Our Landscape Concerns Us All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Asbestos

The asbestos lie The past and present of an industrial catastrophe — Maria Roselli Maria Roselli, is an investigative journalist for asbestos issues, migration, and economic development. Born in Italy, raised and living in Zurich, Switzerland, Roselli has written frequently in German, Italian, and French media on asbestos use. Contributing authors: Laurent Vogel is researcher at the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI), which is based in Brussels, Belgium. ETUI is the independent research and training centre of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), which is the umbrella organisation of the European trade unions. Dr Barry Castleman, author of Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, now in its fifth edition, has frequently been called as an expert witness both for plaintiffs and defendants; he has also testified before the U.S. Congress on asbestos use in the United States. He lives in Garrett Park, Maryland. Laurie Kazan-Allen is the editor of the British Asbestos Newsletter and the Coordinator of the International Ban Asbestos Secretariat. She is based in London. Kathleen Ruff is the founder and coordinator of the organisation Right On Canada of the Rideau Institute to promote citizen action for advocating for human rights in Canadian government policies. In 2011, she was named Canadian Public Health Association’s National Public Health Hero for ‘revealing the inaccuracies in the propaganda that the asbestos industry has employed for the better part of the last century to mislead citizens about the seriousness of the threat of asbestos -

Behörden Der Kirchen

BEHÖRDEN DER KIRCHEN Evangelisch-Reformierte Landeskirche Synode Büro Präsident Hefti Andreas, lic. iur., Glarus Vizepräsidentin Lienhard Marianne, Landesstatthalter, Elm Aktuar Paysen-Petersen Jacqueline, Rufi 1. Stimmenzähler Hefti Hansheinrich, Schwanden 2. Stimmenzäler Wachsmuth Michael, Mitlödi Im Amt stehende Pfarrer und Pfarrerinnen Jahrgang Amtsantritt Neumann Almut, Mitlödi (Provisorin) 1952 1992 Rhyner-Funk Andrea, Elm (Pfarramt für Behinderte) 1965 2006 Brüll Beck Christina, Mollis 1972 2008 Doll Dagmar, Glarus 1973 2009 Doll Sebastian, Glarus 1972 2009 Hofmann Peter, Ennenda 1966 2011 Lustenberger Iris, Ennenda 1967 2011 Peters Matthias, Niederurnen 1958 2011 Zubler Daniel (Spitalpfarramt), Glarus 1961 2012 Aerni Edi, Netstal 1959 2014 Schneider Christoph, Betschwanden 1968 2015 Wüthrich Beat Emanuel, Matt 1958 2016 Pfiffner Annemarie, Obstalden 1963 2017 Wyler-Eschle Bruno, Bilten (Provisor) Von den Kirchgemeinden gewählte 50 Abgeordnete Bilten-Schänis Jud-Baumann Brigit, Schänis Paysen-Petersen Jacqueline, Rufi Baumgartner-Dürst Lukrezia, Bilten Kerenzen Schaub Walter, Obstalden Kamm-Menzi Marianne, Filzbach 78 Behörden der Kirchen Niederurnen Knöpfel Heini, Niederurnen Stuck Hans Markus, Niederurnen Fischli Elisabeth, Niederurnen Etter David, Niederurnen Hämmerli Christian, Niederurnen Mollis-Näfels Nöthiger-Lutz Markus, Mollis Schmid Brunner Ernst, Mollis Guler Verena, Mollis Perdrizat-Schweizer René, Mollis Kälin-Zimmermann Ruth, Mollis Senn Heidi, Mollis Netstal Cremonese-Feichtinger Andrea, Netstal Häuptli Saarah, Netstal -

35. Glarner Stadtlauf 2019, Glarus (173)

Datum: 01.11.19 35. Glarner Stadtlauf 2019, Glarus Zeit: 08:55:45 Seite: 1 (173) Schulklassen 3 Rang Teamname Klassierte Schnitt netto Diff zu 8.44,7 Name und Vorname Land/Ort Zeit Stnr 1. Engi Primarschule 5./6. Kl. 6 8:46.5 1.8 Bäbler Nevio Engi 7.55,2 1001 Frick Sven Elm 7.56,3 1003 Tschudi Sales Matt 8.16,2 1007 Blumer Anja Engi 8.45,0 1002 Lissner Emelie Engi 9.44,5 1004 Lüthi Flurina Engi 10.02,0 1005 2. Niederurnen Linth Escher Kl. 5c 13 8:38.8 5.9 Schmid Sheila Niederurnen 6.38,3 1451 Moos Noël Niederurnen 6.41,1 1445 Gübeli Lyra Niederurnen 7.04,2 1438 Menzi Matias Niederurnen 7.14,4 1444 Feusi Sonja Niederurnen 7.36,1 1436 Kovacevic Imran Niederurnen 8.22,4 1441 Maris Luisa-Maria Bilten 8.51,2 1443 Thoma Manuel Niederurnen 9.11,1 1452 Lazic Maria Ziegelbrücke 9.13,2 1442 Fontana Seraina Niederurnen 10.14,5 1437 Prenka Alexander Niederurnen 10.17,4 1447 Popadic Andjela Niederurnen 10.29,1 1446 Rrahmanaj Bleart Niederurnen 10.32,3 1448 3. Netstal Primarschule 5./6. Kl. 13 8:30.4 14.3 Correia Mariana Coutinho Netstal 7.01,6 1092 Fernandes Afonso Da Cunha Netstal 7.11,4 1093 Islami Venis Netstal 7.20,0 1094 Malacarne Moira Netstal 7.38,8 1098 Stombellini Lorenzo Netstal 7.55,5 1102 Sahinovic Aldin Netstal 8.08,8 1101 Ajeti Endrita Netstal 8.46,1 1089 Rodrigues Kevin Netstal 8.48,3 1100 Konuk Latife Netstal 9.15,4 1097 Kelmedi Blerijana Netstal 9.19,3 1096 Ramadani Diana Netstal 9.34,9 1099 Jenni Mark Netstal 9.47,7 1095 Barco Ruben Netstal 9.48,2 1091 4. -

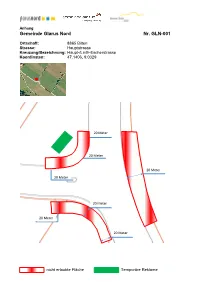

Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-001

Anhang Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-001 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Hauptstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Haupt-/Linth-Escherstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1406, 9.0329 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-002 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Linth-Escherstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Höhe SmartMarkt Koordinaten: 47.1493, 9.0323 5 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-003 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Landstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Land-/Niederrietstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1602, 9.0026 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-004 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Badstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: gegenüber Schiesstand Koordinaten: 47.1319, 9.0480 5 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-005 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Ziegelbrückstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Wiese römisch-katholische Kirche Koordinaten: 47.1276, 9.0554 3 Meter Aussenkante Trottoir nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-006 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Hauptstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Hauptstrasse / Gerbiweg Koordinaten: 47.1211, 9.0544 3 Meter Aussenkante Trottoir B a nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-007 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Eternitstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Haupt-/Eternitstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1199, 9.0581 5 Meter 20 Meter 10 Meter 20 Meter ab Aussenradius 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. -

Bahnhof Ennenda 13 Dezember 2020 - 11 Dezember 2021

Abfahrt Départ - Partenza - Departure Bahnhof Ennenda 13 Dezember 2020 - 11 Dezember 2021 4 00 13 00 22 00 4 47 S25 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 13 09 S25 Zürich HB via Glarus–Netstal– 22 17 S6 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach 13 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi 22 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– 5 00 13 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 5 09 S25 Zürich HB via Glarus–Netstal– 13 47 S25 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 23 00 Ziegelbrücke–Pfäffikon SZ Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach 5 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi 23 17 S6 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 5 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– 14 00 Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 23 39 S6 Ziegelbrücke via Glarus–Netstal– 5 47 S25 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 14 09 S25 Zürich HB via Glarus–Netstal– Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 14 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi 0 00 6 00 14 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 0 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi 6 09 S25 Zürich HB via Glarus–Netstal– 14 47 S25 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 0 39 S6 Ziegelbrücke via Glarus–Netstal– Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 6 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi 6 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– 15 00 1 00 Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen 6 47 S25 Linthal via Mitlödi–Schwanden GL– 15 09 S25 Zürich HB via Glarus–Netstal– 1 56 736 Linthal, Bahnhof via Nidfurn-Haslen–Leuggelbach Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Mitlödi, Hauptstrasse– 15 17 S6 Schwanden GL via Mitlödi Schwanden GL, Hauptstrasse– 7 00 15 39 S6 Rapperswil SG via Glarus–Netstal– Schwanden GL, Spittel– Näfels-Mollis–Nieder- und Oberurnen Nidfurn, Abzw. -

Recycling-Kalender 2021

Öffnungszeiten Sammelstellen Abfuhrplan Bilten Fallen Strassensammlungen mit Feiertagen zusammen, so werden die Abfälle am nächsten offiziellen Sammeltag abgeführt. Werkhof Sägenstrasse 11 Dienstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr Donnerstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr Sammeldaten Kehricht / Sperrgut Verkaufsstellen Sperrgutmarken Samstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr ausgenommen Fest- und Feiertage Bereitstellung ab 07.00 Uhr Bilten Denner Satellit, Hauptstrasse 8 Niederurnen Werkhof Bahnhofstrasse 1 Bilten Montag und Donnerstag Niederurnen Apollo, Brugghof 7 Montag 13.00 – 14.00 Uhr Drogerie Singer, Ziegelbrückstrasse 7 Dienstag 13.00 – 14.00 Uhr Niederurnen Dienstag und Freitag Welldro AG, Ziegelbrückstrasse 19 Recycling-Kalender 2021 Mittwoch 13.00 – 14.00 Uhr, 18.00 – 19.00 Uhr Post, Ziegelbrückstrasse 21 Donnerstag 13.00 – 14.00 Uhr Oberurnen Montag und Donnerstag Freitag 13.00 – 14.00 Uhr Oberurnen Louis Müller, Poststrasse 30 Samstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr ausgenommen Fest- und Feiertage Näfels Dienstag und Freitag Näfels Elektroshop, im Dorf 17 Oberurnen Mollis Dienstag und Freitag Post, Bahnhofstrasse 5 Landstrasse 20a Dienstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr Filzbach Mittwoch Mollis Hager, Spar Supermarkt, Bahnhofstrasse 4 Donnerstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr Samstag 09.30 – 11.00 Uhr ausgenommen Fest- und Feiertage Obstalden Mittwoch Filzbach Winmärt, Lebensmittel, Kerenzerbergstrasse 28 Näfels Mühlehorn Mittwoch Obstalden Dorfladen, Kerenzerbergstrasse 25 Werkhof Burgstrasse 17 Montag 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr Dienstag 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr Sammeldaten Grünabfälle Sammeldaten Papiersammlungen Mittwoch 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr, 18.00 – 19.00 Uhr Donnerstag 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr Bereitstellung ab 07.00 Uhr – wie für Hauskehrichtabfuhren Bilten Freitag 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr Die Termine werden im Glarus Nord Anzeiger und auf der Homepage Mittwoch 20. -

Rangliste J+S Skirennen 2017

Rangliste J+S Skirennen 2017 Rang Nr. Name Vorname Jg. Wohnort Club / Schule Zeit Knaben Kategorie 1 2011/2012 1 5 Gallati Giordano 2011 Netstal 47.81 2 4 Herger Michael 2011 Urnerboden 50.49 Mädchen Kategorie 2 2009/2010 1 9 Bösch Nuria 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 33.02 2 8 Rhyner Amanda 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 33.47 3 7 Luchsinger Michaela 2009 Engi 2. Klasse, Engi 33.77 4 10 Nigg Lorena 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 35.51 5 11 Drijfholt Sophie 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 36.93 6 13 Knecht Liv 2009 Glarus Primar Riedern 36.94 7 12 Bernet Rebecca 2009 Elm 1. Klasse Engi 37.94 Knaben Kategorie 2 2009/2010 1 20 Grünenfelder Milo 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 31.92 2 19 Marty Cyril 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 31.99 3 22 Beglinger Corvin 2009 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 32.29 4 18 Marti Mattia 2009 Schwanden 1. Klasse 34.32 5 21 Zentner Mattia 2009 Schwändi Schulhaus Schwändi 35.77 6 16 Elmer Marco 2009 Elm 1. Klasse Engi 36.66 7 27 Beglinger Jaron 2010 Mollis Schulhaus Dorf 38.26 8 25 Paulz Aaron 2010 Schwanden Kindergarten 38.59 9 24 Disch Ruedi 2010 Schwändi Schulhaus Schwändi 39.76 10 17 Spörri Jamie 2009 Glarus 39.91 11 26 Herger Ueli 2010 Urnerboden 47.41 . Mädchen Kategorie 3 2007/2008 1 30 Gehrig Bianca 2007 Mollis Schule am Bach 31.21 2 43 Abächerli Antonia 2008 Näfels Dorfschulhaus Näfels 31.85 3 45 Bernet Julia 2008 Elm 3. Klasse Engi 31.86 4 32 Bartels Rena 2007 Mollis Schulhaus Rauti Oberurnen 32.91 5 38 Iten Ladina 2007 Mollis Schule am Bach 33.49 6 31 Maggiacomo Ilenia 2007 Oberurnen Schulhaus Rauti Oberurnen 34.35 7 34 Laager Lya Sophie 2007 Mollis Schulhaus Rauti Oberurnen 34.39 8 35 Nigg Seraina 2007 Mollis Schule am Bach 35.17 9 44 Honold Paula 2008 Näfels 2. -

Welcome to the Canton of Glarus Inhaltsverzeichnis Table of Contents

Englisch Welcome to the canton of Glarus Inhaltsverzeichnis Table of contents 1 Willkommen Welcome 4 2 Integration Integration 6 3 Aufenthaltsbewilligung und Residence permit and 8 Integrationsvereinbarung integration agreement 4 Rechte und Pflichten Rights and obligations 10 5 Arbeit Work 12 6 Deutsch lernen Learning German 16 7 Kinderbetreuung und Child care and education 18 Vorschulerziehung of pre-school children 8 Schule School 20 9 Aus- und Weiterbildung Basic and further training 24 10 Wohnen & Alltag: gut zu wissen Living & everyday life: good to know 26 1 1 Umwelt- Abfallentsorgung Environment - Waste disposal 28 1 2 Gesundheit- Health- 30 Krankenpflegeversicherung medical care insurance 13 Soziale Sicherheit Social security 34 1 4 Freizeit - Begegnung Leisure - Interaction 36 1 5 Kultur Culture 38 1 6 Mobilität Mobility 40 1 7 Die Schweiz Switzerland 42 1 8 Der Kanton Glarus The canton of Glarus 46 1 9 Adressen & Links Addresses & Links 48 Willkommen Welcome 1 1 Liebe Neuzuzügerinnen und Neuzuzüger Dear New Residents Wir heissen Sie herzlich willkommen. Es freut uns, dass Sie sich entschieden We wish you a warm welcome. We are delighted that you have decided to live haben in unserem Kanton zu wohnen. in our canton. Der Kanton Glarus bietet seinen Bewohnerinnen und Bewohnern in einer wun- The canton of Glarus, with its beautiful scenery, offers its inhabitants attractive derschönen Landschaft attraktive Arbeits- und Wohnangebote. Für Interess- working and living choices. Various events are held all year round for culture ierte finden das ganze Jahr über verschiedene kulturelle Anlässe statt. Für Frei- lovers. Numerous associations, sports facilities, winter and summers sports zeitaktivitäten stehen zahlreiche Vereine, Sportanlagen, Winter- und Sommer- activities are available. -

736 Ziegelbrücke - Linthal Stand: 25

FAHRPLANJAHR 2021 736 Ziegelbrücke - Linthal Stand: 25. November 2020 S25 S6 736 S25 S6 736 S25 S6 S25 S6 S25 20511 11609 701 20515 11613 703 20519 11617 20523 11621 20527 SBB SOB AS SBB SOB AS SBB SOB SBB SOB SBB [Rapperswil Rapperswil Zürich HB Rapperswil Zürich HB SG] SG SG Rapperswil SG ab 05 33 06 33 07 33 Ziegelbrücke an 05 56 06 56 07 56 Chur ab 05 16 06 16 07 16 Ziegelbrücke an 06 00 07 00 08 00 Zürich HB ab 06 12 06 43 07 12 07 43 Ziegelbrücke an 06 58 07 25 07 58 08 25 Ziegelbrücke 04 30 05 00 05 30 06 03 06 30 07 03 07 30 08 03 08 30 Nieder- und Oberurnen 04 32 05 02 05 32 06 05 06 32 07 05 07 32 08 05 08 32 Näfels-Mollis 04 36 05 05 05 36 06 07 06 36 07 07 07 36 08 07 08 36 Netstal 04 39 05 09 05 39 06 10 06 39 07 10 07 39 08 10 08 39 Glarus 04 46 05 16 05 46 06 16 06 46 07 16 07 46 08 16 08 46 Ennenda 04 47 05 17 05 47 06 17 06 47 07 17 07 47 08 17 08 47 Mitlödi 04 50 05 20 05 50 06 20 06 50 07 20 07 50 08 20 08 50 Schwanden GL 04 54 05 24 05 54 06 24 06 54 07 24 07 54 08 24 08 54 Schwanden GL 04 59 05 29 05 59 06 29 06 59 07 59 08 59 Nidfurn-Haslen 05 01 05 33 06 01 06 33 07 01 08 01 09 01 Leuggelbach 05 03 05 38 06 03 06 38 07 03 08 03 09 03 Luchsingen-Hätzingen 05 05 05 40 06 05 06 40 07 05 08 05 09 05 Diesbach-Betschwanden 05 08 05 43 06 08 06 43 07 08 08 08 09 08 Rüti GL 05 10 05 47 06 10 06 47 07 10 08 10 09 10 Linthal Braunwaldbahn 05 13 05 51 06 13 06 51 07 13 08 13 09 13 Linthal 05 16 05 53 06 16 06 53 07 16 08 16 09 16 S6 S25 S6 S25 S6 S25 S6 S25 S6 S25 S6 11625 20531 11629 20535 11633 20539 11637 20543 11641 20547 -

SEBA Gene Conservation Units (EUFORGEN) Proposal for Selction of Candidate Gene Conservation Units (GCU) for Scattered Broadleav

SEBA Gene conservation units (EUFORGEN) page 1 / 2 Proposal for selction of candidate gene conservation units (GCU) for scattered broadleaves in Switzerland attrib Record ID Entry Latin species name Bewertu Notes on qualification Type of Canton Region Municipality Forest Provenance Notes on location Notes on Type of ex situ National Notes on juristic Longitude Latitude Digita Altitude Main river River last levelTotal area Total area Year(s) of Number Average Genotype Average number Average Share in Type of marker(s) Notes on ute Numb ng pot. population Region responsable Conservation Registration aspects X coordinate Y coordinate lizatio (m) tributary stand (ha) region establish of number s of trees (nr/ha) number of total basal genetic er GCU 1 structure partners Unit Number n of (ha) ment genotype of ramets originate trees (nr/ha) area (%) information Phase in situ GIS s per from ## ID_rec ID_id ID_nr ID_spec_name QU_pro QU_note LO_pop_typ LO_kt LO_reg LO_muni LO_for LO_prov LO_note LO_partner_not JU_exSitu_type JU_nat_nr JU_note SI_lon_X SI_lon_Y SI_di SI_alt SI_river_mai SI_river_lastl ST_stand ST_regio ST_date ST_geno ST_rame ST_regio ST_spec_dens ST_spec_d ST_spec_s GE_markers_type GE_note 603 IN-ACEPL-CHE-03 3 Acer platanoides 1 high regional density, population size C region GL Nordalpen Region Glarner Unterland (5 0 Swiss Northern 0 0 0 0 0 728000 219500 (Y) 420- Rhein Linth, Limmat 0 78 km2 0000 10'000 >2 >1 - 0 and quality (SEBA1) due to the Gemeinden): Bilten, Niederunren, Alps 1000 influence of Foehn (warm and dry wind Oberurnen, -

Glarner Burgen

Glarner Burgen Autor(en): Kamm, Rolf Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Mittelalter : Zeitschrift des Schweizerischen Burgenvereins = Moyen Age : revue de l'Association Suisse Châteaux Forts = Medioevo : rivista dell'Associazione Svizzera dei Castelli = Temp medieval : revista da l'Associaziun Svizra da Chastels Band (Jahr): 15 (2010) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-166634 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch "t/. m Glarner Burgen von Rolf Kamm Einleitung NIEDER WINDEGG Das Glarnerland weist einige, wenn auch recht unspektakuläre mittelalterliche Mauerreste auf. In Niederurnen, OBERWINDEGG / >- o MÜU f[ bei Schwanden HttoemiftNEN Oberurnen, Netstal, Mitlödi (eher Sool) und dV scheint kleine ihre hrmmI] es Burgen gegeben zu haben, / BEGLINGEN, LETZI Überreste sind zum Teil noch gut sichtbar. -

Glarus Nord – Ihre Gemeinde. Nützliche Links

Glarus Nord – Ihre Gemeinde. Nützliche Links www.glarus-nord.ch www.fridolin.ch www.glarusnord-tourismus.ch www.guidle.com www.glarus.ch Raumreservationen: www.glarus-nord.ch www.glarus24.ch Tageskarten GA: www.glarus-nord.ch www.suedostschweiz.ch Die Gemeinde Glarus Nord Diese Broschüre Die 3 Standorte Seite 4 – 9 enthält QR-Codes Ein QR-Code führt auf Präsidiales 10 – 15 spezifische themenver- bundene Seiten im Internet. Dazu benötigt Bildung 16 – 19 man einen QR-Scanner, der auf dem Smartphone entweder standardmässig Bau und Umwelt 20 / 21 installiert ist oder gratis heruntergeladen werden kann. Die QR-Codes in Liegenschaften 22 / 23 dieser Broschüre führen direkt auf die ent- Wald und 24 / 25 sprechenden Seiten und Landwirtschaft Unterlagen auf der Homepage der Gemeinde Gesundheit, 26 – 29 Glarus Nord. Jugend und Kultur Sicherheit 30 / 31 Technische Betriebe 32 – 35 Alters- und Pflegeheime 36 / 37 URL SCAN www.glarus-nord.ch OPEN 1 Die Gemeinde Glarus Nord ZÜRICH Mühlehorn Bilten Walensee Mühlehorn Obstalden Weesen Filzbach Bilten CHUR Glarnerland r n e r e r u e d g N i i r ä l e T Niederurnen b r Talalpsee e z Oberurnen n e r i t a l e ä n d K h w S c Näfels Mollis M u l l e r n t a l e e r s e b l p O Obersee n a r o F GLARUS 2 ZÜRICH Mühlehorn Bilten Walensee Mühlehorn Obstalden Filzbach Bilten CHUR Glarnerland r n e r e r u e d g N i i r ä l e T Niederurnen b r Talalpsee e z Oberurnen n e r i t a l e Einwohner 17 700 n d K w ä Fläche 14 698 ha c h S Näfels Mollis Landwirtschaftliche Nutzfläche 5 572 ha M Wald 5 773 ha u l l e r n t a l e e r s e b l p O Obersee n a r o F GLARUS 3 Die 3 Standorte Niederurnen Postadresse Gemeinde Glarus Nord Postfach 268 8867 Niederurnen Standort Gemeindehaus Schulstrasse 2 8867 Niederurnen Fax 058 611 70 50 Sprechstunde Gemeindepräsident (ohne Voranmeldung) Schule Bilten Jeden ersten Montag im Monat Ziegelbrückestrasse 14.00 – 19.00 Uhr P Rest.