Revenge, Forgiveness and the Responsibility Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

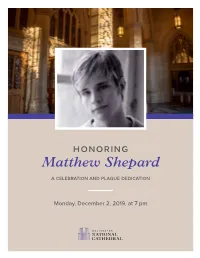

Matthew Shepard

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

Combating Hate Crimes: Promoting a Re- Sponsive and Responsible Role for the Federal Government

S. HRG. 106±517 COMBATING HATE CRIMES: PROMOTING A RE- SPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING HOW TO PROMOTE A RESPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ON COMBATING HATE CRIMES, FOCUSING ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE STATES IN COMBATING HATE CRIME, ANALY- SIS OF STATES' PROSECUTION OF HATE CRIMES, DEVELOPMENT OF A HATE CRIME LEGISLATION MODEL, AND EXISTING FEDERAL HATE CRIME LAW MAY 11, 1999 Serial No. J±106±25 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 64±861 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MANUS COONEY, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hatch, Hon. -

Matthew Shepard Papers

Matthew Shepard Papers NMAH.AC.1463 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Content Description.......................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Shepard, Matthew, Personal Papers, 1976-2019, undated...................... 5 Series 2: Shepard Family and The Matthew Shepard Foundation, Papers and Correspondence Received, 1998-2013, undated................................................... 12 Series 3: Tribute, Vigil, and Memorial Services, Memorabilia, and Inspired Works, 1998-2008, undated.............................................................................................. -

The Gift of Anger: Use Passion to Build Not Destroy

If you enjoy this excerpt… consider becoming a member of the reader community on our website! Click here for sign-up form. Members automatically get 10% off print, 30% off digital books. The Gift of Anger The Gift of Anger Use Passion to Build Not Destroy • Joe Solmonese • The Gift of Anger Copyright © 2016 by Joe Solmonese All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distrib- uted, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior writ- ten permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. 1333 Broadway, Suite 1000 Oakland, CA 94612-1921 Tel: (510) 817-2277, Fax: (510) 817-2278 www.bkconnection.com Ordering information for print editions Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by cor- porations, associations, and others. For details, contact the “Special Sales Department” at the Berrett-Koehler address above. Individual sales. Berrett-Koehler publications are available through most bookstores. They can also be ordered directly from Berrett-Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626; www.bkconnection.com Orders for college textbook/course adoption use. Please contact Berrett- Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626. Orders by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesalers. Please contact Ingram Publisher Services, Tel: (800) 509-4887; Fax: (800) 838-1149; E-mail: customer .service@ingram publisher services .com; or visit www .ingram publisher services .com/ Ordering for details about electronic ordering. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 155, Pt

April 29, 2009 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 155, Pt. 8 11081 Thompson (MS) Vela´ zquez Wexler (1) IN GENERAL.—At the request of a State, SEC. 4. GRANT PROGRAM. Thompson (PA) Visclosky Whitfield local, or tribal law enforcement agency, the At- (a) AUTHORITY TO AWARD GRANTS.—The Of- Thornberry Walden Wilson (OH) torney General may provide technical, forensic, fice of Justice Programs of the Department of Tiahrt Walz Wilson (SC) Justice may award grants, in accordance with Tiberi Wamp prosecutorial, or any other form of assistance in Wittman the criminal investigation or prosecution of any such regulations as the Attorney General may Tierney Wasserman Wolf crime that— prescribe, to State, local, or tribal programs de- Titus Schultz Woolsey (A) constitutes a crime of violence; Tonko Waters Wu signed to combat hate crimes committed by juve- Towns Watson (B) constitutes a felony under the State, local, Yarmuth niles, including programs to train local law en- Tsongas Watt Young (AK) or tribal laws; and forcement officers in identifying, investigating, Turner Waxman Young (FL) (C) is motivated by prejudice based on the ac- prosecuting, and preventing hate crimes. Upton Weiner tual or perceived race, color, religion, national (b) AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS.— Van Hollen Welch origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender iden- There are authorized to be appropriated such NOES—19 tity, or disability of the victim, or is a violation sums as may be necessary to carry out this sec- Blunt Flake Royce of the State, local, or tribal hate crime laws. tion. Broun (GA) Gohmert Scalise (2) PRIORITY.—In providing assistance under SEC. -

The Laramie Project – Teacher's Notes

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Company B Belvoir 2. Cast and Production Team 3. About Moisés Kaufman and the Tectonic Theater Project 4. About The Laramie Project a) Into the West: An Exploration of Form b) NYTheater.Com Review c) The Laramie Project (Review) d) Project Scrapped 5. About Laramie 6. About the Issues a) Why One Murder Makes Page One … b) Laramie Project Full-length movie c) The Reluctant Activist d) A Chaplain’s Reflection 7. Internet Links 8. Further Reading Note: These notes are designed to provide a context for viewing a performance of The Laramie Project . The articles and questions and activities are designed to give an insight into the play’s beginnings; the play’s context within the Matthew Shepard murder; and the play as a theatrical work. Rather than being an analysis of the text, these notes are aimed at providing information which will lead to an exploration of the issues, process and ideas which form The Laramie Project . 1 1. Company B Belvoir The originality and energy of Company B Belvoir productions arose out of the unique action taken to save the Nimrod Theater building from demolition in 1984. Rather than lose a performance space in inner city Sydney, more than 600 arts, entertainment and media professionals formed a syndicate to buy the building. The syndicate included nearly every successful person in Australian show business. Company B is one of Australia’s most prestigious theater companies. Under the artistic leadership of Neil Armfield, the company performs in major arts centers and festivals both nationally and internationally and from its home, Belvoir St Theater in Surry Hills, Sydney. -

Considering Matthew Shepard Craig Hella Johnson

Considering Matthew Shepard Craig Hella Johnson Libretto Commissioned by Fran and Larry Collmann and Conspirare Dedicated to Philip Overbaugh 1 PROLOGUE Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass Ordinary Boy We Tell Each Other Stories PASSION The Fence (before) The Fence (that night) A Protestor Keep It Away From Me (The Wound of Love) Fire of the Ancient Heart We Are All Sons I Am Like You The Innocence The Fence (one week later) Stars In Need of Breath Gently Rest Deer Song (Mist on the Mountains) The Fence (after)/The Wind Pilgrimage EPILOGUE Meet Me Here Thanks All of Us Reprise: This Chant of Life (Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass) 2 PROLOGUE All. Yoodle—ooh, yoodle-ooh-hoo, so sings a lone cowboy, Who with the wild roses wants you to be free. Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass Cattle, horses, sky and grass These are the things that sway and pass Before our eyes and through our dreams Through shiny, sparkly, golden gleams Within our psyche that find and know The value of this special glow That only gleams for those who bleed Their soul and heart and utter need Into the mighty, throbbing Earth From which springs life and death and birth. I’m alive! I'm alive, I'm alive, golden. I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive . These cattle, horses, grass, and sky Dance and dance and never die They circle through the realms of air And ground and empty spaces where A human being can join the song Can circle, too, and not go wrong Amidst the natural, pulsing forces Of sky and grass and cows and horses. -

Download the Conference Program Here

WELCOME Welcome to the Inaugural Indiana Response to Hate Conference! In March 2017, the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana (FHCCI) launched a new project, the Central Indiana Alliance Against Hate. The Alliance was formed thanks to a “Communities Against Hate” rapid-response grant awarded to the FHCCI from the Open Society Foundations. Despite its new start, at this writing, the Alliance is already over 50 organizations strong, coming together to take a stand against hate. With increasing incidents of hate-based crimes and incidents, we felt it was important to bring people together committed to combating and addressing hate through this first-of-its-kind training opportunity. We hope you will be pleased with the speaker line-up, a combination of local and national leaders, committed to finding ways to promote dialogue and discussion on these difficult topics. We are so excited at their willingness to share their knowledge and guidance with us. Thank you for time and your willingness to listen and learn. “No Hate, Just Love.” Amy Nelson, Executive Director Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana 2 Central Indiana Alliance Against Hate & Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE Note: A detailed schedule begins on Page 8. 12:30-12:40 PM: Amy Nelson, Fair Housing 8:00 AM: Registration & Continental Breakfast Center of Central Indiana Open (Blue star on map below) - Central Indiana Alliance Against Hate 9:00-9:05 AM: Welcome (Yellow area on map - Performance by Preacher C below), Amy Nelson, Fair Housing Center of 12:40-12:45 -

The International Court System

1 International www.impoourtorg court System INTERNATIONAL IMPERIAL COURT COUNCIL OF CANADA, UNITED STATES AND MEXICO MEETING MINUTES SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2019 SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Presiding: President of the ICC, Emperor Rob Surreal Executive Board: Executive Director/Chair Nicole Murray Ramirez President Robert Lack 1st Vice President Nicole Diamond 2"d Vice President John Carrillo Recording Secretary Misty Blue Corresponding Secretary Destiny Childs Treasurer Freeda Bangkok Scholarship Chair Terry Sidie Call to Order: 9:03am Roll Call: 2 ICC Member City Present Excused Anni Coque I' ll Doo Alameda, CA Barbie LaChoy Ft. Lauderdale, FL "-.J Bill Mitchell Phoenix, AZ -.J Bobby Childers Salk Lake City, UT -.J Bunnie Cruse Albuquerque, NM -.J Carmine Emilio Caruso Boise, ID -.J Charles Rozanski Denver, CO -.J Cookie Von Shigglesworth Washington, DC -.J Danielle Logan Hawaii -.J Darnel le of Wakanda San Diego, CA -.J Destiny B. Childs Washington, DC -.J Doug Snow Fox Tacoma, WA -.J Dustin D. Cobwebs B. Childs Hartford, CT -.J Freeda Bangkok Cincinnati, OH -.J Fred Worsham Lexington, KY -.J Harrington New York, NY -.J Helen Twelvetrees Las Vegas, NV -.J Hope Jewel Halston Reno, NV -.J Jason Dickson Vanderbilt Toronto -.J Jaylene Tyme Vancouver BC Jerry Coletti Munro San Francisco, CA "-.J John Carrillo San Francisco, CA -.J Just Jack New York, NY -.J Kaleo Tevaitea Ramos Hawaii -.J Karina Samala Los Angeles, CA -.J Landa Lakes San Francisco, CA -.J Logan Storm Providence, RI -.J Mark Allen Surreal Spokane, WA -.J Misha Rockafeller Sacramento, CA/Portland, OR -.J Misty Blue San Francisco, CA -.J Nathan Page San Francisco, CA -.J Nicole Diamond Lexington, KY -.J Peter Storm Bellingham, WA -.J Petty Cash Cincinnati, OH -.J Reba MacEnwhat Boise, ID -.J Robert Buckner Ft. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MAY 3, 2007 No. 72 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. WELCOMING THE REVEREND RICK Mr. KUCINICH. Madam Speaker, to- The Reverend Rick Astle, Director of ASTLE day’s news indicates the Iraqis are be- Missions, Waccamaw Baptist Associa- ginning to be upset that the Bush ad- (Mr. MCINTYRE asked and was given tion, Conway, South Carolina, offered ministration, with the unfortunate permission to address the House for 1 the following prayer: help of this Congress, is trying to force minute.) Our Father in heaven, on this Na- the sovereign Government of Iraq to Mr. MCINTYRE. Madam Speaker, I tional Day of Prayer, we confess that am pleased to introduce the Reverend pass a hydrocarbon act which will give Your way is perfect, Your Word is prov- Rick Astle, who just delivered the in- the U.S. oil companies control of $6 en, and You are a shield to all who vocation for the U.S. House as we begin trillion worth of Iraqi oil assets. trust in You. this National Day of Prayer, a time Now, the wealth of Iraq, the oil wells, Make today a day when men are will- when communities across America will ought to be decided by an Iraq Govern- ing to repent of sin and to look to You be joining in prayer for our country ment not under U.S. -

Matthew Shepard B

MATTHew SHepaRD b. December 1, 1976 d. October 12, 1998 hero “Every American child deserves the strongest protections from some of the country’s most horrifying crimes.” – Judy Shepard As a gay college student, Matthew Shepard was the victim of a deadly hate crime. His Matthew Shepard’s murder brought national and international attention to the need for GLBT-inclusive hate crimes legislation. high-profile murder case sparked protests, vigils Shepard was born in Casper, Wyoming, to Judy and Dennis Shepard. He was the older of two sons. Matthew completed high school at The American School in Switzerland, and calls for federal hate and in 1998, he enrolled at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Soon afterward, crimes legislation for GLBT he joined the campus gay alliance. victims of violence. On October 6, 1998, two men—Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson—lured Shepard from a downtown Laramie bar. After Shepard acknowledged that he was gay, McKinney and Henderson beat and tortured him, then tied him to a fence in a remote, rural area and left him for dead. Eighteen hours later, a biker, who thought he saw a scarecrow, found Shepard barely breathing. Shepard was rushed to the hospital, but never regained consciousness. He died on October 12. Both of Shepard’s killers were convicted of felony murder and are serving two consecutive life sentences. Despite the outcome of the trial, the men who took Shepard’s life were not charged with a hate crime. Wyoming has no hate crimes law, which protects victims of crimes motivated by bias against a protected class.