Growth Curve of White-Tailed Antelope Squirrels from Idaho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program & Faculty Guide

Program & Faculty Guide UNLV School of Life Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, LAS VEGAS Contents From the Director ..................... 3 About UNLV .............................. 4 Programs .................................. 5 Facilities ................................... 7 Graduate Students ..................11 Postdoctoral Scholars ............13 Faculty Researchers .............. 15 UNLV School of Life Sciences From the Director The School of Life Sciences (SoLS) is one of the largest academic units on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) campus. It has 30 full-time faculty members, 10 adjunct and research faculty, more than 1,900 undergraduate majors, and approximately 55 graduate students. The school’s offices and laborato- ries are located in four buildings: Juanita Greer White Hall (WHI), the Science and Engineering Building (SEB), the White Hall Annex (WHA2), the Campus Lab Building (CLB). Research facilities on campus include centers for bioinformatics/biostatics with access to supercomputer facilities, confocal and biological imaging core with a new a high-speed laser-scanning microscope, genomics center, greenhouses, tissue culture facilities, environmental chambers and mod- ern animal care facilities. The faculty research and graduate programs are or- ganized into Bioinformatics, Cell & Molecular Biology, Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Integrative Physiology, School of Life Sciences Director Frank van Breukelen and Microbiology. SoLS faculty are recruited from some of the best research institutions and currently collaborate with the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine (NIPM), Lou Ruvo Center, Desert Research Institute (DRI), BLM, USGS, US National Park Service, and with faculty and researchers at many universities and government agencies throughout the nation and international institutions, providing ex- panded opportunities for our students. The faculty compete successfully for funding from BLM, DOE, DOI, FWS, NASA, NIH, NSF, USDA, USGS and other agencies. -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Filed As WSR 17-20-030 on September 27, 2017

CODE REVISER USE ONLY RULE-MAKING ORDER PERMANENT RULE ONLY CR-103P (August 2017) (Implements RCW 34.05.360) Agency: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife: 17-254 Effective date of rule: Permanent Rules ☒ 31 days after filing. ☐ Other (specify) (If less than 31 days after filing, a specific finding under RCW 34.05.380(3) is required and should be stated below) Any other findings required by other provisions of law as precondition to adoption or effectiveness of rule? ☐ Yes ☒ No If Yes, explain: Purpose: The proposal will reclassify loggerhead sea turtle from the state’s threatened subcategory (WAC 220-200-100) to state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). In addition, the proposal will classify the yellow-billed cuckoo under the state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). Citation of rules affected by this order: New: Repealed: Amended: 220-200-100 and 220-610-010. Suspended: Statutory authority for adoption: RCW 77.04.012; 77.04.055; 77.12.020; 77.12.047 Other authority: None. PERMANENT RULE (Including Expedited Rule Making) Adopted under notice filed as WSR 17-13-131 on June 21, 2017 (date). Describe any changes other than editing from proposed to adopted version: WAC 220-200-100 Wildlife classified as protected shall not be hunted or fished. Proposed corrections to common and scientific names include the following: Common Name Scientific Name sage grouse Centrocercus urophasianus sharp-tailed grouse Phasianus columbianus gray whale Eschrichtius gibbosus least chipmunk Tamius minimus yellow-pine chipmunk Tamius amoenus -

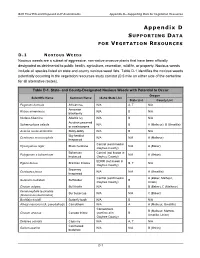

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

Alarm-Calling and Response Behaviors of the Black-Tailed Prairie Dog in Kansas Lloyd W

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Fall 2011 Alarm-Calling And Response Behaviors Of The Black-Tailed Prairie Dog In Kansas Lloyd W. Towers III Fort Hays State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Towers, Lloyd W. III, "Alarm-Calling And Response Behaviors Of The lB ack-Tailed Prairie Dog In Kansas" (2011). Master's Theses. 158. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. ALARM-CALLING AND RESPONSE BEHAVIORS OF THE BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOG IN KANSAS being A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Lloyd Winston Towers III B.S., Texas A&M University Date_____________________ Approved__________________________________ Major Professor Approved__________________________________ Chair, Graduate Council This Thesis for The Master of Science Degree By Lloyd Winston Towers III Has Been Approved __________________________________ Chair, Supervisory Committee __________________________________ Supervisory Committee __________________________________ Supervisory Committee __________________________________ Supervisory Committee __________________________________ Chair, Department of Biological Sciences i This thesis is written in the style appropriate for publication in the Journal of Mammalogy. ii ABSTRACT Prairie dogs ( Cynomys spp.) use alarm calls to warn offspring and other kin of predatory threats. Dialects occur when vocalizations contain consistent differences among populations not isolated by geographic barriers. -

Identification Guide of Invasive Alien Species of Union Concern

Identification guide of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern Support for customs on the identification of IAS of Union concern Project task ENV.D.2/SER/2016/0011 (v1.1) Text: Riccardo Scalera, Johan van Valkenburg, Sandro Bertolino, Elena Tricarico, Katharina Lapin Illustrations: Massimiliano Lipperi, Studio Wildart Date of completion: 6/11/2017 Comments which could support improvement of this document are welcome. Please send your comments by e-mail to [email protected] This technical note has been drafted by a team of experts under the supervision of IUCN within the framework of the contract No 07.0202/2016/739524/SER/ENV.D.2 “Technical and Scientific support in relation to the Implementation of Regulation 1143/2014 on Invasive Alien Species”. The information and views set out in this note do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this note. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents Gunnera tinctoria 2 Alternanthera philoxeroides 8 Procambarus fallax f. virginalis 13 Tamias sibiricus 18 Callosciurus erythraeus 23 Gunnera tinctoria Giant rhubarb, Chilean rhubarb, Chilean gunnera, Nalca, Panque General description: Synonyms Gunnera chilensis Lam., Gunnera scabra Ruiz. & Deep-green herbaceous, deciduous, Pav., Panke tinctoria Molina. clump-forming, perennial plant with thick, wholly rhizomatous stems Species ID producing umbrella-sized, orbicular or Kingdom: Plantae ovate leaves on stout petioles. -

Sciurid Phylogeny and the Paraphyly of Holarctic Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31 (2004) 1015–1030 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Sciurid phylogeny and the paraphyly of Holarctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus) Matthew D. Herron, Todd A. Castoe, and Christopher L. Parkinson* Department of Biology, University of Central Florida, 4000 Central Florida Blvd., Orlando, FL 32816-2368, USA Received 26 May 2003; revised 11 September 2003 Abstract The squirrel family, Sciuridae, is one of the largest and most widely dispersed families of mammals. In spite of the wide dis- tribution and conspicuousness of this group, phylogenetic relationships remain poorly understood. We used DNA sequence data from the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of 114 species in 21 genera to infer phylogenetic relationships among sciurids based on maximum parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic methods. Although we evaluated more complex alternative models of nucleotide substitution to reconstruct Bayesian phylogenies, none provided a better fit to the data than the GTR + G + I model. We used the reconstructed phylogenies to evaluate the current taxonomy of the Sciuridae. At essentially all levels of relationships, we found the phylogeny of squirrels to be in substantial conflict with the current taxonomy. At the highest level, the flying squirrels do not represent a basal divergence, and the current division of Sciuridae into two subfamilies is therefore not phylogenetically informative. At the tribal level, the Neotropical pygmy squirrel, Sciurillus, represents a basal divergence and is not closely related to the other members of the tribe Sciurini. At the genus level, the sciurine genus Sciurus is paraphyletic with respect to the dwarf squirrels (Microsciurus), and the Holarctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus) are paraphyletic with respect to antelope squirrels (Ammosper- mophilus), prairie dogs (Cynomys), and marmots (Marmota). -

Body Size and Diet Mediate Evolution of Jaw Shape in Squirrels (Sciuridae)

Rare ecomorphological convergence on a complex adaptive landscape: body size and diet mediate evolution of jaw shape in squirrels (Sciuridae) *Miriam Leah Zelditch; Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; [email protected] Ji Ye; Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; [email protected] Jonathan S. Mitchell; Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; [email protected] Donald L. Swiderski, Kresge Hearing Research Institute and Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan. [email protected] *Corresponding Author Running head: Convergence on a complex adaptive landscape Key Words: Convergence, diet evolution, jaw morphology, shape evolution, macroevolutionary adaptive landscape, geometric morphometrics Data archival information: doi: 10.5061/dryad.kq1g6. This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/evo.13168. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Abstract Convergence is widely regarded as compelling evidence for adaptation, often being portrayed as evidence that phenotypic outcomes are predictable from ecology, overriding contingencies of history. However, repeated outcomes may be very rare unless adaptive landscapes are simple, structured by strong ecological and functional constraints. One such constraint may be a limitation on body size because performance often scales with size, allowing species to adapt to challenging functions by modifying only size. When size is constrained, species might adapt by changing shape; convergent shapes may therefore be common when size is limiting and functions are challenging. -

IRBP) in Ground Squirrels and Blind Mole Rats

Molecular Evolution of the Interphotoreceptor Retinoid Binding Protein (IRBP) in Ground Squirrels and Blind Mole Rats Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Research Distinction in Biology in the Undergraduate Colleges of The Ohio State University by Bethany N. Army The Ohio State University December 2015 Project Advisor: Dr. Ryan W. Norris, Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology Abstract Blind mole rats are subterranean rodents and spend most of their lifetime underground. Because these mammals live in a dark environment, their eyes have physically changed and even the role played by their eyes has changed. The processing of visual information begins in the retina, with the detection of light by photoreceptor cells. Interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein (IRBP) is a transport protein, which facilitates exchange between photoreceptors and retinal-pigmented epithelium. The IRBP gene has been commonly used in rodent phylogenetic analyses, so I analyzed IRBP in blind mole rats to interpret its evolution and to see if there were any changes among the amino acids in the protein. To do this I used molecular data (cytochrome b and IRBP) from two groups of rodents, the muroids and the marmotines. I constructed phylogenetic trees and interpreted the amino acid sequence of IRBP. Blind mole rats had a slower rate of evolution than expected, but there were changes along the amino acid sequence of IRBP, which may indicate that the IRBP gene is functioning in a specialized way to meet the needs of the particular lifestyle of this mammal. Introduction: Blind mole rats, subfamily Spalacinae, are burrowing mammals that spend most of their life underground. -

University of Nevada, Reno Plant Community Response to Mowing In

University of Nevada, Reno Plant community response to mowing in Wyoming big sagebrush habitat in Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Natural Resources and Environmental Science By Matthew Church Sherman Swanson/Thesis Advisor May 2017 Copyright by Matthew Church 2017 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by MATTHEW CHURCH Entitled Plant Community Response to Mowing in Wyoming Big Sagebrush Habitat in Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Sherman Swanson, Phd, Advisor Elizabeth Leger, Phd, Committee Member Barry Perryman, Phd, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Thousands of acres of Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis) habitat have been mowed throughout Nevada to create fuelbreaks for wildfire control, enhance resilience and resistance to invasive plant species, increase perennial herbaceous understory, and improve wildlife habitat. To improve our understanding of how these plant communities respond to mowing and whether treatment goals are being met, an observational study of paired mowed and unmowed locations was conducted between 2010 and 2015 across the geographic extent of mowed Wyoming big sagebrush in Nevada. In 2015, foliar and ground cover, perennial herbaceous density, and soil profile data were collected at 32 locations within 16 individual mow projects of different ages. Wilcoxon signed rank tests indicated significantly different mean cover values of ground cover, functional groups and individual species between treated and untreated locations. Bare ground (p < 0.01), moss (p < 0.01), cryptogam (p = 0.01), total foliar cover (p < 0.01), non resprouting shrub (p < 0.01), Poa secunda (p = 0.01) and Phlox sp.