Raptors and the Energy Sector Understudied Open Land Raptors Migration I (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Spring/Summer Newsletter

Debbie’s Farewell Party Taking Flight: News From The Ridge 2012 On Saturday April 14th, we wished Debbie (Waters) Petersen all the best on her Board of Directors new journey post-Hawk Ridge. Over 50 were in attendance to celebrate, roast, Spring/Summer Issue | 2012 and say good-bye. Debbie will be teaching secondary life science in Walker, MN Chair: this fall. She has established a great education foundation for Hawk Ridge. We Golden Eagle by Mark MartellRidge Karen Stubenvoll thank her for her 11 years of hard work and dedication. Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in North America are primarily found in the west- Treasurer: ern United States and Canada from Alaska south into north-central Mexico. Historically, small Molly Thompson breeding populations also occurred in eastern North America from Canada south into the U.S. through the Appalachian and Adirondack Mountains, but currently are found only in Canada. There are no breeding records from any upper Mid- Secretary: western state. Jan Green A very large raptor, Golden Eagles have brown plumage which in the adults is complemented by a golden crown and gray bars on the tail. Juveniles have plumage similar to the adults but with whit at the base of the secondaries and inner primaries and a large patch of white on the tail. Golden Eagles are typically birds of hilly or mountainous open coun- Member: try. However in Eastern North America they are found in forested areas that have small openings which the birds use for David Alexander hunting. This eagle feeds mainly on medium sized mammals such as hares, rabbits, squirrels and prairie dogs. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

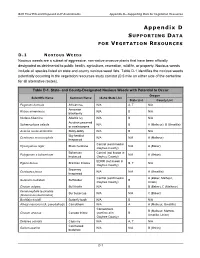

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

Growth Curve of White-Tailed Antelope Squirrels from Idaho

Western Wildlife 6:18–20 • 2019 Submitted: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 3 May 2019. GROWTH CURVE OF WHITE-TAILED ANTELOPE SQUIRRELS FROM IDAHO ROBERTO REFINETTI Department of Psychological Science, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho 83725, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Daytime rodent trapping in the Owyhee Desert of Idaho produced a single diurnal species: the White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammospermophilus leucurus). I found four females that were pregnant and took them back to my laboratory to give birth and I raised their litters in captivity. Litter size ranged from 10 to 12 pups. The pups were born weighing 3–4 g, with purple skin color and with the eyes closed. Pups were successfully weaned at 60 d of age and approached the adult body mass of 124 g at 4 mo of age. Key Words.—Ammospermophilus leucurus; Great Basin Desert; growth; Idaho; Owyhee County The White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammo- not differ significantly (t = 0.715, df = 10, P = 0.503). spermophilus leucurus; Fig. 1) is indigenous to a large After four months in the laboratory (after parturition and segment of western North America, from as far north lactation for the four pregnant females), average body as southern Idaho and Oregon (43° N) to as far south mass stabilized at 124 g (106–145 g). as the tip of the Baja California peninsula (23° N; Belk The four pregnant females were left undisturbed and Smith 1991; Koprowski et al. 2016). I surveyed a in individual polypropylene cages with wire tops (36 small part of the northernmost extension of the range cm length, 24 cm width, 19 cm height). -

April 5–7, 2019

ackinaw MRAPTOR FEST AprilApril 55––7,7, 20192019 www.MackinawRaptorFest.org 1 Welcome to the Mackinaw Raptor Fest Welcome to the fourth annual Mackinaw Raptor Fest, offered by the Mackinac Straits Raptor Watch (MSRW). This boutique event attracts both repeat attendees and newcomers. Timed to offer you a chance to see Red-tailed Hawks, Rough-legged Hawks and Golden Eagles during spring migration, the Fest also lets you share the company of other birders and learn about raptors and water birds from exceptional presenters and interpreters. Through your attendance, volunteering, and generous donations, you have enabled MSRW to celebrate its fifth MACKINAC STRAITS RAPTOR WATCH BOARD anniversary. Since 2014, our bird migration research OF DIRECTORS, L-R: STEVE BAKER, DAVE has expanded to embrace hawks, owls, and waterbirds MAYBERRY, JOSH HAAS, JACKIE PILETTE, during both spring and fall migration. Volunteer or KATHY BRICKER, STEVE WAGNER, ED PIKE contracted raptor naturalists greet people and teach NOT PICTURED: BERT EBBERS, MELISSA them about birds at the Hawk Watch. HANSEN, JOANN LEAL, SUE STEWART Starting in 2016, education increased through launching the Mackinaw Raptor Fest, giving dozens of talks and exhibits around Michigan, and earning What is ? more media and on-line coverage. To promote conservation of needed habitat, MSRW submitted data to key decision-makers about the importance of Mackinac Straits Raptor Watch supports the Straits to waterbirds and other migrants. In late the conservation of habitat for migrating 2018, Executive Director Richard Couse joined MSRW birds of prey and waterbirds in the Straits of to enable even more successes. Mackinac region. -

Golden Gate Brochure

Golden Gate National Park Service National Recreation Area U.S. Department of the Interior Golden Gate California If we in the Congress do not act, the majestic area where sea and bay and land meet in a glorious symphony of nature will be doomed. —US Rep. Phillip Burton,1972 Muir Beach; below left: Alcatraz Native plant nursery Tennessee Valley; above: osprey with prey NPS / MARIN CATHOLIC HS NPS / ALISON TAGGART-BARONE view from Marin Headlands BOTH PHOTOS NPS / KIRKE WRENCH toward city HORSE AND VOLUNTEER —NPS / ALISON TAGGART- BARONE; HEADLANDS—NPS / KIRKE WRENCH Petaluma Tomales 101 37 1 Vallejo For city dwellers, it’s not always easy to experience national human uses. The national recreation area’s role as the Bay Ar- GOLDEN GATE Tomales Bay Novato parks without traveling long distances. A new idea emerged in ea’s backyard continues to evolve in ways its early proponents BY THE NUMBERS Point Reyes SAN PABLO National Seashore Samuel P. Taylor BAY the early 1970s: Why not bring parks to the people? In 1972 never imagined. Renewable energy powers public buildings and 81,000 acres of parklands State Park San 80 Congress added two urban expanses to the National Park System: transportation. People of all abilities use accessible trails and Olema Valley Marin Municipal Rafael 36,000 park volunteers Water District Richmond Golden Gate National Recreation Area in the San Francisco Bay other facilities, engaging in activities that promote health and 1 Rosie the Riveter / Gulf of the Farallones See below WWII Home Front National Marine Sanctuary 29,000 yearly raptor sightings for detail 580 National Historical area and its eastern counterpart Gateway National Recreation wellness. -

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SAN Franciscoa

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF SAN FRANCISCOa View of San Francisco, formerly Yerba Buena, in 1846-7, before the discovery of gold (Library of Congress) Third Edition June 2021 Compiled by Mike Wood, Co-Chairman, Rare Plants Committee California Native Plant Society - Yerba Buena Chapter ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF SAN FRANCISCO FOOTNOTES This Checklist covers the extirpated and extant native and non-native plants reported from natural and naturalistic areas within the City and County of San Francisco. These areas include lands falling under the jurisdiction of the City and County of San Francisco (e.g., the Recreation and Parks Department, the Real Estate Division, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, the a Department of Public Works, and the San Francisco Unified School District); the National Park Service (e.g., the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the Presidio Trust); the California Department of Parks and Recreation; the University of California, San Francisco; the University of San Francisco; and privately owned parcels. References and data sources are listed in APPENDIX 1. b FAMILY: Family codes, family names and all genera mentioned in the Checklist are listed in APPENDIX 3. SCIENTIFIC NAME: Scientific names and taxonomy conform to the Jepson Flora Project (JFP, 2021). Taxa in BOLD TYPE are listed as endangered, threatened or rare (federal / state / CNPS). Nomenclature used in Howell, et al. (1958) is UNDERLINED. c Taxa highlighted in GRAY are indigenous to San Francisco, but which are presumed extirpated (i.e., those which have not been reported here since 1980, other than those that have been reintroduced). -

Pacific Raptor 41

PACIFIC RAPTOR GOLDEN GATE RAPTOR OBSERVATORY ISSUE 41 FALL MIGRATION PUBLISHED AUGUST 2020 2019 Red-tailed Hawk. Photo: Veronica Pedraza Front Cover Artwork: Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus) migrating past Hawk Hill. 12x16 Gouache painting on paper by Bryce W. Robinson. Bryce is an ornithologist and illustrator who works to integrate visual media and research to better communicate topics in ornithology. You can see more of Bryce's work at www.ornithologi.com. 2 FALL MIGRATION 2019 PACIFIC RAPTOR 41 FEATURE CONTENTS 1 Announcements 3 DIRECTOR'S NOTE Raptors in Light of Climate Change HAWKWATCH 7 The Complex Art of "Seeing" Reptors 9 Measuring the Rate of Raptors BANDING 15 Training the Next Generation of Raptor Biologists 19 Changes in Migrating Accipiters BAND RECOVERIES & ENCOUNTERS 25 GGRO Recovery Data Supports Airport Safety 29 Recent Records 41 Turkey Vulture Update: The Story of 368 43 OUTREACH Five Years of Migratory Story 45 Pinnacles National Park: Unexpected Nest-Mates 47 INTERN INTERVIEW Dr. Linnea Hall 51 PEREGRINATIONS Winter Raptors at Lynch Canyon PACIFIC RAPTOR 3 GGRO bander and docent Lynn Schofield releases a Cooper's Hawk at a weekend Hawk Talk program. Photo: Paula Eberle 4 FALL MIGRATION 2019 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Dear Friend of the GGRO, e write this in September 2020, when many uncertainties about the COVID-19 pandemic remain. For more than three decades, the Parks W Conservancy has invited people to the Golden Gate National Parks to support deep and meaningful ecological work through community science. And when the time is right, when we can assure physical distancing and other safety measures, we look forward to continuing to do exactly that once again. -

University of Nevada, Reno Plant Community Response to Mowing In

University of Nevada, Reno Plant community response to mowing in Wyoming big sagebrush habitat in Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Natural Resources and Environmental Science By Matthew Church Sherman Swanson/Thesis Advisor May 2017 Copyright by Matthew Church 2017 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by MATTHEW CHURCH Entitled Plant Community Response to Mowing in Wyoming Big Sagebrush Habitat in Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Sherman Swanson, Phd, Advisor Elizabeth Leger, Phd, Committee Member Barry Perryman, Phd, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Thousands of acres of Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis) habitat have been mowed throughout Nevada to create fuelbreaks for wildfire control, enhance resilience and resistance to invasive plant species, increase perennial herbaceous understory, and improve wildlife habitat. To improve our understanding of how these plant communities respond to mowing and whether treatment goals are being met, an observational study of paired mowed and unmowed locations was conducted between 2010 and 2015 across the geographic extent of mowed Wyoming big sagebrush in Nevada. In 2015, foliar and ground cover, perennial herbaceous density, and soil profile data were collected at 32 locations within 16 individual mow projects of different ages. Wilcoxon signed rank tests indicated significantly different mean cover values of ground cover, functional groups and individual species between treated and untreated locations. Bare ground (p < 0.01), moss (p < 0.01), cryptogam (p = 0.01), total foliar cover (p < 0.01), non resprouting shrub (p < 0.01), Poa secunda (p = 0.01) and Phlox sp. -

Marsing Grad’S Career, Page 10 BLM Could Release Records, Page 2 Prep Basketball, Page 11 Ranchers’ Addresses Could Go Public Huskies Win Own Tournament

Childhood days spark Marsing grad’s career, Page 10 BLM could release records, Page 2 Prep basketball, Page 11 Ranchers’ addresses could go public Huskies win own tournament Established 1865 VOL. 26, NO. 1 75 CENTS HOMEDALE, OWYHEE COUNTY, IDAHO WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 5, 2011 New commissioners take office Monday Two commissioners-elect take the oath of office Monday in Murphy. Kelly Aberasturi for District 2 and Joe Merrick for District 3 will begin their terms after a 10 a.m. ceremony in Courtroom 2 of the Owyhee County Courthouse, 20381 State Hwy. 78. Aberasturi starts a four-year term, succeeding fellow Homedale resident George Hyer. A Grand View resident, Merrick will serve two years in succession of Murphy’s Dick Freund. Also taking the oath of office to begin new Kelly Abersaturi four-year terms are Clerk Charlotte Sherburn, District 2 Treasurer Brenda Richards, Assessor Brett Endicott and Coroner Harvey Grimme. The four are incumbents, with only Sherburn seeing a challenge in last year’s Republican primary from Marsing resident Debbie Titus. After the swearing-in ceremony, the Board of County Commissioners reorganization takes place, including the election of a new board chair. District 1 Commissioner Jerry Hoagland New safety signs in a new year (R-Wilson) has been chairman of the board for Motorists line up as they wait for Homedale High School students to clear the crosswalk on Monday the past two years. afternoon. The crosswalk is one of two spanning East Idaho Avenue for which city crews installed Hoagland is the only BOCC holdover and is Joe Merrick safety signs last month to enhance pedestrian safety around the school. -

Oregon's Owyhee Canyonlands

Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands Protecting Our Desert Heritage A Citizens Guide to the Wild Owyhee Canyonlands Three Fingers Butte, proposed Wilderness in the Lower Owyhee Canyonlands. Photo: © Mark W. Lisk 2 oregon’s owyhee canyonlands: protecting oregon’s desert heritage At 1.9 million acres, the Owyhee Canyonlands represents one of the largest conservation opportunities in the United States. Welcome to Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands—the center of the sagebrush sea and iconic landscape of the arid West. This remote corner of Southeast Oregon calls to those seeking solitude, unconfined space and a self-reliant way of life. Come raft the Wild & Scenic Owyhee River; hunt big game and upland birds; and walk dry streambeds surrounded by geologic formations from another world. We live and visit here because it is truly unique. owyhee canyonlands campaign 3 Greeley Flat–Owyhee Breaks Wilderness Study Area. Photo © Mark W. Lisk The Oregon Owyhee Canyonlands Campaign is working to protect one of the most expansive and dramatic landscapes in the West, featuring rare wildlife, pristine waterways and incredible outdoor recreational opportunities. Stretching from the mountain ranges of the Great Basin to fertile expanses of the Snake River Plain, the Owyhee Desert ecosystem encompasses nearly 9 million acres across three states. Local residents refer to it as ION country, since the Canyonlands lie at the confluence of Idaho, Oregon and Nevada. The name Seventeen Owyhee hearkens back to a time before state lines were drawn, when three Hawaiian trappers were contiguous Wilderness Study killed by local residents. An archaic spelling of their island home (oh-WYE-hee) became the name of this Areas, spanning landscape of deep riverine canyons and sagebrush sea.