The Laramie Project – Teacher's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and Its Intercultural Implications

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2011 Proceedings of the 69th New York State Article 6 Communication Association 10-18-2012 Misunderstood: The aM tthew hepheS rd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Muir, Cameron (2012) "Misunderstood: The aM tthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2011, Article 6. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2011/iss1/6 This Undergraduate Student Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Muir: Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. national policy will develop. This essay serves as a continuation of this discussion, using the Matthew Shepherd hate crime, which occurred in October of 1998, as a focal point around which a detailed analysis of homophobia and masculinity in American culture will emerge. __________________________________________________________________ Synopsis The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. -

View / Open Final Thesis-Schukis H

AFTERLIVES (Gender)queer Photographic Self-Representation and Reenactment by HYACINTH SCHUKIS A CREATIVE THESIS Presented to the Department of Art and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts June 2020 An Abstract of the Thesis of Hyacinth Schukis (f.k.a. Allison Grace Schukis) for the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts with a concentration in Photography in the Department of Art to be taken June 2020 Title: Afterlives: (Gender)queer Photographic Self-Representation and Reenactment Approved: Colleen Choquette-Raphael Primary Thesis Advisor This thesis consists of a suite of photographic self-portraits and a critical introduction to the history of queer photographic self-representation through performative reenactment. The critical introduction theorizes that queer self- representation has a vested interest in history and its reenactment, whether as a disguise, or as a tool for political messaging and affirmations of existence. The creative component of the thesis is a series of large-scale color photographic self-portraits which reenact classic images from the history of “Western” art, with a marked interest in Catholic martyrdom and images previously used in queer artwork. As a whole, the photographs function as a series of identity-based historical reenactments, illustrated through performative use of the artist’s body and studio space. The photographs were intended for an exhibition that has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The thesis documents their current state, and discusses their symbolism and development. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor and mentor Colleen Choquette-Raphael for her generosity throughout my undergraduate education. -

Drama Book Shop Became an Independent Store in 1923

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION SALUTING A UNIQUE INSTITUTION ♦ Monday, November 26 Founded in 1917 by the Drama League, the Drama Book Shop became an independent store in 1923. Since 2001 it has been located on West 40th Street, where it provides a variety of services to the actors, directors, producers, and other theatre professionals who work both on and off Broadway. Many of its employees THE PLAYERS are young performers, and a number of them take part in 16 Gramercy Park South events at the Shop’s lovely black-box auditorium. In 2011 Manhattan the store was recognized by a Tony Award for Excellence RECEPTION 6:30, PANEL 7:00 in the Theatre . Not surprisingly, its beneficiaries (among them Admission Free playwrights Eric Bogosian, Moises Kaufman, Lin-Manuel Reservations Requested Miranda, Lynn Nottage, and Theresa Rebeck), have responded with alarm to reports that high rents may force the Shop to relocate or close. Sharing that concern, we joined The Players and such notables as actors Jim Dale, Jeffrey Hardy, and Peter Maloney, and writer Adam Gopnik to rally support for a cultural treasure. DAKIN MATTHEWS ♦ Monday, January 28 We look forward to a special evening with DAKIN MATTHEWS, a versatile artist who is now appearing in Aaron Sorkin’s acclaimed Broadway dramatization of To Kill a Mockingbird. In 2015 Dakin portrayed Churchill, opposite Helen Mirren’s Queen Elizabeth II, in the NATIONAL ARTS CLUB Broadway transfer of The Audience. -

VOL 04, NUM 17.Indd

“WISCONSIN” FROM SEVENTH PAGE who may not realize that marriage is already heterosexually defined. To say that this is a gay marriage amendment is grossly erroneous. In State of fact, this proposed amendment seeks to make it permanently impossible for us to ever seek civil unions or gay marriage. The proposed ban takes away rights—rights we do not even have. If our Disunion opposition succeeds, this will be the first time that PERCENT OF discrimination has gone into our state constitution. EQUAL RIGHTS YEAR OF OPENLY But our opposition will not succeed. I have GAY/LESBIAN been volunteering and working on this campaign AMERICA’S FIRST OCTOBER 2006 VOL. 4 NO. 17 DEATH SENTENCE STUDENTS for three years not because I have an altruistic that are forced to drop nature, but because I hold the stubborn conviction for sodomy: 1625 out: that fairness can prevail through successfully 28 combating ignorance. If I had thought defeating YEAR THAT this hate legislation was impossible, there is no way NUMBER OF I would have kept coming back. But I am grateful AMERICA’S FIRST SODOMY LAW REPORTED HATE that I have kept coming back because now I can be CRIMES a part of history. On November 7, turn a queer eye was enacted: 1636 in 2004 based on towards Wisconsin and watch the tables turn on the sexual orientation: conservative movement. We may be the first state to 1201 defeat an amendment like this, but I’ll be damned if YEAR THE US we’ll be the last. • SUPREME COURT ruled sodomy laws DATE THAT JERRY unconstitutional: FALWELL BLAMED A PINK EDITORIAL 2003 9/11 on homosexuals, pagans, merica is at another crossroads in its Right now, America is at war with Iraq. -

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

Matthew Shepard

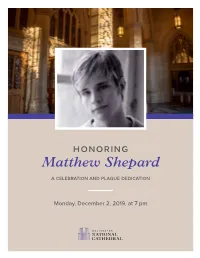

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

The Laramie Project

Special Thanks The Welcoming Project The The Welcoming Project is a Norman-based non-profit organization. The goal is to increase the visibility of LGBTQ- friendly welcoming places in Norman and worldwide. Laramie www.thewelcomingproject.org Project OU Counseling Psychology Clinic Screening and Discussion The purpose of the OU Counseling Psychology Clinic is to provide services to individuals, couples, families, and children involving various problems of living. Counseling services are charged on a sliding scale, based on familial income and the number of dependents. Anyone currently living in Oklahoma can come to the clinic for services. University affiliation is not necessary to receive services. For an appointment, call (405)325-2914. Women’s and Gender Studies Program, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies Program is an interdisciplinary program that seeks to enhance knowledge of gender roles and relations across cultures and history. http://wgs.ou.edu Center for Social Justice, University of Oklahoma The Women’s and Gender Studies’ Center for Social Justice 10.13.2016 seeks to promote gender justice, equality, tolerance, and human rights through local and global engagement. http://csj.ou.edu The Laramie Project, HBO Film October 12, 1998 Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Laramie, Laramie, WY, is a small town which became infamous overnight Wyoming, dies from severe injuries related to a in the fall of 1998, when Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, gruesome and violent hate crime attack he suffered was found tied to a fence after being brutally beaten and left to a few days earlier. die, setting off a nationwide debate about hate crimes and homophobia. -

Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas International Conference Program, June 15-18, 20003 Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas LMDA Conferences LMDA Archive 2000 Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas International Conference Program, June 15-18, 20003 Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/lmdaconferences Recommended Citation Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas, "Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas International Conference Program, June 15-18, 20003" (2000). LMDA Conferences. 2. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/lmdaconferences/2 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the LMDA Archive at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMDA Conferences by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Conference, 2000 Starting At ‘00: the dramaturg as creator Thursday, June 15 to Sunday, June 18 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Conference Goals . to affirm the function, explore the practice, and promote the profession We are extremely fortunate to be hosted this year by Kristin Johnsen-Neshati and the Theater Division of the Institute of the Arts at George Mason University, a beautiful campus just west of Washington, DC. Our conference this year begins with the assumption that dramaturgy is creative and generative, a way of making. We come together to consider the forms this creativity takes and its implications for the field. Conference chairs Jane Ann Crum and Brian Quirt have invited special guests that provide innovative models of creative dramaturgy: (in order of appearance) Moisés Kaufman, Paul Lazar, Annie-B Parson, and Anne Cattaneo. Liz Engelman has organized eight professional practice forums around the concept of the dramaturg as creator. -

Research Essay for Eckles Prize for Freshman Research Excellence I

Research Essay for Eckles Prize for Freshman Research Excellence I first thought of my research topic when several of the girls in my hall decided to watch the movie Brokeback Mountain and were met with a response from fellow residents that was anything but subtle. With reactions of disgust from the boys, condemning the film as “gay porn,” and accusing rebuttals from the girls as they pointed out the boys’ fascination with “Girls Gone Wild,” the exchange begged several questions about our American culture. Why is female homosexuality attractive, while male homosexuality is regarded with disgust by particular audiences? Why is the acceptance of homosexuality limited to overtly sexual encounters, as implied by my peers’ reaction, and discludes the realm of lifetime/serious relationships, as represented in the film? How widespread are these patterns and points of view and what is the media’s role in this? As you will soon see, this was by no means the final direction my project went, but merely a jumping off point for a greater project, which for me was one of the most intellectually stimulating experiences of my academic career. These questions and the ones they inspired opened my eyes not only to a discipline that examined different interpretations of sexuality, identity, and acceptance in ways in which I had never explored, but also a new approach to analyzing the world around me. As described above, my original idea was to explore how the media has shaped the dominant culture’s view of homosexuals through an examination of the film Brokeback Mountain , its subsequent reviews, and the effect it has had on “typical” American perceptions of male and female homosexuality. -

Combating Hate Crimes: Promoting a Re- Sponsive and Responsible Role for the Federal Government

S. HRG. 106±517 COMBATING HATE CRIMES: PROMOTING A RE- SPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING HOW TO PROMOTE A RESPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ON COMBATING HATE CRIMES, FOCUSING ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE STATES IN COMBATING HATE CRIME, ANALY- SIS OF STATES' PROSECUTION OF HATE CRIMES, DEVELOPMENT OF A HATE CRIME LEGISLATION MODEL, AND EXISTING FEDERAL HATE CRIME LAW MAY 11, 1999 Serial No. J±106±25 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 64±861 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MANUS COONEY, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hatch, Hon. -

Police Abuse and Misconduct Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the U.S

United States of America Stonewalled : Police abuse and misconduct against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the U.S. 1. Introduction In August 2002, Kelly McAllister, a white transgender woman, was arrested in Sacramento, California. Sacramento County Sheriff’s deputies ordered McAllister from her truck and when she refused, she was pulled from the truck and thrown to the ground. Then, the deputies allegedly began beating her. McAllister reports that the deputies pepper-sprayed her, hog-tied her with handcuffs on her wrists and ankles, and dragged her across the hot pavement. Still hog-tied, McAllister was then placed in the back seat of the Sheriff’s patrol car. McAllister made multiple requests to use the restroom, which deputies refused, responding by stating, “That’s why we have the plastic seats in the back of the police car.” McAllister was left in the back seat until she defecated in her clothing. While being held in detention at the Sacramento County Main Jail, officers placed McAllister in a bare basement holding cell. When McAllister complained about the freezing conditions, guards reportedly threatened to strip her naked and strap her into the “restraint chair”1 as a punitive measure. Later, guards placed McAllister in a cell with a male inmate. McAllister reports that he repeatedly struck, choked and bit her, and proceeded to rape her. McAllister sought medical treatment for injuries received from the rape, including a bleeding anus. After a medical examination, she was transported back to the main jail where she was again reportedly subjected to threats of further attacks by male inmates and taunted by the Sheriff’s staff with accusations that she enjoyed being the victim of a sexual assault.2 Reportedly, McAllister attempted to commit suicide twice. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks on Presenting The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks on Presenting the National Medal of Arts and the National Humanities Medal September 22, 2016 The President. Thank you! Everybody, please have a seat, have a seat. Thank you so much. Everybody, please sit down. I can tell this is a rowdy crowd. Sit down. [Laughter] Welcome to the White House, everybody. Now, throughout my time here, Michelle and I have tried to make it a priority to promote the arts and the humanities, especially for our young people, and it's because we believe that the arts and the humanities are, in many ways, reflective of our national soul. They're central to who we are as Americans: dreamers and storytellers and innovators and visionaries. They're what helps us make sense of the past, the good and the bad. They're how we chart a course for the future while leaving something of ourselves for the next generation to learn from. And we are here today to honor the very best of their fields, creators who give every piece of themselves to their craft. As Mel Brooks once said—[laughter]—to her—to his writers on "Blazing Saddles," which is a great film: "Write anything you want, because we'll never be heard from again. We will all be arrested for this movie." [Laughter] Now, to be fair, Mel also said, a little more eloquently, that "every human being has hundreds of separate people living inside his skin. And the talent of a writer is his ability to give them their separate names, identities, personalities and have them relate to other characters living within him." And that, I think, is what the arts and the humanities do.