Inferred from Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

Common Squirrel Monkey Scientific Name: Saimiri Sciureus

Common Squirrel Monkey Scientific Name: Saimiri sciureus Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Cebidae The head and body length is 10.4 to 14.4 in.; tail length is 14 to 17 in; and weight is 2.5 to 3.7 lb. The tail is not prehensile. These diurnal monkeys are arboreal and only occasionally descend to the ground. Movement is quadrupedal with relatively little leaping. Ranges are often ill-defined and troops may number into the 40-50 range. During the mating season males establish a dominance hierarchy through fierce fighting with the higher-ranking individuals then interacting with the females. The females establish a dominance hierarchy during pregnancy. After the birth of the young, females exclude the males. The newborn cling to their mothers back for the first few weeks of life. Independence is achieved at 1 year. Range East of the Andes from Colombia and northern Peru to north- eastern Brazil Habitat Primary and secondary forests, cultivated areas, usually along streams Gestation 152-172 days Litter 1 Behavior These diurnal monkeys are arboreal and only occasionally descend to the ground. Movement is quadrupedal with relatively little leaping. Wild troops are most active from early to mid-morning and mid- to late afternoon, usually resting an hour or two at midday. Ranges are often ill-defined, and troops may number into the 40-50 range. Groups are known to split during the day into subgroups of pregnant females, females with young and adult males. Reproduction During the mating season males establish a dominance hierarchy through fierce fighting with the higher-ranking individuals then interacting with the females. -

Saimiri Sciureus) by an Amazon Tree Boa (Corallus Hortulanus

Predation of a squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) by an Amazon tree boa (Corallus hortulanus): even small boids may be a potential threat to small-bodied platyrrhines Marco Antônio Ribeiro-Júnior, Stephen Francis Ferrari, Janaina Reis Ferreira Lima, Claudia Regina da Silva & Jucivaldo Dias Lima Primates ISSN 0032-8332 Primates DOI 10.1007/s10329-016-0545-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Primates DOI 10.1007/s10329-016-0545-z NEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Predation of a squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) by an Amazon tree boa (Corallus hortulanus): even small boids may be a potential threat to small-bodied platyrrhines 1 2,3 4,5 Marco Antoˆnio Ribeiro-Ju´nior • Stephen Francis Ferrari • Janaina Reis Ferreira Lima • 5 4,5 Claudia Regina da Silva • Jucivaldo Dias Lima Received: 19 April 2016 / Accepted: 29 April 2016 Ó Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan 2016 Abstract Predation has been suggested to play a major capable of capturing an agile monkey like Saimiri, C. -

Squirrel Monkeys and Space Motion Sickness

Japanese Journal of Physiology, 52, 1–20, 2002 REVIEW Squirrel Monkeys and Space Motion Sickness Kenichi MATSUNAMI Science and Technology Promotion Center, Kakamigahara, 509–0108 Japan Abstract: Studies of the vestibular system in system is crucially important in the genesis of squirrel monkeys in consideration of space mo- SMS (SAS). In this connection, the ablation stud- tion sickness (SMS) or space adaptation syn- ies of labyrinth, semicircular canals, and other drome (SAS) were reviewed. First, the phyloge- SAS-related areas were referred to, and consid- netic position of the squirrel monkey was consid- eration was made for experiments about caloric ered. Then the anatomico-physiological studies irrigation of the ear. A hypothetic model was then of both the peripheral and the central vestibular proposed for the genesis of SAS. [Japanese systems were described, because the vestibular Journal of Physiology, 52, 1–20, 2002] Key words: squirrel monkey, vestibular system, cerebral cortex, space motion sickness (SMS), space adaptation syndromes (SAS). The construction of the new space station will be contamination of fatal B virus for human subjects; (4) completed soon, and many experiments will be under- They are relatively free from dysentery or tuberculo- taken. Many Japanese scientists will join in these new sis; (5) They are less dangerous because of their small experiments. Animal experiments are expected to size. On the other hand, (1) They are small and weak, solve problems in space physiology. Several kinds of thus vulnerable to bleeding during surgery; (2) The nonhuman primates such as the chimpanzee (Pan bone of the skull is thin, and it is difficult to perma- troglodytes), common squirrel monkey (Saimiri sci- nently anchor a cylinder to the skull for a continuous urea), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), and stump- recording of neuronal activity; (3) They are expensive, tailed monkey (Macaca speciosa) have already been particularly in Japan, because of their high mortality used. -

A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2016, 7, 240-251 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2016.74026 A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals Colin G. Scanes Department of Biological Science, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA Received 10 August 2015; accepted 19 April 2016; published 22 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Purpose: The present study examined the putative relationship between circulating concentra- tions of glucose and log10 body weight in a large sample size (270) of wild species but with domes- ticated animals excluded from the analyses. Methods: A data-set of plasma/serum concentration of glucose and body weight in mammalian species was developed from the literature. Allometric re- lationships were examined. Results: In contrast to previous reports, no overall relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was observed across 270 species of mammals (for log10 glu- cose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003). In con- trast, a strong allometric relationship was observed for circulating concentrations of glucose in 2 Primates (for log10 glucose concentration adjusted R = 0.511; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = 0.480). Conclusion: The absence of an allometric relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was unexpected. A strong allometric relationship was seen in Primates. Keywords Glucose, Allometric, Mammals, Primates 1. Introduction Glucose in the blood is the principal energy source for brain functioning and but glucose can be used as the energy source for multiple other tissues. -

The Historical Ecology of Human and Wild Primate Malarias in the New World

Diversity 2010, 2, 256-280; doi:10.3390/d2020256 OPEN ACCESS diversity ISSN 1424-2818 www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Article The Historical Ecology of Human and Wild Primate Malarias in the New World Loretta A. Cormier Department of History and Anthropology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1401 University Boulevard, Birmingham, AL 35294-115, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-205-975-6526; Fax: +1-205-975-8360 Received: 15 December 2009 / Accepted: 22 February 2010 / Published: 24 February 2010 Abstract: The origin and subsequent proliferation of malarias capable of infecting humans in South America remain unclear, particularly with respect to the role of Neotropical monkeys in the infectious chain. The evidence to date will be reviewed for Pre-Columbian human malaria, introduction with colonization, zoonotic transfer from cebid monkeys, and anthroponotic transfer to monkeys. Cultural behaviors (primate hunting and pet-keeping) and ecological changes favorable to proliferation of mosquito vectors are also addressed. Keywords: Amazonia; malaria; Neotropical monkeys; historical ecology; ethnoprimatology 1. Introduction The importance of human cultural behaviors in the disease ecology of malaria has been clear at least since Livingstone‘s 1958 [1] groundbreaking study describing the interrelationships among iron tools, swidden horticulture, vector proliferation, and sickle cell trait in tropical Africa. In brief, he argued that the development of iron tools led to the widespread adoption of swidden (―slash and burn‖) agriculture. These cleared agricultural fields carved out a new breeding area for mosquito vectors in stagnant pools of water exposed to direct sunlight. The proliferation of mosquito vectors and the subsequent heavier malarial burden in human populations led to the genetic adaptation of increased frequency of sickle cell trait, which confers some resistance to malaria. -

Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetic Importance of a Gamete Recognition Gene Zan Reveals a Unique Contribution to Mammalian Speciation

Molecular evolution and phylogenetic importance of a gamete recognition gene Zan reveals a unique contribution to mammalian speciation. by Emma K. Roberts A Dissertation In Biological Sciences Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Robert D. Bradley Chair of Committee Daniel M. Hardy Llewellyn D. Densmore Caleb D. Phillips David A. Ray Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2020 Copyright 2020, Emma K. Roberts Texas Tech University, Emma K. Roberts, May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank numerous people for support, both personally and professionally, throughout the course of my degree. First, I thank Dr. Robert D. Bradley for his mentorship, knowledge, and guidance throughout my tenure in in PhD program. His ‘open door policy’ helped me flourish and grow as a scientist. In addition, I thank Dr. Daniel M. Hardy for providing continued support, knowledge, and exciting collaborative efforts. I would also like to thank the remaining members of my advisory committee, Drs. Llewellyn D. Densmore III, Caleb D. Phillips, and David A. Ray for their patience, guidance, and support. The above advisors each helped mold me into a biologist and I am incredibly gracious for this gift. Additionally, I would like to thank numerous mentors, friends and colleagues for their advice, discussions, experience, and friendship. For these reasons, among others, I thank Dr. Faisal Ali Anwarali Khan, Dr. Sergio Balaguera-Reina, Dr. Ashish Bashyal, Joanna Bateman, Karishma Bisht, Kayla Bounds, Sarah Candler, Dr. Juan P. Carrera-Estupiñán, Dr. Megan Keith, Christopher Dunn, Moamen Elmassry, Dr. -

New Platyrrhine Tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, Illinois 60115

Daniel L. Gebo New platyrrhine tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. U.S.A. Two new primate tali were discovered from the middle Miocene of South America at La Venta, Colombia. IGM-KU 8802 is similar in morphology to Callicebus and Aotus, and is allocated to cf. Aotus dindensis, while IGM-KU Marian Dagosto 8803, associated with a dentition of a new cebine primate, is similar to Saimiri. Both tali differ from the other known fossil platyrrhine tali, Departments of Cell, Molecular, and Dolichocebus and Cebupithecia, and increase our knowledge of the locomotor Structural Biology and Anthropology, diversity of the La Venta primate fauna. hrorthrerestern lJniuersi;v, Euanston, Illinois 60208, U.S.A. Alfred L. Rosenberger Department of Anthropology, L’niuersity of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60680, U.S.A. Takeshi Setoguchi Primate Research Institute, Kyoto C’niniuersiQ,Inuyama Cily, Aichi 484, Japan Received 18 April 1989 Revision received 4 December 1989and accepted 2 1 December 1989 Keywords: Platyrrhini, La Venta, foot bones, locomotion. Journal of Human Evolution (1990) 19,737-746 Introduction Two new platyrrhine tali were discovered at La Venta, Colombia, by the Japanese/American field team working in conjunction with INGEOMINAS (Instituto National de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras) during the field season of 1988. These two fossils add to the rare but growing number of postcranial remains of extinct platyrrhines from the Miocene of South America (Stirton, 1951; Gebo & Simons, 1987; Anapol & Fleagle, 1988; Ford, 1990). They represent the first new primate postcranials to be described from La Venta in nearly four decades. -

New Primate Genus from the Miocene of Argentina

New primate genus from the Miocene of Argentina Marcelo F. Tejedor*†, Ada´ n A. Tauber‡, Alfred L. Rosenberger§¶, Carl C. Swisher IIIʈ, and Marı´aE. Palacios** *Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı´ficasy Te´cnicas, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolucio´n y Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Esquel, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘‘San Juan Bosco,’’ Sarmiento 849, 9200 Esquel, Argentina; ‡Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Fı´sicasy Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Avenida Velez Sarsfield 249, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina; §Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210; ¶Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 11024; ʈDepartment of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854; and **Museo Regional Provincial ‘‘Padre Manuel Jesu´s Molina,’’ Ramo´n y Cajal 51, 9400 Rı´oGallegos, Argentina Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved December 28, 2005 (received for review August 4, 2005) Killikaike blakei is a new genus and species of anthropoid from the of the estuary of the Rio Gallegos river. The stratigraphy is late Early Miocene of southeastern Argentina based on the most divided into two members (6): Estancia La Costa (120 m thick pristine fossil platyrrhine skull and dentition known so far. It is part with 18 fossiliferous levels) and Estancia Angelina (103 m thick of the New World platyrrhine clade (Family Cebidae; Subfamily with four fossiliferous levels). There are two types of volcanic ash Cebinae) including modern squirrel (Saimiri) and capuchin mon- at the locality. -

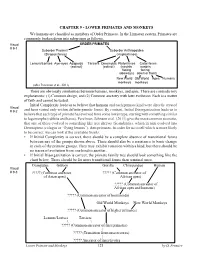

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES AND MONKEYS We humans are classified as members of Order Primates. In the Linnaean system, Primates are commonly broken down into subgroups as follows. Visual ORDER PRIMATES # 9-1 Suborder Prosimii Suborder Anthropoidea (Strepsirrhines) (Haplorrhines) Lemurs/Lorises Aye-ayes Adapoids Tarsiers Omomyids Platyrrhines Catarrhines (extinct) (extinct) (nostrils nostrils facing facing sideways) down or front) New World Old World Apes Humans monkeys monkeys (after Perelman et al., 2011) There are obviously similarities between humans, monkeys, and apes. There are contradictory explanations: (1) Common design, and (2) Common ancestry with later evolution. Each is a matter of faith and cannot be tested. Initial Complexity leads us to believe that humans and each primate kind were directly created Visual # 9-2 and have varied only within definite genetic limits. By contrast, Initial Disorganization leads us to believe that each type of primate has evolved from some lower type, starting with something similar to lagomorphs (rabbits and hares). Perelman, Johnson et al. (2011) give the most common scenario, that one of these evolved to something like tree shrews (Scandentia), which in turn evolved into Dermoptera (colugos or “flying lemurs”), then primates. In order for us to tell which is more likely to be correct, we can look at the available fossils. • If Initial Complexity is correct, there should be a complete absence of transitional forms between any of the groups shown above. There should also be a resistance to basic change in each of the primate groups. They may exhibit variation within a kind, but there should be no traces of evolution from one kind to another. -

Neotropical 10(3).Indd

Neotropical Primates 10(3), December 2002 113 Zoological Nomenclature (2000), and Rylands (2002, p.122) SHORT ARTICLES unfortunately omitted the key word “not” from section (a), which should have read, “…that family-group name is not to be replaced…” The Fourth edition, however, was not final- ized when the manuscript of Groves’ book was completed NEOTROPICAL PRIMATE FAMILY-GROUP NAMES and, unaware that the wording had changed, Groves (2001) REPLACED BY GROVES (2001) IN CONTRAVENTION was therefore quoting from the previous (Third) edition of OF ARTICLE 40 OF THE INTERNATIONAL CODE OF the Code (1985). Although its message remains essentially ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE the same, to set the record straight, this is how Article 40 now reads in the current (Fourth) edition of the Code: Douglas Brandon-Jones Colin P. Groves Article 40. Synonymy of the type genus. 40.1. Validity of family-group names not affected. When Before 1961, it was customary to regard the validity of a the name of a type genus of a nominal family-group taxon family-group name as determined by the recognizability is considered to be a junior synonym of the name of another of its type genus. If the type genus was relegated to the nominal genus, the family-group name is not to be replaced synonymy of another genus, a family-group name with a on that account alone. stem derived from the senior generic synonym was substi- tuted. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature 40.2. Names replaced before 1961. If, however, a family- was then amended to protect the stability of family-group group name was replaced before 1961 because of the names from the potential effects of generic lumping. -

A Preliminary Study for the Future Translocation of a Saimiri Sciureus

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 A Preliminary Study for the Future Translocation of a Saimiri sciureus Troop from Sumak Allpa to Yasuní National Park: Assessing the Habitat Use, Population, and Behavior of a Common Squirrel Monkey Troop in Indillama Kenia French Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Bioinformatics Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Research Methods in Life Sciences Commons, and the Zoology Commons French 1 A Preliminary Study for the Future Translocation of a Saimiri sciureus Troop from Sumak Allpa to Yasuní National Park: Assessing the Habitat Use, Population, and Behavior of a Common Squirrel Monkey Troop in Indillama Saimiri sciureus, Luv Viator, Wikimedia Commons (2007) French, Kenia Academic Director: Silva, Xavier, phD Project Advisor: Vargas, Héctor Tufts University International Relations and Environmental Studies South America, Ecuador, Orellana, Parque Nacional Yasuní, Indillama Submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for Ecuador: Comparative Ecology and Conservation, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2019 French 2 Abstract: Sumak Allpa, an organization specializing in primate rehabilitation, plans to introduce a Common Squirrel Monkey Troop (Saimiri sciureus), the Yasuní Troop, to the Indillama region of Yasuní National Park. This study analyzes the habitat use, population, and behavior of the Saimiri sciureus troop, referred to as the Indillama Troop, already existing in the region, from April 14th to May 4th, 2019. Focal and scan observation techniques were used to observe the troop’s behavior, and EasyTrails on an iPhone 7 was used to record GPS data.