Scribal Traditions and Administration at Emar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

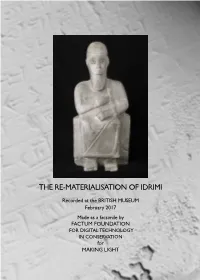

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

New Horizons in the Study of Ancient Syria

OFFPRINT FROM Volume Twenty-five NEW HORIZONS IN THE STUDY OF ANCIENT SYRIA Mark W. Chavalas John L. Hayes editors ml"ITfE ADMINISTRATION IN SYRIA IN THE LIGHT OF THE TEXTS FROM UATTUSA, UGARIT AND EMAR Gary M. Beckman Although the Hittite state of the Late Bronze Age always had its roots in central Anatolia,1 it continually sought to expand its hegemony toward the southeast into Syria, where military campaigns would bring it booty in precious metals and other goods available at home only in limited quantities, and where domination would assure the constant flow of such wealth in the fonn of tribute and imposts on the active trade of this crossroads between Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Aegean. Already in the 'seventeenth century, the Hittite kings ~attu§ili I and his adopted son and successor Mur§ili I conquered much of this area, breaking the power of the "Great Kingdom" of ~alab and even reaching distant Babylon, where the dynasty of ~ammurapi was brought to an end by Hittite attack. However, the Hittites were unable to consolidate their dominion over northern Syria and were soon forced back to the north by Hurrian princes, who were active even in eastern Anatolia.2 Practically nothing can be said concerning Hittite administration of Syria in this period, known to Hittitologists as the Old Kingdom. During the following Middle Kingdom (late sixteenth-early fourteenth centuries), Hittite power was largely confined to Anatolia, while northern Syria came under the sway 1 During the past quarter century research in Hittite studies bas proceeded at such a pace that there currently exists no adequate monographic account ofAnatolian history and culture of the second millennium. -

David J.A. Clines, "Regnal Year Reckoning in the Last Years of The

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGY REGNAL YEAR RECKONING IN THE LAST YEARS OF THE KINGDOM OF JUDAH D. J. A. CLINES Department of Biblical Studies, The University of Sheffield A long debated question in studies of the Israelite calendar and of pre-exilic chronology is: was the calendar year in Israel and Judah reckoned from the spring or the autumn? The majority verdict has come to be that throughout most of the monarchical period an autumnal calendar was employed for civil, religious, and royal purposes. Several variations on this view have been advanced. Some have thought that the spring reckoning which we find attested in the post-exilic period came into operation only during the exile, 1 but many have maintained that the usual autumnal calendar gave way in pre-exilic Judah to a spring calendar as used by Assyrians and Babylonians.2 Some have 1. So e.g. J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (ET, Edinburgh, 1885, r.p. Cleveland, 1957), 108f.; K. Marti, 'Year', Encyclopaedia Biblica, iv (London, 1907), col. 5365; S. Mowinckel, 'Die Chronologie der israelitischen und jiidischen Konige', Acta Orien talia 10 (1932), 161-277 174ff.). 2. (i) In the 8th century according to E. Kutsch, Das Herbst/est ill Israel (Diss. Mainz, 1955), 68; id., RGG,3 i (1957), col. 1812; followed by H.-J. Kraus, Worship in Israel (ET, Richmond, Va., 1966), 45; similarly W. F. Albright, Bib 37 (1956), 489; A. Jepsen, Zllr Chronologie der Konige von Israel lInd Judo, in A. Jepsen and R. Hanhart, Ullter sllchllngen zur israelitisch-jiidischen Chrollologie (BZAW, 88) (Berlin, 1964), 28, 37. -

A Political History of the Arameans

A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS Press SBL ARCHAEOLOGY AND BIBLICAL STUDIES Brian B. Schmidt, General Editor Editorial Board: Aaron Brody Annie Caubet Billie Jean Collins Israel Finkelstein André Lemaire Amihai Mazar Herbert Niehr Christoph Uehlinger Number 13 Press SBL A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities K. Lawson Younger Jr. Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2016 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and record- ing, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Younger, K. Lawson. A political history of the Arameans : from their origins to the end of their polities / K. Lawson Younger, Jr. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical literature archaeology and Biblical studies ; number 13) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-128-5 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837- 080-5 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837-084-3 (electronic format) 1. Arameans—History. 2. Arameans—Politics and government. 3. Middle East—Politics and government. I. Title. DS59.A7Y68 2015 939.4'3402—dc23 2015004298 Press Printed on acid-free paper. SBL To Alan Millard, ֲאַרִּמֹי אֵבד a pursuer of a knowledge and understanding of Press SBL Press SBL CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... -

Fernand Braudel IFER Fellowships

Dr. Maurizio Viano Fernand Braudel IFER Fellowships Research Project Syria at the Crossroad of Empires: The Politic and Economic Framework of Urban Centres in Late Bronze Age Syria The Late Bronze Age (1600 - 1200 B.C.) in the ancient Near East is usually termed by scholars as the International Period because of the international relationships that took place among the so-called great powers (i.e. Babylonia, Assyria, Mitanni, Hittite kingdom, Egypt) and among their vassals (local domains). During this period the Syro-Palestinian area was the scene of the activities of Egypt, Mitanni, Hatti and Assyria. Several minor local kingdoms developed under the rule of the great powers. The presented project aims to explore the socio-political structures of Syrian urban centres during the 14th and 13th century B.C. in relation to their economy. This is important as it will help our understanding of a crucial moment in the ancient Near Eastern history, namely the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. The research project will mainly focus on the Middle Euphrates region and Emar, a city on the west-bank of the river (which was first under the Mitannian rule and later under the control of the Hittite Empire. This city is already mentioned in the third millennium in the texts from Ebla, but textual finds date to a period between the 14th and 12th century. Over one thousand cuneiform tablets were unearthed in a salvage campaign in the 1970s by a French team and several other finds came from illegal excavations. The main bulk of the textual finds consists of economic and administrative texts, such as private contracts, wills, and administrative deeds related to the city temples/cult. -

The City of Emar Among the Late Bronze Age Empires History

The City of Emar among the Late Bronze Age Empires History, Landscape, and Society Proceedings of the Konstanz Emar Conference, 25.–26.04. 2006 Edited by Lorenzo d’Alfonso, Yoram Cohen, and Dietrich Sürenhagen 2008 Ugarit-Verlag Münster Late Bronze Age Rural Landscapes of the Euphrates according to the Emar Texts Hervé Reculeau, FU Berlin Valley landscapes of the Euphrates underwent drastic changes within the last decades, especially after the river was dammed in Tabqa (1973-1974) and Tišrin (1999); albeit destructive of the present environment, these modern upheavals were also the source of a great increase of knowledge regarding ancient landscapes, according to both archaeology and epigraphy. The whole area of the Great Bend of the Euphrates, nowadays under water, has been thoroughly prospected and numerous salvage excavations were made at major sites1, and the valley downstream (up to the Halabiyeh-Zalebiyeh area) was surveyed, with a special focus on natural environment and river-based destruction of sites2. Multidisciplinary studies aiming at the reconstruction of ancient environments were undertaken on different sites of the area, such as Selenkahiye3, Tell es-Sweyhat4 or, in the Bend proper, Tell Munbāqa (Ekalte) where remains of Bronze Age plants were found5. At Emar, the time frame of salvage excavations did not allow such data to be collected, although a few remarks were made on the geographical situation of the city and its relationship to the river in its present and reconstructed past location6. However, the new Syro- German excavations on the preserved part of the site7 fortunately revealed plant remains, which now allow an environmental reconstruction based on the Emar documentation itself8. -

Military at Emar-VII Inglés

WARFARE AND THE ARMY AT EMAR Juan-Pablo Vita (CSIC-Madrid) 1. Introduction The State of Emar does not seem to have represented a political and military power at any time during its history1. The Emar of the Middle Bronze Age was mostly an important commercial emporium2, thanks to the strategic geographical location of the site, in the centre of the main commercial routes over land and by river that linked Assyria with the North of Mesopotamia. From the political standpoint, it was the most advanced post of the Kingdom of Aleppo against the Kingdom of Mari. This borderline position, at the converging point of two great Kingdoms, made it unavoidable for Emar to be involved in military episodes, of which there seem to be indirect indications3. 1.2. Later on, in the Late Bronze Age, the geographical location of the city led to Emar again being at the contact point between powerful Kingdoms. This period in the history of Emar is illustrated directly by archives that were made and found in the city itself. The purpose of this article is to gather and assess the elements that are contained in those files regarding warfare and the army. As is to be expected, the information that they provide regarding this issue mainly concerns the Kingdom of Emar under Hittite control. In this period Emar was not prominent from the military standpoint, but texts show that the city did possess an army, no doubt controlled by and partly composed of Hittite troops, and they contain elements of historical interest in the matter. -

1 Is There a Connection Between the Amorites and the Arameans?

1 Is There a Connection Between the Amorites and the Arameans? Daniel Bodi University of Paris 8 Abstract: A steady flow of new documents and scholarly publications dealing with the history of ancient Syria, the Amorites and the Arameans makes it possible to attempt a new synthesis of the data, revise previous views and propose some new ones. This article suggests several new arguments for the possibility of seeing some continuity between the 18th century BCE Amorites and the 12th century BCE Arameans. First, the geographical habitat of the various Amorite Bensimʾalite and Benjaminite tribes and the Aramean tribal conglomerates is compared. Second, the pattern of migration of the Amorite and Aramean tribes is analyzed. Third, some common linguistic elements are enumerated, like the term Aḫlamu found among the Amorites and the Arameans. Fourth, the attempt of some scholars to place the Hebrew ancestors among the Aramean tribes in Northern Syria is discussed. And fifth, some matrimonial institutions, customs, social and linguistic phenomena common to the Amorites and the Hebrews are pointed out attesting to a cultural continuity of certain practices spanning several centuries. Introduction The issue of the connection or its absence between the Amorites and the Arameans is an old one. The discussion is about to reach a century of scholarly publications and debates. It began with the discussion of the “Amorite question” dealing with the time span and geographical area to which Amorite tribes can be assigned, the linguistic analysis of the geographical and personal names associated with them, and the very name by which they should be designated. -

Umm El-Marra and the Westward Expansion of the Mittani Empire

UMM EL-MARRA AND THE WESTWARD EXPANSION OF THE MITTANI EMPIRE IN NORTHWESTERN SYRIA by Adam Sebastian Maskevich A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March, 2014 © 2014 Adam Sebastian Maskevich All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Bronze Age occupation of Umm el-Marra, a medium-sized regional center in western Syria, lasted, with varying degrees of intensity, for more than a millennium. During this time, the communities who inhabited the site and the political regimes that ruled them left their unique marks on the built environment and material culture. This dissertation studies these phenomena during the Late Bronze Age occupation of Umm el-Marra in the mid-second millennium through a synthesis of the excavation records of the site, archaeological comparanda, textual evidence, ethnoarchaeology, and applicable theory. The Mittani Empire was the dominant power in northern Syria during the Late Bronze occupation of Umm el-Marra. Most of what is known about Mittani comes from external sources, many of whom were antagonistic and, thus, provide a biased view of the empire and its inhabitants. Through analysis of the Late Bronze Age levels at Umm el-Marra, this work provides an evaluation and exploration of the nature of everyday life in the Mittani empire. As such, it offers a new resource for understanding Mittani, in particular, and the functioning of imperial regimes in general, from the perspective of daily lived existence in households, neighborhoods, and a specific community. As communities and their constituent families change over time, they have different needs of the dwellings and landscapes they inhabit. -

After the Hittites: the Kingdoms of Karkamish and Palistin in Northern Syria

AFTER THE HITTITES: THE KINGDOMS OF KARKAMISH AND PALISTIN IN NORTHERN SYRIA MARK WEEDEN Introduction: deconstructing the ‘sea-peoples’ During the twelfth century BC numerous large-scale, palace-centred, and/or imperial state- formations either apparently disappeared, or transformed into other political entities, or are supposed to have experienced significant contraction: the Hittite Empire, the palace centres of Mycenaean Greece, Egypt’s empire in the Levant, Assyria, and Babylonia, although the last two were less radically affected.1 The western contours of this collapse (Levant and Anatolia) are frequently associated, whether as symptom or cause, with the rise to prominence of various peoples and social formations partially subsumed under the misleading term ‘sea-peoples’.2 The following historical period is frequently referred to as a Dark Age because of the apparent lack of written sources throughout the eastern Mediterranean, at least by contrast with the abundant documents of the periods before and after; it is roughly coterminous with the archaeological period of the Early Iron Age (c. 1200-900 BC, also Iron Age I). But new excavations, new finds of inscriptions written in Hieroglyphic Luwian, and an improved understanding of previously available ones, are profoundly changing our image of the North Syrian region west of the Euphrates, which had been dominated by the Hittite empire for the previous roughly 150 years.3 Hieroglyphic Luwian refers to the script (Anatolian Hieroglyphs) and the language (Luwian, a language closely related to Hittite) which are used on Iron Age, i.e. post-1200 BC, inscriptions written according to iconographic and rhetorical norms which largely 1 See e.g. -

UGARIT-FORSCHUNGEN Loretz, Oswald Der Ugaritisch-Hebraische Parallelismus Rkb '1Pt II Rkb B 'Rbwt in Psalm 68,5

Sonderdruck aus: Lo retz, Oswald Ugaritisch ap (III) und syllabisch-keil schriftlich abi/ apu als Vorlaufcr von hebraisch 'ab / 'ob ,(Kult/Nekromanti e-)Gmbe". Ein Beitrag zu Nekromantie und Magie in Ugarit, Emar und Israel ...... .. ....... 48 1 UGARIT-FORSCHUNGEN Loretz, Oswald Der ugaritisch-hebraische Parallelismus rkb '1pt II rkb b 'rbwt in Psalm 68,5 ........ .... ..... .. .. .. .. .. ..................... ... ..... ... ..... ... ... 521 Mallet, Joel Internationales J ahrbuch Ras Shamra-Ougarit (Syric), 62c campagne, 2002. L'exploration des niveaux du Bronze moyen II ftir die ( I rc mo itie du rrc mi llena ire av. J. -C.) so us le palais nord .. ... .. .... ... .. .. ...... 527 Mallet, Joel, et Lebrun, Rene Altertumskunde Syrien-PaHistinas Document SOliS sceau hittite, ccriture et langue adech iffrer .. ...... .. ... ... .. .. .. 55 1 Mazzini, Giovanni A New Suggestion to KTU 1.14 I 15 ...... ... ... ... ............ .. .. ............. .. 569 Mazzini, Giovanni Akkadian R'M as a West Semitic Lexical Trait ... ... ....... .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .. 577 Na'aman, Nadav Herausgeber The Abandonment of Cult Places in the Kingdoms Manfried Dietrich · Oswald Loretz of Israe l and Judah as Acts of Cult Reform .. .. .. .. ............ .. .. .. ... ........ .. 585 Richter, Thomas Der , Einjahrige Feldzug" Suppi luliumas I. von Ij.atti in Syrien nach Textfunden des Jahres 2002 in Mi srife/Qa!na .. ... .. .. .. .... .. ..... 603 Beratergremium Shatnawi, Ma'en Al i Die Personennamen in den !amudischen Inschriften. J. Bretschneider • I. Kottsieper • K.A. Metzler Eine lexikal isch-grammatische Analyse im Rahmen R. Schmitt • J. Tropper • W.H. van Soldt • J.-P. Vita der gemeinsemitischen Namengebung ............ .. ... .. ... .. .................... .. .619 Strawn, Brent A. wenil'ii(h), "0 V,ictorious One," in Ps 68, 10 .. .. ........... ... .......... .. ........... 785 Tropper, Josef Zur Rekonstruktion von KTU 1.4 VII 19 ..... .................................. .... .. 799 van Soldt, Wilfred Stud ies on the siikinu-Officia l (2) . -

Ebla's Hegemony and Its Impact on the Archaeology of the Amuq Plain

Ebla’s Hegemony and Its Impact on the Archaeology of the Amuq Plain in the Third Millennium BCE by Steven Edwards A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Steven Edwards, 2019 Ebla’s Hegemony and Its Impact on the Archaeology of the Amuq Plain in the Third Millennium BCE Steven Edwards Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Studies University of Toronto 2019 Abstract This dissertation investigates the emergence of Ebla as a regional state in northwest Syria during the Early Bronze Age and provides a characterization of Ebla that emphasizes its hegemonic rather than imperial features. The texts recovered from the Royal Palace G archives reveal that Ebla expanded from a small Ciseuphratean kingdom into a major regional power in Upper Mesopotamia over the course of just four or five decades. To consolidate and maintain its rapidly growing periphery, Ebla engaged in intensive diplomatic relations with an array of client states, semi-autonomous polities, and independent kingdoms. Often, political goals were achieved through mutual gift-exchange and interdynastic marriage, but military activity became increasingly common towards the end of the period covered by the texts. However, apart from installing palace officials at some cities, Ebla did not appear to have invested heavily in building infrastructure, such as roads or forts, along its periphery, preferring instead to leave matters of defense up to client and allied states. As a result, the archaeological impact of Ebla’s political hegemony along parts of its periphery was minimal.