Combating Hate Crimes: Promoting a Re- Sponsive and Responsible Role for the Federal Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

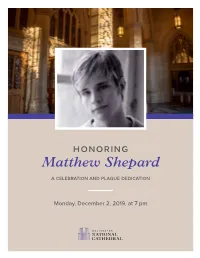

Matthew Shepard

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

1St Activists Conference Lobby

The complete listing of all subversive actions against gender oppression around the US, along with occasional instructions on how to roll your own. Issue 4, Spring 1997 MISSION: Cover all actions related to overthrowing gender oppression, transphobia, genderphobia, homophobia and related oppressive political structures. PUBLISHERS:: EDITORS: Riki Anne Wilchins, Nancy Nangeroni, and Claire Howell. You can reach us at: IYF, c/o, 274 W.11 St. #4R., NYC 10014, or E-Male: [email protected], [email protected] (that’s Nancy). Layout by Nancy. Please do NOT add the IYF address to your mailing list. We're DELUGED with local newsletters and stuff. Please use our address only for press releases (or subscriptions). COST: Included courtesy of your favorite magazine as a free insert. Also published on the Web at http://www.cdspub.com . Subscriptions: $10/year . PUBLISHED: Twice annually, through funding by GenderPAC, "gender, affectional and racial equality." GID has historically been used as a diagnosis for transexuals seeking ! FORTE KILLER PLEADS GUILTY, GETS LIFE hormones for sex-change surgery. However of late, fewer and fewer [Lawrence, MA: Sep 16, 1996] Michael Thompson was sentenced to insurance carriers or HMO¹s have been covering trans-related medical life in prison after pleading guilty to the murder of Debbie Forte. care, and many now explicitly exclude it. Simultaneously, an increasingly Thompson confessed that he had taken Ms. Forte home on May 15, militant combination of gender and queers activists is demanding that 1995, began "Messing around" with her and, upon discovering she had the APA reform GID, claiming it diagnoses them as mentally ill simply a penis, killed her. -

Matthew Shepard Papers

Matthew Shepard Papers NMAH.AC.1463 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Content Description.......................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Shepard, Matthew, Personal Papers, 1976-2019, undated...................... 5 Series 2: Shepard Family and The Matthew Shepard Foundation, Papers and Correspondence Received, 1998-2013, undated................................................... 12 Series 3: Tribute, Vigil, and Memorial Services, Memorabilia, and Inspired Works, 1998-2008, undated.............................................................................................. -

Safe Zone Manual Antioch University/Seattle 2015-2016

AUS Safe Zone Manual 1 FULLY CITED VERSION Safe Zone Manual Antioch University/Seattle 2015-2016 Resources and information guide for people who serve as allies to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning intersex, asexual (LGBTQIA) community The information contained in this manual is based and adapted from Safe Zone and Safe Space programs at other colleges and universities throughout the country. dpw 2.3.16 AUS Safe Zone Manual 2 Table of Contents Program Introduction……………………………………………………………. Purpose Mission statement Goals Who can participate in the program? What do you need to participate as a SAFE ZONE Ally at Antioch/Seattle? Responsibilities for becoming a SAFE ZONE ally Getting Oriented/Terms and Definitions…………………………………………... Terms Related to Sexual Orientation Terms related to Gender, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression What is Homophobia?………………………………………………………… Homophobia How homophobia hurts everyone Homophobic levels of attitude Positive levels of attitude What is Bisexuality? ………………………………………………… Bisexuality Common Myths Dispelled Straight But Not Narrow …………………………………………………………… How to Be an Ally to LGB Coming Out……………………………………………………………………… Coming out What might lesbian, gay men and bisexual people be afraid of? Why might lesbian, gay men and bisexual people want to come out to others? How might lesbian, gay men and bisexual people feel about coming out to someone? How might an individual feel after someone has come out to them? What do lesbian, gay men and bisexual people want from the people they come out to? What are some situations in which someone might come out to you? Ways that you can help when someone comes out to you What Is Heterosexual Privilege?…………………………………….,………….. Heterosexual privilege Advantages of heterosexual privilege Examples of heterosexism Trans/Transgender Issues…………………………………………………. -

Safe Zone Program Participants 2009-2010

A Guide for Brown University Safe Zone Program Participants 2009-2010 Resources and information for people who serve as allies to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning community. The Brown University Safe Zone program is run out of the Brown University LGBTQ Resource Center. Table of Contents: Safe Zone Program Introduction ………………………………………….……………………..... 3 About This Manual ……………………………………………………………………………..… 4 Becoming an Ally: Benefits & Risks ……………………………….……………………………. 4 Sexual Orientation ………………………………………………..…………………………….. 6 Glossary of Terms: Sexual Orientation……………………….……………………… 7 What is Bisexuality? ……………………………………..…..……………………….. 9 ―Coming Out‖ Issues .………….……………………………..…………..……………. 11 What Is Heterosexual Privilege? ……………………………………………………..... 13 How Homophobia Hurts Everyone ……………………………..…………………..… 15 ―Straight But Not Narrow‖: How to be an Ally to Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual People … 16 Gender Identity …………………………………………………………………..……………. 17 Glossary of Terms: TGI……………………………………………………………….. 17 Trans/Transgender Issues……………………………………………………………… 21 Intersex Issues………………………..…………………………………………………. 23 Androgyne, Genderqueer, Bi-Gender, & Multigender Issues ….……………..……….. 24 Working with Trans People: Some Things to Keep In Mind……………….…………. 25 How to be an Ally to Trans People………………………………….………….………. 26 ―What Should I Do If…?‖ Commonly Asked Ally Questions……….……………….…………. 27 Online Resources………………..…………………………………………………….…………. 31 Reporting Gender & Sexuality-Related Bias Incidents…………………………………………. 32 The Brown Safe Zone is -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

The Gift of Anger: Use Passion to Build Not Destroy

If you enjoy this excerpt… consider becoming a member of the reader community on our website! Click here for sign-up form. Members automatically get 10% off print, 30% off digital books. The Gift of Anger The Gift of Anger Use Passion to Build Not Destroy • Joe Solmonese • The Gift of Anger Copyright © 2016 by Joe Solmonese All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distrib- uted, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior writ- ten permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. 1333 Broadway, Suite 1000 Oakland, CA 94612-1921 Tel: (510) 817-2277, Fax: (510) 817-2278 www.bkconnection.com Ordering information for print editions Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by cor- porations, associations, and others. For details, contact the “Special Sales Department” at the Berrett-Koehler address above. Individual sales. Berrett-Koehler publications are available through most bookstores. They can also be ordered directly from Berrett-Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626; www.bkconnection.com Orders for college textbook/course adoption use. Please contact Berrett- Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626. Orders by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesalers. Please contact Ingram Publisher Services, Tel: (800) 509-4887; Fax: (800) 838-1149; E-mail: customer .service@ingram publisher services .com; or visit www .ingram publisher services .com/ Ordering for details about electronic ordering. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 155, Pt

April 29, 2009 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 155, Pt. 8 11081 Thompson (MS) Vela´ zquez Wexler (1) IN GENERAL.—At the request of a State, SEC. 4. GRANT PROGRAM. Thompson (PA) Visclosky Whitfield local, or tribal law enforcement agency, the At- (a) AUTHORITY TO AWARD GRANTS.—The Of- Thornberry Walden Wilson (OH) torney General may provide technical, forensic, fice of Justice Programs of the Department of Tiahrt Walz Wilson (SC) Justice may award grants, in accordance with Tiberi Wamp prosecutorial, or any other form of assistance in Wittman the criminal investigation or prosecution of any such regulations as the Attorney General may Tierney Wasserman Wolf crime that— prescribe, to State, local, or tribal programs de- Titus Schultz Woolsey (A) constitutes a crime of violence; Tonko Waters Wu signed to combat hate crimes committed by juve- Towns Watson (B) constitutes a felony under the State, local, Yarmuth niles, including programs to train local law en- Tsongas Watt Young (AK) or tribal laws; and forcement officers in identifying, investigating, Turner Waxman Young (FL) (C) is motivated by prejudice based on the ac- prosecuting, and preventing hate crimes. Upton Weiner tual or perceived race, color, religion, national (b) AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS.— Van Hollen Welch origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender iden- There are authorized to be appropriated such NOES—19 tity, or disability of the victim, or is a violation sums as may be necessary to carry out this sec- Blunt Flake Royce of the State, local, or tribal hate crime laws. tion. Broun (GA) Gohmert Scalise (2) PRIORITY.—In providing assistance under SEC. -

The Laramie Project – Teacher's Notes

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Company B Belvoir 2. Cast and Production Team 3. About Moisés Kaufman and the Tectonic Theater Project 4. About The Laramie Project a) Into the West: An Exploration of Form b) NYTheater.Com Review c) The Laramie Project (Review) d) Project Scrapped 5. About Laramie 6. About the Issues a) Why One Murder Makes Page One … b) Laramie Project Full-length movie c) The Reluctant Activist d) A Chaplain’s Reflection 7. Internet Links 8. Further Reading Note: These notes are designed to provide a context for viewing a performance of The Laramie Project . The articles and questions and activities are designed to give an insight into the play’s beginnings; the play’s context within the Matthew Shepard murder; and the play as a theatrical work. Rather than being an analysis of the text, these notes are aimed at providing information which will lead to an exploration of the issues, process and ideas which form The Laramie Project . 1 1. Company B Belvoir The originality and energy of Company B Belvoir productions arose out of the unique action taken to save the Nimrod Theater building from demolition in 1984. Rather than lose a performance space in inner city Sydney, more than 600 arts, entertainment and media professionals formed a syndicate to buy the building. The syndicate included nearly every successful person in Australian show business. Company B is one of Australia’s most prestigious theater companies. Under the artistic leadership of Neil Armfield, the company performs in major arts centers and festivals both nationally and internationally and from its home, Belvoir St Theater in Surry Hills, Sydney. -

Guide to the Human Rights Campaign Records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712

Guide to the Human Rights Campaign Records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections Cornell University Library Contact Information: Compiled Date EAD Date Division of Rare and by: completed: encoding: modified: Manuscript Collections Brenda February 2007 Peter Martinez Jude Corina, 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Marston, Rima and Evan Fay June 2015 Cornell University Turner Earle, February Ithaca, NY 14853 2007 (607) 255-3530 Sarah Keen, Fax: (607) 255-9524 January 2008 [email protected] Sarah Keen, June http://rmc.library.cornell.edu 2009 Christine Bonilha, October 2010- April 2011 Bailey Dineen, February 2014 © 2007 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Title: Human Rights Campaign records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712 Creator: Human Rights Campaign (U.S.). Quantity: 109.4 cubic feet Forms of Material: Correspondence, Financial Records, Photographs, Printed Materials, Publications Repository: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library Abstract: Project files, correspondence, financial and administrative records, subject files, press clippings, photographs, and miscellany that, taken together, provide a broad overview of the American movement for lesbian, gay, transgender, and bisexual rights starting in 1980. HRC(F)'s lobbying, voter mobilization efforts, and grassroots organizing throughout the United States are well documented, as are its education and outreach efforts and the work of its various units that have -

Considering Matthew Shepard Craig Hella Johnson

Considering Matthew Shepard Craig Hella Johnson Libretto Commissioned by Fran and Larry Collmann and Conspirare Dedicated to Philip Overbaugh 1 PROLOGUE Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass Ordinary Boy We Tell Each Other Stories PASSION The Fence (before) The Fence (that night) A Protestor Keep It Away From Me (The Wound of Love) Fire of the Ancient Heart We Are All Sons I Am Like You The Innocence The Fence (one week later) Stars In Need of Breath Gently Rest Deer Song (Mist on the Mountains) The Fence (after)/The Wind Pilgrimage EPILOGUE Meet Me Here Thanks All of Us Reprise: This Chant of Life (Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass) 2 PROLOGUE All. Yoodle—ooh, yoodle-ooh-hoo, so sings a lone cowboy, Who with the wild roses wants you to be free. Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass Cattle, horses, sky and grass These are the things that sway and pass Before our eyes and through our dreams Through shiny, sparkly, golden gleams Within our psyche that find and know The value of this special glow That only gleams for those who bleed Their soul and heart and utter need Into the mighty, throbbing Earth From which springs life and death and birth. I’m alive! I'm alive, I'm alive, golden. I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive . These cattle, horses, grass, and sky Dance and dance and never die They circle through the realms of air And ground and empty spaces where A human being can join the song Can circle, too, and not go wrong Amidst the natural, pulsing forces Of sky and grass and cows and horses.