The Asbestos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vereine Kanton Glarus

Telefon 055 646 62 46 E-Mail: [email protected] www.gl.ch Bildung und Kultur Integration Stand: 11.06.2021 Gerichtshausstrasse 25 8750 Glarus Vereine Kanton Glarus Sport/Freizeitaktivitäten Verein / Anbieter Adresse Kontaktperson Ort Tel. / E-Mail Beschrieb Aikido Glarus Zinggenstrasse 2 Hansjörg Weber Mollis 078 660 05 66 Japanische Kampfkunst Badminton Club Glarus Platte 28 Dirk Sewing Ennenda 055 640 69 53 Badminton spielen Blauring Näfels Autschachen 1 Fränzi Fischli Näfels 079 373 77 66 Verschiedene Niederurnen Fronalpstrasse 21 Sibylle Bodenmann Niederurnen 055 610 18 64 Freizeitbetätigungen für Kinder. Christlicher Glaube. Seite 1 Fussballclub Glarus Adlerguet 19a Renato Micheroli Glarus 055 640 88 17 Fussball Fussballclub Linth 04 Erich Fischli Näfels 079 693 53 22 Fussballclub Netstal Schlöffeli 16 Moor Raphaël Netstal 079 244 10 11 Fussballclub Rüti GL Dorfstrasse 90 Roger Nievergelt Rüti 079 332 76 01 Fussballclub Schwanden Bahnhofstrasse 31 René Schätti Schwanden 079 575 31 61 Rythmische Gymnastik Speerstrasse 13 Stephanie Blunschi Näfels 079 596 94 12 Turnen & Gymnastik https://www.gltv.ch/rg Glaronia Volleyballclub Lurigenstrasse 17 Peter Aebli Glarus 055 640 37 24 Volleyball Judoclub Yawara Glarnerland Fabrikstrasse 3 Claudio Nicoletti Niederurnen 055 640 31 35 Judo Seite 2 Karateschule Glarus Landstrasse 41 / Daniel Rimann Glarus 055 650 19 30 Karate / Kickboxen Zaunturnhalle 079 421 14 06 KiTu-Kinderturnen Hätzingen- Turnhalle Hätzingen Elsbeth Mächler Hätzingen 079 695 87 66 Turnen / Gymnastik Luchsingen Leichtathletikverein Glarus Bifang 1 Reto Menzi Filzbach 079 787 80 45 Turnen / Gymnastik www.lavglarus.ch MuKi Hätzingen-Luchsingen Sonnenhof Liz Schindler Leuggelbach 076 436 2313 Turnen für Mütter/Väter mit MuKi-Turnen Bilten Hauptstrasse 58a Ruth Marti Bilten 055 610 21 54 Kind von 3-5 J. -

Glarussüd Anzeiger

GZA/PP • 8867 Niederurnen VONROTZAG PETER Vorhänge Bodenbeläge InnendekorationParkett GlarusSüd Anzeiger Teppiche GLARNER WOCHE Nr.49Freitag,4.Dezember 2009 Regionalzeitung für Mitlödi, Schwändi, Sool, Schwanden, Haslen, Nidfurn, Leuggelbach, www.glarnerwoche.ch Luchsingen, Hätzingen, Diesbach, Betschwanden, Rüti, Braunwald, Linthal, Engi, Matt und Elm» ■ INTEGRATION 5 Das Integrationsprojekt «Glarus Süd sind wir» nimmt Formen an. Höhepunkt wird das gemeinsame Schulabschlussfest am 1. Juli. ■ UMFRAGE 7 Vor dem Fernseher, im Bett oder auf dem Liegestuhl – dort erholen sich die befragten Personen aus dem Glarnerland am liebsten. ■ PERSÖNLICH 9 Die lachenden Kinderaugen freuen dem Samichlaus auch in Glarus Süd am meisten. ■ RATGEBER 20 Der Umgang mit alten Hunden braucht Geduld, Einfühlungsver- mögen und Verständnis. ■ VERLOSUNG 21 Mitmachen und gewinnen. «Samichlaus» Hanspeter Klauser, der Glarner Kindern eine Tiergeschichte erzählt. Bild Werner Beerli ■ GLARUS SÜD 22 Die Gemeindeversammlungen von Luchsingen und Schwändi tagten. Vom Heiligen zum Werbeträger Der Samichlaus, ursprünglich Bilten, Näfels, Glarus und bringer ist ja bei jedem Wetter ein Heiliger aus dem Orient, ist Schwanden nahmen Hunderte willkommen. Mit einem zurzeit bei uns allgegenwärtig. Menschen mit Fackeln und Lam- Inserat in Im roten Mantel, die Zipfel- pionen an der «Schellnete» teil Klauser machts seit 25 Jahren der Glarner mütze über dem Kopf und wal- und bereiteten dem liebenswer- In den nächsten Wochen werden Woche kann lendem Bart fasziniert er die ten Mann auf seinem Weg ins Tal auch die Glarner Samichläuse von Kinder stets aufs Neue. Über hinunter einen herzlichen Emp- Haus zu Haus ziehen und die Kin- nichts schief die Jahrhunderte hat er sich fang. der beschenken. Einer von ihnen gehen. stark gewandelt. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Behörden Der Kirchen

BEHÖRDEN DER KIRCHEN Evangelisch-Reformierte Landeskirche Synode Büro Präsident Hefti Andreas, lic. iur., Glarus Vizepräsidentin Lienhard Marianne, Landesstatthalter, Elm Aktuar Paysen-Petersen Jacqueline, Rufi 1. Stimmenzähler Hefti Hansheinrich, Schwanden 2. Stimmenzäler Wachsmuth Michael, Mitlödi Im Amt stehende Pfarrer und Pfarrerinnen Jahrgang Amtsantritt Neumann Almut, Mitlödi (Provisorin) 1952 1992 Rhyner-Funk Andrea, Elm (Pfarramt für Behinderte) 1965 2006 Brüll Beck Christina, Mollis 1972 2008 Doll Dagmar, Glarus 1973 2009 Doll Sebastian, Glarus 1972 2009 Hofmann Peter, Ennenda 1966 2011 Lustenberger Iris, Ennenda 1967 2011 Peters Matthias, Niederurnen 1958 2011 Zubler Daniel (Spitalpfarramt), Glarus 1961 2012 Aerni Edi, Netstal 1959 2014 Schneider Christoph, Betschwanden 1968 2015 Wüthrich Beat Emanuel, Matt 1958 2016 Pfiffner Annemarie, Obstalden 1963 2017 Wyler-Eschle Bruno, Bilten (Provisor) Von den Kirchgemeinden gewählte 50 Abgeordnete Bilten-Schänis Jud-Baumann Brigit, Schänis Paysen-Petersen Jacqueline, Rufi Baumgartner-Dürst Lukrezia, Bilten Kerenzen Schaub Walter, Obstalden Kamm-Menzi Marianne, Filzbach 78 Behörden der Kirchen Niederurnen Knöpfel Heini, Niederurnen Stuck Hans Markus, Niederurnen Fischli Elisabeth, Niederurnen Etter David, Niederurnen Hämmerli Christian, Niederurnen Mollis-Näfels Nöthiger-Lutz Markus, Mollis Schmid Brunner Ernst, Mollis Guler Verena, Mollis Perdrizat-Schweizer René, Mollis Kälin-Zimmermann Ruth, Mollis Senn Heidi, Mollis Netstal Cremonese-Feichtinger Andrea, Netstal Häuptli Saarah, Netstal -

35. Glarner Stadtlauf 2019, Glarus (173)

Datum: 01.11.19 35. Glarner Stadtlauf 2019, Glarus Zeit: 08:55:45 Seite: 1 (173) Schulklassen 3 Rang Teamname Klassierte Schnitt netto Diff zu 8.44,7 Name und Vorname Land/Ort Zeit Stnr 1. Engi Primarschule 5./6. Kl. 6 8:46.5 1.8 Bäbler Nevio Engi 7.55,2 1001 Frick Sven Elm 7.56,3 1003 Tschudi Sales Matt 8.16,2 1007 Blumer Anja Engi 8.45,0 1002 Lissner Emelie Engi 9.44,5 1004 Lüthi Flurina Engi 10.02,0 1005 2. Niederurnen Linth Escher Kl. 5c 13 8:38.8 5.9 Schmid Sheila Niederurnen 6.38,3 1451 Moos Noël Niederurnen 6.41,1 1445 Gübeli Lyra Niederurnen 7.04,2 1438 Menzi Matias Niederurnen 7.14,4 1444 Feusi Sonja Niederurnen 7.36,1 1436 Kovacevic Imran Niederurnen 8.22,4 1441 Maris Luisa-Maria Bilten 8.51,2 1443 Thoma Manuel Niederurnen 9.11,1 1452 Lazic Maria Ziegelbrücke 9.13,2 1442 Fontana Seraina Niederurnen 10.14,5 1437 Prenka Alexander Niederurnen 10.17,4 1447 Popadic Andjela Niederurnen 10.29,1 1446 Rrahmanaj Bleart Niederurnen 10.32,3 1448 3. Netstal Primarschule 5./6. Kl. 13 8:30.4 14.3 Correia Mariana Coutinho Netstal 7.01,6 1092 Fernandes Afonso Da Cunha Netstal 7.11,4 1093 Islami Venis Netstal 7.20,0 1094 Malacarne Moira Netstal 7.38,8 1098 Stombellini Lorenzo Netstal 7.55,5 1102 Sahinovic Aldin Netstal 8.08,8 1101 Ajeti Endrita Netstal 8.46,1 1089 Rodrigues Kevin Netstal 8.48,3 1100 Konuk Latife Netstal 9.15,4 1097 Kelmedi Blerijana Netstal 9.19,3 1096 Ramadani Diana Netstal 9.34,9 1099 Jenni Mark Netstal 9.47,7 1095 Barco Ruben Netstal 9.48,2 1091 4. -

Ergänzung Des Maßnahmenprogramms 2016 Bis 2021Für Den Bayerischen Anteil Am Flussgebiet Rhein− Zusatzmaßnahmen Gemäß §

Ergänzung des Maßnahmenprogramms 2016 bis 2021 für den bayerischen Anteil am Flussgebiet Rhein − Zusatzmaßnahmen gemäß § 82 Abs. 5 WHG – (Programmergänzung für die Periode 2019 bis 2021) Infolge der Ergebnisse vertiefender Untersuchungen und Kontrollen zum Gewässerzustand in Bayern fand im Jahr 2018 eine Überprüfung des Maßnahmenprogramms für das bayerische Rheingebiet für den Bewirtschaftungszeitraum 2016 bis 2021 statt. Im Ergebnis dieser Überprüfung zeigte sich ein Bedarf an zusätzlichen Maßnahmen zur Reduzierung von Phosphoreinträgen in Oberflächengewässer durch Nachrüstung von Kläranlagen, um die Bewirtschaftungsziele gemäß §§ 27 bis 31 WHG fristgerecht zu erreichen. Die erforderlichen Maßnahmen sollen noch im zweiten Bewirtschaftungszeitraum bis 2021 umgesetzt werden. Gemäß § 82 Abs. 5 WHG werden daher diese Maßnahmen als nachträglich erforderliche Zusatzmaßnahmen in das Maßnahmenprogramm aufgenommen und in nachfolgender Liste in analoger Weise wie die ergänzenden Maßnahmen Planungseinheit- und Wasserkörper- bezogen und mit Bezug auf den in Deutschland gültigen LAWA-BLANO-Maßnahmenkatalog aufgeführt. Liste von Zusatzmaßnahmen für Oberflächenwasserkörper im bayerischen Einzugsgebiet des Rheins Oberer Main Weißer Main, Roter Main – OMN_PE01 Wasserkörper Geplante Maßnahmen Kennzahl Name Kennzahl Bezeichnung (gemäß LAWA- bzw. Bayern-Maßnahmenkatalog) 2_F084 Weißer Main bis Einmündung der Ölschnitz 3 Ausbau kommunaler Kläranlagen zur Reduzierung der Phosphoreinträge Nebengewässer Weißer Main: Ölschnitz, Kronach (zum Weißen Main), Trebgast -

Belgian Week of Gastroenterology 2019 Belgian Association for The

Belgian Week of Gastroenterology 2019 http://www.bwge.be Belgian Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL) / Belgian Liver Intestine Committee (BLIC) A01 The sPDGFR-beta containing PRTA-score is a novel diagnostic algorithm for significant liver fibrosis in patients with viral, alcoholic, and metabolic liver disease J. LAMBRECHT (1), S. VERHULST (1), I. MANNAERTS (1), J. SOWA (2), J. BEST (2), A. CANBAY (2), H. REYNAERT (1), L. VAN GRUNSVEN (1) / [1] Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Jette, Belgium, Department of Basic Biomedical Sciences, Liver Cell Biology Laboratory, [2] University Hospital Magdeburg, , Germany, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Infectious Diseases Introduction: Diagnosis of liver fibrosis onset and regression remains a controversial subject in the current clinical setting, as the gold standard remains the invasive liver biopsy. Multiple novel non-invasive markers have been proposed but lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of early stage liver fibrosis. Platelet Derived Growth Factor Receptor beta (PDGFRβ) has been associated to hepatic stellate cell activation and has been the target of multiple therapeutic studies. However, little is known concerning its use as a diagnostic agent. Aim: In this study, we analysed the diagnostic potential of PDGFRβ for liver fibrosis in a heterogenous patient population. Methods: The study cohort consisted of 148 patients with liver fibrosis/cirrhosis due to various causes of liver injury (metabolic, alcoholic, viral), and 14 healthy individuals as control population. A validation cohort of 57 patients with metabolic liver disease, who underwent liver biopsy to stage fibrosis, were gathered. Circulating soluble PDGFRβ (sPDGFRβ) levels were determined using a commercial ELISA kit. -

The History of the Russian Revolution

The History of the Russian Revolution Leon Trotsky Volume Three Contents Notes on the Text i 1 THE PEASANTRY BEFORE OCTOBER 1 2 THE PROBLEM OF NATIONALITIES 25 3 WITHDRAWAL FROM THE PRE -PARLIAMENT AND STRUGGLE FOR THE SOVIET CONGRESS 46 4 THE MILITARY-REVOLUTIONARY COMMITTEE 66 5 LENIN SUMMONS TO INSURRECTION 93 6 THE ART OF INSURRECTION 125 7 THE CONQUEST OF THE CAPITAL 149 8 THE CAPTURE OF THE WINTER PALACE 178 9 THE OCTOBER INSURRECTION 205 10 THE CONGRESS OF THE SOVIET DICTATORSHIP 224 11 CONCLUSION 255 NOTE TO THE APPENDICES (AND APPENDIX NO. 1) 260 2 3 CONTENTS SOCIALISM IN A SEPARATE COUNTRY 283 HISTORIC REFERENCES ON THE THEORY OF “PERMANENT REVOLU- TION” 319 4 CONTENTS Notes on the Text The History of the Russian Revolution Volume Two Leon Trotsky First published: 1930 This edition: 2000 by Chris Russell for Marxists Internet Archive Please note: The text may make reference to page numbers within this document. These page numbers were maintained during the transcription process to remain faithful to the original edition and not this version and, therefore, are likely to be inaccurate. This statement applies only to the text itself and not any indices or tables of contents which have been reproduced for this edition. i ii Notes on the Text CHAPTER 1 THE PEASANTRY BEFORE OCTOBER Civilization has made the peasantry its pack animal. The bourgeoisie in the long run only changed the form of the pack. Barely tolerated on the threshold of the national life, the peasant stands essentially outside the threshold of science. -

Achterbahn Im Naturpark Hassberge

Naturpark-Runden im Bamberger Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Auflösung. Norden (3): Achterbahn im Naturpark Hassberge Entfernung: ca. 63 km, Dauer: ca. 1 Tag Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Auflösung. Vorwort Vom Sofa direkt in den Sattel? Ein lässiger Radtag sieht anders aus und ein paar Trainingsrunden sollte man schon absolviert haben, bevor man diese Tour angeht. Auf beinahe 1.000 m Bergund Talfahrt Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer hält sie einige Höhenflüge bereit. Sie ist zugleich Herausforderung und Auflösung. Stand: 8.9.2017 Elixier für Körper, Geist und Seele. Denn die imposanten Burgruinen, schmucken Schlösser und Orte sind ein Augenschmaus und die Panoramen ohne Ende. Die Tour verläuft im Baunachtal großenteils auf der Trasse des alten Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Maro-Express und stellt kaum An sprü che an die Kondition. So richtig Auflösung. steil wirds erst vor Altenstein, hinter Pfaffendorf und vor Leuzendorf. Über Bischwind in einer lange Schleife hinauf zur Ruine Bramberg. Weiteres Ab und Auf bis Jesserndorf, dann die finale lange Stei gung nach Bühl. Oben folgen wir zeitweise dem Rennweg. Schließ lich ab nach Rudendorf ins Tal der Lauter, die uns nach Baunach begleitet. Weg be schrei bung Wir benutzen fast nur Rad-, Feld und Waldwege sowie wenig Start punkt ist am Bahn hof Ebern. Wir steigen aus dem Zug und befahrene Nebenstraßen und sind meist mitten in der Natur. lenken gleich links vor zum Bahnübergang. Da rechts in die Georg- Eine Spezialmarkierung gibt es nicht, aber das allgemeine Radweg- Nadler-Straße und weiter in der Häfnergasse bis zur Vorfahrtsstraße. -

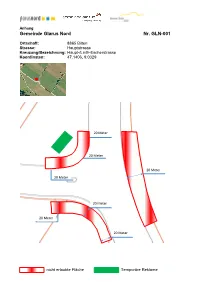

Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-001

Anhang Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-001 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Hauptstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Haupt-/Linth-Escherstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1406, 9.0329 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-002 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Linth-Escherstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Höhe SmartMarkt Koordinaten: 47.1493, 9.0323 5 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-003 Ortschaft: 8865 Bilten Strasse: Landstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Land-/Niederrietstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1602, 9.0026 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-004 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Badstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: gegenüber Schiesstand Koordinaten: 47.1319, 9.0480 5 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-005 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Ziegelbrückstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Wiese römisch-katholische Kirche Koordinaten: 47.1276, 9.0554 3 Meter Aussenkante Trottoir nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-006 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Hauptstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Hauptstrasse / Gerbiweg Koordinaten: 47.1211, 9.0544 3 Meter Aussenkante Trottoir B a nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. Nr.: 33.03 / Seite 2/2 Gemeinde Glarus Nord Nr. GLN-007 Ortschaft: 8867 Niederurnen Strasse: Eternitstrasse Kreuzung/Bezeichnung: Haupt-/Eternitstrasse Koordinaten: 47.1199, 9.0581 5 Meter 20 Meter 10 Meter 20 Meter ab Aussenradius 20 Meter nicht erlaubte Fläche Temporäre Reklame Reg. -

Architecture and Nation. the Schleswig Example, in Comparison to Other European Border Regions

In Situ Revue des patrimoines 38 | 2019 Architecture et patrimoine des frontières. Entre identités nationales et héritage partagé Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 DOI: 10.4000/insitu.21149 ISSN: 1630-7305 Publisher Ministère de la culture Electronic reference Peter Dragsbo, « Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions », In Situ [En ligne], 38 | 2019, mis en ligne le 11 mars 2019, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 ; DOI : 10.4000/insitu.21149 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. In Situ Revues des patrimoines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other Europe... 1 Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo 1 This contribution to the anthology is the result of a research work, carried out in 2013-14 as part of the research program at Museum Sønderjylland – Sønderborg Castle, the museum for Danish-German history in the Schleswig/ Slesvig border region. Inspired by long-term investigations into the cultural encounters and mixtures of the Danish-German border region, I wanted to widen the perspective and make a comparison between the application of architecture in a series of border regions, in which national affiliation, identity and power have shifted through history. The focus was mainly directed towards the old German border regions, whose nationality changed in the wave of World War I: Alsace (Elsaβ), Lorraine (Lothringen) and the western parts of Poland (former provinces of Posen and Westpreussen). -

Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

6/26 Silver Age Extravaganza: Marvel, DC, Dell, & More! 6/26/2021 This session will broadcast LIVE via ProxiBid.com at 6 PM on 6/26/21! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 16 Dennis The Menace Silver Age Comic Lot 1 Lot of (4) Hallden/Fawcett comics. #43, 47, 74, and 87. VG-/VG 2 Amazing Spider-Man #3/1st Dr. Octopus! 1 First appearance and origin of Dr. Octopus. VG- condition. condition. 3 Tales to Astonish #100 1 17 Challengers of the Unknown #13/22/27 1 Classic battle the Hulk vs the Sub-Mariner. VF/VF+ with offset DC Silver Age. VG to FN- range. binding and bad staple placement. 18 Challengers of the Unknown #34/35/48 1 DC Silver Age. VG-/VG condition. 4 Tales to Astonish #98 1 Incredible Adkins and Rosen undersea cover. VF- condition. 19 Challengers of the Unknown #49/50/53/61 1 DC Silver Age. VG+/FN condition. 5 Tales to Astonish #97 1 Hulk smash collaborative cover by Marie Severin, Dan Adkins, and 20 Flash Gordon King/Charlton Comics Lot 1 Artie Simek. FN+/ VF- with bad staple placement. 6 comics. #3-5, and #8 from King Comics and #12 and 13 from Charlton. VG+ to FN+ range. 6 Tales to Astonish #95/Semi-Key 1 First appearance of Walter Newell (becomes Stingray).