RACIALIZED-GENDERED VIOLENCE in the CRIMINAL PUNISHMENT SYSTEM Eunbyul Lee Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRENGTHENING PARENT and CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 Years)

STRENGTHENING PARENT AND CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 years) A Blue Dot indicates agencies that are a member of the Maternal Mental Health Collaborative and/or have attended the Postpartum Support International training. Being a parent can be very rewarding, but it can also be very challenging. Because your child is always growing, the information you need to know about parenting and child development changes constantly, too. Learning what behaviors are appropriate for your child’s age and how to handle them can help you better respond to your child. “WHERE CAN I LEARN MORE ABOUT MY CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT?” If you are concerned about your child’s development or need more help, contact your child’s pediatrician, teacher, or school counselor. EMPOWERINGPARENTS.COM Articles from the experts at Empowering Parents to help you manage your teen’s behavior more effectively. Is your adolescent breaking curfew, behaving defiantly or engaging in risky behavior? We offer concrete help for teen behavior problems. www.empoweringparents.com AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Adolescence can be a rough time for parents. At times, your teen may be a source of frustration and exasperation, not to mention financial stress. But these years also bring many, many moments of joy, pride, laughter and closeness. Find information about privacy, stress, mental health, and other health-related topics. www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/teen INFOABOUTKIDS.ORG This website has links to well-established, trustworthy websites with common parenting concerns related to your child’s body, mind, emotions, and relationships. infoaboutkids.org AHA! PARENTING Provides lots of great, useful advice on how to handle parenting challenges at all ages. -

The Reconstruction of Gender and Sexuality in a Drag Show*

DUCT TAPE, EYELINER, AND HIGH HEELS: THE RECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN A DRAG SHOW* Rebecca Hanson University of Montevallo Montevallo, Alabama Abstract. “Gender blending” is found on every continent; the Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil exemplify so-called “third genders.” The American version of a third gender may be drag queen performers, who confound, confuse, and directly challenge commonly held notions about the stability and concrete nature of both gender and sexuality. Drag queens suggest that specific gender performances are illusions that require time and effort to produce. While it is easy to dismiss drag shows as farcical entertainment, what is conveyed through comedic expression is often political, may be used as social critique, and can be indicative of social values. Drag shows present a protest against commonly held beliefs about the natural, binary nature of gender and sexuality systems, and they challenge compulsive heterosexuality. This paper presents the results of my observational study of drag queens. In it, I describe a “routine” drag show performance and some of the interactions and scripts that occur between the performers and audience members. I propose that drag performers make dichotomous American conceptions of sexuality and gender problematical, and they redefine homosexuality and transgenderism for at least some audience members. * I would like to thank Dr. Stephen Parker for all of his support during the writing of this paper. Without his advice and mentoring I could never have started or finished this research. “Gender blending” is found on every continent. The Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil are just a few examples of peoples and practices that have been the subjects for “third gender” studies. -

Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women on Femicide Related Data and Information

Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women on femicide related data and information November 2020 The Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Slovenia (National Human Rights Institution) submits the following information to the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, its Causes and Consequences, Ms Dubravka in response to her call for femicide related data and information.1 Administrative data (by numbers and percentage) on homicide/femicide or gender-related killings of women for the last 3 years (2018-2020). The Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Slovenia acquired the following data on the number of homicides/femicides in Slovenia from the Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Slovenia on 18th and 24th November 2020. 1. The total number of homicides of women and men As a homicide/femicide, we considered the following crimes under the Slovenian Criminal Code:2 manslaughter (Article 115),3 murder (Article 116),4 voluntary manslaughter (Article 117)5 and negligent homicide (Article 118).6 In 2018, the police dealt with 49 crimes of homicide. In 21 cases victims were women, in 28 victims were men. In 2019, the police dealt with 27 homicides; women were victims in 8 cases, men were victims in 19. From 1st January to 11th November 2020, the police dealt with 41 homicides, 18 committed against women, 23 against men. 1 Femicide Watch call 2020, www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Women/SRWomen/Pages/FemicideWatchCall2020.aspx 2 Kazenski zakonik (KZ-1), www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO5050. -

FORALL12-13 Proof Read

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331998586 FOR ALL: The Sustainable Development Goals and LGBTI People Research · February 2019 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.23989.73447 CITATIONS READS 0 139 2 authors: Andrew Park Lucas Ramón Mendos University of California, Los Angeles University of California, Los Angeles 17 PUBLICATIONS 6 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Gender Identity and Expression View project LGBTI and international development View project All content following this page was uploaded by Andrew Park on 26 March 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. FOR ALL The Sustainable Development Goals and LGBTI People “We pledge that no one will be left behind…. [T]he Goals and targets must be met for all nations and peoples and for all segments of society.” United Nations General Assembly. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. PREFACE This report was produced pursuant to a consultation contract (2018-05 RAP/SDGs) issued by RFSL Forbundeẗ (Org nr: 802011-9353). This report was authored by Andrew Park and Lucas Ramon Mendos. The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and may not necessarily reflect those of RFSL. Micah Grzywnowicz, RFSL International Advocacy Advisor, contributed to the shaping, editing, and final review of this report. Winston Luhur, Research Assistant, Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, contributed to research which has been integrated into this publication. Ilan Meyer, Ph.D., Williams Distinguished Senior Scholar for Public Policy, Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, Elizabeth Saewyc, Director and Professor at the University of British Columbia School of Nursing, and Carmen Logie, Assistant Professor at Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, provided expert guidance to the authors. -

Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape A Dissertation Presented by Jane Clare Jones to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University December 2016 Copyright by Jane Clare Jones 2016 ii Stony Brook University The Graduate School Jane Clare Jones We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dissertation Advisor – Dr. Edward S Casey Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy Chairperson of Defense – Dr. Megan Craig Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy Internal Reader – Dr. Eva Kittay Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy External Reader – Dr. Fiona Vera-Gray Durham Law School, Durham University, UK This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of the Dissertation Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape by Jane Clare Jones Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University 2016 As Rebecca Whisnant has noted, notions of “national…and…bodily (especially sexual) sovereignty are routinely merged in -

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

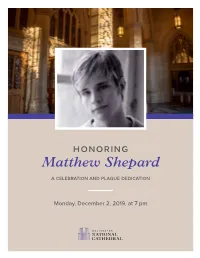

Matthew Shepard

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

Inconsistent Legal Treatment of Unwanted Sexual Advances: a Study of the Homosexual Advance Defense, Street Harassment, and Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Inconsistent Legal Treatment of Unwanted Sexual Advances: A Study of the Homosexual Advance Defense, Street Harassment, and Sexual Harassment in the Workplace Kavita B. Ramakrishnant ABSTRACT In this Article, I contend that unwanted sexual advances on men are treated differently under the law than are unwanted sexual advances on women. I com- pare the legal conceptualization and redress of two of the most common types of unwanted sexual advances faced by women-street harassment and sexual ha- rassment in the workplace-with the legal treatment of unwanted sexual ad- vances on men as seen through the homosexual advance defense. I argue that the law recognizes certain advances on men as inappropriate enough to deserve legal recognition in the form of mitigation of murder charges while factually indistin- guishable advances on women are not even considered severe enough to rise to the level of a legally cognizable claim. Unwanted sexual advances on men do not receive the same level of scruti- ny as unwanted sexual advances on women. First, unwanted advances on men are often conclusively presumed to be unwanted and worthy of legal recognition, whereas unwanted advances on women are more rigorously subjected to a host of procedural and doctrinal barriers. Further, while one nonviolent same-sex ad- vance on a man may be sufficient to demonstrate provocation, there is currently no legal remedy that adequately addresses a nonviolent same-sex advance on a woman. Thus, a woman may not receive legal recognition for experiencing the t J.D., UCLA School of Law, 2009. B.A. University of Pennsylvania, 2004. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law

Nebraska Law Review Volume 76 | Issue 3 Article 2 1997 Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation John Rockwell Snowden, Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup, 76 Neb. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol76/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. John Rockwell Snowden* Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 400 II. A Brief History of Murder and Malice ................. 401 A. Malice Emerges as a General Criminal Intent or Bad Attitude ...................................... 403 B. Malice Becomes Premeditation or Prior Planning... 404 C. Malice Matures as Particular States of Intention... 407 III. A History of Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska ............................................. 410 A. The Statutes ...................................... 410 B. The Cases ......................................... 418 IV. Puzzles of Nebraska Homicide Jurisprudence .......... 423 A. The Problem of State v. Dean: What is the Mens Rea for Second Degree Murder? ... 423 B. The Problem of State v. Jones: May an Intentional Homicide Be Manslaughter? ....................... 429 C. The Problem of State v. Cave: Must the State Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that the Accused Did Not Act from an Adequate Provocation? . -

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel Huber David Jaramillo Gil The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3862 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEER BAROQUE: SARDUY, PERLONGHER, LEMEBEL by HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL All Rights Reserved ii Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Carlos Riobó Chair of Examining Committee Date Carlos Riobó Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paul Julian Smith Magdalena Perkowska THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil Advisor: Carlos Riobó Abstract: This dissertation analyzes the ways in which queer and trans people have been understood through verbal and visual baroque forms of representation in the social and cultural imaginary of Latin America, despite the various structural forces that have attempted to make them invisible and exclude them from the national narrative.