Apple Confidential 2.0 the Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apple & Deloitte Team up to Accelerate Business

NEWS RELEASE Apple & Deloitte Team Up to Accelerate Business Transformation on iPhone & iPad 9/28/2016 Deloitte Introduces New Apple Practice to Help Businesses Design & Implement iPhone & iPad Solutions CUPERTINO, Calif. & NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Apple® and Deloitte today announced a partnership to help companies quickly and easily transform the way they work by maximizing the power, ease-of-use and security the iOS platform brings to the workplace through iPhone® and iPad®. As part of the joint effort, Deloitte is creating a first-of-its-kind Apple practice with over 5,000 strategic advisors who are solely focused on helping businesses change the way they work across their entire enterprise, from customer-facing functions such as retail, field services and recruiting, to R&D, inventory management and back-office systems. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160928006317/en/ Apple CEO Tim Cook and Deloitte Global CEO Punit Renjen meet at Apple's campus to Apple and Deloitte will also announce a joint effort to accelerate business transformation using iOS, iPhone & iPad. collaborate on the development (Courtesy of Apple/Roy Zipstein) of a new service offering from Deloitte Consulting called EnterpriseNext, designed to help clients fully take advantage of the iOS ecosystem of hardware, software and services in the workplace. The new offering will help customers discover the highest impact possibilities within their industries and quickly develop custom solutions through rapid prototyping. 1 “We know that iOS is the best mobile platform for business because we’ve experienced the benefit ourselves with over 100,000 iOS devices in use by Deloitte’s workforce, running 75 custom apps,” said Punit Renjen, CEO of Deloitte Global. -

Broken Breakout Promises

Broken Breakout Promises Broken Breakout Promises Before co-founding Apple in April 1976, Steve Jobs was one of the To make ends meet in the summer of first 50 employees at Atari, the legendary Silicon Valley game company 1972, Woz, Jobs, and Jobs’ girlfriend took $3-per-hour jobs at the Westgate founded by Nolan Kay Bushnell in 1972. Atari’s Pong, a simple Mall in San Jose, California, dressing up electronic version of ping-pong, had caught on like wildfire in arcades as Alice In Wonderland characters. Jobs and homes across the country, and Bushnell was anxious to come up and Woz alternated as the White Rabbit with a successor. He envisioned a variation on Pong called Breakout, and the Mad Hatter. in which the player bounced a ball off a paddle at the bottom of the screen in an attempt to smash the bricks in a wall at the top. Bushnell turned to Jobs, a technician, to design the circuitry. Initially Jobs tried to do the work himself, but soon realized he was in way over his head and asked his friend Steve Wozniak to bail him out. “Steve wasn’t capable of designing anything that complex. He came .atarihq.com) “He was the only person I met who knew more about electronics than me.” Courtesy of Atari Gaming Headquarters (www Courtesy of Steve Jobs, explaining his initial fascination with Woz “Steve didn’t know very much about electronics.” Conceived by Bushnell, Breakout was originally designed by Wozniak and Jobs. Steve Wozniak For more info, or to order a copy, please visit http://www.netcom.com/~owenink/confidential.html 17 Broken Breakout Promises to me and said Atari would like a game and described how it would work,” recalls Wozniak. -

The Role of Ansel in Tracy Letts' Killer Joe: a Production Thesis in Acting

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The oler of Ansel in Tracy Letts' Killer Joe: a production thesis in acting Ronald William Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Ronald William, "The or le of Ansel in Tracy Letts' Killer Joe: a production thesis in acting" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 3197. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF ANSEL IN TRACY LETTS’ KILLER JOE: A PRODUCTION THESIS IN ACTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Ronald William Smith B.S., Clemson University, 2000 May 2003 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my professors, Bob and Annmarie Davis, Jo Curtis Lester, Nick Erickson and John Dennis for their knowledge, dedication, and care. I would like to thank my classmates: Deb, you are a friend and I’ve learned so much from your experiences. Fire, don’t ever lose the passion you have for life and art, it is beautiful and contagious. -

Apple Kicks Off Event; $1,000 Iphone Is Expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke and Barbara Ortutay

Apple kicks off event; $1,000 iPhone is expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke And Barbara Ortutay on him with joy instead of sadness." The souped-up "anniversary" iPhone, which would come a decade after Jobs unveiled the first version, could also cost twice what the original iPhone did. It would set a new price threshold for any smartphone intended to appeal to a mass market. WHAT A THOUSAND BUCKS WILL BUY Apple CEO Tim Cook kicks off the event for a new product announcement at the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) Apple has kicked off a September product event at which it is expected to unveil a dramatically redesigned iPhone that could cost $1,000. With a photo of former Apple co-founder and CEO Steve It's the first product event Apple is holding at its Jobs projected in the background, Apple CEO Tim Cook new spaceship-like headquarters in Cupertino, kicks off the event for a new product announcement at California. Before getting to the new iPhone, the the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus, company unveiled a new Apple Watch model with Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP cellular service and an updated version of its Apple Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) TV streaming device. The event opened in a darkened auditorium, with only the audience's phones gleaming like stars, Various leaks have indicated the new phone will along with a message that said "Welcome to Steve feature a sharper display, a so-called OLED screen Jobs Theater." A voiceover from Jobs, Apple's co- that will extend from edge to edge of the device, founder who died in 2011, opened the event before thus eliminating the exterior gap, or "bezel," that CEO Tim Cook took stage. -

Adopting the Aqua Interface

INSIDE MAC OS X Adopting the Aqua Interface Updated for Mac OS X Public Beta Release. 9/8/00 © Apple Computer, Inc. 2000 Apple Computer, Inc. Even though Apple has reviewed this © 2000 Apple Computer, Inc. manual, APPLE MAKES NO All rights reserved. WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, WITH No part of this publication may be RESPECT TO THIS MANUAL, ITS reproduced, stored in a retrieval QUALITY, ACCURACY, system, or transmitted, in any form or MERCHANTABILITY, OR FITNESS by any means, mechanical, electronic, FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. AS A photocopying, recording, or RESULT, THIS MANUAL IS SOLD “AS otherwise, without prior written IS,” AND YOU, THE PURCHASER, ARE permission of Apple Computer, Inc., ASSUMING THE ENTIRE RISK AS TO with the following exceptions: Any ITS QUALITY AND ACCURACY. person is hereby authorized to store documentation on a single computer IN NO EVENT WILL APPLE BE LIABLE for personal use only and to print FOR DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, copies of documentation for personal INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL use provided that the documentation DAMAGES RESULTING FROM ANY contains Apple’s copyright notice. DEFECT OR INACCURACY IN THIS The Apple logo is a trademark of MANUAL, even if advised of the Apple Computer, Inc. possibility of such damages. Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo THE WARRANTY AND REMEDIES SET (Option-Shift-K) for commercial FORTH ABOVE ARE EXCLUSIVE AND purposes without the prior written IN LIEU OF ALL OTHERS, ORAL OR consent of Apple may constitute WRITTEN, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. No trademark infringement and unfair Apple dealer, agent, or employee is competition in violation of federal authorized to make any modification, and state laws. -

A Brief History of GNOME

A Brief History of GNOME Jonathan Blandford <[email protected]> July 29, 2017 MANCHESTER, UK 2 A Brief History of GNOME 2 Setting the Stage 1984 - 1997 A Brief History of GNOME 3 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT ● ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto Early graphics system for ● 1991 — GNU General Public License v2.0 Unix systems ● 1991 — Initial Linux release ● Created by MIT ● 1991 — Era of big projects ● Focused on mechanism, ● 1993 — Distributions appear not policy ● 1995 — Windows 95 released ● Holy Moly! X11 is almost ● 1995 — The GIMP released 35 years old ● 1996 — KDE Announced A Brief History of GNOME 4 twm circa 1995 ● Network Transparency ● Window Managers ● Netscape Navigator ● Toolkits (aw, motif) ● Simple apps ● Virtual Desktops / Workspaces A Brief History of GNOME 5 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto ● Founded by Richard Stallman ● ● 1991 — GNU General Public License v2.0 Our fundamental Freedoms: ○ Freedom to run ● 1991 — Initial Linux release ○ Freedom to study ● 1991 — Era of big projects ○ Freedom to redistribute ○ Freedom to modify and ● 1993 — Distributions appear improve ● 1995 — Windows 95 released ● Also, a set of compilers, ● 1995 — The GIMP released userspace tools, editors, etc. ● 1996 — KDE Announced This was an overtly political movement and act A Brief History of GNOME 6 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT “The licenses for most software are ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto designed to take away your freedom to ● 1991 — GNU General Public License share and change it. By contrast, the v2.0 GNU General Public License is intended to guarantee your freedom to share and ● 1991 — Initial Linux release change free software--to make sure the ● 1991 — Era of big projects software is free for all its users. -

SYSTEM SOFTWARE, MEMORY, and RESOURCES Includes Demonstration Program Sysmemres

1 SYSTEM SOFTWARE, MEMORY, AND RESOURCES Includes Demonstration Program SysMemRes Macintosh System Software All Macintosh applications make many calls, for many purposes, to Macintosh system software functions. Such purposes include, for example, the creation of standard user interface elements such as windows and menus, the drawing of text and graphics, and the coordination of the application's actions with other open applications.1 The majority of system software functions are components of either the Macintosh Toolbox or the Macintosh Operating System. In essence: • Toolbox functions have to do with mediating your application with the user. They relate, in general, to the management of elements of the user interface. • Operating System functions have to do with mediating your application with the Macintosh hardware, performing such basic low-level tasks as file input and output, memory management and process and device control. Managers The entire collection of system software functions is further divided into functional groups which are usually known as managers.2 Toolbox The main Toolbox managers are as follows: QUICKDRAW WINDOW MANAGER DIALOG MANAGER CONTROL MANAGER MENU MANAGER TEXTEDIT EVENT MANAGER RESOURCE HELP MANAGER SCRAP MANAGER FINDER INTERFACE LIST MANAGER MANAGER SOUND MANAGER SOUND INPUT STANDARD FILE NAVIGATION APPEARANCE FOLDER MANAGER PACKAGE SERVICES MANAGER MANAGER Introduced with Mac OS 8.0. Note that Navigation Services renders Standard File Package obsolescent 1 The main other open application that an application needs to work with is the Finder, which is responsible for keeping track of files and managing the user’s desktop. The Finder is not really part of the system software, although it is sometimes difficult to tell where the Finder ends and the system software begins. -

Mastering Amiga AMOS to Phil South ISBN: 1-873308-19-1 Revised Edition: May 1993 (Previously Published October 1992 Under ISBN: 1-873308-12-4)

Applicable to all Amigas Easy and Powerful Programming Hands-on Tuturial and Guide 1 . I Bruce Smith Books astering Amiga A OS Revised Edition Phil South Bruce Smith Books Mastering Amiga AMOS to Phil South ISBN: 1-873308-19-1 Revised Edition: May 1993 (Previously published October 1992 under ISBN: 1-873308-12-4) Editor: Mark Webb Typesetting: Bruce Smith Books Limited All Trademarks and Registered Trademarks used are hereby acknowledged. E&OE All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or translated in any form, by any means, mechanical, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this publication (and any programs and software associated with it) is correct and accurate, the Publisher cannot accept liability for any consequential loss or damage, however caused, arising as a result of using the information printed herein. Bruce Smith Books is an imprint of Bruce Smith Books Limited. Published by: Bruce Smith Books Limited, PO Box 382, St. Albans, Herts, AL2 3JD. Telephone: (0923) 894355 — Fax: (0923) 894366. Registered in England No. 2695164. Registered Office: 51 Quarry Street, Guildford, Surrey, GU1 3UA. Printed and bound in the UK by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport. The Author Phil South is a writer and journalist, who started writing for a living in 1984, when he realised he couldn’t actually stand working for anyone but himself. He says his popular columns in magazines such as Computer Shopper, Amiga Format and Amiga Computing are much harder to write than they are to read. -

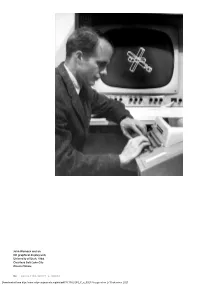

Downloaded for Storage and Display—As Is Common with Contemporary Systems—Because in 1952 There Were No Image File Formats to Capture the Graphical Output of a Screen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The random-access image: Memory and the history of the computer screen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0b3873pn Journal Grey Room, 70(70) ISSN 1526-3819 Author Gaboury, J Publication Date 2018-03-01 DOI 10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. -

Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick?

AALTO UNIVERSITY School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Markku Reunanen Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Licentiate Thesis Helsinki, April 23, 2010 Supervisor: Professor Tapio Takala AALTO UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT OF LICENTIATE THESIS School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Author Date Markku Reunanen April 23, 2010 Pages 134 Title of thesis Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Professorship Professorship code Contents Production T013Z Supervisor Professor Tapio Takala Instructor - This licentiate thesis deals with a worldwide community of hobbyists called the demoscene. The activities of the community in question revolve around real-time multimedia demonstrations known as demos. The historical frame of the study spans from the late 1970s, and the advent of affordable home computers, up to 2009. So far little academic research has been conducted on the topic and the number of other publications is almost equally low. The work done by other researchers is discussed and additional connections are made to other related fields of study such as computer history and media research. The material of the study consists principally of demos, contemporary disk magazines and online sources such as community websites and archives. A general overview of the demoscene and its practices is provided to the reader as a foundation for understanding the more in-depth topics. One chapter is dedicated to the analysis of the artifacts produced by the community and another to the discussion of the computer hardware in relation to the creative aspirations of the community members. -

The Candy Maker's Guide by Fletcher Manufacturing Company

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Candy Maker's Guide, by Fletcher Manufacturing Company This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Candy Maker's Guide A Collection of Choice Recipes for Sugar Boiling Author: Fletcher Manufacturing Company Release Date: October 20, 2009 [EBook #30293] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CANDY MAKER'S GUIDE *** Produced by Meredith Bach, Rose Acquavella, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.) THE CANDY MAKER'S GUIDE A COLLECTION OF CHOICE RECIPES FOR SUGAR BOILING COMPILED AND PUBLISHED BY THE FLETCHER MNF'G. CO. MANUFACTURERS OF Confectioners' and Candy Makers' Tools and Machines TEA AND COFFEE URNS BAKERS' CONFECTIONERS AND HOTEL SUPPLIES IMPORTERS AND DEALERS IN PURE FRUIT JUICES, FLAVORING EXTRACTS, FRUIT OILS, ESSENTIAL OILS, MALT EXTRACT, XXXX GLUCOSE, ETC. Prize Medal and Diploma awarded at Toronto Industrial Exhibition 1894, for General Excellence in Style and Finish of our goods. 440-442 YONGE ST.,—TORONTO, CAN. TORONTO J JOHNSTON PRINTER & STATIONER 105 CHURCH ST 1896 FLETCHER MNF'G. CO. TORONTO. Manufacturers and dealers in Generators, Steel and Copper Soda Water Cylinders, Soda Founts, Tumbler Washers, Freezers, Ice Breaking Machines, Ice Cream Refrigerators, Milk Shakers, Ice Shaves, Lemon Squeezers, Ice Cream Cans, Packing Tubs, Flavoring Extracts, Golden and Crystal Flake for making Ice Cream, Ice Cream Bricks and Forms, and every article necessary for Soda Water and Ice Cream business. -

Hereby the Screen Stands in For, and Thereby Occludes, the Deeper Workings of the Computer Itself

John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00233 by guest on 27 September 2021 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. 4 But the computer screen was also a cathode ray tube (CRT) phosphorescing in response to an electron beam, modified by a grid of randomly accessible memory that stores, maps, and transforms thousands of bits in real time. The screen is not simply an enduring technique or evocative metaphor; it is a hardware object whose transformations have shaped the ma - terial conditions of our visual culture.