Ebla's Hegemony and Its Impact on the Archaeology of the Amuq Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extracts Relating to the Hittites from the Tel El-Amarna Letters

APPENDIX EXTRACTS RELATING TO THE HITTITES FROM THE TEL EL-AMARNA LETTERS ROM a letter of Dusratta, king of Mitanni: 1 When F all the [army] of the Hittites marched to attack my country, Tessub my lord gave it into my hands and I smote it. There was none among them who returned to his own land.' From a letter of Aziru, son of Ebed-Asherah the Amorite, to the Egyptian official Dudu : 1 0 my lord, now Khatip (Hotep) is with me. I and he will march (together). 0 my lord, the king of the land of the Hittites has marched into the land of Nukhassi (Egyp!t"an Anaugas), and the cities (there) are not strong enough to defend themselves from the king of the Hittites ; but now I and Khatip will go (to their help).' From a letter of Aziru to the Egyptian official Khai : 1 The king of the land of the Hittites is in Nukhassi, and I am afraid of him; I keep guard lest he make his way up into the land of the Amorites. And if the city of Tunip falls there will be two roads (open) to the place where he is, and I am afraid of him, and on this account I have remained (here) till his departure. But now I and Khatip will march at once.' From a letter of Aziru to the Pharaoh : 1 And now the king of the Hittites is in Nukhassi: there are two roads to Tunip, and I am afraid it will fall, and that the city [will not be strong enough] to defend itself.' Appendix From a letter of Akizzi, the governor of Qatna (in Nukhassi) on the Khabur to the Pharaoh: 1 0 my lord, the Sun-god my father made thy fathers and set his name upon them ; but now the king of the Hittites has taken the Sun-god my father, and my lord knows what they have done to the god, how it stands. -

Field Development-A3-EN-02112020 Copy

FIELD DEVELOPMENTS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC NORTH EAST AND NORTH WEST SYRIA ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ Violations committed by ١,٠٩١ the Regime and its Russian ally of the ceasefire truce ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ Control Parties ;٢٠٢٠ March ٥ After the Turkish and Russian Presidents reached the ceasefire truce agreement in Idleb Governorate on the warplanes of the regime and its Russian ally didn’t bomb North Western Syria ever since; yet the regime continued Russian warplanes have ;٢٠٢٠ June ٢ targeting the cities and towns there with heavy artillery and rocket launchers; on again bombed northwestern Syria, along with the regime which continued targeting NW Syria with heavy artillery and ١,٠٩١ rocket launchers. Through its network of enumerators, the Assistance Coordination Unit ACU documented violations of the truce committed by the regime and its Russian ally as of the date of this report. There has been no change in the control map over the past week; No joint Turkish-Russian military patrols were carried the regime bombed with heavy ,٢٠٢٠ October ٢٧ on ;٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ out during the period between artillery the area surrounding the Turkish observation post in the town of Marj Elzohur. The military actions carried out ٣ civilians, including ٢٣ civilians, including a child and a woman, and wounded ٨ by the Syrian regime and its allies killed Regime .women ٣ children and Opposition group The enumerators of the Information Management Unit (IMU) of the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) documented in Opposition group affiliated by Turkey (violations of the truce in Idleb governorate and adjacent Syrian democratic forces (SDF ٦٨ m; ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ the period between countrysides of Aleppo; Lattakia and Hama governorates. -

Contacts: Crete, Egypt, and the Near East Circa 2000 B.C

Malcolm H. Wiener major Akkadian site at Tell Leilan and many of its neighboring sites were abandoned ca. 2200 B.C.7 Many other Syrian sites were abandoned early in Early Bronze (EB) IVB, with the final wave of destruction and aban- donment coming at the end of EB IVB, Contacts: Crete, Egypt, about the end of the third millennium B.c. 8 In Canaan there was a precipitous decline in the number of inhabited sites in EB III— and the Near East circa IVB,9 including a hiatus posited at Ugarit. In Cyprus, the Philia phase of the Early 2000 B.C. Bronze Age, "characterised by a uniformity of material culture indicating close connec- tions between different parts of the island"10 and linked to a broader eastern Mediterra- This essay examines the interaction between nean interaction sphere, broke down, per- Minoan Crete, Egypt, the Levant, and Ana- haps because of a general collapse of tolia in the twenty-first and twentieth cen- overseas systems and a reduced demand for turies B.c. and briefly thereafter.' Cypriot copper." With respect to Egypt, Of course contacts began much earlier. Donald Redford states that "[t]he incidence The appearance en masse of pottery of Ana- of famine increases in the late 6th Dynasty tolian derivation in Crete at the beginning and early First Intermediate Period, and a of Early Minoan (EM) I, around 3000 B.C.,2 reduction in rainfall and the annual flooding together with some evidence of destructions of the Nile seems to have afflicted northeast and the occupation of refuge sites at the time, Africa with progressive desiccation as the suggests the arrival of settlers from Anatolia. -

Cold and Dry Outbreaks in the Eastern Mediterranean 3200 Years

https://doi.org/10.1130/G46491.1 Manuscript received 13 May 2019 Revised manuscript received 17 July 2019 Manuscript accepted 17 July 2019 © 2019 Geological Society of America. For permission to copy, contact [email protected]. Published online XX Month 2019 Cold and dry outbreaks in the eastern Mediterranean 3200 years ago David Kaniewski1*, Nick Marriner2, Rachid Cheddadi3, Christophe Morhange4, Joachim Bretschneider5, Greta Jans6, Thierry Otto1, Frédéric Luce1, and Elise Van Campo1 1EcoLab, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, INP, UPS, 31062 Toulouse cedex 9, France 2 Laboratoire Chrono-Environnement UMR6249, Maison des sciences de l’homme et de l’environnement Claude Nicolas Ledoux USR 3124, CNRS, Université de Franche-Comté, UFR ST, 16 Route de Gray, 25030 Besançon, France 3Université Montpellier II, CNRS-UM2-IRD, ISEM, 34090 Montpellier, France 4Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, IRD, INRA, Collège de France, CEREGE, 13545 Aix en Provence, cedex 04, France 5Department of Archaeology–Ancient Near East, Faculty of Art and Philosophy, Ghent University, Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat 35, 9000 Gent, Belgium 6Near Eastern Studies, Faculteit Letteren, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Blijde-Inkomststraat 21, 3000 Leuven, Belgium ABSTRACT depict similar trends, evoking a severe climate Can climate affect societies? This question, of both past and present importance, is encap- shift of regional extent (Kaniewski et al., 2015). sulated by the major socioeconomic crisis that affected the Mediterranean 3200 yr ago. The Nonetheless, the quantifcation of changes in demise of the core civilizations of the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean during the Late rainfall regime and temperature has proved chal- Bronze Age and the early Iron Age (Dark Ages) is still controversial because it raises the ques- lenging until now, in part owing to the scarcity tion of climate-change impacts on ancient societies. -

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions

MISCELLANEOUS BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS BY GEORGE A. BARTON PROFESSOR IN BRYN MAWR COLLEGE ttCI.f~ -VIb NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVIII COPYRIGHT 1918 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published, August, 191 8. TO HAROLD PEIRCE GENEROUS AND EFFICIENT HELPER IN GOOD WORKS PART I SUMERIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE The texts in this volume have been copied from tablets in the University Museum, Philadelphia, and edited in moments snatched from many other exacting duties. They present considerable variety. No. i is an incantation copied from a foundation cylinder of the time of the dynasty of Agade. It is the oldest known religious text from Babylonia, and perhaps the oldest in the world. No. 8 contains a new account of the creation of man and the development of agriculture and city life. No. 9 is an oracle of Ishbiurra, founder of the dynasty of Nisin, and throws an interesting light upon his career. It need hardly be added that the first interpretation of any unilingual Sumerian text is necessarily, in the present state of our knowledge, largely tentative. Every one familiar with the language knows that every text presents many possi- bilities of translation and interpretation. The first interpreter cannot hope to have thought of all of these, or to have decided every delicate point in a way that will commend itself to all his colleagues. The writer is indebted to Professor Albert T. Clay, to Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., and to Dr. Stephen Langdon for many helpful criticisms and suggestions. Their wide knowl- edge of the religious texts of Babylonia, generously placed at the writer's service, has been most helpful. -

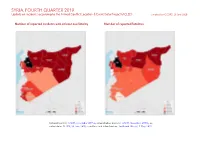

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

3 a Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36

3 A Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36 3.1 Introduction CCs may be classified according to a number of characteristics. Jagersma (2010, pp. 687-705) gives a detailed description of Sumerian CCs arranged according to the types of constituents that may function as S or PC. Jagersma’s description is the most detailed one ever written about CCs in Sumerian, and particularly, the parts on clauses with a non-finite verbal form as the PC are extremely insightful. Linguistic studies on CCs, however, discuss the kind of constituents in CCs only in connection with another kind of classification which appears to be more relevant to the description of CCs. This classification is based on the semantic properties of CCs, which in turn have a profound influence on their grammatical and pragmatic properties. In this chapter I will give a description of CCs based mainly on the work of Renaat Declerck (1988) (which itself owes much to Higgins [1979]), and Mikkelsen (2005). My description will also take into account the information structure of CCs. Information structure is understood as “a phenomenon of information packaging that responds to the immediate communicative needs of interlocutors” (Krifka, 2007, p. 13). CCs appear to be ideal for studying the role information packaging plays in Sumerian grammar. Their morphology and structure are much simpler than the morphology and structure of clauses with a non-copular finite verb, and there is a more transparent connection between their pragmatic characteristics and their structure. 3.2 The Classification of Copular Clauses in Linguistics CCs can be divided into three main types on the basis of their meaning: predicational, specificational, and equative. -

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

Syrian Arab Republic: Thematic Study on Land Reclamation Through De-Rocking

NEAR EAST AND NORTH AFRICA DIVISION Syrian Arab Republic: Thematic study on land reclamation through de-rocking Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty Syrian Arab Republic: Thematic study on land reclamation through de-rocking Southern Regional Agricultural Development Project (SRADP) Jebel al Hoss Agricultural Development Project (JHADP) Coastal/Midlands Agricultural Development Project (CMADP) Idleb Rural Development Project (IRDP) Near East and North Africa Division Programme management department Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty Table of contents Currency equivalent. 5 Weights and measures . 5 Abbreviations and acronyms . 6 I. Introduction. 7 Context and background . 7 Rationale and objectives . 9 Methodology and approach . 9 II. Resources, policy, institutional context and achievement . 11 Physiographic profile and land resources . 11 Government policy and agriculture-sector strategy . 17 Key institutions involved . 19 Land reclamation through de-rocking: Past and present programmes . 21 III. IFAD’s role and intervention in land reclamation . 28 Intended objectives and approaches . 28 Relevance of IFAD’s land-reclamation interventions to poor farmers . 28 Synthesis of project experience . 30 Socio-economic impact . 38 Environmental impact assessment . 40 IV. Lessons learned . 45 Appendixes Appendix 1: Thematic maps . 46 Appendix 2: Technical note on the de-rocking process . 52 Appendix 3: Supporting documents . 58 Appendix 4: Records of consultations . 60 3 List of tables Table 1. Major lithological features . 13 Table 2. Land-use distribution in 2006 by agricultural settlement zone (ASZ) . 14 Table 3. Farmed land distribution in 2006 by governorate . 15 Table 4. Syrian agricultural settlement zones (ASZs) . 15 Table 5. Areas planted with fruit trees by ASZ . 16 Table 6.