And Property in Ip): a Comment on Justifying Intellectual Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leases and the Rule Against Perpetuities

LEASES AND THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES EDWIN H. ABBOT, JUNIOR of the Boston Bar INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule against perpetuities to leases. A leasehold estate has certain peculiari- ties which distinguish it, as a practical matter, from other estates in land. At common law it required no livery of seisin, and so could be created to begin in futuro. Although it is not an estate of freehold the duration of the estate may be practically unlimited-it may be for 999 years or even in perpetuity. The reversion after an estate for years is necessarily vested, no matter how long the term of the lease may be, yet the leasehold estate is generally terminable at an earlier time upon numerous conditions subsequent, defined in the lease. In other words the leasehold estate determines without condition by the effluxion of the term defined in the lease but such termination may be hastened by the happening of one or more conditions. The application of the rule against perpetuities to such an estate presents special problems. The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule to the creation, termination and renewal of leases; and also its effect upon options inserted in leases. II CREATION A leasehold estate may be created to begin in futuro, since livery of seisin was not at common law required for its creation. Unless limited by the rule a contingent lease might be granted to begin a thousand years hence. But the creation of a contingent estate for years to begin a thousand years hence is for practical reasons just as objectionable as the limitation of a contingent fee to begin at such a remote period by means of springing or shifting uses, or by the device of an execu- tory devise. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

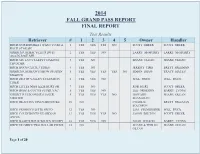

Fall Grand Pass Report Final Report

2014 FALL GRAND PASS REPORT FINAL REPORT Test Results Retriever # 1 2 3 4 5 Owner Handler HRCH NORTHFORKS I WANT TO BE A 1 YES YES YES NO SCOTT GREER SCOTT GREER ROCK STAR SH GRHRCH UH MAC'S LET'S DO IT 2 YES YES NO LARRY McMURRY LARRY McMURRY AGAIN JOSIE MH HRCH UH LUCY'S LEFTY DAKOTA 3 YES NO SHANE OLEAN SHANE OLEAN THUNDER HRCH BOO'S CLICK 3 TIMES 4 YES NO JEREMY TIMS BRETT FREEMAN GRHRCH UH SHAW'S SHOW STOPPIN' 5 YES YES YES YES NO SIMON SHAW TRACY HAYES SHADOW HRCH DEATH VALLEY'S CLEMSON 6 YES YES NO WILL PRICE WILL PRICE TIGER HRCH LITTLE MISS IZZIE HURT SH 7 YES NO ROB HURT SCOTT GREER HRCH BOSS & COCO'S SUPER VAC 8 YES YES NO LEE ORGERON BARRY LYONS GRHRCH UH BOOMER'S JAGER 9 YES YES YES NO HOWARD SHANE OLEAN MEISTER SHANAHAN HRCH DEACON'S VINEYARD DUKE 10 NO CHARLIE BRETT FREEMAN SOLOMON HRCH FROGGY'S LITTE FRITO 12 YES NO LISA STEMBRIDGE WILL PRICE HRCH COLDFRONTS GUARDIAN 13 YES YES YES NO JASON BELTON SCOTT GREER ANGEL HRCH BASIC'S ROUX WILD'N WOODY 14 YES YES NO NOAH WILSON BARRY LYONS HRCH UH SDK'S TWO DOLLAR PISTOL 15 NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN Page 1 of 20 HRCH ACADEMY'S HIGHWAY JUNKIE 16 YES YES YES NO DEREK & MELINDA BRETT FREEMAN RANDLE HRCH MEGAN'S BLACK ROSE 17 NO MARSHA HINCHER TRACY HAYES HRCH BULLET'S BIG TRIGGER 18 YES YES YES YES YES BRIAN SULLIVAN WILL PRICE HRCH SPOOKS TIMBER TIN LIZZY 19 YES YES YES NO WADE OLIVER SCOTT GREER HRCH BLUE'S & ROUX'S RAJIN 20 YES YES NO GLENN POST BARRY LYONS PUNKIN HRCH SDK'S MORE COWBELL 21 YES YES YES NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN HRCH ACADEMY'S DO WHAT I DO -

Aes 143Rd Convention Program October 18–21, 2017

AES 143RD CONVENTION PROGRAM OCTOBER 18–21, 2017 JAVITS CONVENTION CENTER, NY, USA The Winner of the 143rd AES Convention To be presented on Friday, Oct. 20, Best Peer-Reviewed Paper Award is: in Session 15—Posters: Applications in Audio A Statistical Model that Predicts Listeners’ * * * * * Preference Ratings of In-Ear Headphones: Session P1 Wednesday, Oct. 18 Part 1—Listening Test Results and Acoustic 9:00 am – 11:00 am Room 1E11 Measurements—Sean Olive, Todd Welti, Omid Khonsaripour, Harman International, Northridge, SIGNAL PROCESSING CA, USA Convention Paper 9840 Chair: Bozena Kostek, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland To be presented on Thursday, Oct. 18, in Session 7—Perception—Part 2 9:00 am P1-1 Generation and Evaluation of Isolated Audio Coding * * * * * Artifacts—Sascha Dick, Nadja Schinkel-Bielefeld, The AES has launched an opportunity to recognize student Sascha Disch, Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated members who author technical papers. The Student Paper Award Circuits IIS, Erlangen, Germany Competition is based on the preprint manuscripts accepted for the Many existing perceptual audio codec standards AES convention. define only the bit stream syntax and associated decod- A number of student-authored papers were nominated. The er algorithms, but leave many degrees of freedom to the excellent quality of the submissions has made the selection process encoder design. For a systematic optimization of encod- both challenging and exhilarating. er parameters as well as for education and training of The award-winning student paper will be honored during the experienced test listeners, it is instrumental to provoke Convention, and the student-authored manuscript will be consid- and subsequently assess individual coding artifact types ered for publication in a timely manner for the Journal of the Audio in an isolated fashion with controllable strength. -

False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note Goerge W

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Natural Law Forum 1-1-1956 False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note Goerge W. Constable Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constable, Goerge W., "False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note" (1956). Natural Law Forum. Paper 9. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Law Forum by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FALSE NATURAL LAW: PROFESSOR GOBLE'S STRAW MAN To ALL WHO FOLLOW the trends here and abroad in legal philosophy, it has become apparent that the tide which has run so strongly against natural law theory for many decades, has now begun to turn. As the fatal emptiness in the heart of positivism becomes more exposed with each fresh assault upon freedom by evil ideologies and with every new example of antisocial individualism, the natural law position wins more attention and regains more of its ancient prestige.' For the natural law position, in the classical and Scholastic sense, is gradually revealing itself for what it is-as a strong central defense point between two extremes, seeking at once to secure for us proper individual freedoms and to impose upon us proper social duties.2 Significant in this turn of the tide is the article of George W. Goble entitled "Nature, Man and Law: The True Natural Law" (A.B.A.J., May 1955). -

More Cowbell: a Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations Lt Col Will Atkins, USAF Lt Col Donghyung Cho, ROK MAJ Sean Yarroll, USA

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL - FEATURE More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations LT COL WILL ATKINS, USAF LT COL DONGHYUNG CHO, ROK MAJ SEAN YARROLL, USA Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. To put it simply, we need to worry a lot less about how to communicate our actions and much more about what our actions communicate. —Former Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm Michael G. Mullen, August 2009 Introduction In a popular “Saturday Night Live” skit from 2000, despite the cowbell depicted as an afterthought in a fully integrated band, the audience learns a valuable lesson on the importance of “more cowbell.”1 To continue the metaphor, the cowbell has never been and will never be the primary line of effort in the band. But the cow- bell permeates throughout the music, often tying the entire performance together. Such is the fate of information operations in a joint environment, often consid- 20 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL SUMMER 2020 More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations ered a “second- class citizen as a source of nonlethal effects, an afterthought bolt- on to fires, or worse.”2 On the contrary, information operations is often the capa- bility that binds joint operations together to make it successful. -

Water Rights and Responsibilities in the Twenty-First Century: a Foreword to the Proceedings of the 2001 Symposium on Managing Hawai‘I’S Public Trust Doctrine

WATER RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: A FOREWORD TO THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2001 SYMPOSIUM ON MANAGING HAWAI‘I’S PUBLIC TRUST DOCTRINE By Denise E. Antolini1 I. INTRODUCTION Modern water allocation decisions inevitably involve difficult choices among competing consumptive and natural uses that are highly valued by diverse but equally passionate sectors of the community.2 Particularly in an island state like Hawai‘i, with its limited sources of fresh water, fragile environment, and unique economic challenges, debates over re-allocation of precious water resources and the merits of stream restoration are likely to become only more intense as human needs for 1 Assistant Professor of Law at the William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai`i at Manoa; former Managing Attorney, Mid- Pacific Office, Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (SCLDF), Honolulu, Hawai`i; J.D., 1986, University of California at Berkeley, Boalt Hall; A.B., 1982, Princeton University. Prior to joining the law school faculty, Ms. Antolini represented the “windward parties” (Wai_hole- Waik_ne Community Association, Hakipu`u `Ohana, Kahalu`u Neighborhood Board, and Ka L_hui Hawai`i) in the first phase of the Wai_hole contested case hearing. Special thanks to: Bill Tam, Michelle Kaneshiro-Oishi, and Christine Griffin of Carnazzo Court Reporting for their generous assistance. Contact the author at: antolini@hawai`i.edu. 2 See Robbie Dingeman, Wai_hole Water Allocation Rejected: Ruling Called Windward Victory, HONOLULU ADVERTISER, Aug. 23, 2000, -

Secret Destruction of Joint Tenant Survivorship Rights

Fordham Law Review Volume 55 Issue 2 Article 2 1986 An Invitation to Commit Fraud: Secret Destruction of Joint Tenant Survivorship Rights Samuel M. Fetters Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel M. Fetters, An Invitation to Commit Fraud: Secret Destruction of Joint Tenant Survivorship Rights, 55 Fordham L. Rev. 173 (1986). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol55/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Invitation to Commit Fraud: Secret Destruction of Joint Tenant Survivorship Rights Cover Page Footnote * Professor of Law, Syracuse University. I wish to thank Lisa Gayle Bradley, Esq. for several helpful suggestions and for her able assistance in the preparation of this Article This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol55/iss2/2 AN INVITATION TO COMMIT FRAUD: SECRET DESTRUCTION OF JOINT TENANT SURVIVORSHIP RIGHTS SAMUEL M. FETTERS* INTRODUCTION JOINT tenancy is the most popular form of spousal residential prop- erty ownership in the United States.' Indeed, it is safe to say that * Professor of Law, Syracuse University. I wish to thank Lisa Gayle Bradley, Esq. for several helpful suggestions and for her able assistance in the preparation of this Article. 1. See E. -

Water Case 00-296

IN THE SUPREME COURT, STATE OF WYOMING 2002 WY 89 APRIL TERM, A.D. 2002 June 14, 2002 IN RE: THE GENERAL ADJUDICATION OF ) ALL RIGHTS TO USE WATER IN THE ) BIG HORN RIVER SYSTEM AND ALL ) OTHER SOURCES, STATE OF WYOMING, ) ) JACK APPLEBY, BRAD BATH, JIM BULINE, ) LEAH HEATHMAN, HORNECKER LIVESTOCK, ) INC., RALPH HORNECKER, TIM SCHELL, ) RALPH URBIGKIT, RALPH F. “RUSTY” and ) KATHY URBIGKIT, and DONALD VAN RIPER, ) ) No. 00-296 Appellants ) (Petitioners). ) Appeal from the District Court of Washakie County The Honorable Gary P. Hartman, Judge Representing Appellants: Sky D Phifer of Phifer Law Office, Lander, Wyoming Representing State of Wyoming: Thomas J. Davidson, Deputy Attorney General, Water and Natural Resources Division; Keith S. Burron, Special Assistant Attorney General, of Associated Legal Group, LLC, Cheyenne, Wyoming; and Brian C. Shuck, Special Assistant Attorney General, of Dray, Thomson & Dyekman, P.C., Cheyenne, Wyoming Representing Northern Arapaho Tribe: Richard M. Berley of Ziontz, Chestnut, Varnell, Berley & Slonim, Seattle, Washington Representing Eastern Shoshone Tribe: John Schumacher of Law Office of John Schumacher, Ft. Washakie, Wyoming Representing United States of America: John C. Cruden, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Environment & Natural Resources Division; John R. Green, Interim United States Attorney, and Carol Statkus and Thomas Roberts, Assistant United States Attorneys, Cheyenne, Wyoming; Lynn Johnson, Sean Donahue, and Jeffrey C. Dobbins, Attorneys, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.; and Richard Aldrich, Field Solicitor, Office of the Solicitor, United States Department of the Interior, Billings, Montana Before LEHMAN, C.J.; GOLDEN, KITE, and VOIGT, JJ.; and E. JAMES BURKE, D.J. NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in Pacific Reporter Third. -

Advanced Mineral Conveyancing and Title Issues - Part 1

Advanced Mineral Conveyancing By Sheryl L Howe Scott L Turner Welborn Sullivan Meek & Tooley, P.C. Denver Paper 1 SHERYL L. HOWE is an attorney with the Denver law firm of Welborn Sullivan Meek 85 Tooley, P.C., where her practice focuses on oil and gas, including title, transactions, and royally issues, along with a variety of other real property matters. She has practiced law in Denver since 1982 and has worked on oil and gas and natural resources matters throughout her legal career. Ms. Howe received her B.A. with honors from the University of Iowa in 1979. She attended the University of Colorado Law School and received her Juris Doctor in 1982. She is licensed to practice iaw in Colorado and Wyoming. SCOTT TURNER is an associate with Welborn Sullivan Meek 85 Tooley, P.C. in Denver, Colorado. Since joining the Firm in 2010, his practice focuses on title examination, oil and gas transactional work, and business and real estate services. Scott received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Indiana University with distinction in 1998 and then worked as a business and information technology consultant with Accenture, LLP for seven years in locales throughout the United States and abroad. Scott then attended the University of Colorado Law School, where he served as the Technical Production Editor of the Colorado Law Review. Upon graduation, Scott began his legal career as a real estate and business transactional attorney with a small law firm based in Denver and Vail, Colorado. Scott is an active member of the Colorado, Wyoming, and American Bar Associations. -

Tenancy by the Entirety in North Carolina Robert E

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 41 | Number 1 Article 8 12-1-1962 Tenancy by the Entirety in North Carolina Robert E. Lee Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert E. Lee, Tenancy by the Entirety in North Carolina, 41 N.C. L. Rev. 67 (1962). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol41/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TENANCY BY THE ENTIRETY IN NORTH CAROLINA* ROBERT E. LEEf NATURE OF TENANCY BY THE ENTIRETY Where real property is conveyed by deed or by will to two persons who are at the time husband and wife, a "tenancy by the entirety" is created. Sometimes it is referred to as an "estate by the entirety." The husband and wife take the whole estate as one person. Each has the whole; neither has a separate estate or interest; but the survivor, whether husband or wife, is entitled to the entire estate, and the right of the survivor cannot be defeated by the other's conveyance of the property by deed or will to a stranger. The title to the land cannot be conveyed during the existence of the marriage without the signature of both the husband and the wife. Neither tenant can defeat or in any way affect the right of survivorship of the other. -

Tenancy by the Entireties and Creditors Rights in Maryland Bridgewater M

Maryland Law Review Volume 9 | Issue 4 Article 1 Tenancy by the Entireties and Creditors Rights in Maryland Bridgewater M. Arnold Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Bridgewater M. Arnold, Tenancy by the Entireties and Creditors Rights in Maryland, 9 Md. L. Rev. 291 (1948) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol9/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maryland Law Review VOLUME IX FALL, 1948 NumBER 4 TENANCY BY THE ENTIRETIES AND CREDITORS RIGHTS IN MARYLAND By BRIDGEWATER M. ARNOLD* Maryland is one of the states in the Union which has preserved and protected the common law estate of tenancy by the entireties. In Marbury v. Cole,' Judge Alvey said: "By the common law of England, which is the law of this State, except where it has been changed or modified by statute, a conveyance to husband and wife does not constitute them joint tenants, nor are they tenants in common. They are in the contemplation of the common law, but one person, and hence they take, not by moieties, but the entirety. They are each seised of the entirety, and the survivor takes the whole. As stated by Blackstone, 'husband and wife being con- sidered as one person in law, they cannot take the estate by moieties, but both are seized of the entirety, per tout, et non per my; the consequence of which is, that neither the husband nor the wife can dispose of any part without the assent of the other, but the whole must remain to the survivor.' 2 Bl.