Preliminary Notes on a Newly Discovered Skull of the Extinct Monkey Antillothrix from Hispaniola and the Origin of the Greater Antillean Monkeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paralouatta Varonai. a New Quaternary Platyrrhine from Cuba

Manuel River0 Paralouatta varonai. a new Quaternary Faruldad de Biologia, 1 ~niversidadde platyrrhine from Cuba IA Habana, Ln Habana, Cuba Paralouatta varonai, new gen. and sp., from the Quaternary of Cuba, is diag- Oscar Arredondo nosed on the basis ofa skull lacking only portions of the face and the anterior dentition. Among extant platyrrhines, the new monkey shares important derived resemblances with Alouatta, including: (1) form of hafting of the neurocranium and face, (2) depth of malar corpus, and (3) marked lateral flaring of the maxillary root of the zygomatic process. It differs from Alouatta Received 27 June 1990 in mostly primitive ways, including: (1) presence of downwardly-directed Revision received 1 October 1990 foramen magnum, (2) less vertical orientation ofnuchal plane, and (3) curw and accepted I November 1990 of Spee opening less sharply upward. A conspicuous autapomorphy of P. vnronai is the extremely large size of the orbits, paralleled among living ~~vul~,rds;Platyrrhini, Atelidae. piatyrrhines only in Aotw. ~w&xuztln onrona:, Quaternary, Cuba, Fossil primates. journal oj Human .!hlution ( 1991) 21, l-1 1 introduction It is increasingly apparent that the Greater Antilles possessed a diverse array of platyrrhine primates during geologically recent times. To date, primate remains have been recovered from cave sites on three of these islands-Jamaica, Hispaniola and Cuba (Ameghino, 19 10; Miller, 1916, 1929; Williams & Koopman, 1952; Rimoli, 1977; MacPhee & Woods, 1982; Ford & Morgan, 1986,1988; Ford, 1990; MacPhee & Fleagle, in press). Some of this material has yet to be formally described and the number of good species represented in existing collections is unclear. -

An Extinct Monkey from Haiti and the Origins of the Greater Antillean Primates

An extinct monkey from Haiti and the origins of the Greater Antillean primates Siobhán B. Cookea,b,c,1, Alfred L. Rosenbergera,b,d,e, and Samuel Turveyf aGraduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016; bNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY 10016; cDepartment of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; dDepartment of Anthropology and Archaeology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY 11210; eDepartment of Mammalogy, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024; and fInstitute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom Edited* by Elwyn L. Simons, Duke University, Durham, NC, and approved December 30, 2010 (received for review June 29, 2010) A new extinct Late Quaternary platyrrhine from Haiti, Insulacebus fragment (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The latter preserves alveoli from toussaintiana, is described here from the most complete Caribbean left P4 to the right canine. subfossil primate dentition yet recorded, demonstrating the likely coexistence of two primate species on Hispaniola. Like other Carib- Etymology bean platyrrhines, I. toussaintiana exhibits primitive features resem- Insula (L.) means island, and cebus (Gr.) means monkey; The bling early Middle Miocene Patagonian fossils, reflecting an early species name, toussaintiana, is in honor of Toussainte Louverture derivation before the Amazonian community of modern New World (1743–1803), a Haitian hero and a founding father of the nation. anthropoids was configured. This, in combination with the young age of the fossils, provides a unique opportunity to examine a different Type Locality and Site Description parallel radiation of platyrrhines that survived into modern times, but The material was recovered in June 1984 from Late Quaternary ′ ′ is only distantly related to extant mainland forms. -

Stem Members of Platyrrhini Are Distinct from Catarrhines in at Least One Derived Cranial Feature

Journal of Human Evolution 100 (2016) 16e24 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Stem members of Platyrrhini are distinct from catarrhines in at least one derived cranial feature * Ethan L. Fulwood a, , Doug M. Boyer a, Richard F. Kay a, b a Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Box 90383, Durham, NC 27708, USA b Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA article info abstract Article history: The pterion, on the lateral aspect of the cranium, is where the zygomatic, frontal, sphenoid, squamosal, Received 3 August 2015 and parietal bones approach and contact. The configuration of these bones distinguishes New and Old Accepted 2 August 2016 World anthropoids: most extant platyrrhines exhibit contact between the parietal and zygomatic bones, while all known catarrhines exhibit frontal-alisphenoid contact. However, it is thought that early stem- platyrrhines retained the apparently primitive catarrhine condition. Here we re-evaluate the condition of Keywords: key fossil taxa using mCT (micro-computed tomography) imaging. The single known specimen of New World monkeys Tremacebus and an adult cranium of Antillothrix exhibit the typical platyrrhine condition of parietal- Pterion Homunculus zygomatic contact. The same is true of one specimen of Homunculus, while a second specimen has the ‘ ’ Tremacebus catarrhine condition. When these new data are incorporated into an ancestral state reconstruction, they MicroCT support the conclusion that pterion frontal-alisphenoid contact characterized the last common ancestor of crown anthropoids and that contact between the parietal and zygomatic is a synapomorphy of Platyrrhini. -

Neotropical Primates

ISSN 1413-4703 NEOTROPICAL PRIMATES A Journal of the Neotropical Section of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Volume 14 Number 1 January 2007 Editors Erwin Palacios Liliana Cortés-Ortiz Júlio César Bicca-Marques Eckhard Heymann Jessica Lynch Alfaro News and Books Reviews Brenda Solórzano Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna PSG Chairman Russell A. Mittermeier PSG Deputy Chairman Anthony B. Rylands SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION Neotropical Primates A Journal of the Neotropical Section of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA ISSN 1413-4703 Abbreviation: Neotrop. Primates Editors Erwin Palacios, Conservation International – Colombia Liliana Cortés-Ortiz, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Júlio César Bicca-Marques, Pontifícia Universidad Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brasil Eckhard Heymann, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany Jessica Lynch Alfaro, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA News and Books Reviews Brenda Solórzano, Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, México Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna, Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, México Founding Editors Anthony B. Rylands, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Arlington VA, USA Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna, Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, México Editorial Board Hannah M. Buchanan-Smith, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK Adelmar F. Coimbra-Filho, Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Carolyn M. Crockett, Regional Primate Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Stephen F. Ferrari, Universidade Federal do Sergipe, Aracajú, Brazil Russell A. Mittermeier, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA Marta D. Mudry, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Horácio Schneider, Universidade Federal do Pará, Campus Universitário de Bragança, Brazil Karen B. -

The Extinction of Xenothrix Mcgregori, Jamaica's Last Monkey

Journal of Mammalogy, 98(4):937–949, 2017 DOI:10.1093/jmammal/gyw165 The extinction of Xenothrix mcgregori, Jamaica’s last monkey SIOBHÁN B. COOKE,* ALEXIS M. MYCHAJLIW, JOHN SOUTHON, AND ROSS D. E. MacPHEE Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 1830 E Monument Street, Room 305A, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA (SBC) Department of Biology, Stanford University, 371 Serra Mall, Stanford, CA 94305, USA (AMM) Department of Earth System Science, University of California, Irvine, Croul Hall, Irvine, CA 92697, USA (JS) Department of Mammalogy, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA (RDEM) * Correspondent: [email protected] The Jamaican primate, Xenothrix mcgregori, regarded variously as either a pitheciid or a stem platyrrhine, was the terminal branch of a clade that likely entered the West Indies at least as early as the Early Miocene, although its lineage is represented by fossils of Quaternary age only. We present a new direct radiocarbon-based date of 1,477 ± 34 calibrated years before present (cal BP) for the last documented appearance of this species in the fossil record. We employed the Gaussian-resampled, inverse-weighted McInerny et al. (GRIWM) method to estimate the extinction date of X. mcgregori, based on the data presented here as well as 6 other dates derived from X. mcgregori sites. On this basis, we estimated a last occurrence ~900 BP. The cause or causes of this extinction, as well as the many others that occurred in late Quaternary of the Greater Antilles, remain a matter of debate. -

The Evolution of the Platyrrhine Talus: a Comparative Analysis of the Phenetic Affinities of the Miocene Platyrrhines with Their Modern Relatives

Journal of Human Evolution 111 (2017) 179e201 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol The evolution of the platyrrhine talus: A comparative analysis of the phenetic affinities of the Miocene platyrrhines with their modern relatives * Thomas A. Püschel a, , Justin T. Gladman b, c,Rene Bobe d, e, William I. Sellers a a School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom b Department of Anthropology, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, NY, USA c NYCEP, New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY, USA d Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile e Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, School of Anthropology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Platyrrhines are a diverse group of primates that presently occupy a broad range of tropical-equatorial Received 8 August 2016 environments in the Americas. However, most of the fossil platyrrhine species of the early Miocene Accepted 26 July 2017 have been found at middle and high latitudes. Although the fossil record of New World monkeys has Available online 29 August 2017 improved considerably over the past several years, it is still difficult to trace the origin of major modern clades. One of the most commonly preserved anatomical structures of early platyrrhines is the talus. Keywords: This work provides an analysis of the phenetic affinities of extant platyrrhine tali and their Miocene New World monkeys counterparts through geometric morphometrics and a series of phylogenetic comparative analyses. Talar morphology fi Geometric morphometrics Geometric morphometrics was used to quantify talar shape af nities, while locomotor mode per- Locomotor mode percentages centages (LMPs) were used to test if talar shape is associated with locomotion. -

First North American Fossil Monkey and Early Miocene Tropical Biotic Interchange Jonathan I

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature17415 First North American fossil monkey and early Miocene tropical biotic interchange Jonathan I. Bloch1, Emily D. Woodruff1,2, Aaron R. Wood1,3, Aldo F. Rincon1,4, Arianna R. Harrington1,2,5, Gary S. Morgan6, David A. Foster4, Camilo Montes7, Carlos A. Jaramillo8, Nathan A. Jud1, Douglas S. Jones1 & Bruce J. MacFadden1 New World monkeys (platyrrhines) are a diverse part of modern Primates Linnaeus, 1758 tropical ecosystems in North and South America, yet their early Anthropoidea Mivart, 1864 evolutionary history in the tropics is largely unknown. Molecular Platyrrhini Geoffroy, 1812 divergence estimates suggest that primates arrived in tropical Cebidae Bonaparte, 1831 Central America, the southern-most extent of the North American Panamacebus transitus gen. et sp. nov. landmass, with several dispersals from South America starting with the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama 3–4 million years Etymology. Generic name combines ‘Panama’ with ‘Cebus’, root taxon ago (Ma)1. The complete absence of primate fossils from Central for Cebidae. Specific name ‘transit’ (Latin, crossing) refers to its implied America has, however, limited our understanding of their history early Miocene dispersal between South and North America. in the New World. Here we present the first description of a fossil Holotype. UF 280128, left upper first molar (M1; Fig. 2a, b). monkey recovered from the North American landmass, the oldest Referred material. Left upper second molar (M2; UF 281001; Fig. 2a, b), known crown platyrrhine, from a precisely dated 20.9-Ma layer in partial left lower first incisor (I1; UF 280130), right lower second the Las Cascadas Formation in the Panama Canal Basin, Panama. -

New Platyrrhine Tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, Illinois 60115

Daniel L. Gebo New platyrrhine tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. U.S.A. Two new primate tali were discovered from the middle Miocene of South America at La Venta, Colombia. IGM-KU 8802 is similar in morphology to Callicebus and Aotus, and is allocated to cf. Aotus dindensis, while IGM-KU Marian Dagosto 8803, associated with a dentition of a new cebine primate, is similar to Saimiri. Both tali differ from the other known fossil platyrrhine tali, Departments of Cell, Molecular, and Dolichocebus and Cebupithecia, and increase our knowledge of the locomotor Structural Biology and Anthropology, diversity of the La Venta primate fauna. hrorthrerestern lJniuersi;v, Euanston, Illinois 60208, U.S.A. Alfred L. Rosenberger Department of Anthropology, L’niuersity of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60680, U.S.A. Takeshi Setoguchi Primate Research Institute, Kyoto C’niniuersiQ,Inuyama Cily, Aichi 484, Japan Received 18 April 1989 Revision received 4 December 1989and accepted 2 1 December 1989 Keywords: Platyrrhini, La Venta, foot bones, locomotion. Journal of Human Evolution (1990) 19,737-746 Introduction Two new platyrrhine tali were discovered at La Venta, Colombia, by the Japanese/American field team working in conjunction with INGEOMINAS (Instituto National de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras) during the field season of 1988. These two fossils add to the rare but growing number of postcranial remains of extinct platyrrhines from the Miocene of South America (Stirton, 1951; Gebo & Simons, 1987; Anapol & Fleagle, 1988; Ford, 1990). They represent the first new primate postcranials to be described from La Venta in nearly four decades. -

New Primate Genus from the Miocene of Argentina

New primate genus from the Miocene of Argentina Marcelo F. Tejedor*†, Ada´ n A. Tauber‡, Alfred L. Rosenberger§¶, Carl C. Swisher IIIʈ, and Marı´aE. Palacios** *Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı´ficasy Te´cnicas, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolucio´n y Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Esquel, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘‘San Juan Bosco,’’ Sarmiento 849, 9200 Esquel, Argentina; ‡Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Fı´sicasy Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Avenida Velez Sarsfield 249, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina; §Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210; ¶Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 11024; ʈDepartment of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854; and **Museo Regional Provincial ‘‘Padre Manuel Jesu´s Molina,’’ Ramo´n y Cajal 51, 9400 Rı´oGallegos, Argentina Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved December 28, 2005 (received for review August 4, 2005) Killikaike blakei is a new genus and species of anthropoid from the of the estuary of the Rio Gallegos river. The stratigraphy is late Early Miocene of southeastern Argentina based on the most divided into two members (6): Estancia La Costa (120 m thick pristine fossil platyrrhine skull and dentition known so far. It is part with 18 fossiliferous levels) and Estancia Angelina (103 m thick of the New World platyrrhine clade (Family Cebidae; Subfamily with four fossiliferous levels). There are two types of volcanic ash Cebinae) including modern squirrel (Saimiri) and capuchin mon- at the locality. -

Comparative Biogeography of Neotropical Primates Molecular

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Review Special issue: Comparative biogeography of Neotropical primates ⇑ Jessica W. Lynch Alfaro a,b, , Liliana Cortés-Ortiz c, Anthony Di Fiore d, Jean P. Boubli e,f a Institute for Society and Genetics, 1321 Rolfe Hall, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA c Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA d Department of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin, USA e School of Environment and Life Sciences, 315 Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford M5 4WT, UK f Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia INPA, Manaus, Brazil article info abstract Article history: New research presented in this special issue of Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution on the ‘‘Phylogeny Received 29 July 2014 and Biogeography of Neotropical Primates’’ greatly improves our understanding of the evolutionary his- Revised 20 September 2014 tory of the New World monkeys and provides insights into the multiple platyrrhine radiations, diversi- Accepted 30 September 2014 fications, extinctions, and recolonizations that have taken place over time and over space in the Available online xxxx Neotropics. Here, we synthesize genetic and biogeographic research from the past several years to con- struct an overarching hypothesis for -

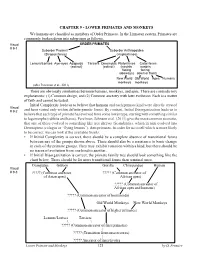

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES AND MONKEYS We humans are classified as members of Order Primates. In the Linnaean system, Primates are commonly broken down into subgroups as follows. Visual ORDER PRIMATES # 9-1 Suborder Prosimii Suborder Anthropoidea (Strepsirrhines) (Haplorrhines) Lemurs/Lorises Aye-ayes Adapoids Tarsiers Omomyids Platyrrhines Catarrhines (extinct) (extinct) (nostrils nostrils facing facing sideways) down or front) New World Old World Apes Humans monkeys monkeys (after Perelman et al., 2011) There are obviously similarities between humans, monkeys, and apes. There are contradictory explanations: (1) Common design, and (2) Common ancestry with later evolution. Each is a matter of faith and cannot be tested. Initial Complexity leads us to believe that humans and each primate kind were directly created Visual # 9-2 and have varied only within definite genetic limits. By contrast, Initial Disorganization leads us to believe that each type of primate has evolved from some lower type, starting with something similar to lagomorphs (rabbits and hares). Perelman, Johnson et al. (2011) give the most common scenario, that one of these evolved to something like tree shrews (Scandentia), which in turn evolved into Dermoptera (colugos or “flying lemurs”), then primates. In order for us to tell which is more likely to be correct, we can look at the available fossils. • If Initial Complexity is correct, there should be a complete absence of transitional forms between any of the groups shown above. There should also be a resistance to basic change in each of the primate groups. They may exhibit variation within a kind, but there should be no traces of evolution from one kind to another. -

Figure S1. Schematic Maximum-Likelihood Tree of Ucp Sequences Used in This Study (N=400)

Figure S1. Schematic maximum-likelihood tree of ucp sequences used in this study (N=400). Branch lengths denote number of substitutions per site. Exon 1 1 10 20 30 40 50 |...|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....| Homo sapiens ATGGGGGGCCTGA-CAGCCTCGGACGTACACCCGACCC---TGGGGGTCC Bradypus variegatus ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Choloepus hoffmanni ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Mylodon darwinii ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Cyclopes didactylus ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Dasypus novemcinctus ATGGGGCGCCAGGGCTCCCGCGGGCTCACCCCCCGC-------------- Procavia capensis CTG--AGTTAAGA-CAACCTCAGAAATGCCGCCTAC-----------GCA Elephas maximus ACGGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Mammuthus primigenius ACGGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Loxodonta africana ACCGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Trichechus manatus ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTGGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Dugong dugon ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTCGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Hydrodamalis gigas ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTCGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Sus scrofa CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCCCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Sus verrucosus CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCTCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Sus cebifrons CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCTCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Physeter macrocephalus ATGGTGGGACTCG-CAGCCTCATACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA Delphinapterus leucas -------------------------------------------------- Lipotes vexillifer ATGGTGGGACTCG-CAGCCTCAGACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA Balaena mysticetus ATGGTGGCACTCA-CAGCCTCAGACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA