The Stepford Justices": the Need for Experiential Diversity on the Roberts Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

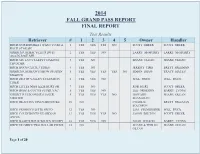

Fall Grand Pass Report Final Report

2014 FALL GRAND PASS REPORT FINAL REPORT Test Results Retriever # 1 2 3 4 5 Owner Handler HRCH NORTHFORKS I WANT TO BE A 1 YES YES YES NO SCOTT GREER SCOTT GREER ROCK STAR SH GRHRCH UH MAC'S LET'S DO IT 2 YES YES NO LARRY McMURRY LARRY McMURRY AGAIN JOSIE MH HRCH UH LUCY'S LEFTY DAKOTA 3 YES NO SHANE OLEAN SHANE OLEAN THUNDER HRCH BOO'S CLICK 3 TIMES 4 YES NO JEREMY TIMS BRETT FREEMAN GRHRCH UH SHAW'S SHOW STOPPIN' 5 YES YES YES YES NO SIMON SHAW TRACY HAYES SHADOW HRCH DEATH VALLEY'S CLEMSON 6 YES YES NO WILL PRICE WILL PRICE TIGER HRCH LITTLE MISS IZZIE HURT SH 7 YES NO ROB HURT SCOTT GREER HRCH BOSS & COCO'S SUPER VAC 8 YES YES NO LEE ORGERON BARRY LYONS GRHRCH UH BOOMER'S JAGER 9 YES YES YES NO HOWARD SHANE OLEAN MEISTER SHANAHAN HRCH DEACON'S VINEYARD DUKE 10 NO CHARLIE BRETT FREEMAN SOLOMON HRCH FROGGY'S LITTE FRITO 12 YES NO LISA STEMBRIDGE WILL PRICE HRCH COLDFRONTS GUARDIAN 13 YES YES YES NO JASON BELTON SCOTT GREER ANGEL HRCH BASIC'S ROUX WILD'N WOODY 14 YES YES NO NOAH WILSON BARRY LYONS HRCH UH SDK'S TWO DOLLAR PISTOL 15 NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN Page 1 of 20 HRCH ACADEMY'S HIGHWAY JUNKIE 16 YES YES YES NO DEREK & MELINDA BRETT FREEMAN RANDLE HRCH MEGAN'S BLACK ROSE 17 NO MARSHA HINCHER TRACY HAYES HRCH BULLET'S BIG TRIGGER 18 YES YES YES YES YES BRIAN SULLIVAN WILL PRICE HRCH SPOOKS TIMBER TIN LIZZY 19 YES YES YES NO WADE OLIVER SCOTT GREER HRCH BLUE'S & ROUX'S RAJIN 20 YES YES NO GLENN POST BARRY LYONS PUNKIN HRCH SDK'S MORE COWBELL 21 YES YES YES NO SHANE & TERI JO SHANE OLEAN OLEAN HRCH ACADEMY'S DO WHAT I DO -

Conflicts of Interest in Bush V. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 2003 Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K. Neumann Jr. Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Richard K. Neumann Jr., Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally?, 16 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 375 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? RICHARD K. NEUMANN, JR.* On December 9, 2000, the United States Supreme Court stayed the presidential election litigation in the Florida courts and set oral argument for December 11.1 On the morning of December 12-one day after oral argument and half a day before the Supreme Court announced its decision in Bush v. Gore2-the Wall Street Journalpublished a front-page story that included the following: Chief Justice William Rehnquist, 76 years old, and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, 70, both lifelong Republicans, have at times privately talked about retiring and would prefer that a Republican appoint their successors.... Justice O'Connor, a cancer survivor, has privately let it be known that, after 20 years on the high court,'she wants to retire to her home state of Arizona ... -

Aes 143Rd Convention Program October 18–21, 2017

AES 143RD CONVENTION PROGRAM OCTOBER 18–21, 2017 JAVITS CONVENTION CENTER, NY, USA The Winner of the 143rd AES Convention To be presented on Friday, Oct. 20, Best Peer-Reviewed Paper Award is: in Session 15—Posters: Applications in Audio A Statistical Model that Predicts Listeners’ * * * * * Preference Ratings of In-Ear Headphones: Session P1 Wednesday, Oct. 18 Part 1—Listening Test Results and Acoustic 9:00 am – 11:00 am Room 1E11 Measurements—Sean Olive, Todd Welti, Omid Khonsaripour, Harman International, Northridge, SIGNAL PROCESSING CA, USA Convention Paper 9840 Chair: Bozena Kostek, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland To be presented on Thursday, Oct. 18, in Session 7—Perception—Part 2 9:00 am P1-1 Generation and Evaluation of Isolated Audio Coding * * * * * Artifacts—Sascha Dick, Nadja Schinkel-Bielefeld, The AES has launched an opportunity to recognize student Sascha Disch, Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated members who author technical papers. The Student Paper Award Circuits IIS, Erlangen, Germany Competition is based on the preprint manuscripts accepted for the Many existing perceptual audio codec standards AES convention. define only the bit stream syntax and associated decod- A number of student-authored papers were nominated. The er algorithms, but leave many degrees of freedom to the excellent quality of the submissions has made the selection process encoder design. For a systematic optimization of encod- both challenging and exhilarating. er parameters as well as for education and training of The award-winning student paper will be honored during the experienced test listeners, it is instrumental to provoke Convention, and the student-authored manuscript will be consid- and subsequently assess individual coding artifact types ered for publication in a timely manner for the Journal of the Audio in an isolated fashion with controllable strength. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Charles Evans Whittaker Courthouse Room 1510 400 East 9Th Street Kansas City, MO 64106 E-MAIL

Updated 11/03 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Charles Evans Whittaker Courthouse Room 1510 400 East 9th Street Kansas City, MO 64106 www.mow.uscourts.gov http://ecf.mow.uscourts.gov E-MAIL ADDRESSES/TELEPHONE NUMBERS - AREA CODE 816 Chief Deputy Clerk - John Cisternino, 512-1851, [email protected] Automated Case Information (24 hours) 512-5110; 1-888-205-2527 Filing requirements 512-1800 341 meeting schedules - Judy Hale 512-1815, [email protected] Procedural Questions- Roberta Kostrow 512-1818, [email protected] FAX 512-1832 JUDGES Division 3 - Chief Judge Arthur B. Federman, Room 6552 512-1910 Judicial Assistant - Joan Brown 512-1911 Law Clerk - Donna Thalblum 512-1913 Courtroom Deputy - Sharon Stanley 512-1924 [email protected] FAX No. 512-1923 Division 2 - Judge Dennis R. Dow, Room 6562 512-1880 Judicial Assistant - Kerry Brown 512-1880 Law Clerk - Lori Locke 512-1886 Courtroom Deputy - Georgia Ann Tarwater 512-1894 [email protected] FAX No. 512-1893 Division 1 - Judge Jerry W. Venters, Room 6462 512-1895 Judicial Assistant -Arlene Wilbers 512-1896 Law Clerk - Ryan Johnson 512-1898 Courtroom Deputy - Jamie Hinkle 512-1909 [email protected] FAX No. 512-1908 Division 1, 2 and 3 Kansas City Chapter 13 cases Courtroom Deputy - Michele Blodig 512-1827 [email protected] APPENDIX 1-00 Appendix Page 1 AGENCIES ADDED TO ALL BANKRUPTCY MATRICES BY COURT Missouri Department of Revenue P.O. Box 475 Jefferson City, MO 65105-0475 DO NOT ADD DEBTOR OR DEBTOR’S ATTORNEY TO MAILING MATRIX FEDERAL AGENCIES THAT MUST BE ADDED TO MATRIX BY DEBTOR, IF APPLICABLE U.S. -

70 13Creightonlrev1057(1979-1980).Pdf (77.01Kb)

1057 INTRODUCTION Creighton Law Review is to be commended for instituting a survey, intended to be done annually, of the decisions of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Other law reviews have done this* and I think that those projects have been generally successful. The Eighth Circuit, of course, is a rich source of legal materi- als. The circuit, while perhaps not so celebrated as the Second, because of its location away from the Eastern Seaboard and the "name" law schools, has been a staunch and solid court since its founding, has enunciated federal law for a substantial portion of the Nation's heartland and (prior to 1929 when the Tenth Circuit was formed from it) for the Rocky Mountain area as well. The cir- cuit's geographical location, stretching from the Canadian border to the Louisiana line, lends variety and strengthens its Bar in a way not enjoyed by any other circuit except, perhaps to a degree, the Sixth. The Eighth Circuit has produced its share of Justices of the Supreme Court-David Josiah Brewer, Willis Van Devanter, and Charles Evans Whittaker-by elevation from its own ranks and others-Samuel Freeman Miller, Pierce Butler, Wiley Blount Rut- ledge, and Warren E. Burger-from the States that it serves. There have been other equally distinguished figures of the law upon its own bench: the two Sanborns (Walter H. and John B.), Kimbrough Stone, William S. Kenyon, Wilbur F. Booth, Archibald K. Gardner, Harvey M. Johnsen, Martin D. Van Oosterhout, in years past. There are others yet alive, and there will be more in the years yet to come. -

2001 Newsletter

Historical Society News The present is the living sum-total of the whole past - Thomas Carlyle The Historical Society of the United States Courts in the Eighth Circuit Volume Eight 2001 Blackmun Rotunda IN THIS ISSUE... he Blackmun Rotunda on the 27th floor of the Thomas F. Eagleton Courthouse in St. Blackmun Rotunda ............................. 1 TLouis is dedicated to the memory and legacy Eighth Circuit History Project ................... 3 of Justice Harry A. Blackmun. Justice Blackmun Court Historians ............................... 3 served as a Supreme Court Justice from 1970 until State and Federal Court Historical Societies Annual his retirement in 1994. Before that, he served as a Meeting ..................................... 4 judge for the United States Court of Appeals for Around the Circuit ............................. 5 the Eighth Circuit from 1959 until 1970. While he Arkansas ............ 5 is best known for his role on the Supreme Court, Arkansas Branch Near Completion of Judicial he also wrote many important decisions as an Biographies Project ........ 5 Eighth Circuit Judge. The Rotunda now houses a Iowa ........................................ 5 permanent display describing Justice Blackmun’s John F. Dillon Essay Competition ........... 5 Minnesota ................................... 6 life from the time of his childhood through his Judge to Justice: from the Eighth Circuit to the retirement from the Supreme Court. U.S. Supreme Court ....................... 6 Missouri .................................... 6 Limbaugh -

Protecting Citizen Journalists: Why Congress Should Adopt a Broad Federal Shield Law

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Protecting Citizen Journalists: Why Congress Should Adopt a Broad Federal Shield Law Stephanie B. Turner* INTRODUCTION On August 1, 20o6, a federal district judge sent Josh Wolf, a freelance video journalist and blogger, to prison.' Wolf, a recent college graduate who did not work for a mainstream media organization at the time, captured video footage of an anti-capitalist protest in California and posted portions of the video on his blog.2 As part of an investigation into charges against protestors whose identi- ties were unknown, federal prosecutors subpoenaed Wolf to testify before a grand jury and to hand over the unpublished portions of his video.' Wolf re- fused to comply with the subpoena, arguing that the First Amendment allows journalists to shield their newsgathering materials.4 The judge disagreed, and, as * Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2012; Barnard College, B.A. 2009. Thank you to Adam Cohen for inspiration; to Emily Bazelon, Patrick Moroney, Natane Single- ton, and the participants of the Yale Law Journal-Yale Law & Policy Review student scholarship workshop for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts; and to Rebecca Kraus and the editors of the Yale Law & Policy Review for their careful editing. 1. See Order Finding Witness Joshua Wolf in Civil Contempt and Ordering Con- finement at 2, In re Grand Jury Proceedings to Joshua Wolf, No. CR 06-90064 WHA (N.D. Cal. 2006); Jesse McKinley, Blogger Jailed After Defying Court Orders, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 2, 2006, at A15. 2. For a detailed description of the facts of this case, see Anthony L. -

More Cowbell: a Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations Lt Col Will Atkins, USAF Lt Col Donghyung Cho, ROK MAJ Sean Yarroll, USA

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL - FEATURE More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations LT COL WILL ATKINS, USAF LT COL DONGHYUNG CHO, ROK MAJ SEAN YARROLL, USA Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. To put it simply, we need to worry a lot less about how to communicate our actions and much more about what our actions communicate. —Former Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm Michael G. Mullen, August 2009 Introduction In a popular “Saturday Night Live” skit from 2000, despite the cowbell depicted as an afterthought in a fully integrated band, the audience learns a valuable lesson on the importance of “more cowbell.”1 To continue the metaphor, the cowbell has never been and will never be the primary line of effort in the band. But the cow- bell permeates throughout the music, often tying the entire performance together. Such is the fate of information operations in a joint environment, often consid- 20 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL SUMMER 2020 More Cowbell: A Case Study in System Dynamics for Information Operations ered a “second- class citizen as a source of nonlethal effects, an afterthought bolt- on to fires, or worse.”2 On the contrary, information operations is often the capa- bility that binds joint operations together to make it successful. -

Open Chambers?

Michigan Law Review Volume 97 Issue 6 1999 Open Chambers? Richard W. Painter University of Illinois College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Richard W. Painter, Open Chambers?, 97 MICH. L. REV. 1430 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol97/iss6/11 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPEN CHAMBERS? Richard W. Painter* CLOSED CHAMBERS: THE FIRST EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE EPIC STRUGGLES INSIDE THE SUPREME COURT. By Edward LazarU,S. New York: Times Books. 1998. Pp. xii, 576. $27.50. Edward Lazarus1 has written the latest account of what goes on behind the marble walls of the Supreme Court. His book is not the first to selectively reveal confidential communications between the Justices and their law clerks. Another book, Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong's The Brethren2 achieved that distinction in 1979. Closed Chambers: The First Eyewitness Account of the Ep ic Strug gles Inside the Supreme Court, however, adds a new twist. Whereas The Brethren was written by journalists who persuaded former law clerks to breach the confidences of the Justices, Lazarus was himself a law clerk to Justice Harry Blackmun. -

The Long Tail / Chris Anderson

THE LONG TAIL Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More Enter CHRIS ANDERSON To Anne CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Introduction 1 1. The Long Tail 15 2. The Rise and Fall of the Hit 27 3. A Short History of the Long Tail 41 4. The Three Forces of the Long Tail 52 5. The New Producers 58 6. The New Markets 85 7. The New Tastemakers 98 8. Long Tail Economics 125 9. The Short Head 147 iv | CONTENTS 10. The Paradise of Choice 168 11. Niche Culture 177 12. The Infinite Screen 192 13. Beyond Entertainment 201 14. Long Tail Rules 217 15. The Long Tail of Marketing 225 Coda: Tomorrow’s Tail 247 Epilogue 249 Notes on Sources and Further Reading 255 Index 259 About the Author Praise Credits Cover Copyright ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book has benefited from the help and collaboration of literally thousands of people, thanks to the relatively open process of having it start as a widely read article and continue in public as a blog of work in progress. The result is that there are many people to thank, both here and in the chapter notes at the end of the book. First, the person other than me who worked the hardest, my wife, Anne. No project like this could be done without a strong partner. Anne was all that and more. Her constant support and understanding made this possible, and the price was significant, from all the Sundays taking care of the kids while I worked at Starbucks to the lost evenings, absent vacations, nights out not taken, and other costs of an all-consuming project. -

No. 19-1392 THOMAS E. DOBBS, State Health Officer

No. 19-1392 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ___________________ THOMAS E. DOBBS, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al., Petitioners, v. JACKSON WOMEN’S HEALTH ORGANIZATION, et al., Respondents. ___________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ___________________ BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE AFRICAN- AMERICAN, HISPANIC, ROMAN CATHOLIC AND PROTESTANT RELIGIOUS AND CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS AND LEADERS SUPPORTING PETITIONERS ___________________ Mathew D. Staver Counsel of Record Anita L. Staver Horatio G. Mihet Roger K. Gannam Daniel J. Schmid LIBERTY COUNSEL P.O. BOX 540774 Orlando, FL 32854 (407)875-1776|[email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................. iii INTEREST OF AMICI ............................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................................... 4 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 6 I. ABORTION GREW OUT OF AND REMAINS ROOTED IN EUGENICS IDEOLOGY THAT ELIMINATES “LESS DESIRABLE” RACES AND CERTAIN CLASSES OF PEOPLE TO EVOLVE A SUPERIOR HUMAN POPULATION. .............. 6 A. The Birth Control Movement, Abortion Advocacy, and Eugenics Are All Rooted In Social Darwinism and the Elimination of Undesirable Populations. .................................................. 7 B. The Eugenics Movement’s Racist Roots. 10 C. A Dark Stain Upon This Court, Buck v. Bell Legitimized the Eugenics Movement.