Oral History of Adele Goldberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early History of Smalltalk

The Early History of Smalltalk http://www.accesscom.com/~darius/EarlyHistoryS... The Early History of Smalltalk Alan C. Kay Apple Computer [email protected]# Permission to copy without fee all or part of this material is granted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for direct commercial advantage, the ACM copyright notice and the title of the publication and its date appear, and notice is given that copying is by permission of the Association for Computing Machinery. To copy otherwise, or to republish, requires a fee and/or specific permission. HOPL-II/4/93/MA, USA © 1993 ACM 0-89791-571-2/93/0004/0069...$1.50 Abstract Most ideas come from previous ideas. The sixties, particularly in the ARPA community, gave rise to a host of notions about "human-computer symbiosis" through interactive time-shared computers, graphics screens and pointing devices. Advanced computer languages were invented to simulate complex systems such as oil refineries and semi-intelligent behavior. The soon-to- follow paradigm shift of modern personal computing, overlapping window interfaces, and object-oriented design came from seeing the work of the sixties as something more than a "better old thing." This is, more than a better way: to do mainframe computing; for end-users to invoke functionality; to make data structures more abstract. Instead the promise of exponential growth in computing/$/volume demanded that the sixties be regarded as "almost a new thing" and to find out what the actual "new things" might be. For example, one would compute with a handheld "Dynabook" in a way that would not be possible on a shared mainframe; millions of potential users meant that the user interface would have to become a learning environment along the lines of Montessori and Bruner; and needs for large scope, reduction in complexity, and end-user literacy would require that data and control structures be done away with in favor of a more biological scheme of protected universal cells interacting only through messages that could mimic any desired behavior. -

Smahtalk Kernel Language Fv1anual

This document is for Xerox internal use only SmaHtalk Kernel Language fv1anual BY Larry Tesler SEPTEMBER 1977 Smalltalk is a programming rang'uage that deals with objects. Every object has its own data. Objects communicate by sending and receiving messages according to simple. protocols. Objects are grouped into classes. The objects of a class are called its instances. Each class specifies the protocols its instances will know as well as the methods they will use to respond to messages they receive.· The standard facilities of the Small talk system include i/o protocols for disk, display, keyboard, mouse, and Ethernet; basic data structures such as numbers, strings, arrays, and dictionaries; basic control structures such as loops and processes; program editing, compiling, and debugging; text editing, illustration, music. animation, and information storage and retrieval. Smalltalk applications include education, personal computing, and systems research. This interim reference manual covers the semantics and the present syntax of the Smalltalk kernel language. It is assumed that the reader has seen Smalltalk in operation and has programmed computers in Algol-like languages. Familiarity with LISP, Simula, and/or Smallta!k-72 should be helpful but is not necessary. System operation is described in the memo, Browsing and Error Analysis, available under separate cover from the Learning Research Group, Systems Science Laboratory. XEROX PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER 3333 Coyote Hill Road / Palo J\lto / California 94304 This document is for Xerox internal use only Discla inler The Smalltalk kernel system is not yet ready for general release. \Ve ask that you do not copy and distribute either the manual or the system at this time. -

Hopscotch: Towards User Interface Composition Vassili Bykov Cadence Design Systems, 2655 Seely Ave, San Jose, CA 95134

Hopscotch: Towards User Interface Composition Vassili Bykov Cadence Design Systems, 2655 Seely Ave, San Jose, CA 95134 Abstract Hopscotch is the application framework and development environment of Newspeak, a new programming language and platform inspired by Smalltalk, Self and Beta. Hopscotch avoids a number of design limitations and shortcomings of traditional UIs and UI frameworks by favoring an interaction model and implementing a framework architecture that enable composition of interfaces. This paper discusses the deficiencies of the traditional approach, provides an overview of the Hopscotch alternative and analyses how it improves upon the status quo. 1. Introduction Hopscotch are attributable to its revised interaction and navigation model as much as to the underlying Newspeak [1] is a programming language and framework architecture. For this reason, this paper platform being developed by a team led by Gilad pays equal attention to the compositional frame- Bracha at Cadence Design Systems, Inc. The sys- work architecture and to the changes in the inter- tem is currently hosted inside Squeak [2], a descen- action model of Hopscotch compared to more tradi- dent of Smalltalk-80 [3]. Smalltalk, along with Self tional development environments. [4] and Beta [5], is also among the most important influences on the design of the Newspeak language. 2. Traditional Interface Construction This paper focuses on Hopscotch, the applica- tion framework of Newspeak and the Newspeak The art of devising forms to be filled in depends IDE implemented concurrently with the frame- on three elements: obscurity, lack of space, and work. The framework and the IDE allow easy nav- the heaviest penalties for failure. -

Automatic Graph Drawing Lecture 15 Early HCI @Apple/Xerox

Inf-GraphDraw: Automatic Graph Drawing Lecture 15 Early HCI @Apple/Xerox Reinhard von Hanxleden [email protected] 1 [Wikipedia] • One of the first highly successful mass- produced microcomputer products • 5–6 millions produced from 1977 to 1993 • Designed to look like a home appliance • It’s success caused IBM to build the PC • Influenced by Breakout • Visicalc, earliest spreadsheet, first ran on Apple IIe 1981: Xerox Star • Officially named Xerox 8010 Information System • First commercial system to incorporate various technologies that have since become standard in personal computers: • Bitmapped display, window-based graphical user interface • Icons, folders, mouse (two-button) • Ethernet networking, file servers, print servers, and e- mail. • Sold with software based on Lisp (early functional/AI language) and Smalltalk (early OO language) [Wikipedia, Fair Use] Xerox Star Evolution of “Document” Icon Shape [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0] 1983: Apple Lisa [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 2.0 fr] Apple Lisa • One of the first personal computers with a graphical user interface (GUI) • In 1982, Steve Jobs (Cofounder of Apple, with Steve Wozniak) was forced out of Lisa project, moved on into existing Macintosh project, and redefined Mac as cheaper, more usable version of Lisa • Lisa was challenged by relatively high price, insufficient SW library, unreliable floppy disks, and immediate release of Macintosh • Sold just about 10,000 units in two years • Introduced several advanced features that would not reappear on Mac or PC for many years Lisa Office -

Interview with James Mitchell

Interview with James Mitchell Interviewed by: David C. Brock Recorded February 19, 2019 Santa Barbara, CA CHM Reference number: X8963.2019 © 2019 Computer History Museum Interview with James Mitchell Brock: Yeah. So, yeah, maybe we can talk about your transition from Carnegie Mellon to PARC and how that opportunity came about, and what your thinking was about joining the new lab. Mitchell: I basically finished my PhD and left in July of 1970. I had missed graduation that year, so my diploma says 1971. But, in fact, I'd been out working for a year by then, and at PARC, you know, there were a number of other grad students I knew, and two of them had gone to work for a start-up in Berkeley that-- there were two Berkeley computer science departments, and the engineering one left to form this company called Berkeley Computer Corporation with Mel Pirtle running it and Butler Lampson kind of a chief technical officer and Chuck Thacker and so on, and anyway the people that I-- the two other grad students that had gone already that I knew, when I was going out, I was starting to go around and interview in early 1970 because I knew I was close to being finished, and it was in those days because there were so few people who had PhDs in computer science and every university was trying to build a department, and industrial research places like Bell Labs were trying to hire people and so on, anywhere you went with a new PhD you got an offer. -

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

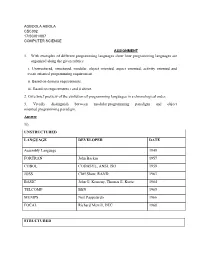

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

A Ccnversational Extensible System for the Animation of Shaded Images(*)

A CCNVERSATIONAL EXTENSIBLE SYSTEM FOR THE ANIMATION OF SHADED IMAGES(*) by Ronald M. Baecker Dynamic Graphics Project, Computer Systems Research Group University of Torcnto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Abstract The terms "conversational" and "extensible" are defined and shown to be useful properties of computer animation systems. A conversational extensible system for the animation of shaded images is then described. With this system, implemented on a minicomputer, the animator can sketch images and movements freehand, or can define them algorithmically via the Smalltalk language. The system is itself implemented in Smalltalk, and hence can be easily extended or mcdified to suit the animator's personal style. (*) This work was supported primarily by the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. I. Introduction We shall now focus upon the second category cf systems. The strengths of GENESYS lay in the spontaneous, real time Computer animation consists of a interaction it facilitated, and in the variety cf techniques and processes in ccnceptualization of the computer animated which the computer is used as an aid in the film and the filmmaking process that it production of animated sequences [Halas 74, embodied. The heart of this Wein 74]. Computer animation systems can conceptualization was a duality between generally be classified as either image and movement, and a rich set of algorihmic or demonstrative [Tilson 75]. representations for movement and tools for the construction of movement. The ARTA and 1. Programming-language based systems Eurtnyk-Wein systems demonstrated the (Algorithmic systems) utility of various picture construction and transformation tools, including the ability EEFLIX [Knowlton 64], EXFLOR [Knowlton to interpolate between images (key frame 7C], and ZAPP (Guerin 73, Eaecker 76], animation). -

Silicon Valley Inventor of 'Cut, Copy and Paste' Dies 20 February 2020

Silicon Valley inventor of 'cut, copy and paste' dies 20 February 2020 cutting portions of printed text and affixing them elsewhere with adhesive. "Tesler created the idea of 'cut, copy, & paste' and combined computer science training with a counterculture vision that computers should be for everyone," the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley tweeted Wednesday. The command was made popular by Apple after being incorporated in software on the Lisa computer in 1983 and the original Macintosh that debuted the next year. Tesler worked for Apple in 1980 after being Lawrence "Larry" Tesler, who invented the "cut, copy recruited away from Xerox by late co-founder Steve and paste" command, died on Monday Jobs. Tesler spent 17 years at Apple, rising to chief scientist. Silicon Valley on Wednesday was mourning a pioneering computer scientist whose He went on to establish an education startup and accomplishments included inventing the widely do stints in user-experience technology at Amazon relied on "cut, copy and paste" command. and Yahoo. Bronx-born Lawrence "Larry" Tesler died this week © 2020 AFP at age 74, according to Xerox, where he spent part of his career. "The inventor of cut/copy & paste, find & replace, and more was former Xerox researcher Larry Tesler," the company tweeted. "Your workday is easier thanks to his revolutionary ideas. Larry passed away Monday, so please join us in celebrating him." A graduate of Stanford University, Tesler specialized in human–computer interaction, employing his skills at Amazon, Apple, Yahoo, and the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). The cut and paste command was reportedly inspired by old time editing that involved actually 1 / 2 APA citation: Silicon Valley inventor of 'cut, copy and paste' dies (2020, February 20) retrieved 28 September 2021 from https://techxplore.com/news/2020-02-silicon-valley-inventor-dies.html This document is subject to copyright. -

Sunday April 25, 2021 Reinventing Business, Liberty and Rights, Sex and Drugs in NYC, Xerox PARC and Bell Labs Michael Hiltzik

What Happens Next – Sunday April 25, 2021 Reinventing Business, Liberty and Rights, Sex and Drugs in NYC, Xerox PARC and Bell Labs Michael Hiltzik Larry Bernstein: In the meantime, we're going to segue to something completely different, which is the industrial lab. I'm going to start with my Mike Hiltzik who'll speak for six minutes, and then to be followed by Jon Gertner. Mike is going to talk about his book, Dealers of Lightning: Xerox Park and the Dawn of the Computer Age. Mike, go ahead. Michael Hiltzik: The question that Larry asked me to answer, which was, how did Xerox blow it? Meaning, how did it miss the opportunities that it was given by the brilliant scientists and engineers and hired for its Palo Alto Research Center, I think, perhaps isn't exactly the right question to ask about PARC. The right question, it seems to me should be: Did Xerox blow it? The answer requires some nuance. If you think that Xerox should have exploited PARC's invention of the Alto, the first personal computer, by launching the personal computer market, then you'll think the answer is yes. But if you think Xerox never made any money from PARC, which is sort of the received wisdom, the answer is no. PARC invented the laser printer and Xerox made a ton of money from that technology alone. If you think Xerox blew it because it was in the perfect position to exploit PARC's invention, not only the Alto, but ethernet, and the graphical user interface, and the perfected use of the mouse, the answer is still no. -

15 Years Ago in BYTE BYTE.Com Write to BYTE.Com Advertise with August 1996 / Blasts from the Past / 15 Years Ago in BYTE BYTE.Com

BYTE.com Page 1 of 20 Archives Columns Jump to... Features Print Archives 1994-1998 HOME ABOUT US ARCHIVES CONTACT US ADVERTISE REGISTER Special BYTE Digest Michael Abrash's Graphics Programming Black Book 101 Perl Articles About Us How to Access 15 Years Ago in BYTE BYTE.com Write to BYTE.com Advertise with August 1996 / Blasts From The Past / 15 Years Ago in BYTE BYTE.com Newsletter Are languages being used according to their Free E-mail original design? Larry Tesler of Apple thought Newsletter from they should be....ideally. BYTE.com your email here BYTE devoted almost the entire issue to Smalltalk, Smalltalk-80, and other object-oriented-programming topics. In one article, Apple's Larr Subscribe Tesler said, "You can write almost any program better in a language you know well than in one you know poorly. But if languages are compared from a viewpoint broader than that of a narrow expert, each language stands out above the others when used for the purpose for which it was designed." Hold that thought. August 1981 's almost-exclusive coverage of Smalltalk provided a wealth of information from programming and debugging, to the graphics kernel. Here's what else Larry Tesler had to say: The Smalltalk Environment by Larry Tesler [Editor's Note: Due to the large volume of graphics originally included with this article, you will need to refer to the print issue, page 90, to view them.] As I write this article, I am wearing a T-shirt given to me by a friend. http://www.byte.com/art/9608/sec4/art3.htm 5/14/2006 BYTE.com Page 2 of 20 Emblazoned across the chest is the loud plea: DON'T MODE ME IN Surrounding the caption is a ring of barbed wire that symbolizes the trapped feeling I often experience when my computer is "in a mode." In small print around the shirt are the names of some modes I have known and deplored since the early 1960s when I came out of the darkness of punched cards into the dawn of interactive terminals. -

Apple Lisa Computer Commentary Larry Tesler • 28 November 2000

Apple Lisa Computer Commentary Larry Tesler • 28 November 2000 Source http://www.techtv.com/screensavers/print/0,23102,3013380,00.html 10 July 2003 Tales from Tessler: History of the Lisa Computer Larry Tesler, former Xerox PARC researcher and Apple chief scientist, explains the impact of the Lisa, a computer ahead of its time. By Larry Tesler, CEO Stagecast Apple introduced the revolutionary Lisa computer in 1983, but only about 30,000 were sold. The product was overpriced and slow. It also entered the market on the heels of the popular Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet, which established the IBM PC as the standard in business. But this didn't stop the Lisa from pointing the way to the future of personal computing. Why was the Lisa slow? Because it didn't have enough power to run the demanding graphical user interface. Here's how it compares to my G4 Cube: Even that low-power setup was too expensive to compete with an MS-DOS PC, which had a quarter of the memory and an 8-bit microprocessor. What Survives from Apple's Lisa? Although Lisa came and went almost in the blink of an eye, many of its features are still found in today's Windows PCs and Macintosh computers. Lisa's Pioneering Features • A menu bar with pull-down menus and identified keyboard shortcuts • File menu commands named New, Open, Close, Save, Save as, and Print • Windows and icons moved by pointing, clicking, and dragging • Dialog boxes with radio buttons, check boxes, and OK/Cancel buttons • Alert boxes to provide warnings and explain errors Lisa innovations incorporated into the -

Notetaker System Manual

This document is for Xerox internal use only DRAFT - DRAFT - DRAFT - DRAFT NoteTaker System Manual BY Douglas G. Fairbairn December 1978 SSL-78-1xxx ABSTRACT This manual describes the NoteTaker computing system. The NoteTaker is a portable computer of considerable power useful for a wide range of computational and simulation oriented functions. XEROX PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER 3333 Coyote Hill Road / Palo Alto / California 94304 This document is for Xerox internal use only DRAFT ~ DRAFT - DRAFT· DRAFT NoteTaker System Manual - DRAFT - DRAFT - January 18,1979 12:48 PMDecember 10, 2 1978 12:24 PM PREFACE The NoteTaker is a very powerful portable computer intended for a wide variety of applications. Its intended users are "children of all ages": five-year-olds and high school students, as well as writers, researchers, artists, managers, and engineers. NoteTaker offers the capability of a general-purpose minicomputer, and allows it to be used without even plugging it into an AC power outlet. This manual describes the hardware components of the system in three levels of detail. The intioduction summarizes the main features of the NoteTaker hardware. Section 2 gives an overview of the architecture. Section 3 offers the detail required to program the system and to interface other devices to it. The NoteTaker has its roots in the long-time desire of the Learning Research Group at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC) to have a portable system on which to experiment with its ideas concerning personal computers. The architecture of the machine was defined by Douglas Fairbairn of .the LSI Systems Area at PARC in conjunction with LRG.