Memory and Matthew Shepard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and Its Intercultural Implications

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2011 Proceedings of the 69th New York State Article 6 Communication Association 10-18-2012 Misunderstood: The aM tthew hepheS rd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Muir, Cameron (2012) "Misunderstood: The aM tthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2011, Article 6. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2011/iss1/6 This Undergraduate Student Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Muir: Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. national policy will develop. This essay serves as a continuation of this discussion, using the Matthew Shepherd hate crime, which occurred in October of 1998, as a focal point around which a detailed analysis of homophobia and masculinity in American culture will emerge. __________________________________________________________________ Synopsis The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. -

View / Open Final Thesis-Schukis H

AFTERLIVES (Gender)queer Photographic Self-Representation and Reenactment by HYACINTH SCHUKIS A CREATIVE THESIS Presented to the Department of Art and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts June 2020 An Abstract of the Thesis of Hyacinth Schukis (f.k.a. Allison Grace Schukis) for the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts with a concentration in Photography in the Department of Art to be taken June 2020 Title: Afterlives: (Gender)queer Photographic Self-Representation and Reenactment Approved: Colleen Choquette-Raphael Primary Thesis Advisor This thesis consists of a suite of photographic self-portraits and a critical introduction to the history of queer photographic self-representation through performative reenactment. The critical introduction theorizes that queer self- representation has a vested interest in history and its reenactment, whether as a disguise, or as a tool for political messaging and affirmations of existence. The creative component of the thesis is a series of large-scale color photographic self-portraits which reenact classic images from the history of “Western” art, with a marked interest in Catholic martyrdom and images previously used in queer artwork. As a whole, the photographs function as a series of identity-based historical reenactments, illustrated through performative use of the artist’s body and studio space. The photographs were intended for an exhibition that has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The thesis documents their current state, and discusses their symbolism and development. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor and mentor Colleen Choquette-Raphael for her generosity throughout my undergraduate education. -

VOL 04, NUM 17.Indd

“WISCONSIN” FROM SEVENTH PAGE who may not realize that marriage is already heterosexually defined. To say that this is a gay marriage amendment is grossly erroneous. In State of fact, this proposed amendment seeks to make it permanently impossible for us to ever seek civil unions or gay marriage. The proposed ban takes away rights—rights we do not even have. If our Disunion opposition succeeds, this will be the first time that PERCENT OF discrimination has gone into our state constitution. EQUAL RIGHTS YEAR OF OPENLY But our opposition will not succeed. I have GAY/LESBIAN been volunteering and working on this campaign AMERICA’S FIRST OCTOBER 2006 VOL. 4 NO. 17 DEATH SENTENCE STUDENTS for three years not because I have an altruistic that are forced to drop nature, but because I hold the stubborn conviction for sodomy: 1625 out: that fairness can prevail through successfully 28 combating ignorance. If I had thought defeating YEAR THAT this hate legislation was impossible, there is no way NUMBER OF I would have kept coming back. But I am grateful AMERICA’S FIRST SODOMY LAW REPORTED HATE that I have kept coming back because now I can be CRIMES a part of history. On November 7, turn a queer eye was enacted: 1636 in 2004 based on towards Wisconsin and watch the tables turn on the sexual orientation: conservative movement. We may be the first state to 1201 defeat an amendment like this, but I’ll be damned if YEAR THE US we’ll be the last. • SUPREME COURT ruled sodomy laws DATE THAT JERRY unconstitutional: FALWELL BLAMED A PINK EDITORIAL 2003 9/11 on homosexuals, pagans, merica is at another crossroads in its Right now, America is at war with Iraq. -

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

Matthew Shepard

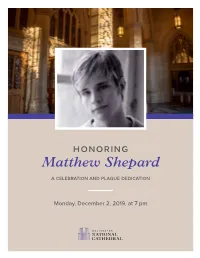

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

The Laramie Project

Special Thanks The Welcoming Project The The Welcoming Project is a Norman-based non-profit organization. The goal is to increase the visibility of LGBTQ- friendly welcoming places in Norman and worldwide. Laramie www.thewelcomingproject.org Project OU Counseling Psychology Clinic Screening and Discussion The purpose of the OU Counseling Psychology Clinic is to provide services to individuals, couples, families, and children involving various problems of living. Counseling services are charged on a sliding scale, based on familial income and the number of dependents. Anyone currently living in Oklahoma can come to the clinic for services. University affiliation is not necessary to receive services. For an appointment, call (405)325-2914. Women’s and Gender Studies Program, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies Program is an interdisciplinary program that seeks to enhance knowledge of gender roles and relations across cultures and history. http://wgs.ou.edu Center for Social Justice, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies’ Center for Social Justice 10.13.2016 seeks to promote gender justice, equality, tolerance, and human rights through local and global engagement. http://csj.ou.edu The Laramie Project, HBO Film October 12, 1998 Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Laramie, Laramie, WY, is a small town which became infamous overnight Wyoming, dies from severe injuries related to a in the fall of 1998, when Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, gruesome and violent hate crime attack he suffered was found tied to a fence after being brutally beaten and left to a few days earlier. die, setting off a nationwide debate about hate crimes and homophobia. -

The Ripple Effect of a Sexual Orientation Hate Crime :: the Psychological Impact of the Murder of Matthew Shepard on Non-Heterosexual People

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2000 The ripple effect of a sexual orientation hate crime :: the psychological impact of the murder of Matthew Shepard on non-heterosexual people. Monique Noelle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Noelle, Monique, "The ripple effect of a sexual orientation hate crime :: the psychological impact of the murder of Matthew Shepard on non-heterosexual people." (2000). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2354. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2354 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIPPLE EFFECT OF A SEXUAL ORIENTATION HATE CRIME: THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE MURDER OF MATTHEW SHEPARD ON NON-HETEROSEXUAL PEOPLE A Thesis Presented by MONIQUE NOELLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 2000 Department of Psychology © Copyright by Monique Noelle 2000 All Rights Reserved THE RIPPLE EFFECT OF A SEXUAL ORIENTATION HATE CRIME: THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE MURDER OF MATTHEW SHEPARD ON NON-HETEROSEXUAL PEOPLE A Thesis Presented by MONIQUE NOELLE Approved as to style and content by: Bonnie R. Strickland, Chair Richard P. Halgin, Member RoWieie JJafl^ff-Bulman, Member David M. Todd, Member Melinda Novak, Department Chair Psychology Department ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, thank you to the nine people who participated in the interview stage of this research for entrusting me with such deeply personal stories and feelings, and for sharing vision my of the importance of the questions addressed here. -

Combating Hate Crimes: Promoting a Re- Sponsive and Responsible Role for the Federal Government

S. HRG. 106±517 COMBATING HATE CRIMES: PROMOTING A RE- SPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING HOW TO PROMOTE A RESPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ON COMBATING HATE CRIMES, FOCUSING ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE STATES IN COMBATING HATE CRIME, ANALY- SIS OF STATES' PROSECUTION OF HATE CRIMES, DEVELOPMENT OF A HATE CRIME LEGISLATION MODEL, AND EXISTING FEDERAL HATE CRIME LAW MAY 11, 1999 Serial No. J±106±25 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 64±861 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MANUS COONEY, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hatch, Hon. -

INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY Copyright 2004, the Graduate School of Syracuse University

>>>>>> >>>>>> INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY Copyright 2004, The Graduate School of Syracuse University. Portions of this publication may be reproduced with acknowledgment for educational purposes. For more information about this publication, contact the Graduate School at Syracuse University, 423 Bowne Hall, Syracuse, New York 13244. >> contents Acknowledgments................................................................................... i Vice Chancellor’s Preface DEBORAH A. FREUND...................................................................... iii Editors’ Introduction MARY QUEEN, KATHLEEN FARRELL, AND NISHA GUPTA ............................ 1 PART ONE: INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY FRAMING THE ISSUES Heteronormativity and Teaching at Syracuse University SUSAN ADAMS.............................................................................. 13 Cartography of (Un)Intelligibility: A Migrant Intellectual’s Tale of the Field HUEI-HSUAN LIN............................................................................ 21 The Invisible Presence of Sexuality in the Classroom AHOURA AFSHAR........................................................................... 33 LISTENING TO STUDENTS (Un)Straightening the Syracuse University Landscape AMAN LUTHRA............................................................................... 45 Echoes of Silence: Experiences of LGBT College Students at SU RACHEL MORAN AND BRIAN STOUT..................................................... 55 The Importance of LGBT Allies CAMILLE BAKER............................................................................ -

Matthew Shepard Papers

Matthew Shepard Papers NMAH.AC.1463 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Content Description.......................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Shepard, Matthew, Personal Papers, 1976-2019, undated...................... 5 Series 2: Shepard Family and The Matthew Shepard Foundation, Papers and Correspondence Received, 1998-2013, undated................................................... 12 Series 3: Tribute, Vigil, and Memorial Services, Memorabilia, and Inspired Works, 1998-2008, undated.............................................................................................. -

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Issues Conference

CALIFORNIA TEACHERS ASSOCIATION GAY, LESBIAN, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ISSUES CONFERENCE DECEMBER 9-11, 2016 | RIVIERA HOTEL, PALM SPRINGS The CTA Foundation for Teaching & Learning It’s about supporting educators, students and schools. It’s about innovative changes now! The CTA Foundation for Teaching & Learning includes three areas of support for educators, students and schools. 1. CTA’s Institute for Teaching (IFT) supports strength-based educator driven change; 2. CTA’s Disaster Relief Program provides direct financial assistance to members experiencing significant losses due to natural disasters in California; 3. CTA’s scholarships and grant programs includes Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Scholarships, César E. Chávez Awards, GLBT Safety in Schools Grants & Scholarships, and various other scholarships for SCTA members and children of CTA members. More than 160 scholarships, awards, and grants are available through CTA each year. Thanks to the generous contributions of CTA members, more than $350,000 was awarded in scholarships and grants last year and more than $170,000 has been granted to CTA members in need through the Disaster Relief Fund. For more information, go to www.cta.org or contact your local RRC or UniServ office. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page General Information. 1 CTA Directorial Districts Map. 2 CTA Board of Directors & NEA Directors from California. 3 Conference Planning Committee & Conference Staff . 4 Agenda Friday, December 9 . 5 Saturday, December 10. 6 Sunday, December 11. 7 Your Personal Conference Schedule. 8 Sessions-at-a-Glance. 9 Session Descriptions. 10-16 Caucuses and Forums . 17-18 LGBTQ+ Vocabulary Definitions . 19-23 Biographies Eric C. Heins, CTA President . -

The Laramie Project

Special Thanks The Welcoming Project The The Welcoming Project is a Norman-based non-profit organization. The goal is to increase the visibility of LGBTQ- friendly welcoming places in Norman and worldwide. Laramie www.thewelcomingproject.org Project OU Counseling Psychology Clinic Screening and Discussion The purpose of the OU Counseling Psychology Clinic is to provide services to individuals, couples, families, and children involving various problems of living. Counseling services are charged on a sliding scale, based on familial income and the number of dependents. Anyone currently living in Oklahoma can come to the clinic for services. University affiliation is not necessary to receive services. For an appointment, call (405)325-2914. Women’s and Gender Studies Program, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies Program is an interdisciplinary program that seeks to enhance knowledge of gender roles and relations across cultures and history. http://wgs.ou.edu Center for Social Justice, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies’ Center for Social Justice 10.17.2013 seeks to promote gender justice, equality, tolerance, and human rights through local and global engagement. http://csj.ou.edu The Laramie Project, HBO Film October 12, 1998 Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Laramie, Laramie, WY, is a small town which became infamous overnight Wyoming, dies from severe injuries related to a in the fall of 1998, when Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, gruesome and violent hate crime attack he suffered was found tied to a fence after being brutally beaten and left to a few days earlier. die, setting off a nationwide debate about hate crimes and homophobia.