On Cowbells in Rock Anthems (And Property in IP): a Review of Justifying Intellectual Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

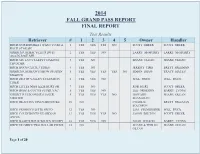

Fall Grand Pass Report Final Report

2014 FALL GRAND PASS REPORT FINAL REPORT Test Results Retriever # 1 2 3 4 5 Owner Handler HRCH NORTHFORKS I WANT TO BE A 1 YES YES YES NO SCOTT GREER SCOTT GREER ROCK STAR SH GRHRCH UH MAC'S LET'S DO IT 2 YES YES NO LARRY McMURRY LARRY McMURRY AGAIN JOSIE MH HRCH UH LUCY'S LEFTY DAKOTA 3 YES NO SHANE OLEAN SHANE OLEAN THUNDER HRCH BOO'S CLICK 3 TIMES 4 YES NO JEREMY TIMS BRETT FREEMAN GRHRCH UH SHAW'S SHOW STOPPIN' 5 YES YES YES YES NO SIMON SHAW TRACY HAYES SHADOW HRCH DEATH VALLEY'S CLEMSON 6 YES YES NO WILL PRICE WILL PRICE TIGER HRCH LITTLE MISS IZZIE HURT SH 7 YES NO ROB HURT SCOTT GREER HRCH BOSS & COCO'S SUPER VAC 8 YES YES NO LEE ORGERON BARRY LYONS GRHRCH UH BOOMER'S JAGER 9 YES YES YES NO HOWARD SHANE OLEAN MEISTER SHANAHAN HRCH DEACON'S VINEYARD DUKE 10 NO CHARLIE BRETT FREEMAN SOLOMON HRCH FROGGY'S LITTE FRITO 12 YES NO LISA STEMBRIDGE WILL PRICE HRCH COLDFRONTS GUARDIAN 13 YES YES YES NO JASON BELTON SCOTT GREER ANGEL HRCH BASIC'S ROUX WILD'N WOODY 14 YES YES NO NOAH WILSON BARRY LYONS HRCH UH SDK'S TWO DOLLAR PISTOL 15 NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN Page 1 of 20 HRCH ACADEMY'S HIGHWAY JUNKIE 16 YES YES YES NO DEREK & MELINDA BRETT FREEMAN RANDLE HRCH MEGAN'S BLACK ROSE 17 NO MARSHA HINCHER TRACY HAYES HRCH BULLET'S BIG TRIGGER 18 YES YES YES YES YES BRIAN SULLIVAN WILL PRICE HRCH SPOOKS TIMBER TIN LIZZY 19 YES YES YES NO WADE OLIVER SCOTT GREER HRCH BLUE'S & ROUX'S RAJIN 20 YES YES NO GLENN POST BARRY LYONS PUNKIN HRCH SDK'S MORE COWBELL 21 YES YES YES NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN HRCH ACADEMY'S DO WHAT I DO -

Aes 143Rd Convention Program October 18–21, 2017

AES 143RD CONVENTION PROGRAM OCTOBER 18–21, 2017 JAVITS CONVENTION CENTER, NY, USA The Winner of the 143rd AES Convention To be presented on Friday, Oct. 20, Best Peer-Reviewed Paper Award is: in Session 15—Posters: Applications in Audio A Statistical Model that Predicts Listeners’ * * * * * Preference Ratings of In-Ear Headphones: Session P1 Wednesday, Oct. 18 Part 1—Listening Test Results and Acoustic 9:00 am – 11:00 am Room 1E11 Measurements—Sean Olive, Todd Welti, Omid Khonsaripour, Harman International, Northridge, SIGNAL PROCESSING CA, USA Convention Paper 9840 Chair: Bozena Kostek, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland To be presented on Thursday, Oct. 18, in Session 7—Perception—Part 2 9:00 am P1-1 Generation and Evaluation of Isolated Audio Coding * * * * * Artifacts—Sascha Dick, Nadja Schinkel-Bielefeld, The AES has launched an opportunity to recognize student Sascha Disch, Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated members who author technical papers. The Student Paper Award Circuits IIS, Erlangen, Germany Competition is based on the preprint manuscripts accepted for the Many existing perceptual audio codec standards AES convention. define only the bit stream syntax and associated decod- A number of student-authored papers were nominated. The er algorithms, but leave many degrees of freedom to the excellent quality of the submissions has made the selection process encoder design. For a systematic optimization of encod- both challenging and exhilarating. er parameters as well as for education and training of The award-winning student paper will be honored during the experienced test listeners, it is instrumental to provoke Convention, and the student-authored manuscript will be consid- and subsequently assess individual coding artifact types ered for publication in a timely manner for the Journal of the Audio in an isolated fashion with controllable strength. -

More Cowbell: a Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations Lt Col Will Atkins, USAF Lt Col Donghyung Cho, ROK MAJ Sean Yarroll, USA

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL - FEATURE More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations LT COL WILL ATKINS, USAF LT COL DONGHYUNG CHO, ROK MAJ SEAN YARROLL, USA Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. To put it simply, we need to worry a lot less about how to communicate our actions and much more about what our actions communicate. —Former Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm Michael G. Mullen, August 2009 Introduction In a popular “Saturday Night Live” skit from 2000, despite the cowbell depicted as an afterthought in a fully integrated band, the audience learns a valuable lesson on the importance of “more cowbell.”1 To continue the metaphor, the cowbell has never been and will never be the primary line of effort in the band. But the cow- bell permeates throughout the music, often tying the entire performance together. Such is the fate of information operations in a joint environment, often consid- 20 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL SUMMER 2020 More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations ered a “second- class citizen as a source of nonlethal effects, an afterthought bolt- on to fires, or worse.”2 On the contrary, information operations is often the capa- bility that binds joint operations together to make it successful. -

The Long Tail / Chris Anderson

THE LONG TAIL Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More Enter CHRIS ANDERSON To Anne CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Introduction 1 1. The Long Tail 15 2. The Rise and Fall of the Hit 27 3. A Short History of the Long Tail 41 4. The Three Forces of the Long Tail 52 5. The New Producers 58 6. The New Markets 85 7. The New Tastemakers 98 8. Long Tail Economics 125 9. The Short Head 147 iv | CONTENTS 10. The Paradise of Choice 168 11. Niche Culture 177 12. The Infinite Screen 192 13. Beyond Entertainment 201 14. Long Tail Rules 217 15. The Long Tail of Marketing 225 Coda: Tomorrow’s Tail 247 Epilogue 249 Notes on Sources and Further Reading 255 Index 259 About the Author Praise Credits Cover Copyright ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book has benefited from the help and collaboration of literally thousands of people, thanks to the relatively open process of having it start as a widely read article and continue in public as a blog of work in progress. The result is that there are many people to thank, both here and in the chapter notes at the end of the book. First, the person other than me who worked the hardest, my wife, Anne. No project like this could be done without a strong partner. Anne was all that and more. Her constant support and understanding made this possible, and the price was significant, from all the Sundays taking care of the kids while I worked at Starbucks to the lost evenings, absent vacations, nights out not taken, and other costs of an all-consuming project. -

October 30, 2020 Vol

Love and sacrifice See our annual Religious Vocation Supplement, pages 1B-12B. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com October 30, 2020 Vol. LXI, No. 5 75¢ Senate confirms ‘God, send Amy Coney me a good Barrett to the Supreme Court Catholic girl’ WASHINGTON (CNS)—A divided Senate, in a 52-48 vote, confirmed Amy Coney Barrett as a justice for the Supreme Court on the evening of Oct. 26, and soon afterward she was sworn in by Justice Clarence Thomas at a White House ceremony. “The oath that I’ve solemnly taken tonight means at its core that I will do my Justice Amy Coney job without any fear or Barrett favor, and that I will Renae and Jon do so independently of Schoening are the both the political branches and of my own first recipients of the preferences. I love the Constitution and the archdiocese’s Water democratic republic that it establishes, and I into Wine Award. will devote myself to preserving it,” Barrett Named in honor of said after the outdoor ceremony. Jesus’ first public The 48-year old, who has been on the miracle at the wedding Chicago-based U.S. Court of Appeals for feast of Cana, the the 7th Circuit since 2017, said it was award recognizes a privilege to be asked to serve on the extraordinary efforts Supreme Court. She said she was “truly for marriage and family honored and humbled” to be stepping into ministry. (Submitted photo) this role, which is a lifetime appointment. Barrett is now the 115th justice for the court, replacing Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died on Sept. -

Saturday Night : a Backstage History of Saturday Night Live Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SATURDAY NIGHT : A BACKSTAGE HISTORY OF SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Doug Hill | 588 pages | 25 Aug 2014 | Untreed Reads Publishing | 9781611877090 | English | none Saturday Night : A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live PDF Book If you love the show, or even if you like the show, I can't imagine how you wouldn't enjoy this book. Stevie Nicks. Male writers have been known to pee in a cup or jar in their office instead of going to the bathroom. The Commodores. Peter Gabriel. By clicking "Sign Up" you are agreeing to our privacy policy and confirming that you are 13 years old or over. Chris Farley. If you want to know why and how Saturday Night Live came to be…this is the book. In , she appeared as a musical guest for the third episode of season 6 of Saturday Night Live. Something fruity and frozen. There was great background information on some of the most famous and infamous sketches and recurring characters from the early days of SNL. The Belushi stories. Our award-winning website offers reliable, easy-to-understand explanations about how the world works. Some of the seats used by the studio audience are old seats from Yankee Stadium. I found it to be an interesting read, even if none of the people involved were especially sympathetic. Pumpkin Spiced Latte. This English musician has won 3 Grammys and been nominated for Each successive star has their turn as second banana throwing jealous tantrums as they wait for the current stand out to leave the show and clear their way to SNL glory. -

Spring Convention 2017 Compendium

COMPENDIUM OF MATERIALS 100 Years of Excellence 2017 annual convention and legislative summit APRIL MARRIOTT 23-26 WARDMAN 2017 PARK Paying a Price Even When Innocent? No matter how diligently we work on behalf of our litigation clients, our success can be constrained when clients don’t have a complete, searchable project record. With proper procedures and technology in place there is no longer an excuse to live with this risk.” — Brent Gurney Partner at WilmerHale Attend this ACEC Convention session and visit Newforma at booth #213 No Disputing It: Monday April 24, 2017 Brent Gurney, Risk Mitigation Strategies 2:15-3:30 pm Partner at WilmerHale Too often firms are unfairly held accountable for problems because the evidence absolving them cannot be located. WilmerHale's global team of This panel discussion features firm principals and an nearly 500 litigators and experienced litigator sharing insights into ways to protect your controversy professionals handles highly complex and sensitive business. The discussion will emphasize best practices in matters in all aspects of litigation managing email and other project data. and dispute resolution. Learn more, and add to your calendar: newforma.com/acec-risk-mitigation Sponsored by www.newforma.com © 2016 Newforma, Inc. Newforma is a registered trademark of Newforma, Inc., in the United States and in other countries. All other brands or products are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. THE FUTURE OF INFRASTRUCTURE IS HERE Sunday, April 23 - Tuesday, April 25 Experience -

2017 AAF Winners Book.Pdf

COVER STATIC 2017 WINNER’S BOOK THANKS TO EVERYONE THAT ENTERED THE 2017 NASHVILLE ADDY AWARDS: Accent Media / Jive! A Goldner Associates Parachute Media Printworks Studio Goodwill Industries of Middle Paramore Digital Agency Aloompa Tennessee Powell Creative, LLC American Addiction Centers GS&F Proof Branding Barker & Christol Advertising Halangarde Pictures Pyxl BAUER | ASKEW Architecture Identity Visuals redpepper Big Machine Label Group iostudio Sharisse Steber Design Bill Hudson Agency Joe Hash Snapshot Interactive Birdsong Creative, Inc. KellyGirl Video ST8MNT Bob Delevante Studios knapptimecreative Stefanie Cobb Boyden & Youngblutt Lewis Communications | Studio Haus Nashville Brookdale Creative Tennessee Department of Carden Illustration LifeWay Christian Resources Economic and Community Conversion Interactive Lithographics, Inc. Development Country Music Hall of Fame Locomotion Creative The Buntin Group and Museum Metacake The Community Foundation of Delevante Creative Nashville Music City Center Middle Tennessee DNA Creative Nossi College of Art The International Offices DVL Seigenthaler NovaCopy The Stamberger Company Evergreen Life Services Onlife Health Thomas Nelson FlyteVu OUTFRONT Media Tuck-Hinton Architects FoxFuel Creative Paisley Pen Creative VNO Design Freelancer Pancake’s House, LLC Zehnder Communications COMMITTEE SPECIAL THANKS Joey Amato – AAF Nashville President Athens Paper: Bill Garvey, Don Jenkins Ben Thomas – ADDY Event Chair DVL Seigenthaler: Jimmy Chaffin Michael Hutzel – Creative Chair Francis Communications: -

The Stepford Justices": the Need for Experiential Diversity on the Roberts Court

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 60 Number 4 2007 "The Stepford Justices": The Need for Experiential Diversity on the Roberts Court Timothy P. O'Neill John Marshall Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Timothy P. O'Neill, "The Stepford Justices": The Need for Experiential Diversity on the Roberts Court, 60 OKLA. L. REV. 701 (2007), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol60/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE STEPFORD JUSTICES”: THE NEED FOR EXPERIENTIAL DIVERSITY ON THE ROBERTS COURT TIMOTHY P. O’NEILL* Is it finally over? I mean the Roberts Court’s “Era of Good Feeling.” Please, may we all stop singing Kumbaya1 and go back to being our irascible selves? Was it really less than two years ago when a sophisticated legal analyst such as Jeffrey Rosen could—with a straight face—provide this account of an interview with Chief Justice John Roberts: “[John] Marshall’s example had taught him, Roberts said, that personal trust in the chief justice’s lack of an ideological agenda was very important.”2 Or how about, “Roberts said he had not thought about the sources of his own interest in unity and consensus and bringing people together or whether there was anything in his upbringing that might account for it.”3 The final score of the 2006 Term? Out of seventy-two cases, the U.S. -

Saturday Night Live - the Best of Christopher Walken

Saturday Night Live - The Best of Christopher Walken I really like Christopher Walken about SNL.Coupled with Alec Baldwin's initially shows, almost all of Ben Hanks', Sara Malkovich's, and especially Kevin Spacey's, I feel they are the very best shows actually. However this Disc let down me. Of "The Continental" sketches, easily the funniest and continues to be the first one they will ever have.And it's never here. The two additional Continentals through the indicate and, inside the Accessories, there exists yet another in which shows equally what the S.E.Sixth is v. camera perceives precisely what the crowd recognizes (causing this to be DVD worthy of seeing). The widely used "Cowbell" sketch is on the Best of Can Ferrell (quantity 1).The particular "Lovers" make, which I've certainly not ended up keen on, seems about volume 3 associated with Will Ferrell's Finest. Therefore, for sure Saturday night live lovers, spending budget these types of. A further gripe We have is the fact that substandard images via newer reveals seem (such as the Lifeboat along with Centaur paintings) when before blueprints appear to have been dismissed.Joe as Assortment Go some sort of overdue 80's indicate appeared to be significantly really nice. Like with Is going to Ferrell A couple of, truly doesn't feel as if any individual actually labored quite difficult putting this particular collection with each other.So i definitely don't think it's just a matter of flavor. But the Fonzie make from the Accessories is a plus. -

Progress 2013 Annual Report the Michael J

PROGRESS 2013 ANNUAL REPORT THE MICHAEL J. FOX FOUNDATION FOR PArkinson’s RESEARCH The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an aggressively funded research agenda and to ensuring the development of improved therapies for those living with Parkinson’s today. PROGRESS 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Foreword by Michael J. Fox 3 Empowering Patients 4 Key Achievements 6 Progress in Treatments 8 2013 In Pictures 11 2013 Donor Listing 15 The Robert A. Pritzker Prize for Leadership in Parkinson’s Research 28 Remembering Al Glickman 33 2013 Team Fox Donor Listing 41 2013 Financial Highlights 44 2013 Canadian Financial Highlights 47 Boards and Councils 2 FOREWORD BY MICHAEL J. FOX Dear Friend, This Foundation began as an answer to a question that drives us every day. Why can’t we cure Parkinson’s disease? As you’ll read in this report, today we believe we’re closer than ever to the answer we’ve always known is out there. No single individual or organization could do the work of speeding a cure for Parkinson’s. In these pages, you will hear from some of the voices of those who are helping us get closer to our goal — Foundation leaders, researchers, Board members, patients and fundraisers who bring unparalleled energy, passion and creativity to our mission. Since the very beginning, Parkinson’s patients have been at the heart of every decision we make. Working hand-in-hand with our community inspires and motivates us. We’ve started this report with an update on our activities to build on and grow the patient empowerment that’s key to getting us where we need to go.