Mark Twain Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut

MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS No. CT-359-A (Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF THE MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS NO. CT-359-A Location: Rear of 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut. USGS Hartford North Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates; 18.691050.4626060. Present Owner. Occupant. Use: Mark Twain Memorial, the former residence of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), now a house museum. The carriage house is a mixed-use structure and contains museum offices, conference space, a staff kitchen, a staff library, and storage space. Significance: Completed in 1874, the Mark Twain Carriage House is a multi-purpose barn with a coachman's apartment designed by architects Edward Tuckerman Potter and Alfred H, Thorp as a companion structure to the residence for noted American author and humorist Samuel Clemens and his family. Its massive size and its generous accommodations for the coachman mark this structure as an unusual carriage house among those intended for a single family's use. The building has the wide overhanging eaves and half-timbering typical of the Chalet style popular in the late 19th century for cottages, carriage houses, and gatehouses. The carriage house apartment was -

Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn As Anti Racist Novel

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.46, 2018 Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn as Anti Racist Novel Ass.Lecturer Fahmi Salim Hameed Imam Kadhim college for Islamic science university, Baghdad , Iraq "Man is the only Slave. And he is the only animal who enslaves. He has always been a slave in one form or another, and has always held other slaves in bondage under him in one way or another.” - Mark Twain Abstract Mark Twain, the American author and satirist well known for his novels Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer , grew up in Missouri, which is a slave state and which later provided the setting for a couple of his novels. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn are the two most well-known characters among American readers that Mark Twain created. As a matter of fact, they are the most renowned pair in all of American literature. Twain’s father worked as a judge by profession, but he also worked in slave-trade sometimes. His uncle, John Quarles, owned 20 slaves; so from quite an early age, Twain grew up witnessing the practice of slave-trade whenever he spent summer vacations at his uncle's house. Many of his readers and critics have argued on his being a racist. Some call him an “Unexcusebale racist” and some say that Twain is no where even close to being a racist. Growing up in the times of slave trade, Twain had witnessed a lot of brutality and violence towards the African slaves. -

The Social Consciousness of Mark Twain

THE SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS OF MARK TWAIN A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Social Sciences Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Rose W. Caudill December 1975 AP p~ ~ /THE ScS 9\t l\ (__ ~'1\AJ Accepted by the faculty of the School of Social Sciences, Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the Ma ster of Arts in Hist ory degree. Master ' s Commi ttee : (date TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • . • • . I Chapter I. FEMINISM . 1 II. MARK 1WAIN 1 S VIEWS ON RELIGION 25 III. IMPERIALISM 60 REFERENCES •••• 93 Introduction Mark Twain was one of America's great authors. Behind his mask of humor lay a serious view of life. His chief concern, . was man and how his role in society could be improved. Twain chose not to be a crusader, but his social consciousness in the areas of feminism, religion, and imperialism reveal him to be a crusader at heart. Closest to Twain's heart were his feminist philosophies. He extolled the ideal wife and mother. Women influenced him greatly·, and he romanticized them. Because of these feelings of tenderness and admiration for women, he became concerned about ·the myth of their natural inferiority. As years passed, Twain's feminist philosophies included a belief in the policital, economic, and social equality of the sexes. Maternity was regarded as a major social role during Twain's lifetime since it involved the natural biological role of women. The resu·lting stereotype that "a woman I s place is in the home" largely determined the ways in which women had to express themselves. -

Petition Requesting Exclusive Use Extension for Pyroxasulfone

TITLE Petition for 3 Years Extension of Exclusive Data Use for Pyroxasulfone as Provided for Under FIFRA Section 3(c) (1) (F) (ii) TEST GUIDELINE None AUTHOR(S) Kimberly Pennino Lisa Ayn Setliff Nobuyuki Hasebe REPORT DATE December 20, 2019 REPORT NUMBER LI-134-2019-05 SPONSOR K-I CHEMICAL U.S.A., INC. c/o Landis International, Inc. P. O. Box 5126 Valdosta, GA 31603-512 SUBMITTER LANDIS INTERNATIONAL, INC. 3185 Madison Highway Valdosta, GA 31605 PAGE COUNT 1 of 91 Extension of Exclusive Data Use for Pyroxasulfone K-I Chemical U.S.A, Inc. STATEMENT OF NO DATA CONFIDENTIALITY CLAIM No claim of confidentiality, on any basis whatsoever, is made for any information contained in this document. I acknowledge that information not designated as within the scope of FIFRA sec. l0(d)(l)(A), (B), or (C) and which pertains to a registered or previously registered pesticide is not entitled to confidential treatment and may be released to the public, subject to the provisions regarding disclosure to multinational entities under FIFRA l0(g). Submitter Signature: ______________________________ Date: ________________ Typed Name of Signer: Lisa Ayn Setliff, Vice Pres., Regulatory Affairs Typed Name of Company: Landis International, Inc. Page 2 of 91 Extension of Exclusive Data Use for Pyroxasulfone K-I Chemical U.S.A, Inc. GOOD LABORATORY PRACTICE COMPLIANCE STATEMENT This document is not a study and therefore is not in accordance with 40 CFR 160. Study Director Signature: N/A – This document is not subject to GLP standards. Sponsor Signature: ____________________________________________ ______ __________________ Date: ______________December 20, 2019 Typed Name of Signer: Nobuyuki Hasebe Typed Name of Company: K-I CHEMICAL U.S.A., INC. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1965 ST. LOUIS LEVEE, 1871 The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 Roy D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President LEWIS E. ATHERTON, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. Louis R. I. COLBORN, Paris GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe VICTOR A. GIERKE, Louisiana WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1966 BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville STANLEY J. GOODMAN, St. Louis W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C. THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1967 WILLIAM AULL, III, Lexington *FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis JAMES TODD, Moberly GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City T. -

Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn

THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER & HUCKLEBERRY FINN CAST OF CHARACTERS: Showboat Captain (also plays Percy, Injun Joe, Preacher) Dolly, Captain's wife (also plays Aunt Polly, Schoolteacher) Tom Sawyer Harley, the first mate (plays Jim) Colin, showboat actor (plays Huck) Abigail, showboat actress (plays Becky) AS THE LIGHTS COME UP WE SEE A SHOWBOAT UPSTAGE. THE PADDLEWHEEL IS STILL TURNING AND SMOKE STILL FLOWS FROM THE SMOKESTACK THE BOAT HAS JUST DOCKED AT A WHARF. THE SHOWBOAT CREW AND COMPANY ARE ON HE DECK SINGING AND WAVING. AS THEY SING THE GANGPLANK IS LOWERED AND THEY SET UP THEm "PLAYING AREA" BOTH ON AND OFF THE BOAT. ON DECK IS THE CAPTAIN OF THE SHOWBOAT, A MAN OF :MIDDLE YEARS WHO IS PROBABLY MORE OF A SHOWMAN THAN A SEAMAN; THE CAPTAIN'S WIFE, DOLLY WHO IS ALSO THE LEADING LADY; ABIGAIL, THE INGENUE; HARLEY, THE FmST MATE; AND COLIN, THE JUVENILE AND LEADING MAN. HERE IT COMES, HERE IT COMES! HEY, LOOK UP THE RIVER, IT'S A SHOWBOAT HERE IT COMES, HERE IT COMES! CHUG A LUG! CHUG A LUG! CHUG A LUG! HEY! HERE IT COMES! LOOK UP THE RIVER, THERE'S A BOAT A-COMIN HUSH UP AND LISTEN TO THE MOTOR IillMMIN IT'S A SHOWBOAT! GREAT LAND 0 ' GOSHEN! THERE'S A SHOWBOAT PULLIN IN TODAY. AINT NO DOUBTIN THERE'LL BE SONGS FOR SIN GIN GOTTA BE THERE SHOUTIN WHEN THE BELLS START RINGIN ON THE SHOWBOAT. GREAT LAND 0 ' GOSHEN! THERE'S A SHOWBOAT PULLIN IN TODAY. THE BOAT'S FINISHED DOCKIN AND THE PADDLEWHEEL IS STOPPIN LISTEN UP AND YOU'LL HEAR THE CAPTAIN SAY.. -

1. the Art of Selling Without Being 'Salesy' How Do You Ask

1. The Art of Selling Without Being ‘Salesy’ How do you ask a girl out? Do you start with talking about yourself? Do you remind them how you are the best she’ll ever meet? No! (Until, of course, you want to drive them away) Then why do you do it as a brand? Of course, it is important to convince your target audience about how you or your product are the one-stop solution to the current challenges they’re facing. But think about this - have you really seen doctors go about ‘selling’ their skills/profession? No! They put their stakes on word of mouth marketing. Still, they are one of the highest grossers we know! That’s the case of services, you’d say. How about products? You just can’t sit back and wait for someone to recommend your product to your target market. You’ve to be aggressive, out there. Agreed. But being aggressive ≠ being salesy. An aggressive salesperson will put his blood and sweat in creating the need for the product/service and solving his prospects’ most pressing challenges. A ‘salesy’ salesperson, on the other hand, will try and convince the prospects that his product/service is right for them irrespective of what their problem is. Aggressive salesperson is targeted; salesy salesperson just wants to meet the targets. Indeed, a very thin line. Source Let’s take another example to understand this better. “Our core competency is helping struggling outfits like yours get buy-in from bigger clients. We really moved the needle for XYZ corporation, which landed a big contract with Microsoft. -

Southern Ambivalence: the Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris William R. Bell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, William R., "Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625262. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mr8c-mx50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Southern Ambivalence: h The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William R. Bell 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626489 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626489 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

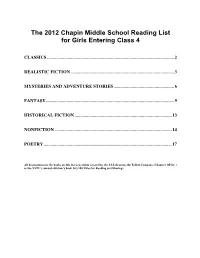

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

Theatre Company to Perform Big River This Month Seven Performances July 20-21 and 26-28 • L.J

July 13, 2012 For Immediate Release Contact: Robert Herman Public Information Officer (559) 733-6606 – office (559) 303-8568 – cell Tulare County Office of Education Announces: Theatre Company to perform Big River this month Seven performances July 20-21 and 26-28 • L.J. Williams Theater, 1001 W. Main St., Visalia The Tulare County Office of Education’s Theatre Company will present seven performances of the Tony Award-winning musical Big River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at the L.J. Williams Theater in Visalia beginning next week. The musical is the Theatre Company’s 15th annual summer production. Five evening shows will be held at 7:30 p.m. on July 20, 21, 26, 27 and 28. Two matinee shows will be held at 2:00 p.m. on Saturday, July 21 and 28. The musical is an adaptation of Mark Twain’s much-loved 1884 novel, featuring music and lyrics by American songwriter and Grammy Award winner Roger Miller. The year that the production debuted on Broadway, it won seven Tony’s, including best musical and best score for composer Miller. In the musical, as in the book, Huck Finn runs away from his abusive father to live in the wilderness along the Mississippi River. There, he encounters a slave named Jim, who has also run away. Jim is trying to make his way to Ohio, a free state, so he can buy his family’s freedom. ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 2637 W. Burrel Ave., P.O. Box 5091; Visalia, CA 93278-5091 h 559/733-6300 h 559/737-4378 h www.tcoe.org PRINCIPLE CHARACTERS ACTOR/SCHOOL Mark Twain Alex Galvan, Tulare Union High School Huckleberry Finn Tristan Peck, El Diamante High School (Visalia) Jim Harrison Mills (adult) Tom Sawyer Samuel Quinzon, Mt. -

(9) the Keys of the Kingdom

Alco_9781893007161_6p_01_r6_Alco_1893007162_6p_01_r6.qxd 11/20/13 3:40 PM Page 268 (9) THE KEYS OF THE KINGDOM This worldly lady helped to develop A.A. in Chicago and thus passed her keys to many. little more than fifteen years ago, through A a long and calamitous series of shattering ex- periences, I found myself being helplessly propelled toward total destruction. I was without power to change the course my life had taken. How I had arrived at this tragic impasse, I could not have explained to anyone. I was thirty-three years old and my life was spent. I was caught in a cycle of alcohol and sedation that was proving inescapable, and consciousness had become intolerable. I was a product of the post-war prohibition era of the Roaring ’20s. That age of the flapper and the “It” girl, speakeasies and the hip flask, the boyish bob and the drugstore cowboy, John Held Jr. and F. Scott Fitz - gerald, all generously sprinkled with a patent pseudo- sophistication. To be sure, this had been a dizzy and confused interval, but most everyone else I knew had emerged from it with both feet on the ground and a fair amount of adult maturity. Nor could I blame my dilemma on my childhood environment. I couldn’t have chosen more loving and conscientious parents. I was given every advantage in a well-ordered home. I had the best schools, sum- mer camps, resort vacations, and travel. Every reason- 268 Alco_9781893007161_6p_01_r6_Alco_1893007162_6p_01_r6.qxd 11/20/13 3:40 PM Page 269 THE KEYS OF THE KINGDOM 269 able desire was possible of attainment for me. -

Literary Destinations

LITERARY DESTINATIONS: MARK TWAIN’S HOUSES AND LITERARY TOURISM by C2009 Hilary Iris Lowe Submitted to the graduate degree program in American studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester _________________________________________ Dr. Susan K. Harris _________________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield _________________________________________ Dr. John Pultz _________________________________________ Dr. Susan Earle Date Defended 11/30/2009 2 The Dissertation Committee for Hilary Iris Lowe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Literary Destinations: Mark Twain’s Houses and Literary Tourism Committee: ____________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester, Chairperson Accepted 11/30/2009 3 Literary Destinations Americans are obsessed with houses—their own and everyone else’s. ~Dell Upton (1998) There is a trick about an American house that is like the deep-lying untranslatable idioms of a foreign language— a trick uncatchable by the stranger, a trick incommunicable and indescribable; and that elusive trick, that intangible something, whatever it is, is the something that gives the home look and the home feeling to an American house and makes it the most satisfying refuge yet invented by men—and women, mainly by women. ~Mark Twain (1892) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 ABSTRACT 7 PREFACE 8 INTRODUCTION: 16 Literary Homes in the United