 687314, 687 336, 666 801 Fax: 233 (021) 666 801 Email: [email protected] Other Agency(ies): Forestry Commission Address: P.O. Box M434 Accra, Ghana Contact Person: Mr. Musah Abu-Juam Tel: 233 (021) 221 315, 771 690, (024) 362 510 Fax: Email: [email protected] Estimated disbursements ( Bank FY/US$m): FY 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Annual 2.70 0.96 1.05 0.94 1.03 0.92 Cumulative 2.70 3.66 4.71 5.65 6.68 7.60 Project implementation period: 6 years OCS PAD Form: Rev. -

The Ghana Butterfly Fauna and Its Contribution to the Objectives of the Protected Areas System

WILDLIFE DIVISION (FORESTRY COMMISSION) REPUBLIC OF GHANA Wildlife Division Support Project (WDSP) The Ghana Butterfly Fauna and its Contribution to the Objectives of the Protected Areas System by Torben B Larsen (WDSP Report No. 63) March 2006 In collaboration with: TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………………..….. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………… 12 1. INTRODUCTION ………………………………………… 13 1.1 Background to the present mission …………………………. 13 1.2 Objectives of the present mission …………………………… 14 2. BUTTERFLIES AS INDICATOR SPECIES ……………. 16 2.1 Butterflies as indicators for overall biodiversity …………… 16 2.2 Butterflies as indicators of comparative diversity ………….. 17 2.3 Butterflies as ecological indicator species …………………. 18 2.4 Butterflies as biogeographical indicator species …………… 19 2.5 Butterflies as conservation indicators ……………………… 19 2.6 Butterflies as indicators of extinction ……………………… 20 2.7 Discussion …………………………………………………. 22 3. BUTTERFLIES OF THE PROTECTED AREAS ………. 23 3.1 Material and methods ……………………………………… 23 3.2 Ghana butterflies and the main ecological zones ………….. 24 3.3 Coverage of butterflies by the protected areas system …….. 26 3.3.1 Overall butterfly coverage by the protected areas system …… 26 3.3.2 Coverage of the endemic species west of Dahomey Gap .…… 28 3.3.3 Specific comments on the Ghana subregion endemics ….…… 31 3.3.4 Coverage of butterflies by the protected areas system in different ecological zones ……………………….………… 33 3.3.4.a Forest zone (excluding Volta Region) ……………… 33 3.3.4.b Volta Region …………………….………………….. 36 3.3.4.c Savannah zone ……………………….……………… 38 i) Forest-savannah transition ……………………… 39 ii) Guinea Savannah …………..…………………… 41 iii) Sudan Savannah ………………………………... 43 3.3.4.d Ubiquitous species …………………………………… 47 3.4 Recapitulation of coverage by the protected areas system …. -

A Koma Site in Northern Ghana

Investigating Ancient Human Occupation at Zoboku: A Koma Site in Northern Ghana Joyce Ampofoa Dartey Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas University of East Anglia March 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. i Dedication I dedicate this thesis to Nana Akwasi, Papa Kwabena, Maame Yaa Affoah and Adom Ofori, for the many challenges and rewards. ii Abstract It was the highly elaborate terracotta figurines that drew research attention to the Koma archaeological sites in northern Ghana in the mid-1980s. Since then, several mounds in the area have suffered the ravages of illicit looting and sale of the figurines, resulting in a loss of essential contextual and archaeological information. Nevertheless, scientific research has also made considerable advances in examining and revealing some aspects of the social, ritual and technological organisation of the past Koma societies. For example, research has revealed that the Koma sites were probably inhabited as early as the sixth century AD. It has also been revealed that some of the mounds are the remains of ritual actions possibly focused on healing and ancestor veneration practices, in which figurines and other objects were specially curated, used and ultimately deposited in special spatial arrangements. -

Water Audit of the Volta Basin

Water Audit Volta Basin - Final Report WORLD CONSERVATION UNION (IUCN) (WEST AFRICAN REGIONAL OFFICE) PROJECT FOR IMPROVING WATER GOVERNANCE IN THE VOLTA BASIN (PAGEV) WATER AUDIT OF THE VOLTA BASIN FINAL REPORT Nii Consult P.O. Box OS 981 Osu – Accra. Tel: 233-21-761007 Fax: 233-21-761008 E-mail: [email protected] Nii Consult – August 2007 Water Audit Volta Basin - Final Report AUGUST, 2007 Nii Consult – August 2007 Water Audit Volta Basin - Final Report LIST OF ACRONYMS AND APPREVIATIONS BF - Burkina Faso BMB - German Ministry of Education and Research CD - Compact Disk CSIR - Council for Scientific and Industrial Research DGRIH - Direction General for Inventory of Hydraulic Resources (Burkina Faso) DSS Decision Support System GLOWA - Global Hydrological Cycle GMA - Ghana Meteorological Agency GOG - Government of Ghana HSD - Hydrological Services Department HYCOS - Hydrological Cycle Observing System IUCN - World Conservation Union IWRM - Integrated Water Resources Management NMI - National Meteorological Institute ONEA - National Office for Water and Sewerage PAGEV - Project for Improving Water Governance in the Volta Basin PET - Potential Evapotranspiration SAP - Strategic Action Plan SONABEL - National Electricity Company of Burkina Faso TDA - Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis VBTC - Volta Basin Technical Committee WEAP - Water Evaluation and Planning System Nii Consult – August 2007 i Water Audit Volta Basin - Final Report Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................. -

JPC CCP Bureau Du President

Onchocerciasis Control Programme in West Africa Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose en Afrique de I'Ouest JOINT PROGRAMME COMMITTEE - COMITE CONJOINT DU PROGRAMME Office of the Chairman JPC CCP Bureau du President tPct3.2 I JOINT PROGRAMME COMMITTEE (@P/PR/ez) I I Thirteenth session ORIGINAL: FRENCH Geneva. 8-l I December 1992 September 1992 ; Provisional aqenda item 6 PROGRESS REPORT OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION FOR 1992 (l September l99l - 3l August 1992) Table of contents Pagp SUMMARY YECTOR CONTROL 6 Climatic conditions 6 Aircraft fleet and aerial operations 6 Treated areas . 6 Insecticides and control strategy 7 Hydrology and teletransmission 7 Surveillance and entomological evaluation network l0 Entomological activities of national teams in the south-western extension zone l0 Results obtained l0 Larviciding efficacy l0 Reinvasion and resistance l0 Transmission . ll Post-control entomological studies ll Monitoring of the aquatic environment . ll JPCl3.2 IVERMECTTN(ocP/PR/e2) (MECTIZANR) DISTRIBUTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES t2 IvermectinPage 2 distribution t2 Epidemiological evaluation l3 Special ophthalmological studies t4 MigrationTRAINING studies t4.....20 Special case of women 2t BIOSTATISTTCSCase AND of countriesINFORMATION outside theSTYSTEMS OCP area 15 22 TNTERDISCPLINARYRESEARCH..DEYOLUTION.. ....16 .....22 InsecticidesRestructuringof theunit. ..... 16.....22 I VectorandparasiteidentificationPublicawarnessandpopulationmobilizationeffort ....12 ...... 22 ModellingEpidemiological surveillance and ivermectin -

Project-Information-Document-Ghana

The World Bank Ghana Landscape Restoration and Small Scale Mining Project (P171933) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Project Information Document (PID) Appraisal Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 24-Apr-2021 | Report No: PIDA28521 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized April 22, 2021 Page 1 of 36 The World Bank Ghana Landscape Restoration and Small Scale Mining Project (P171933) BASIC INFORMATION OPS_TABLE_BASIC_DATA A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Project Name Parent Project ID (if any) Ghana P171933 Ghana Landscape Restoration and Small Scale Mining Project Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA WEST 26-Apr-2021 31-Aug-2021 Environment, Natural Resources & the Blue Economy Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing The Republic of Ghana Environmental Protection Agency, Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Proposed Development Objective(s) to strengthen integrated natural resource management and increase benefits to communities in targeted savannah and cocoa forest landscapes Components Component 1: Institutional Strengthening for Participatory Landscape Management Component 2: Enhanced governance in support of sustainable ASM Component 3: Sustainable Crop and Forest Landscape Management Component 4: Project Monitoring and Knowledge Management Component 5. Contingent Emergency Response PROJECT FINANCING DATA (US$, Millions) SUMMARY-NewFin1 Total Project Cost 102.76 Total Financing 102.76 of which IBRD/IDA 75.00 Financing Gap 0.00 DETAILS-NewFinEnh1 April 21, 2021 Page 2 of 36 The World Bank Ghana Landscape Restoration and Small Scale Mining Project (P171933) World Bank Group Financing International Development Association (IDA) 75.00 IDA Credit 75.00 Non-World Bank Group Financing Trust Funds 27.76 Global Environment Facility (GEF) 12.76 Global P'ship for Sust. -

White Volta IWRM Plan

WATER RESOURCES COMMISSION, GHANA WHITE VOLTA RIVER BASIN - Integrated Water Resources Management Plan December 2008 Water Resources Commission White Volta River Basin IWRM Plan PREAMBLE Right from the establishment of the Water Resources Commission (WRC) a priority task has been to introduce the basic principles of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) at decentralised level in selected river basins. The first IWRM Plan elaborated was for the Densu River Basin which was finalised towards the middle of 2007. The present White Volta River Basin IWRM Plan is the second of its kind, and this basin was chosen due to the trends witnessed here, including detrimental land and water quality degradation, water shortages in an otherwise perennial river system caused, among other factors, by an accelerating increase in irrigation demand, and establishment of numerous smaller dams and dug-outs in the upstream parts of the river system. Additionally, as experienced in the rainy season of 2007, occasional devastating flood events also occur. These hazards may very well also be indirect caused by new patterns in river runoff as result of an ongoing climate change. In instituting proper water resource management mechanisms, the White Volta River Basin is also unique in the Ghanaian context being a true frontier river system, which calls for special “trans-boundary” considerations in the approach towards water resources planning and development of this internationally shared resource. A number of activities have been invested over the past few years in creating a basin-based IWRM structure for the White Volta River Basin. The decentralised IWRM structure, which has evolved through a targeted participatory and consultative process, combines the following partners: a broadly anchored stakeholder-oriented coordinating body, i.e. -

Ecosystem Valuation Background Paper for Northern Ghana October 2017

Ecosystem Valuation Background Paper for Northern Ghana October 2017 Feed the Future Ghana Agriculture and Natural Resource Management Project Ecosystem Valuation Background Paper for Northern Ghana Agreement Number: AID-641-A-16-00010 Authors: Alexandre M. Grais, Gabriel Sidman, Michael Netzer, Therese Tepe, and Timothy Pearson; Winrock International DISCLAIMER The report was made possible through the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Feed the Future initiative. The contents are the responsibility of Winrock International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. ii Table of Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................... 1 Ecosystem Services and PES Schemes ..................................................................................................... 1 Ecosystem Services in northern Ghana .................................................................................................. 1 Potential PES schemes in northern Ghana ............................................................................................. 2 Design and Next Steps for Ecosystem Services and Payment for Ecosystem Services ............... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 Background ................................................................................................................................................... -

World Bank Document

Document of Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD978 PROJECT PAPER ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED ADDITIONAL GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF $ 8.75 MILLION FROM THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND TO THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized SUSTAINABLE LAND AND WATER MANAGEMENT PROJECT MAY 28, 2014 Environment, Natural Resources, Water and Disaster Risk Management (AFTN3) Western Africa 1 (AFCW1) Africa Region This document is being made publicly available prior to Board consideration. This does Public Disclosure Authorized not imply a presumed outcome. This document may be updated following Board consideration and the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s policy on Access to Information. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective April 17, 2014) Currency Unit = Ghana Cedi Ghana Cedi 2.77 = US$1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CEA Country Environmental Analysis CPS Country Partnership Strategy CREMA Community Resource Management Area DADU District Agriculture Development Unit EAMP Environmental Analysis and Management Plan EPA Environment Protection Agency FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FC Forestry Commission FCPF Forest Carbon Partnership Facility FIP Forest Investment Program FM Financial Management FMP Forest Management Plan FSD Forest Services Division [of the Forestry Commission] GCAP Ghana Commercial Agriculture Project GDP Gross Domestic Product GEF Global Environment Facility GEO -

Modelling Riverflow in the Volta Basin of West Africa: a Data-Driven Framework

MODELLING RIVERFLOW IN THE VOLTA BASIN OF WEST AFRICA: A DATA-DRIVEN FRAMEWORK Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, prof. dr. ir. J.T. Fokkema, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 18 januari 2006 om 10.30 uur door Barnabas Akurigo AMISIGO Master of Science, University of Guelph geboren te Bolgatanga, Ghana Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof.dr.ir. N.C. van de Giesen Technische Universiteit Delft, The Netherlands Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus Technische Universiteit Delft, voorzitter Prof. dr. ir. N.C. van de Giesen Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Prof. dr. J.J. Bogardi United Nations University Prof. dr. ir. A.W. Heemink Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr. A.E. Mynett Technische Universiteit Delft / UNESCO IHE Prof. dr. ir. H.H.G. Savenije Technische Universiteit Delft / UNESCO IHE Prof. dr. ir. G.S. Stelling Technische Universiteit Delft Dissertation prepared at the Center for Development Research, University of Bonn, in the context of the GLOWA Volta Project "Sustainable water use under changing land use, rainfall reliability and water demands in the Volta Basin" financed by the Ministry of Science and Education (BMBF) of the Federal Republic of Germany. To my parents for their foresight, and to my wife Hawa and daughter Mmalebna ABSTRACT The 400,000 km2 Volta Basin is an international basin covering almost 28% of the West Coast. Basin of Africa. It extends from longitude 5o 30 W to 2o 00E and from latitude 5 30o N to 14o 30 N and is shared by the six West African countries Benin, Togo, Ghana, La Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Mali.