Tremona Castle: a Window on History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elenco Dei Membri Effetivi Della Società Degli Amici Dell'educazione Del Popolo : Al 1. Gennaio 1872

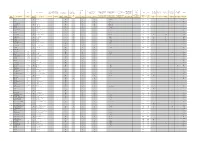

Elenco dei membri effetivi della Società degli amici dell'educazione del popolo : al 1. gennaio 1872 Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Appendix Zeitschrift: L'educatore della Svizzera italiana : giornale pubblicato per cura della Società degli amici dell'educazione del popolo Band (Jahr): 14 (1872) Heft 3 PDF erstellt am: 09.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch ELENCO DEI MEMBRI EFFETTIVI DELLA SOCIETÀ' DEGLI AMICI DELL' EDUCAZIONE DEL POPOLO Ah II* GF..\.\.U0 1872 o a Cognome e Nome Condizione Patkia Domicilio m fi Commissione Uirigen'e pel Biennio X—73-73. Battaglini C, Presidente Avvocato Cagiallo Lugau« 1858 Ferri Giov., Viee-Presid. -

PDB COLCVA Allegato9

Inserire poli attrattori serviti: Indicare punta / morbida Scuole superiori Specificare se il PdB prevede 1 = primario, linea strutturante della rete G = 365 18 = > 18 ore 15' Cad Sim= cadenzato con simmetria 00 Indicare attuali punti di intersezione e Indicare futuri punti di intersezione e SI = <10' e simmetriche Università variazione percorrenze specifici vincoli di continuità tra Percorrenze variazione delle variazione percorrenze variazione percorrenze variazione percorrenze 2 = secondaria, linea di afferenza strutturata Fer = feriale 5 o 6 15 = tra 14 e 17 ore 30' Cad = cadenzato rete (SFR, M, T, FUN, NAV). rete (SFR, M, T, FUN, NAV) NO = > 10' o <10' ma non simmetriche Ospedali dovuta al reintegro dei Percorrenze Programmate Legenda: Inserire dato Indicare solo se diverso da SdF sistemi (ad esempio bus in Percorrenze 2017 Programmate percorrenze dovute a dovuta al potenziamento dovuta al potenziamento dovuta al potenziamento 3 = terziaria, linea prevalent.scolastica o marginale Scol = prevalent. scolastico P = punta 3 fasce (8/12/18) 60' Sp = frequenza specifica e irregolare In caso di più interscambi aggiungere In caso di più interscambi aggiungere NS = non specificabile (per linee ad intervalli Centri commerciali servizi festivi e nei fine (a regime) partenza ad ogni tram o (1° anno PdB) particolari interventi degli Rlink delle linee primarie delle linee secondarie 4 = flessibile, linea gestita con modalità specifiche P = periodico (stagionale) S = scolastica 2 fasce (8/12) 120' Fq = a frequenza (<15') linee sottostanti linee -

Deliberazione Del Consiglio Comunale

COMUNE DI SALTRIO Provincia di Varese DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE N. 5 Reg. Delib. OGGETTO: CONVENZIONE TRA I COMUNI DI ANGERA, SALTRIO, BARASSO E LUVINATE PER L'ESERCIZIO CONGIUNTO DELL'UFFICIO DI SEGRETERIA COMUNALE. APPROVAZIONE. L’anno duemilaventuno, addì ventisette del mese di febbraio alle ore 10.00, nella sede comunale. Previa notifica degli inviti personali, avvenuta nei modi e termini di legge, si è riunito il Consiglio Comunale in sessione ed in seduta PUBBLICA di prima convocazione. SINDACO ZANUSO Maurizio Presente CONSIGLIERE FRANZI Giuseppe Presente CONSIGLIERE REALINI DONATELLA Presente CONSIGLIERE CASTELLANO Nicolò Presente CONSIGLIERE STASI SALVATORE Presente CONSIGLIERE ROMELLI Marco Assente CONSIGLIERE SCALCIONE Amanda Presente CONSIGLIERE SGRÒ Daniela Assente CONSIGLIERE DE VITTORI LUIGI Assente CONSIGLIERE SARTORELLI ANTONIO Presente CONSIGLIERE LETO BARONE GIUSEPPE Assente CONSIGLIERE COCCHI Diego Assente CONSIGLIERE CHIOFALO Salvatore Presente Totale presenti n. 8 Totale assenti n. 5 Partecipa con funzioni consultive, referenti, di assistenza e verbalizzazione, ai sensi dell’art. 97, quarto comma, lettera a), del d.lgs. 18.08.2000, n. 267, il Segretario Comunale sig. dott. Giuseppe CARDILLO. Il sig. ing. Maurizio ZANUSO – Sindaco, assunta la presidenza e constatata la legalità dell’adunanza, dichiara aperta la seduta e pone in discussione la seguente pratica segnata all’ordine del giorno: IL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE UDITO il consigliere comunale di minoranza Sartorelli Antonio, il quale ringrazia il segretario -

Ottobre 2020

NUMERO 07 ALFANotizie Notiziario delle principali attività svolte da Alfa S.r.l. per tipologia di servizio OTTOBRE 2020 Acquedotto ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 04 Attività La gestione dell’acquedotto è passata ad Alfa. Comuni interessati: Agra Dumenza Brissago Valtravaglia Ferrera di Varese Brusimpiano Montegrino Valtravaglia Cassano Valcuvia Porto Ceresio Castelveccana Rancio Valcuvia Curiglia Monteviasco Tronzano Lago Maggiore ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 05 Attività Interventi d’urgenza per il ripristino della fornitura a seguito delle interruzioni d’energia elettrica causate dal maltempo. Comuni interessati: Agra Gavirate Angera Gemonio Besozzo Laveno Mombello Casale Litta Mesenzana Cittiglio Saltrio Cuveglio Taino Duno ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 06 Attività Installazione di un nuovo avviatore, collegamento di nuove pompe e rifacimento del piping al rilancio Brusnago. Comune interessato: Azzio Rilancio Brusnago ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 07 Attività • Effettuato cambio carboni al pozzo Samarate. • Installate pompette di dosaggio del cloro per la disinfezione in tutti gli impianti. Comune interessato: Busto Arsizio ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 08 Attività Installazione di inverter resettabili da remoto al pozzo Firello 1 di Casale Litta. Comune interessato: Casale Litta Casale Litta Firello 1 Reset da remoto ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 09 Attività Installazione d’urgenza di una pompa di rilancio al serbatoio Menasi per far fronte a carenze idriche. Quest’ultima permette di supportare l’apporto sorgivo al serbatoio Martinello. Comune interessato: Castello Cabiaglio Serbatoio Menasi ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 10 Attività Sostituzione pressostati guasti e azionatore di potenza pompa 2 all’autoclave Vallè. Comune interessato: Gemonio Autoclave Vallè ALFANotizie Acquedotto! 11 Attività Installazione di pompette dosatrici del cloro al serbatoio Mondizza di Grantola. Comune Attività interessato: Installazione di un nuovo impianto di clorazione Grantola presso i pozzi S. -

20° Anniversario Di Tandem 4 Professioni in Campo 5 Attività Manuali 6 Attività Sportive15 Di Tutto Un Po'20 Visite E Feste

QR Code App gratuita Tandem Spicchi di vacanza 6828 Balerna [email protected] monoparentali e ricostituite www.tandem-ticino.ch viale Pereda 1 Associazione ticinese delle famiglie famiglie Associazione delle ticinese estate 2016 vacanza di – Spicchi Tandem c/o CH 20° anniversario Tandem di Tandem 4 compie 20 anni! Professioni in campo 5 Sabato 3 settembre 2016 Attività manuali 6 facciamo Attività sportive 15 una festa campestre Di tutto un po’ 20 a Mendrisio Visite e feste 28 con tanti laboratori Musica, danza, giochi all’aperto teatro e cinema 29 spettacoli di musica Nella natura 39 e di teatro Campi diurni 43 Colonie residenziali 50 Visita il sito www.tandem-ticino.ch 1. guarda le foto delle attività di animazione 2. guarda sulla mappa dov’è il luogo dell’attività 3. cerca gli aggiornamenti dei corsi 4. iscriviti online al corso che preferisci Tandem è su Facebook: Tandem Spicchi Di Vacanza Tandem – Spicchi di vacanza 2016 Tandem – Spicchi di vacanza 2016 2 3 Novità 2016 Programma “Acque sicure” Il Dipartimento delle istituzioni ha allestito un programma di informazione e prevenzione, destinato a residenti e turisti, legato alla fruibilità- dei corsi d’acqua e dei bacini lacustri, in cui vengono in particolare messi in evidenza i pericoli insiti nei fiumi e nei laghi del nostro Cantone allo scopo di promuovere una balnea zione corretta e sicura e di ridurre gli incidenti Care amiche e cari amici di Tandem, Tandem–Spicchi di Per la realizzazione che avvengono nelle acquePartner ticinesi (pag. 55). Per il finanziamento 1996–2016 principale -

Elezione Consiglio Comunale 18 Aprile 2021 Proposta N. 2: Partito Liberale Radicale E GLR

Elezione Consiglio comunale 18 aprile 2021 Proposta n. 2: Partito Liberale Radicale e GLR ELENCO CANDIDATI DATA DI NO. COGNOME NOME DOMICILIO QUARTIERE NASCITA CIRCONDARIO N. 1 (Mendrisio Borgo-Salorino) 1 Bernasconi Luca 14.11.1975 Mendrisio Mendrisio 2 Bianchi Giacomo 12.12.1971 Mendrisio Mendrisio 3 Bordogna Niccolò 23.01.1994 Mendrisio Mendrisio 4 Brenni Tonella Raffaella 13.10.1970 Mendrisio Salorino 5 Capiaghi Alessio 12.04.1980 Mendrisio Mendrisio 6 Cattaneo Katia 06.11.1974 Mendrisio Mendrisio 7 Cavadini Samuele 25.03.1979 Mendrisio Salorino 8 Cerutti Massimo 01.10.1962 Mendrisio Mendrisio 9 Crimaldi Gianluca 04.03.1989 Mendrisio Mendrisio 10 Crimaldi Vincenzo 26.07.1980 Mendrisio Mendrisio 11 Delucchi Andrea Francesco 24.04.1981 Mendrisio Mendrisio 12 Engeler Beatrice 05.08.1974 Mendrisio Mendrisio 13 Engeler Dario 10.07.1973 Mendrisio Mendrisio 14 Fumagalli Daniele 19.04.1977 Mendrisio Mendrisio 15 Guarneri Andrea 24.10.1965 Mendrisio Mendrisio 16 Lombardo Lorenzo 19.10.1971 Mendrisio Mendrisio 17 Lordelli Matteo 05.10.1997 Mendrisio Mendrisio 18 Pestelacci Luca 25.07.1987 Mendrisio Mendrisio 19 Pestoni Federico 17.08.1982 Mendrisio Salorino 20 Ponti Gabriele 27.06.1974 Mendrisio Salorino 21 Rezzonico Cristina 03.05.1972 Mendrisio Mendrisio 22 Rezzonico Nicola 12.09.1970 Mendrisio Mendrisio 23 Rusconi Mario 13.12.1961 Mendrisio Mendrisio 24 Schmidt Paolo 04.10.1972 Mendrisio Mendrisio 25 Selvaratnam Nitharsana 03.10.1992 Mendrisio Mendrisio CANCELLERIA COMUNALE DI MENDRISIO Il Sindaco 1 Elezione Consiglio comunale 18 aprile 2021 Proposta n. 2: Partito Liberale Radicale e GLR DATA DI NO. COGNOME NOME DOMICILIO QUARTIERE NASCITA 26 Sisini Cesare 24.12.1968 Mendrisio Mendrisio 27 Stoppa Francesco 15.05.1991 Mendrisio Mendrisio 28 Tettamanti Stefano 04.03.1989 Mendrisio Mendrisio CIRCONDARIO N. -

Arte. Antichità. Argenti. Le Collezioni Di Giovanni Züst Nei Musei Di Rancate, Basilea E San Gallo

6862 Rancate (Mendrisio) Dipartimento dell'educazione, della cultura e dello sport Cantone Ticino - Svizzera Divisione della cultura e degli studi universitari telefono +41 91 816 47 91 e-mail [email protected] fax +41 91 816 47 99 url www.ti.ch/zuest Pinacoteca cantonale Giovanni Züst Arte. Antichità. Argenti. Le collezioni di Giovanni Züst nei musei di Rancate, Basilea e San Gallo COMUNICATO STAMPA Progetto realizzato dal Dipartimento dell’educazione della cultura e dello sport grazie all’Aiuto federale per la salvaguardia e promozione della lingua e cultura italiana Coordinamento generale del progetto: Paola Piffaretti, Divisione della cultura e degli studi universitari Sede: Pinacoteca cantonale Giovanni Züst, Rancate (Mendrisio), Canton Ticino, Svizzera Date: 20 marzo – 28 agosto 2016 Mostra a cura di: Mariangela Agliati Ruggia Coordinamento scientifico e organizzativo: Alessandra Brambilla, Esaù Dozio Allestimento Progettazione: Arch. Rolando Zuccolo, Besazio, con l’assistenza di Julian Panfili Realizzazione: Sezione della logistica e Piercarlo Bortolotti Decorazioni murali: Luca Bianchi, Lina Echeverry, Chiara Ottavi In questa occasione è stato realizzato un volume celebrativo in due lingue (italiano e tedesco) ________________________________________________________________ La mostra riunisce per la prima volta le collezioni d’arte che Giovanni Züst (Basilea, 1887 - Rancate, 1976), figura complessa di imprenditore filantropo, donò a enti pubblici svizzeri: il Cantone Ticino (1966), che avrebbe quindi aperto la Pinacoteca cantonale Giovanni Züst di Rancate, il Cantone di Basilea-Città (1959), che ricevette così l’impulso per la creazione dell’Antikenmuseum di Basilea, la città di San Gallo (1967). Il percorso espositivo si snoda tra rare e preziose antichità etrusche, greche e romane, strepitosi argenti dei secoli XVI-XVIII e dipinti di Serodine, Petrini e dei protagonisti dell’Ottocento ticinese (Rinaldi, Luigi Rossi, Ernesto Fontana, Galbusera), accompagnando il visitatore alla scoperta del gusto vario e raffinato di Giovanni Züst. -

Il Sistema Di Trasporto Pubblico Locale

Con il contributo di COMUNE DI CADREZZATE (Capofila) Provincia di Varese Angera, Brebbia, Bregano, Cadrezzate, Comabbio, Ispra, Laveno Mombello, Leggiuno, Mercallo, Monvalle, Osmate, Ranco, Taino, Varano Borghi. Piano della Mobilità Sostenibile per i Comuni dell’Area di AGENDA 21 LAGHI Pianificazione dei miglioramenti per il TPL Gruppo di progettazione: Progettisti: S.I.P.E.T. Arch. Nicola D’Errico (Capogruppo) S.I.P.E.T. Arch. Giusy Zaccheo Architettura Urbanistica Mobilità Trasporti Arch. Enrico Eugenio D’Errico Studio Interprofessionale per la Progettazione e la Programmazione Economico-Territoriale SISTeMA Via Gabriele Pepe, 23 - 86039 Termoli(CB) Ing. Lorenzo Meschini Tel 0875 705972 - Fax 0875 706618 Prof. Ing. Guido Gentile www.sipet.it Collaboratori: Ing. Domingo Lunardon studio associato SISTeMA Servizi per l’Ingegneria dei Sistemi di Trasporto e della Mobilità Lungotevere Portuense, 158 – 00153 Roma (RM) Tel 06.835.115.26 - Fax 06.892.826.80 www.sistema-trasporti.com COMUNE DI CADREZZATE Piano della Mobilità Sostenibile per i Comuni dell’Area di AGENDA 21 LAGHI PIANIFICAZIONE DEI MIGLIORAMENTI PER IL TPL Indice 1 Introduzione ................................................................................................................ 3 2 L’offerta di trasporto della rete TPL ............................................................................... 4 2.1 La rete di trasporto su gomma ............................................................................... 4 2.2 La rete di trasporto su ferro .................................................................................. -

La Voce Dell'appacuvi

LA VOCE DELL’APPACUVI ANNO 6, NUMERO 29 - DICEMBRE 2009 Foglio informativo dell’Associazione per la Protezione del Patrimonio Artistico e Culturale Valle Intelvi Direttore responsabile Ernesto Palmieri; Direttore editoriale Livio Trivella. Hanno collaborato a questo numero: Rosa Maria Corti, Andrea Spiriti, Vittorio Peretto (V.P.) Rosa Travella Segreteria di Redazione: Valentina Mattazzi MESSAGGI ED APPROFONDIMENTI Comunità montane addio Lo scorso 19 novembre, il Consiglio dei Ministri ha approvato il Disegno di Legge sulla riforma degli organi e delle funzioni degli enti locali, di semplificazione e ra- zionalizzazione dell'ordinamento e la Carta delle autonomie locali. Questa riforma - a detta del Ministro competente - porterà all’eliminazione di migliaia di enti dan- nosi ed al taglio di circa 34mila tra consiglieri comunali, circoscrizionali e provin- ciali e di circa 15 mila assessori comunali e provinciali, con consistenti risparmi di spese per la macchina pubblica e un complessivo snellimento delle strutture ammi- nistrative. Dal 2010, inoltre, le Regioni potranno sopprimere le Comunità monta- ne, isolane e di arcipelago. In ogni caso, lo Stato cesserà di concorrere al finanzia- mento delle Comunità montane, quindi, se una Regione vorrà mantenerle in vita, dovrà anche provvedere al loro finanziamento. Risparmio e snellimento sembrano essere le parole d’ordine dalle quali, per la verità, è difficile dissentire. Ma, tuttavia, c’è in questo disegno qualcosa che non convince fino in fondo. Bene l’eliminazio- ne degli enti dannosi (una -

Itinerari Culturali IT

Itinerari culturali. Cultural itineraries. Le curiosità storiche della regione. The historical curiosities of the region. I / E Basso Mendrisiotto | 1 2 | Basso Mendrisiotto La Regione da scoprire. Le curiosità storiche della regione. The historical curiosities of the region. Rendete il vostro soggiorno interessante! Five routes to add interest to your stay! Cinque itinerari storico culturali sono stati disegna- Five cultural routes in the region of Mendrisiotto and ti nella Regione del Mendrisiotto e Basso Ceresio Basso Ceresio have been developed to take you on per accompagnarvi nella scoperta dei diversi co- a journey of discovery through various towns and muni e villaggi, per svelare le eccellenze e le curio- villages where you will see the sights and curiosities sità legate a luoghi, avvenimenti e persone che of places, events and people, and learn about their hanno avuto ruoli, o svolto compiti, importanti. important roles. I testi inseriti nelle isole informative lungo i cinque Along the five routes, you will find information points itinerari sono stati redatti da tre storici che, in stretta with texts and pictures from both public and private collaborazione con Mendrisiotto Turismo ed i comu- archives, prepared by three historians, together ni della regione, si sono anche occupati della scelta with Mendrisiotto Tourism and the municipalities of del materiale fotografico, reperito in prevalenza da the region. As a rule, each information point has archivi pubblici e privati. Di regola, le isole didattiche three double-sided boards, and presents the route, inserite nelle tappe dei cinque itinerari, sono compo- the history of the place, three points of interest and ste da tre pannelli bifacciali e presentano ciascuno: a curiosity (excepting: Morbio Superiore, Sagno, l’itinerario, la storia del luogo-paese, tre eccellenze Scudellate, Casima, Monte and Corteglia). -

Cantiere SP. 14

PROVINCIA DI COMO SETTORE INFRASTRUTTURE A RETE E PUNTUALI VIA BORGOVICO, 148 - 22100 COMO – TEL. 031/230.111 – pec. [email protected] Protocollo N. 11017 Como, 18 marzo 2021 Class.: 11.15.09 Fasc.: 1 OGGETTO : ORDINANZA N°18/ 2021 Ufficio Tecnico S.P. 14 “SAN FEDELE-OSTENO-PORLEZZA” – tratte puntuali in Comune di Claino con Osteno e Laino- LAVORI DI MANUTENZIONE STRAORDINARIA DEI DISPOSITIVI DI RITENUTA LATERALE NELLE ZONE DI MONTAGNA – LOTTO 1 (D.G.R. XI/3113). IMPRESA APPALTATRICE: DAPAM S.R.L. con sede in Via Ponte d’Uscio 2/C – 25042 Borno (BS)– CONTRATTO: n°38530 di Rep. in data 24/11/2020 di Euro 581.564,80 – CIG 8382066BAC- Consegna lavori il 29/10/2020 - Apertura cantiere stradale per esecuzione lavori - IL DIRIGENTE DEL SETTORE INFRASTRUTTURE A RETE E PUNTUALI VISTI: • il D.L.vo n° 285 (Nuovo Codice della Strada. agli articoli 5, 6 e 7 e s.m.i ; • l’art. 107 del D.L. 267 del 18/08/2000 e s.m.i. ; • l’art. 42 comma 3 lettera C del D.P.R. 16 dicembre 1992 n. 495 ; CONSIDERATO: • che con nota pervenuta in data 17/03/2021 con prot. 10690 l’Impresa appaltatrice DAPAM SRL. ha formalizzato richiesta di cantierizzazione per l’esecuzione della posa di barriere stradali di sicurezza lungo la SP. 14; • che i lavori sulla strada in oggetto interesseranno una corsia della piattaforma stradale; PRESO ATTO: • che l’esecuzione dei lavori, richiede l’istituzione di un senso unico alternato regolato da impianto semaforico di cantiere; RISCONTRATA: • la necessità di dar seguito alla richiesta dell’Impresa DAPAM S.r.l., in ordine ai lavori in oggetto, al segnalamento dell’area di cantiere e all’apposizione del divieto di sosta in area di cantiere; ORDINA per motivi d’incolumità pubblica ed esigenze di carattere tecnico, lungo la S.P. -

Comune Di Ferrera Di Varese Documento Di Piano Relazione

Comune di Ferrera di Varese - Piano di Governo del Territorio DOCUMENTO DI PIANO - Relazione modificata a seguito accoglimento osservazioni piano adottato dicembre 2009 COMUNE DI FERRERA DI VARESE DOCUMENTO DI PIANO RELAZIONE INDICE GENERALE STUDIO BRUSA PASQUE’ – VARESE prima parte 1 Comune di Ferrera di Varese - Piano di Governo del Territorio DOCUMENTO DI PIANO - Relazione modificata a seguito accoglimento osservazioni piano adottato dicembre 2009 PRIMA PARTE ........................................................................................................................... 6 1 INTRODUZIONE ..................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Il quadro normativo ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Partecipazione al processo di pianificazione.............................................................................. 7 2 PROCEDURA E SCHEMA DI PROCESSO INTEGRATO PGT-VAS ................................................. 7 3 ELENCO DEGLI ELABORATI DEL PGT .................................................................................... 10 4 IL QUADRO RICOGNITIVO ECONOMICO-SOCIALE ............................................................... 12 4.1 Struttura demografica e inquadramento socioeconomico.......................................................... 12 4.1.1 La collocazione del Comune nel contesto geografico ed individuazione dell’area di indagine ........ 12 4.1.2 Aspetti