This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Platyrrhine Tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, Illinois 60115

Daniel L. Gebo New platyrrhine tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. U.S.A. Two new primate tali were discovered from the middle Miocene of South America at La Venta, Colombia. IGM-KU 8802 is similar in morphology to Callicebus and Aotus, and is allocated to cf. Aotus dindensis, while IGM-KU Marian Dagosto 8803, associated with a dentition of a new cebine primate, is similar to Saimiri. Both tali differ from the other known fossil platyrrhine tali, Departments of Cell, Molecular, and Dolichocebus and Cebupithecia, and increase our knowledge of the locomotor Structural Biology and Anthropology, diversity of the La Venta primate fauna. hrorthrerestern lJniuersi;v, Euanston, Illinois 60208, U.S.A. Alfred L. Rosenberger Department of Anthropology, L’niuersity of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60680, U.S.A. Takeshi Setoguchi Primate Research Institute, Kyoto C’niniuersiQ,Inuyama Cily, Aichi 484, Japan Received 18 April 1989 Revision received 4 December 1989and accepted 2 1 December 1989 Keywords: Platyrrhini, La Venta, foot bones, locomotion. Journal of Human Evolution (1990) 19,737-746 Introduction Two new platyrrhine tali were discovered at La Venta, Colombia, by the Japanese/American field team working in conjunction with INGEOMINAS (Instituto National de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras) during the field season of 1988. These two fossils add to the rare but growing number of postcranial remains of extinct platyrrhines from the Miocene of South America (Stirton, 1951; Gebo & Simons, 1987; Anapol & Fleagle, 1988; Ford, 1990). They represent the first new primate postcranials to be described from La Venta in nearly four decades. -

New Primate Genus from the Miocene of Argentina

New primate genus from the Miocene of Argentina Marcelo F. Tejedor*†, Ada´ n A. Tauber‡, Alfred L. Rosenberger§¶, Carl C. Swisher IIIʈ, and Marı´aE. Palacios** *Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı´ficasy Te´cnicas, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolucio´n y Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Esquel, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘‘San Juan Bosco,’’ Sarmiento 849, 9200 Esquel, Argentina; ‡Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Fı´sicasy Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Avenida Velez Sarsfield 249, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina; §Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210; ¶Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 11024; ʈDepartment of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854; and **Museo Regional Provincial ‘‘Padre Manuel Jesu´s Molina,’’ Ramo´n y Cajal 51, 9400 Rı´oGallegos, Argentina Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved December 28, 2005 (received for review August 4, 2005) Killikaike blakei is a new genus and species of anthropoid from the of the estuary of the Rio Gallegos river. The stratigraphy is late Early Miocene of southeastern Argentina based on the most divided into two members (6): Estancia La Costa (120 m thick pristine fossil platyrrhine skull and dentition known so far. It is part with 18 fossiliferous levels) and Estancia Angelina (103 m thick of the New World platyrrhine clade (Family Cebidae; Subfamily with four fossiliferous levels). There are two types of volcanic ash Cebinae) including modern squirrel (Saimiri) and capuchin mon- at the locality. -

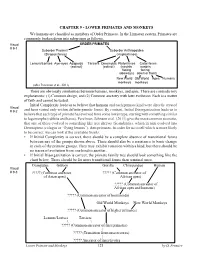

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES AND MONKEYS We humans are classified as members of Order Primates. In the Linnaean system, Primates are commonly broken down into subgroups as follows. Visual ORDER PRIMATES # 9-1 Suborder Prosimii Suborder Anthropoidea (Strepsirrhines) (Haplorrhines) Lemurs/Lorises Aye-ayes Adapoids Tarsiers Omomyids Platyrrhines Catarrhines (extinct) (extinct) (nostrils nostrils facing facing sideways) down or front) New World Old World Apes Humans monkeys monkeys (after Perelman et al., 2011) There are obviously similarities between humans, monkeys, and apes. There are contradictory explanations: (1) Common design, and (2) Common ancestry with later evolution. Each is a matter of faith and cannot be tested. Initial Complexity leads us to believe that humans and each primate kind were directly created Visual # 9-2 and have varied only within definite genetic limits. By contrast, Initial Disorganization leads us to believe that each type of primate has evolved from some lower type, starting with something similar to lagomorphs (rabbits and hares). Perelman, Johnson et al. (2011) give the most common scenario, that one of these evolved to something like tree shrews (Scandentia), which in turn evolved into Dermoptera (colugos or “flying lemurs”), then primates. In order for us to tell which is more likely to be correct, we can look at the available fossils. • If Initial Complexity is correct, there should be a complete absence of transitional forms between any of the groups shown above. There should also be a resistance to basic change in each of the primate groups. They may exhibit variation within a kind, but there should be no traces of evolution from one kind to another. -

Figure S1. Schematic Maximum-Likelihood Tree of Ucp Sequences Used in This Study (N=400)

Figure S1. Schematic maximum-likelihood tree of ucp sequences used in this study (N=400). Branch lengths denote number of substitutions per site. Exon 1 1 10 20 30 40 50 |...|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....| Homo sapiens ATGGGGGGCCTGA-CAGCCTCGGACGTACACCCGACCC---TGGGGGTCC Bradypus variegatus ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Choloepus hoffmanni ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Mylodon darwinii ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Cyclopes didactylus ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? Dasypus novemcinctus ATGGGGCGCCAGGGCTCCCGCGGGCTCACCCCCCGC-------------- Procavia capensis CTG--AGTTAAGA-CAACCTCAGAAATGCCGCCTAC-----------GCA Elephas maximus ACGGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Mammuthus primigenius ACGGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Loxodonta africana ACCGTAGGCCAGA-CGACCGCAGACGTGCCCCGGACCATGGTGGGGGTCA Trichechus manatus ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTGGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Dugong dugon ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTCGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Hydrodamalis gigas ATGGTGGGCCAGA-CTACCTCGGATGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGGCGTCA Sus scrofa CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCCCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Sus verrucosus CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCTCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Sus cebifrons CTGTCAGGA-TGA-CAGTTCCTGAAGTGCCCTCGACCA---TAGCGGTCA Physeter macrocephalus ATGGTGGGACTCG-CAGCCTCATACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA Delphinapterus leucas -------------------------------------------------- Lipotes vexillifer ATGGTGGGACTCG-CAGCCTCAGACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA Balaena mysticetus ATGGTGGCACTCA-CAGCCTCAGACGTGCCCCCGACCA---TGGCGGTCA -

Centromere Repositioning in Mammals

Heredity (2012) 108, 59–67 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/12 www.nature.com/hdy REVIEW Centromere repositioning in mammals M Rocchi1, N Archidiacono1, W Schempp2, O Capozzi1 and R Stanyon3 The evolutionary history of chromosomes can be tracked by the comparative hybridization of large panels of bacterial artificial chromosome clones. This approach has disclosed an unprecedented phenomenon: ‘centromere repositioning’, that is, the movement of the centromere along the chromosome without marker order variation. The occurrence of evolutionary new centromeres (ENCs) is relatively frequent. In macaque, for instance, 9 out of 20 autosomal centromeres are evolutionarily new; in donkey at least 5 such neocentromeres originated after divergence from the zebra, in less than 1 million years. Recently, orangutan chromosome 9, considered to be heterozygous for a complex rearrangement, was discovered to be an ENC. In humans, in addition to neocentromeres that arise in acentric fragments and result in clinical phenotypes, 8 centromere- repositioning events have been reported. These ‘real-time’ repositioned centromere-seeding events provide clues to ENC birth and progression. In the present paper, we provide a review of the centromere repositioning. We add new data on the population genetics of the ENC of the orangutan, and describe for the first time an ENC on the X chromosome of squirrel monkeys. Next-generation sequencing technologies have started an unprecedented, flourishing period of rapid whole-genome sequencing. In this context, it is worth noting that these technologies, uncoupled from cytogenetics, would miss all the biological data on evolutionary centromere repositioning. Therefore, we can anticipate that classical and molecular cytogenetics will continue to have a crucial role in the identification of centromere movements. -

30 Tejedor.Pmd

Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, v.66, n.1, p.251-269, jan./mar.2008 ISSN 0365-4508 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEOTROPICAL PRIMATES 1 (With 4 figures) MARCELO F. TEJEDOR 2 ABSTRACT: A significant event in the early evolution of Primates is the origin and radiation of anthropoids, with records in North Africa and Asia. The New World Primates, Infraorder Platyrrhini, have probably originated among these earliest anthropoids morphologically and temporally previous to the catarrhine/platyrrhine branching. The platyrrhine fossil record comes from distant regions in the Neotropics. The oldest are from the late Oligocene of Bolivia, with difficult taxonomic attribution. The two richest fossiliferous sites are located in the middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and to the south in early to middle Miocene sites from the Argentine Patagonia and Chile. The absolute ages of these sedimentary deposits are ranging from 12 to 20 Ma, the oldest in Patagonia and Chile. These northern and southern regions have a remarkable taxonomic diversity and several extinct taxa certainly represent living clades. In addition, in younger sediments ranging from late Miocene through Pleistocene, three genera have been described for the Greater Antilles, two genera in eastern Brazil, and at least three forms for Río Acre. In general, the fossil record of South American primates sheds light on the old radiations of the Pitheciinae, Cebinae, and Atelinae. However, several taxa are still controversial. Key words: Neotropical Primates. Origin. Evolution. RESUMO: Origem e evolução dos primatas neotropicais. Um evento significativo durante o início da evolução dos primatas é a origem e a radiação dos antropóides, com registros no norte da África e da Ásia. -

Stem Taxa, Homoplasy, Long Lineages, and the Phylogenetic Position of Dolichocebus

Journal of Human Evolution 59 (2010) 218e222 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol News and Views Stem taxa, homoplasy, long lineages, and the phylogenetic position of Dolichocebus Richard F. Kay a,*, John G. Fleagle b a Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA b Department of Anatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794-8081, USA article info identifying them as being members of a clade. In our analysis, a suite of derived anatomical features that are generally lacking in Article history: the Patagonian taxa unites all living, or crown, platyrrhines. Among Received 16 November 2009 other things, compared with the Patagonian taxa, crown platyr- Accepted 12 February 2010 rhines have a shorter rostrum, a more transversely arched palate, Keywords: more convergent orbits, reorganization of the arrangement of the Platyrrhini bones at pterion, larger, more transversely positioned premolar Phylogenetics metaconids, loss of molar hypoconulids and of a postentoconid Anthropoidea sulcus, and reduction of molar roots. It is the absence of the above- Molecular clocks listed derived features of crown platyrrhines in the Patagonian taxa that suggests each of them is a stem platyrrhine, and outside of the modern radiation. The Patagonian taxa may belong to a separate stem clade or they may be a paraphyletic group, one species of which may prove to be the sister to the most recent common In his reply to our recent paper (Kay et al., 2008) entitled “The ancestor of living platyrrhines. Either way, Dolichocebus, Trem- anatomy of Dolichocebus gaimanensis, a stem platyrrhine monkey acebus and the other less-well known Patagonian early Miocene from Argentina,” Rosenberger (2010: p.1) addresses a wide range of monkeys are stem platyrrhines. -

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82 (2015) 358–374

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82 (2015) 358–374 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Biogeography in deep time – What do phylogenetics, geology, and paleoclimate tell us about early platyrrhine evolution? Richard F. Kay Department of Evolutionary Anthropology & Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Duke University, Box 90383, Durham, NC 27708, United States article info abstract Article history: Molecular data have converged on a consensus about the genus-level phylogeny of extant platyrrhine Available online 12 December 2013 monkeys, but for most extinct taxa and certainly for those older than the Pleistocene we must rely upon morphological evidence from fossils. This raises the question as to how well anatomical data mirror Keywords: molecular phylogenies and how best to deal with discrepancies between the molecular and morpholog- Platyrrhini ical data as we seek to extend our phylogenies to the placement of fossil taxa. Oligocene Here I present parsimony-based phylogenetic analyses of extant and fossil platyrrhines based on an Miocene anatomical dataset of 399 dental characters and osteological features of the cranium and postcranium. South America I sample 16 extant taxa (one from each platyrrhine genus) and 20 extinct taxa of platyrrhines. The tree Paraná Portal Anthropoidea structure is constrained with a ‘‘molecular scaffold’’ of extant species as implemented in maximum par- simony using PAUP with the molecular-based ‘backbone’ approach. The data set encompasses most of the known extinct species of platyrrhines, ranging in age from latest Oligocene ( 26 Ma) to the Recent. The tree is rooted with extant catarrhines, and Late Eocene and Early Oligocene African anthropoids. -

Alfred L. Rosenberger Fossil New World Monkeys Dispute the Molecular Clock

Alfred L. Fossil New World Monkeys Dispute the Rosenberger Molecular Clock Department of Anthropology, New World monkeys offer an empirical test of the accuracy of molecular University of Illinois at Chicago, clocks. A phylogenetic reconstruction based upon craniodental morphology Chicago, Illinois 60680, U.S.A. suggests that platyrrhine clades and generic lineages are far older than Received 16 August 1984 and albumin and transferrin "clocks" indicated. It is uniustitied to accept the accepted 21 August 1984 molecular clock's timescale when protein and morphological evidence do not generate symmetrical cladograms. Such a dichotomy in evidence for Keyword~: phylogeny, New World anthropoids exists and, by implication, casts doubt upon systematics, platyrrhines, [bssils, molecular divergence dates of Old World monkeys, apes and hominids. molecular clock. Ever since it was first introduced by Sarich & Wilson (1967), the molecular clock of primate evolution, which projects the divergence times of living lineages based upon their immunological differences, has received criticism from various disciplines (e.g., Lovejoy el al., 1972; Read, 1975; Korey, 1981; Goodman, 1976). Because paleontology offers the most direct empirical test of such historical hypotheses, the molecular clock's timing of adaptive radiations has been independently checked against the fossil record of hominoid apes and hominids (Simons, 1976; Uzzel & Pilbeam, 1971; Walker, 1976), cercopithecine Old World monkeys (Cronin & Meikle, 1982) and the broad outlines of Cenozoic primate evolution (Romero-Herra et al., 1978). Although the consensus once claimed that tile albumin-transferrin clock seriously underestimated divergence dates, a rethinking of hominoid evolution during the past few years has forced a turnabout among paleoanthropologists. -

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

LABORATORY PRIMATE NEWSLETTER Vol. 48, No. 3 July 2009 JUDITH E. SCHRIER, EDITOR JAMES S. HARPER, GORDON J. HANKINSON AND LARRY HULSEBOS, ASSOCIATE EDITORS MORRIS L. POVAR AND JASON MACHAN, CONSULTING EDITORS ELVA MATHIESEN, ASSISTANT EDITOR ALLAN M. SCHRIER, FOUNDING EDITOR, 1962-1987 Published Quarterly by the Schrier Research Laboratory Psychology Department, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island ISSN 0023-6861 POLICY STATEMENT The Laboratory Primate Newsletter provides a central source of information about nonhuman primates and related matters to scientists who use these animals in their research and those whose work supports such research. The Newsletter (1) provides information on care and breeding of nonhuman primates for laboratory research, (2) disseminates general information and news about the world of primate research (such as announcements of meetings, research projects, sources of information, nomenclature changes), (3) helps meet the special research needs of individual investigators by publishing requests for research material or for information related to specific research problems, and (4) serves the cause of conservation of nonhuman primates by publishing information on that topic. As a rule, research articles or summaries accepted for the Newsletter have some practical implications or provide general information likely to be of interest to investigators in a variety of areas of primate research. However, special consideration will be given to articles containing data on primates not conveniently publishable elsewhere. General descriptions of current research projects on primates will also be welcome. The Newsletter appears quarterly and is intended primarily for persons doing research with nonhuman primates. Back issues may be purchased for $10.00 each. We are no longer printing paper issues, except those we will send to subscribers who have paid in advance. -

New Eocene Primate from Myanmar Shares Dental Characters with African Eocene Crown Anthropoids

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11295-6 OPEN New Eocene primate from Myanmar shares dental characters with African Eocene crown anthropoids Jean-Jacques Jaeger1, Olivier Chavasseau 1, Vincent Lazzari1, Aung Naing Soe2, Chit Sein 3, Anne Le Maître 1,4, Hla Shwe5 & Yaowalak Chaimanee1 Recent discoveries of older and phylogenetically more primitive basal anthropoids in China and Myanmar, the eosimiiforms, support the hypothesis that Asia was the place of origins of 1234567890():,; anthropoids, rather than Africa. Similar taxa of eosimiiforms have been discovered in the late middle Eocene of Myanmar and North Africa, reflecting a colonization event that occurred during the middle Eocene. However, these eosimiiforms were probably not the closest ancestors of the African crown anthropoids. Here we describe a new primate from the middle Eocene of Myanmar that documents a new clade of Asian anthropoids. It possesses several dental characters found only among the African crown anthropoids and their nearest rela- tives, indicating that several of these characters have appeared within Asian clades before being recorded in Africa. This reinforces the hypothesis that the African colonization of anthropoids was the result of several dispersal events, and that it involved more derived taxa than eosimiiforms. 1 Laboratory PALEVOPRIM, UMR CNRS 7262, University of Poitiers, 6 rue Michel Brunet Cedex 9, 86073 Poitiers, France. 2 University of Distance Education, Mandalay 05023, Myanmar. 3 Ministry of Education, Department of Higher Education, Naypyitaw 15011, Myanmar. 4 Department of Theoretical Biology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria. 5 Department of Archaeology and National Museum, Mandalay Branch, Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, Mandalay 05011, Myanmar. -

Evolutionary History of New World Monkeys Revealed by Molecular and Fossil Data

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/178111; this version posted August 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data Daniele Silvestro1,2,3,*, Marcelo F. Tejedor4,5,*, Martha L. Serrano-Serrano2, Oriane Loiseau2, Victor Rossier2, Jonathan Rolland2, Alexander Zizka1,3, Alexandre Antonelli1,3,6, Nicolas Salamin2 1 Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 413 19 Gothenburg, Sweden 2 Department of Computational Biology, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Center, Gothenburg, Sweden 4 CONICET, Centro Nacional Patagonico, Boulevard Almirante Brown 2915, 9120 Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. 5 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Trelew, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘San Juan Bosco’, 9100 Trelew, Chubut, Argentina. 6 Gothenburg Botanical Garden, Carl Skottsbergs gata 22A, 413 19 Gothenburg, Sweden * Equal contributions 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/178111; this version posted August 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract New World monkeys (parvorder Platyrrhini) are one of the most diverse groups of primates, occupying today a wide range of ecosystems in the American tropics and exhibiting large variations in ecology, morphology, and behavior. Although the relationships among the almost 200 living species are relatively well understood, we lack robust estimates of the timing of origin, the ancestral morphology, and the evolution of the distribution of the clade.