CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming

Distribution and Stratigraphip Correlation of Upper:UB_ • Ju Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming U,S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESS IONAL PAPER 1540 Cover. A member of the American Museum of Natural History 1896 expedition enter ing the badlands of the Willwood Formation on Dorsey Creek, Wyoming, near what is now U.S. Geological Survey fossil vertebrate locality D1691 (Wardel Reservoir quadran gle). View to the southwest. Photograph by Walter Granger, courtesy of the Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York, negative no. 35957. DISTRIBUTION AND STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION OF UPPER PALEOCENE AND LOWER EOCENE FOSSIL MAMMAL AND PLANT LOCALITIES OF THE FORT UNION, WILLWOOD, AND TATMAN FORMATIONS, SOUTHERN BIGHORN BASIN, WYOMING Upper part of the Will wood Formation on East Ridge, Middle Fork of Fifteenmile Creek, southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. The Kirwin intrusive complex of the Absaroka Range is in the background. View to the west. Distribution and Stratigraphic Correlation of Upper Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Tatman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming By Thomas M. Down, Kenneth D. Rose, Elwyn L. Simons, and Scott L. Wing U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1540 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Robert M. Hirsch, Acting Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Calcaneal Proportions in Primates and Locomotor Inferences in Anchomomys and Other Palaeogene Euprimates

Swiss J Palaeontol (2012) 131:147–159 DOI 10.1007/s13358-011-0032-5 Calcaneal proportions in primates and locomotor inferences in Anchomomys and other Palaeogene Euprimates Salvador Moya`-Sola` • Meike Ko¨hler • David M. Alba • Imma Roig Received: 3 October 2011 / Accepted: 21 November 2011 / Published online: 8 December 2011 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2011 Abstract Foot proportions, and in particular the length- inferred only when anterior calcaneal length departs from ening of the tarsal elements, play a fundamental role in the the scaling of non-specialized primate groups. The role of discussion on the locomotor adaptations of Palaeogene leaping on the inferred locomotor repertoire of earliest primates. The elongation of the distal portion of the tarsus, primates needs to be revised considering the results of this particularly the anterior part of the calcaneus, is frequently work. interpreted as an adaptation to leaping and has played a fundamental role in the reconstruction of the locomotor Keywords Fossil and extant primates Á Foot Á adaptations of the earliest primates. Here, we report an Calcaneal proportions Á Allometry Á Grasping Á allometric analysis of calcaneal proportions in primates and Leaping Á Anchomomys other mammals, in order to determine the actual differ- ences in calcaneal proportions. This analysis reveals that primates as a group display a relatively longer distal cal- Introduction caneus, relative to both total calcaneal length and body mass, when compared with other mammals. Contrary to The origin of primates of modern aspect (euprimates) was current expectations, morphofunctional analysis indicates characterized by a profound reorganization of the post- that a moderate degree of calcaneal elongation is not an cranial anatomy apparently related to arboreal locomotion adaptation to leaping, but it is merely a compensatory (Dagosto 1988). -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

Evidence for a Convergent Slowdown in Primate Molecular Rates and Its Implications for the Timing of Early Primate Evolution

Evidence for a convergent slowdown in primate molecular rates and its implications for the timing of early primate evolution Michael E. Steipera,b,c,d,1 and Erik R. Seifferte aDepartment of Anthropology, Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY 10065; Programs in bAnthropology and cBiology, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, NY 10016; dNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY; and eDepartment of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8081 Edited by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved February 28, 2012 (received for review November 29, 2011) A long-standing problem in primate evolution is the discord divergences—that molecular rates were exceptionally rapid in between paleontological and molecular clock estimates for the the earliest primates, and that these rates have convergently time of crown primate origins: the earliest crown primate fossils slowed over the course of primate evolution. Indeed, a conver- are ∼56 million y (Ma) old, whereas molecular estimates for the gent rate slowdown has been suggested as an explanation for the haplorhine-strepsirrhine split are often deep in the Late Creta- large differences between the molecular and fossil evidence for ceous. One explanation for this phenomenon is that crown pri- the timing of placental mammalian evolution generally (18, 19). mates existed in the Cretaceous but that their fossil remains However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested within have not yet been found. Here we provide strong evidence that a particular mammalian group. this discordance is better-explained by a convergent molecular Here we test this “convergent rate slowdown” hypothesis in rate slowdown in early primate evolution. -

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

Fossil Primates

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 16 www.accessscience.com Fossil primates Contributed by: Eric Delson Publication year: 2014 Extinct members of the order of mammals to which humans belong. All current classifications divide the living primates into two major groups (suborders): the Strepsirhini or “lower” primates (lemurs, lorises, and bushbabies) and the Haplorhini or “higher” primates [tarsiers and anthropoids (New and Old World monkeys, greater and lesser apes, and humans)]. Some fossil groups (omomyiforms and adapiforms) can be placed with or near these two extant groupings; however, there is contention whether the Plesiadapiformes represent the earliest relatives of primates and are best placed within the order (as here) or outside it. See also: FOSSIL; MAMMALIA; PHYLOGENY; PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY; PRIMATES. Vast evidence suggests that the order Primates is a monophyletic group, that is, the primates have a common genetic origin. Although several peculiarities of the primate bauplan (body plan) appear to be inherited from an inferred common ancestor, it seems that the order as a whole is characterized by showing a variety of parallel adaptations in different groups to a predominantly arboreal lifestyle, including anatomical and behavioral complexes related to improved grasping and manipulative capacities, a variety of locomotor styles, and enlargement of the higher centers of the brain. Among the extant primates, the lower primates more closely resemble forms that evolved relatively early in the history of the order, whereas the higher primates represent a group that evolved more recently (Fig. 1). A classification of the primates, as accepted here, appears above. Early primates The earliest primates are placed in their own semiorder, Plesiadapiformes (as contrasted with the semiorder Euprimates for all living forms), because they have no direct evolutionary links with, and bear few adaptive resemblances to, any group of living primates. -

Early Eocene Primates from Gujarat, India

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Human Evolution xxx (2009) 1–39 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Early Eocene Primates from Gujarat, India Kenneth D. Rose a,*, Rajendra S. Rana b, Ashok Sahni c, Kishor Kumar d, Pieter Missiaen e, Lachham Singh b, Thierry Smith f a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA b H.N.B. Garhwal University, Srinagar 246175, Uttarakhand, India c Panjab University, Chandigarh 160014, India d Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun 248001, Uttarakhand, India e University of Ghent, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium f Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium article info abstract Article history: The oldest euprimates known from India come from the Early Eocene Cambay Formation at Vastan Mine Received 24 June 2008 in Gujarat. An Ypresian (early Cuisian) age of w53 Ma (based on foraminifera) indicates that these Accepted 8 January 2009 primates were roughly contemporary with, or perhaps predated, the India-Asia collision. Here we present new euprimate fossils from Vastan Mine, including teeth, jaws, and referred postcrania of the Keywords: adapoids Marcgodinotius indicus and Asiadapis cambayensis. They are placed in the new subfamily Eocene Asiadapinae (family Notharctidae), which is most similar to primitive European Cercamoniinae such as India Donrussellia and Protoadapis. Asiadapines were small primates in the size range of extant smaller Notharctidae Adapoidea bushbabies. Despite their generally very plesiomorphic morphology, asiadapines also share a few derived Omomyidae dental traits with sivaladapids, suggesting a possible relationship to these endemic Asian adapoids. In Eosimiidae addition to the adapoids, a new species of the omomyid Vastanomys is described. -

The Evolution of the Platyrrhine Talus: a Comparative Analysis of the Phenetic Affinities of the Miocene Platyrrhines with Their Modern Relatives

Journal of Human Evolution 111 (2017) 179e201 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol The evolution of the platyrrhine talus: A comparative analysis of the phenetic affinities of the Miocene platyrrhines with their modern relatives * Thomas A. Püschel a, , Justin T. Gladman b, c,Rene Bobe d, e, William I. Sellers a a School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom b Department of Anthropology, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, NY, USA c NYCEP, New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY, USA d Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile e Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, School of Anthropology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Platyrrhines are a diverse group of primates that presently occupy a broad range of tropical-equatorial Received 8 August 2016 environments in the Americas. However, most of the fossil platyrrhine species of the early Miocene Accepted 26 July 2017 have been found at middle and high latitudes. Although the fossil record of New World monkeys has Available online 29 August 2017 improved considerably over the past several years, it is still difficult to trace the origin of major modern clades. One of the most commonly preserved anatomical structures of early platyrrhines is the talus. Keywords: This work provides an analysis of the phenetic affinities of extant platyrrhine tali and their Miocene New World monkeys counterparts through geometric morphometrics and a series of phylogenetic comparative analyses. Talar morphology fi Geometric morphometrics Geometric morphometrics was used to quantify talar shape af nities, while locomotor mode per- Locomotor mode percentages centages (LMPs) were used to test if talar shape is associated with locomotion. -

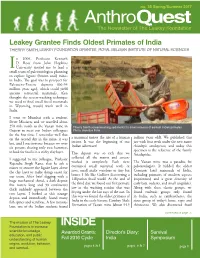

Anthroquest the Newsletter of the Leakey Foundation

no. 35 Spring/Summer 2017 AnthroQuest The Newsletter of The Leakey Foundation Leakey Grantee Finds Oldest Primates of India THIERRY SMITH, LEAKEY FOUNDATION GRANTEE, ROYAL BELGIAN INSTITUTE OF NATURAL SCIENCES n 2004, Professor Kenneth D. Rose from John Hopkins I University invited me to lead a small team of paleontologists planning to explore lignite (brown coal) mines in India. The goal was to prospect for Paleocene-Eocene deposits (66-34 million years ago), which could yield ancient terrestrial mammals. Ken thought the screen-washing technique we used to find small fossil mammals in Wyoming would work well in India. I went to Mumbai with a student, Pieter Missiaen, and we travelled about 250 mile north to the Vastan mine in Thierry Smith screenwashing sediments for small remains of earliest Indian primates Gujarat to meet our Indian colleagues Photo: Annelise Folie for the first time. I remember well that on the second day in the mine, it was a mammal incisor the size of a human million years old). We published this hot, and I was nervous because we were incisor. It was the beginning of our jaw with four teeth under the new name six persons sharing only two hammers Indian adventure! Asiadapis cambayensis, and today this to look for fossils in a sticky clay layer. specimen is the reference of the family This deposit was so rich that we Asiadapidae. I suggested to my colleague, Professor collected all the matrix and screen- Rajendra Singh Rana, that he ask a washed it completely. Each sieve The Vastan mine was a paradise for miner to remove the lignite layer above contained small mammal teeth or paleontologists.