Sagebrush Somewhere Near the Tops of the Alluvial Fans Where the Primary Fault Lines of the Mountain Range Are Situated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Distribution of Sagebrush Voles, Lagurus Curtatus, in South-Central Washington Author(S): Thomas P

American Society of Mammalogists Ecological Distribution of Sagebrush Voles, Lagurus curtatus, in South-Central Washington Author(s): Thomas P. O'Farrell Source: Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Aug., 1972), pp. 632-636 Published by: American Society of Mammalogists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1379063 . Accessed: 28/08/2013 16:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Mammalogists is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Mammalogy. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.193.8.24 on Wed, 28 Aug 2013 16:58:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 632 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 53, No. 3 curved needle. After perfusion with penicillin G, the second incision was closed. The base of the plug was slipped into the first incision and sutured to the lumbodorsal fascia with 5-0 Mersilene (Ethicon). After perfusion around the plug with penicillin G, the skin was sutured around the narrow neck of the plug and the incision was dusted with antibiotic powder. The bat could be lifted by the plug with no apparent discomfort and no distortion of the skin or damage to the electrodes. -

Mammals – Columbia

Mammals – Columbia NWR Family Genus Species Common Name Soricidae vagrans Vagrant shrew Sorex (Shrews) merriami Merriam’s shrew Parastrellus hesperus Canyon bat Corynihinus townsendii Townsend’s big-eared bat Eptesicus fuscus Big brown bat Antrozous pallidus Pallid bat Euderma maculatum Spotted bat Lasionycteris noctivagans Silver-haired bat Vespertilionidae (Vesper bats) californicus California myotis ciliolabrum Western small-footed myotis evotis Long-eared myotis Myotis lucifugus Little brown myotis volans Long-legged myotis yumaensis Yuma myotis thysanodes Fringed myotis Lepus californicus Black-tailed jackrabbit Leporidae (Rabbits & hares) Sylvilagus nuttallii Nuttall’s cottontail Marmota flaviventris Yellow-bellied marmot Sciuridae (Squirrels) Urocitellus washingtoni Washington ground squirrel Castoridae (Beavers) Castor canadensis Beaver Geomidae (Pocket gophers) Thomomys talpoides Northern pocket gopher Perognathus parvus Great Basin pocket mouse Heteromyidae (Heteromyids) Dipodomys ordii Ord’s kangaroo rat Reithrodontomys megalotis Western harvest mouse Peromyscus maniculatus Deer mouse Onychomys leucogaster Northern grasshopper mouse Neotoma cinerea Bushy-tailed woodrat Cricetidae (Cricetids) montanus Montane vole Microtus pennsylvanicus Meadow vole Lemmiscus curtatus Sagebrush vole Ondatra zibethica Muskrat Eutamias minimus Least chipmunk Erethizontidae (New World porcupines) Erethizon dorsatum Porcupine Muridae (Old World mice) Rattus norvegicus Norway rat 1 Mammals – Columbia NWR Family Genus Species Common Name Mus musculus House mouse Canidae (Dogs & wolves) Canis latrans Coyote Procyonidae (Raccoons) Procyon lotor Raccoon frenata Long-tailed weasel Mustela vison Mink Mustelidae (Weasels) Lutra canadensis River otter Taxidea taxus Badger Mephitis mephitis Striped skunk Lynx rufus Bobcat Felidae (Cats) Felis concolor Mountain lion hemionus Mule deer Odocoileus Cervidae (Deer) virginianus White-tailed deer Cervus elaphus Rocky Mountain elk 2. -

Estimating the Energy Expenditure of Endotherms at the Species Level

Canadian Journal of Zoology Estimating the energy expenditure of endotherms at the species level Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2020-0035 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 17-Feb-2020 Author: Complete List of Authors: McNab, Brian; University of Florida, Biology Is your manuscript invited for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue?: Draft arvicoline rodents, BMR, Anatidae, energy expenditure, endotherms, Keyword: Meliphagidae, Phyllostomidae © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 42 Canadian Journal of Zoology Estimating the energy expenditure of endotherms at the species level Brian K. McNab B.K. McNab, Department of Biology, University of Florida 32611 Email for correspondence: [email protected] Telephone number: 1-352-392-1178 Fax number: 1-352-392-3704 The author has no conflict of interest Draft © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Zoology Page 2 of 42 McNab, B.K. Estimating the energy expenditure of endotherms at the species level. Abstract The ability to account with precision for the quantitative variation in the basal rate of metabolism (BMR) at the species level is explored in four groups of endotherms, arvicoline rodents, ducks, melaphagid honeyeaters, and phyllostomid bats. An effective analysis requires the inclusion of the factors that distinguish species and their responses to the conditions they encounter in the environment. These factors are implemented by changes in body composition and are responsible for the non-conformity of species to a scaling curve. Two concerns may limit an analysis. The factors correlatedDraft with energy expenditure often correlate with each other, which usually prevents them from being included together in an analysis, thereby preventing a complete analysis, implying the presence of factors other than mass. -

Weiss Et Al, 1995) This Paper Disputes the Interpretation of Castor Et Al

EVALUATION OF THE GEOLOGIC RELATIONS AND SEISMOTECTONIC STABILITY OF THE YUCCA MOUNTAIN AREA NEVADA NUCLEAR WASTE SITE INVESTIGATION (NNWSI) PROGRESS REPORT 30 SEPTEMBER 1995 CENTER FOR NEOTECTONIC STUDIES MACKAY SCHOOL OF MINES UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO DISTRIBUTION OF ?H!S DOCUMENT IS UKLMTED DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document CONTENTS SECTION I. General Task Steven G. Wesnousky SECTION II. Task 1: Quaternary Tectonics John W. Bell Craig M. dePolo SECTION III. Task 3: Mineral Deposits Volcanic Geology Steven I. Weiss Donald C. Noble Lawrence T. Larson SECTION IV. Task 4: Seismology James N. Brune Abdolrasool Anooshehpoor SECTION V. Task 5: Tectonics Richard A. Schweickert Mary M. Lahren SECTION VI. Task 8: Basinal Studies Patricia H. Cashman James H. Trexler, Jr. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsi- bility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Refer- ence herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recom- mendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

Plate 1 117° 116°

U.S. Department of the Interior Prepared in cooperation with the Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5175 U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of Energy Plate 1 117° 116° Monitor Range White River Valley Hot Creek Valley 5,577 (1,700) Warm Springs Railroad Valley 6 5,000 4,593 (1,400) Stone Cabin Valley Quinn Canyon Range Tonopah 5,577 (1,700) Ralston Valley NYE COUNTY 4,921 (1,500) LINCOLN COUNTY Big Smoky Valley 5,249 (1,600) 38° 38° 5,906 (1,800) 5,249 (1,600) Ralston Valley Coal Valley 5,249 (1,600) Kawich Range 4,265 (1,300) 4,921 (1,500) 5,249 (1,600) 6,234 (1,900) 5,577 (1,700) 4,921 (1,500) Railroad Valley South CACTUS FLAT 5,200 | 200 Cactus Range Penoyer Valley Goldfield 5,249 (1,600) 3,800 | 3,800 4,921 (1,500) Clayton Valley 3,609 (1,100) Rachel Sand Spring Valley 5,249 (1,600) 5,577 (1,700) Sarcobatus Flat North Kawich Valley 4,593 (1,400) 5,600 | 5,600 93 Pahranagat Valley 4,921 4,593 (1,400) 4,593 (1,400)5,249 3,937 (1,200)4,265 (1,300) Gold Flat Pahranagat Range 4,921 (1,500) Pahute Mesa–Oasis Valley 6,300 | 5,900 Belted Range Alamo 4,265 (1,300) 4,593 (1,400) 3,609 (1,100) Scottys Emigrant Valley Junction Black Pahute Mesa Nevada National Mountain Security Site 3,281 (1,000) NYE COUNTY Sarcobatus Flat ESMERALDA COUNTY ESMERALDA Rainier Mesa 3,937 (1,200) Yucca Flat Timber Death Valley North Mountain 4,000 | 4,000 Yucca Flat Sarcobatus Flat South Oasis Valley subbasin Grapevine 37° 37° Springs area 1,900 | 1,900 4,265 Grapevine Mountains Bullfrog Hills 2,297 (700) 100 | 100 3,937 (1,200) Ash Meadows 20,50020,500 | -

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

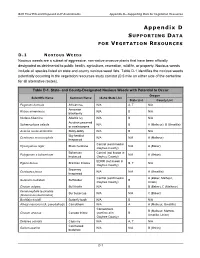

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

Growth Curve of White-Tailed Antelope Squirrels from Idaho

Western Wildlife 6:18–20 • 2019 Submitted: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 3 May 2019. GROWTH CURVE OF WHITE-TAILED ANTELOPE SQUIRRELS FROM IDAHO ROBERTO REFINETTI Department of Psychological Science, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho 83725, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Daytime rodent trapping in the Owyhee Desert of Idaho produced a single diurnal species: the White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammospermophilus leucurus). I found four females that were pregnant and took them back to my laboratory to give birth and I raised their litters in captivity. Litter size ranged from 10 to 12 pups. The pups were born weighing 3–4 g, with purple skin color and with the eyes closed. Pups were successfully weaned at 60 d of age and approached the adult body mass of 124 g at 4 mo of age. Key Words.—Ammospermophilus leucurus; Great Basin Desert; growth; Idaho; Owyhee County The White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammo- not differ significantly (t = 0.715, df = 10, P = 0.503). spermophilus leucurus; Fig. 1) is indigenous to a large After four months in the laboratory (after parturition and segment of western North America, from as far north lactation for the four pregnant females), average body as southern Idaho and Oregon (43° N) to as far south mass stabilized at 124 g (106–145 g). as the tip of the Baja California peninsula (23° N; Belk The four pregnant females were left undisturbed and Smith 1991; Koprowski et al. 2016). I surveyed a in individual polypropylene cages with wire tops (36 small part of the northernmost extension of the range cm length, 24 cm width, 19 cm height). -

MAMMALS of WASHINGTON Order DIDELPHIMORPHIA

MAMMALS OF WASHINGTON If there is no mention of regions, the species occurs throughout the state. Order DIDELPHIMORPHIA (New World opossums) DIDELPHIDAE (New World opossums) Didelphis virginiana, Virginia Opossum. Wooded habitats. Widespread in W lowlands, very local E; introduced from E U.S. Order INSECTIVORA (insectivores) SORICIDAE (shrews) Sorex cinereus, Masked Shrew. Moist forested habitats. Olympic Peninsula, Cascades, and NE corner. Sorex preblei, Preble's Shrew. Conifer forest. Blue Mountains in Garfield Co.; rare. Sorex vagrans, Vagrant Shrew. Marshes, meadows, and moist forest. Sorex monticolus, Montane Shrew. Forests. Cascades to coast, NE corner, and Blue Mountains. Sorex palustris, Water Shrew. Mountain streams and pools. Olympics, Cascades, NE corner, and Blue Mountains. Sorex bendirii, Pacific Water Shrew. Marshes and stream banks. W of Cascades. Sorex trowbridgii, Trowbridge's Shrew. Forests. Cascades to coast. Sorex merriami, Merriam's Shrew. Shrub steppe and grasslands. Columbia basin and foothills of Blue Mountains. Sorex hoyi, Pygmy Shrew. Many habitats. NE corner (known only from S Stevens Co.), rare. TALPIDAE (moles) Neurotrichus gibbsii, Shrew-mole. Moist forests. Cascades to coast. Scapanus townsendii, Townsend's Mole. Meadows. W lowlands. Scapanus orarius, Coast Mole. Most habitats. W lowlands, central E Cascades slopes, and Blue Mountains foothills. Order CHIROPTERA (bats) VESPERTILIONIDAE (vespertilionid bats) Myotis lucifugus, Little Brown Myotis. Roosts in buildings and caves. Myotis yumanensis, Yuma Myotis. All habitats near water, roosting in trees, buildings, and caves. Myotis keenii, Keen's Myotis. Forests, roosting in tree cavities and cliff crevices. Olympic Peninsula. Myotis evotis, Long-eared Myotis. Conifer forests, roosting in tree cavities, caves and buildings; also watercourses in arid regions. -

Figure 3-72. Groundwater Usage in Nevada in 2000. (Source: DIRS 175964-Lopes and Evetts 2004, P

AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT – CALIENTE RAIL ALIGNMENT Figure 3-72. Groundwater usage in Nevada in 2000. (Source: DIRS 175964-Lopes and Evetts 2004, p. 7.) There are a number of published estimates of perennial yield for many of the hydrographic areas in Nevada, and those estimates often differ by large amounts. The perennial-yield values listed in Table 3-35 predominantly come from a single source, the Nevada Division of Water Planning (DIRS 103406-Nevada Division of Water Planning 1992, for Hydrographic Regions 10, 13, and 14); therefore, the table does not show a range of values for each hydrographic area. In the Yucca Mountain area, the Nevada Division of Water Planning identifies a combined perennial yield for hydrographic areas 225 through 230. DOE obtained perennial yields from Data Assessment & Water Rights/Resource Analysis of: Hydrographic Region #14 Death Valley Basin (DIRS 147766-Thiel 1999, pp. 6 to 12) to provide estimates for hydrographic areas the Caliente rail alignment would cross: 227A, 228, and 229. That 1999 document presents perennial-yield estimates from several sources. Table 3-35 lists the lowest (that is, the most conservative) values cited in that document, which is consistent with the approach DOE used in the Yucca Mountain FEIS (DIRS 155970-DOE 2002, p. 3-136). DOE/EIS-0369 3-173 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT – CALIENTE RAIL ALIGNMENT Table 3-35 also summarizes existing annual committed groundwater resources for each hydrographic area along the Caliente rail alignment. However, all committed groundwater resources within a hydrographic area might not be in use at the same time. Table 3-35 also includes information on pending annual duties within each of these hydrographic areas. -

Amargosa Desert Hydrographic Basin 14-230

STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCES JASON KING, P.E. STATE ENGINEER AMARGOSA DESERT HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN 14-230 GROUNDWATER PUMPAGE INVENTORY WATER YEAR 2015 Field Investigated by: Tracy Geter Report Prepared by: Tracy Geter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 1 HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN SUMMARY ................................................................................... 2 PURPOSE AND SCOPE .............................................................................................................. 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA .................................................................................. 3 GROUNDWATER LEVELS ....................................................................................................... 3 METHODS TO ESTIMATE PUMPAGE .................................................................................. 4 PUMPAGE BY MANNER OF USE ........................................................................................... 5 TABLES ......................................................................................................................................... 6 FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... 7 APPENDIX A. AMARGOSA DESERT 2015 GROUNDWATER PUMPAGE BY APPLICATION NUMBER ...........................................................................................