Advanced Mineral Conveyancing and Title Issues - Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

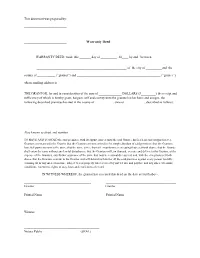

Warranty Deed

This document was prepared by: __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ Warranty Deed WARRANTY DEED, made this _______ day of __________, 20____ by and between _______________________________________________________ of the city of __________and the county of ___________ (“grantor”) and ___________________________________________________ (“grantee”) whose mailing address is ________________________________________________________________ THE GRANTOR, for and in consideration of the sum of ______________ DOLLARS ($_________) the receipt and sufficiency of which is hereby grant, bargain, self and convey unto the grantee his/her heirs and assigns, the following described premises located in the county of ___________, state of ____________, described as follows: Also known as street and number ______________________________________________________ TO HAVE AND TO HOLD the said premises, with its appurtenances unto the said Grantee his/her heirs and assigns forever. Grantors covenant with the Grantee that the Grantors are now seized in fee simple absolute of said premises; that the Grantors have full power to convey the same; that the same is free from all encumbrances excepting those set forth above; that the Grantee shall enjoy the same without any lawful disturbance; that the Grantors will, on demand, execute and deliver to the Grantee, at the expense of the Grantors, any further assurance of the same that may be reasonably required, and, with the exceptions set forth above, that the Grantors warrant to the Grantee and will defend for him/her all the said premises against every person lawfully claiming all or any interest in same, subject to real property taxes accrued by not yet due and payable and any other covenants, conditions, easements, rights of way, laws and restrictions of record. -

Leases and the Rule Against Perpetuities

LEASES AND THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES EDWIN H. ABBOT, JUNIOR of the Boston Bar INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule against perpetuities to leases. A leasehold estate has certain peculiari- ties which distinguish it, as a practical matter, from other estates in land. At common law it required no livery of seisin, and so could be created to begin in futuro. Although it is not an estate of freehold the duration of the estate may be practically unlimited-it may be for 999 years or even in perpetuity. The reversion after an estate for years is necessarily vested, no matter how long the term of the lease may be, yet the leasehold estate is generally terminable at an earlier time upon numerous conditions subsequent, defined in the lease. In other words the leasehold estate determines without condition by the effluxion of the term defined in the lease but such termination may be hastened by the happening of one or more conditions. The application of the rule against perpetuities to such an estate presents special problems. The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule to the creation, termination and renewal of leases; and also its effect upon options inserted in leases. II CREATION A leasehold estate may be created to begin in futuro, since livery of seisin was not at common law required for its creation. Unless limited by the rule a contingent lease might be granted to begin a thousand years hence. But the creation of a contingent estate for years to begin a thousand years hence is for practical reasons just as objectionable as the limitation of a contingent fee to begin at such a remote period by means of springing or shifting uses, or by the device of an execu- tory devise. -

Supplementary Conveyancing Questionnaire

Supplementary Conveyancing Questionnaire (To be completed if you have answered YES to 9d) Should you have insufficient space to answer any questions, please continue on your own HEADED notepaper Please note that this questionnaire forms part of your proposal for professional indemnity insurance and you are reminded of the importance of the notes and declaration on the proposal, which also applies to this questionnaire. LLP 682 - Jul 12 Important note regarding the completion of this proposal form. 1. Disclosure Any “material fact” must be disclosed to insurers - A “material fact” is any information which may influence the judgement of a prudent insurer in deciding whether to accept the risk and if so, on what terms. Any “material change” must be disclosed to insurers. - A “material change” is any material fact which arises on renewal or during the currency of the policy that has not previously been disclosed as a material fact. Examples of material changes to material facts include: • Fraud on the part of any of the Partners and Employees • A change in the composition of the firm's practice • Mergers and Acquisitions with other firms • Conversion to a Limited Liability Partnership If you are unsure whether a fact or change is material or not, you should disclose it. Failure to provide all “material facts” and/or notify all “material changes” may cause the contract of insurance to be void from inception i.e. your insurers will return the premium and there will be no cover for any claims made under the policy. 2. Presentation This proposal form must be completed by an authorised individual or principal of the firm. -

Law and Practice

GLOBAL PRACTICE GUIDEs Definitive global law guides offering comparative analysis from top ranked lawyers USA Regional Real Estate Montana Crowley Fleck PLLP chambersandpartners.com 2018 MONTANA LAW AND PRACTICE: p.3 Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP The ‘Law & Practice’ sections provide easily accessible information on navigating the legal system when conducting business in the jurisdic- tion. Leading lawyers explain local law and practice at key transactional stages and for crucial aspects of doing business. LAW AND PRACTICE MONTANA Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP Authors: Kevin Heaney, Matthew McLean, Michael Tennant, Alissa Chambers Law and Practice Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP CoNTENTS 1. General p.5 4. Planning and Zoning p.11 1.1 Main Substantive Skills p.5 4.1 Legislative and Governmental Controls Applicable 1.2 Most Significant Trends p.5 to Design, Appearance and Method of Construction p.11 1.3 Impact of the New US Tax Law Changes p.6 4.2 Regulatory Authorities p.11 2. Sale and Purchase p.6 4.3 Obtaining Entitlements to Develop a New 2.1 Ownership Structures p.6 Project p.11 2.2 Important Jurisdictional Requirements p.6 4.4 Right of Appeal Against an Authority’s 2.3 Effecting Lawful and Proper Transfer of Title p.6 Decision p.12 2.4 Real Estate Due Diligence p.6 4.5 Agreements with Local or Governmental 2.5 Typical Representations and Warranties for Authorities p.12 Purchase and Sale Agreements p.6 4.6 Enforcement of Restrictions on Development 2.6 Important Areas of Laws for Foreign Investors p.8 and Designated Use p.12 2.7 Soil Pollution and Environmental 5. -

The Myth of Strict Foreclosure

THE MYTH OF STRICT FORECLOSURE SHmLDON TEFF* YTHS in the field of mortgages are many and striking. One of the most striking is the assumption of American students that the English chancellor left the mortgagor virtually unprotected from his mortgagee. It is not diffitult to find the reasons for this assump- tion. In the colonial period of the country the Court of Chancery was in great disrepute., Time has removed much of the prejudice against doctrines of the chancellor, but in the field of mortgages the prejudice has continued. First, the English system of mortgages seems very primitive to American students. The struggle of junior mortgages to obtain the status of legal charges has confirmed the tradition that the English system of mortgages was very slow in developing, and the hocus-pocus of the long-term lease by which, under the 1925 legislation,2 the second mortgage emerged as a legal charge tended to confirm the prejudice. Surely under a system so primitive mortgagors could not have been adequately protected! The second reason for the prejudice is based upon the history of the American law of mortgages. For more than a century the trend of the American law has been toward greater protection for the debtor. Judges and legislators have joined in the effort to improve the position of the mortgagor and yet, as the d6bicle of the last decade shows, the present American system leaves the mortgagor without adequate protection. The position of mortgagors who did not have the benefit of the century's improvements must have been miserable indeed. -

1400 Co Ownership and Condominium

1400 CO-OWNERSHIP AND CONDOMINIUM Marshall E. Tracht Associate Professor, Hofstra University School of Law © Copyright 1999 Marshall E. Tracht Abstract Co-ownership refers to legal relations in which two or more entities have equal rights to the use and enjoyment of property. Co-ownership relationships may satisfy the preferences of some owners, and predefined categories of co-ownership, as opposed to contractually defined relations, may allow parties to satisfy these preferences at relatively low cost. However, shared ownership results in coordination and externality problems, which the law attempts to mitigate in numerous ways, including judicial oversight of ‘reasonableness’ (as in the law of waste) or fiduciary duties; ending the co-ownership relation (through the right of partition) or providing rules that seek to optimize the joint decision-making process (such as compulsory unitization). A major area of growth in shared ownership is in condominium developments, where entities own some property individually, while co-owning common facilities. This permits parties to take advantage of economies of scale and the joint provision of common goods. Condominium arrangements are governed by a combination of contract, statute and judicial law, and typically include democratic decision-making structures intended to minimize the sum of decision-making costs (gathering information, voting, and bargaining) and the cost of erroneous decisions. JEL classification: K11, P32, H41 Keywords: Cotenancy, Co-ownership, Condiminium, Cooperative, Communal Ownership 1. Introduction Co-ownership refers to legal relationships that entitle two or more entities to equal rights to the use and enjoyment of property. Although it most often arises in the context of real property, co-ownership may apply to any type of property. -

Water Law in Real Estate Transactions

Denver Bar Association Real Estate Section Luncheon November 6, 2014 Water Law in Real Estate Transactions by Paul Noto, Esq. [email protected] Prior Appropriation Doctrine • Prior Appropriation Doctrine – First in Time, First in Right • Water allocated exclusively based on priority dates • Earliest priorities divert all they need (subject to terms in decree) • Shortages of water are not shared • “Pure” prior appropriation in CO A historical sketch of Colorado water law • Early rejection of the Riparian Doctrine, which holds that landowners adjacent to a stream can make a reasonable use of the water flowing through your land. – This policy was ill-suited to Colorado and would have hindered growth, given that climate and geography necessitate transporting water far from a stream to make land productive. • In 1861 the Territorial Legislature provided that water could be taken from the streams to lands not adjacent to streams. • In 1872, the Colorado Territorial Supreme Court recognized rights of way (easements), citing custom and necessity, through the lands of others for ditches carrying irrigation water to its place of use. Yunker v. Nichols, 1 Colo. 551, 570 (1872) A historical sketch of Colorado water law • In 1876 the Colorado Constitution declared: – “The water of every natural stream, not heretofore appropriated, within the state of Colorado, is hereby declared to be the property of the public, and the same is dedicated to the use of the people of the state, subject to appropriation as hereinafter provided.” Const. of Colo., Art. XVI, Sec. 5. – “The right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied. -

1 Preventing Homelessness

PREVENTING HOMELESSNESS STATEMENT OF BEST PRACTICE IN JOINT WORKING BETWEEN RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL AND HOUSING ASSOCIATIONS (RSLs), PRIVATE LANDLORDS AND CREDITORS IN THE RENFREWSHIRE AREA. EVICTION PROTOCOL 1. INTRODUCTION This Statement of Best Practice aims to ensure that prevention of homelessness and dealing with evictions takes place in a non-discriminatory way and that appropriate support is available to all tenants/legal occupiers on an individual basis. The agreement relies on effective partnership working, built upon honesty, integrity, confidentiality and a willingness by all parties to prevent eviction and resultant homelessness. 2. BACKGROUND The prevention of homelessness, whatever the cause, is a key strategic aim of Renfrewshire Council. Section 11 of the Homelessness etc. (Scotland) Act 2003 places a duty on all Registered Social Landlords/private sector landlords* and creditors to notify the local authority of any repossession proceedings. The duty under Section 11 becomes a statutory requirement on 1st April 2009 (* Since April 2006 all private landlords letting property in Scotland have also had a duty to register with the Council.) This Statement of Best Practice sets out arrangements for the implementation of Section 11 to ensure that all tenants and legal occupants of dwellings in Renfrewshire have access to services which can provide advice and assistance in preventing homelessness occurring as a result of eviction or repossession due to rent or mortgage arrears, or other management grounds. As part of an ongoing restructure of homelessness services in Renfrewshire, a Prevention Team has been established. Within this team there are Homeless Prevention Officers who have a dedicated role to assist households threatened with homelessness. -

Types of Deeds Components of the Deed

Types of Deeds General Warranty • Warrants title against all defects in title, whether they arose before and after grantor took title. Special Warranty • Warrants title against the grantor’s own acts but not the acts of others. Quitclaim • No warranties. Conveys whatever interest/title that grantor has, which could be nothing. U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2008 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. Components of the Deed • Location of the property • Salutation • Grantor’s name and residence • Consideration, receipt of consideration, and method of payment • Granting grantee the property and grantee residence U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2008 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. 1 Components of the Deed Cont’d • Description of the property • Habendum (to-have-and-to-hold) • Warranty • Any limitation of title or the interest • Execution date and place • Execution • Acknowledgment (notary) U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2008 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. Warranties • Present • Covenant of seisin • Covenant of right to convey • Covenant against encumbrances • Future • Covenant of general warranty • Covenant of quiet enjoyment • Covenant of further assurances U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Violations of Zoning Ordinances, the Covenant Against Encumbrances, and Marketability of Title: How Purchasers Can Be Better Protected

VIOLATIONS OF ZONING ORDINANCES, THE COVENANT AGAINST ENCUMBRANCES, AND MARKETABILITY OF TITLE: HOW PURCHASERS CAN BE BETTER PROTECTED Jessica P. Wilde∗ I. INTRODUCTION Zoning ordinances function as an exercise of the government’s general police power, sustaining the enjoyment, health, and safety of the public. They are important in order to maintain property values and protect a neighborhood’s quality and environment.1 Zoning ordinances prevent people from using their property in a way that would make a neighborhood less enjoyable.2 State statutes often provide civil and criminal penalties for failing to comply with zoning ordinances.3 Noncompliance with existing ordinances may be of concern to a buyer who buys a parcel of land ∗ J.D. candidate, Touro Law Center, May 2007; B.S., Brigham Young University, May 2004. 1 See ROBERT H. NELSON, ZONING AND PROPERTY RIGHTS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN SYSTEM OF LAND USE REGULATION 11-12 (1977). 2 Id. They are often enacted for safety purposes; for example, a zoning ordinance prevents commercial use in a residential neighborhood or may require a permit or certificate of occupancy before a building is occupied. In addition, a zoning ordinance may be in the form of a building code, requiring that the building maintain certain requirements for fire code purposes. Ordinances serve an array of important functions in order to maintain the value and enjoyment of a neighborhood, as well as facilitate the safety and health of the public. 3 Adam Forman, Comment, What You Can’t See Can Hurt You: Do Latent Violations of a Restrictive Land Use Ordinance, Existing Upon Conveyance, Constitute a Breach of the Covenant Against Encumbrances? 64 ALB. -

False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note Goerge W

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Natural Law Forum 1-1-1956 False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note Goerge W. Constable Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constable, Goerge W., "False Natural Law: Professor Goble's Straw Man, The;Note" (1956). Natural Law Forum. Paper 9. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Law Forum by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FALSE NATURAL LAW: PROFESSOR GOBLE'S STRAW MAN To ALL WHO FOLLOW the trends here and abroad in legal philosophy, it has become apparent that the tide which has run so strongly against natural law theory for many decades, has now begun to turn. As the fatal emptiness in the heart of positivism becomes more exposed with each fresh assault upon freedom by evil ideologies and with every new example of antisocial individualism, the natural law position wins more attention and regains more of its ancient prestige.' For the natural law position, in the classical and Scholastic sense, is gradually revealing itself for what it is-as a strong central defense point between two extremes, seeking at once to secure for us proper individual freedoms and to impose upon us proper social duties.2 Significant in this turn of the tide is the article of George W. Goble entitled "Nature, Man and Law: The True Natural Law" (A.B.A.J., May 1955).