The Babylonian System 17'")

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Namzitara FS Kilmer

Offprint from STRINGS AND THREADS A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer Edited by WOLFGANG HEIMPEL and GABRIELLA FRANTZ - SZABÓ Winona Lake, Indiana EISENBRAUNS 2011 © 2011 by Eisenbrauns Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America www.eisenbrauns.com Drawing on the cover and beneath the title on p. iii by Cornelia Wolff, Munich, after C. L. Wooley, Ur Excavations 2 (1934), 105. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Strings and threads : a celebration of the work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer / edited by Wolfgang Heimpel and Gabriella Frantz-Szabó. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57506-227-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn. 2. Music—Middle East—History and criticism. 3. Music archaeology— Middle East. I. Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn. II. Heimpel, Wolfgang. III. Frantz-Szabó, Gabriella. ML55.K55S77 2011 780.9—dc22 2011036676 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. †Ê Contents Preface .............................................................. vii Abbreviations ......................................................... ix GUITTY AZARPAY The Imagery of the Manichean ‘Call’ on a Sogdian Funerary Relief from China ................ 1 DOMINIQUE COLLON Chinless Wonders ................................ 19 JERROLD S. COOPER Puns and Prebends: The Tale of Enlil and Namzitara. 39 RICHARD L. CROCKER No Polyphony before A.D. 900! ...................... 45 DANIEL A. FOXVOG Aspects of Name-Giving in Presargonic Lagash ........ 59 JOHN CURTIS FRANKLIN “Sweet Psalmist of Israel”: The Kinnôr and Royal Ideology in the United Monarchy .............. 99 ELLEN HICKMANN Music Archaeology as a Field of Interdisciplinary Research ........................ -

ANIMAL SACRIFICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION The

CHAPTER FOURTEEN ANIMAL SACRIFICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION JOANN SCURLOCK The relationship between men and gods in ancient Mesopotamia was cemented by regular offerings and occasional sacrifices of ani mals. In addition, there were divinatory sacrifices, treaty sacrifices, and even "covenant" sacrifices. The dead, too, were entitled to a form of sacrifice. What follows is intended as a broad survey of ancient Mesopotamian practices across the spectrum, not as an essay on the developments that must have occurred over the course of several millennia of history, nor as a comparative study of regional differences. REGULAR OFFERINGS I Ancient Mesopotamian deities expected to be fed twice a day with out fail by their human worshipers.2 As befitted divine rulers, they also expected a steady diet of meat. Nebuchadnezzar II boasts that he increased the offerings for his gods to new levels of conspicuous consumption. Under his new scheme, Marduk and $arpanitum were to receive on their table "every day" one fattened ungelded bull, fine long fleeced sheep (which they shared with the other gods of Baby1on),3 fish, birds,4 bandicoot rats (Englund 1995: 37-55; cf. I On sacrifices in general, see especially Dhorme (1910: 264-77) and Saggs (1962: 335-38). 2 So too the god of the Israelites (Anderson 1992: 878). For specific biblical refer ences to offerings as "food" for God, see Blome (1934: 13). To the term tamid, used of this daily offering in Rabbinic sources, compare the ancient Mesopotamian offering term gimi "continual." 3 Note that, in the case of gods living in the same temple, this sharing could be literal. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

3 a Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36

3 A Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36 3.1 Introduction CCs may be classified according to a number of characteristics. Jagersma (2010, pp. 687-705) gives a detailed description of Sumerian CCs arranged according to the types of constituents that may function as S or PC. Jagersma’s description is the most detailed one ever written about CCs in Sumerian, and particularly, the parts on clauses with a non-finite verbal form as the PC are extremely insightful. Linguistic studies on CCs, however, discuss the kind of constituents in CCs only in connection with another kind of classification which appears to be more relevant to the description of CCs. This classification is based on the semantic properties of CCs, which in turn have a profound influence on their grammatical and pragmatic properties. In this chapter I will give a description of CCs based mainly on the work of Renaat Declerck (1988) (which itself owes much to Higgins [1979]), and Mikkelsen (2005). My description will also take into account the information structure of CCs. Information structure is understood as “a phenomenon of information packaging that responds to the immediate communicative needs of interlocutors” (Krifka, 2007, p. 13). CCs appear to be ideal for studying the role information packaging plays in Sumerian grammar. Their morphology and structure are much simpler than the morphology and structure of clauses with a non-copular finite verb, and there is a more transparent connection between their pragmatic characteristics and their structure. 3.2 The Classification of Copular Clauses in Linguistics CCs can be divided into three main types on the basis of their meaning: predicational, specificational, and equative. -

Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2008 A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Craig, Leah Whitehead, "A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature" (2008). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 106. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/106 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of Western Kentucky University Spring, 2008 Approved by: _________________________________ _________________________________ -

Generation Count in Hittite Chronology 73

071_080.qxd 13.02.2004 11:54 Seite 71 G E N E R A T I O N C O U N T I N H I T T I T E C H R O N O L O G Y Gernot Wilhelm* In studies on Ancient Near Eastern chronology of three participants who voted for the high Hittite history has often been considered a corner- chronology without hesitation (ÅSTRÖM 1989: 76). stone of a long chronology. In his grandiose but – At a colloquium organized by advocates of an as we now see – futile attempt to denounce the ultra-low chronology at Ghent, another hittitolo- Assyrian Kinglist as a historically unreliable source gist, B ECKMAN 2000: 25, deviated from the main- for the Assyrian history of the first half of the 2nd stream by declaring that from his viewpoint, “the millennium B.C., L ANDSBERGER 1954: 50 only Middle Chronology best fits the evidence, although briefly commented on Hittite history. 1 A. Goetze, the High Chronology would also be possible”. however, who at that time had already repeatedly Those hittitologists who adhered to the low defended a long chronology against the claims of chronology (which means, sack of Babylon by the followers of the short chronology (GOETZE Mursili I: 1531) had to solve the problem of 1951, 1952), filled the gap and supported Lands- squeezing all the kings attested between Mursili I berger’s plea for a long chronology, though not as and Suppiluliuma I into appr. 150 years, provided excessively long as Landsberger considered to be that there was agreement on Suppiluliuma’s likely. -

The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State

Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Frontmatter More information The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State From the middle of the third millennium bc until the coming of Cyrus the Great, southwestern Iran was referred to in Mesopotamian sources as the land of Elam. A heterogenous collection of regions, Elam was home to a variety of groups, alternately the object of Mesopotamian aggres- sion, and aggressors themselves; an ethnic group seemingly swallowed up by the vast Achaemenid Persian empire, yet a force strong enough to attack Babylonia in the last centuries bc. The Elamite language is attested as late as the Medieval era, and the name Elam as late as 1300 in the records of the Nestorian church. This book examines the formation and transforma- tion of Elam’s many identities through both archaeological and written evidence, and brings to life one of the most important regions of Western Asia, re-evaluates its significance, and places it in the context of the most recent archaeological and historical scholarship. d. t. potts is Edwin Cuthbert Hall Professor in Middle Eastern Archaeology at the University of Sydney. He is the author of The Arabian Gulf in Antiquity, 2 vols. (1990), Mesopotamian Civilization (1997), and numerous articles in scholarly journals. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Frontmatter More information cambridge world archaeology Series editor NORMAN YOFFEE, University of Michigan Editorial board SUSAN ALCOCK, University of Michigan TOM DILLEHAY, University of Kentucky CHRIS GOSDEN, University of Oxford CARLA SINOPOLI, University of Michigan The Cambridge World Archaeology series is addressed to students and professional archaeologists, and to academics in related disciplines. -

“Going Native: Šamaš-Šuma-Ukīn, Assyrian King of Babylon” Iraq

IRAQ (2019) Page 1 of 22 Doi:10.1017/irq.2019.1 1 GOING NATIVE: ŠAMAŠ-ŠUMA-UKĪN, ASSYRIAN KING OF BABYLON By SHANA ZAIA1 Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is a unique case in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: he was a member of the Assyrian royal family who was installed as king of Babylonia but never of Assyria. Previous Assyrian rulers who had control over Babylonia were recognized as kings of both polities, but Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s father, Esarhaddon, had decided to split the empire between two of his sons, giving Ashurbanipal kingship over Assyria and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn the throne of Babylonia. As a result, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is an intriguing case-study for how political, familial, and cultural identities were constructed in texts and interacted with each other as part of royal self- presentation. This paper shows that, despite Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s familial and cultural identity as an Assyrian, he presents himself as a quintessentially Babylonian king to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. To do so successfully, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn uses Babylonian motifs and titles while ignoring the Assyrian tropes his brother Ashurbanipal retains even in his Babylonian royal inscriptions. Introduction Assyrian kings were recognized as rulers in Babylonia starting in the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (744– 727 BCE), who was named as such in several Babylonian sources including a king list, a chronicle, and in the Ptolemaic Canon.2 Assyrian control of the region was occasionally lost, such as from the beginning until the later years of Sargon II’s reign (721–705 BCE) and briefly towards the beginning of Sennacherib’s reign (704–681 BCE), but otherwise an Assyrian king occupying the Babylonian throne as well as the Assyrian one was no novelty by the time of Esarhaddon’s kingship (680–669 BCE). -

The Mesopotamian Netherworld Through the Archaeology of Grave Goods and Textual Sources in the Early Dynastic III Period to the Old Babylonian Period

UO[INOIGMUKJ[ 0LATE The Mesopotamian Netherworld through the Archaeology of Grave Goods and Textual Sources in the Early Dynastic III Period to the Old Babylonian Period A B N $EEP3HAFTOF"URIALIN&OREGROUNDWITH-UDBRICK"LOCKINGOF%NTRANCETO#HAMBERFOR"URIAL 3KELETON ANDO "URIAL 3KELETONNikki Zwitser Promoter: Prof. Dr. Katrien De Graef Co-promoter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Bretschneider Academic Year 2016-1017 Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Master of Arts: Archaeology. Preface To the dark house, dwelling of Erkalla’s god, to the dark house which those who enter cannot leave, on the road where travelling is one-way only, to the house where those enter are deprived of light, where dust is their food, clay their bread. They see no light, they dwell in darkness. Many scholars who rely on literary texts depict the Mesopotamian netherworld as a bleak and dismal place. This dark portrayal does, indeed, find much support in the Mesopotamian literature. Indeed many texts describe the afterlife as exceptionally depressing. However, the archaeological study of grave goods may suggest that there were other ways of thinking about the netherworld. Furthermore, some scholars have neglected the archaeological data, while others have limited the possibilities of archaeological data by solely looking at royal burials. Mesopotamian beliefs concerning mortuary practices and the afterlife can be studied more thoroughly by including archaeological data regarding non-royal burials and textual sources. A comparison of the copious amount of archaeological and textual evidence should give us a further insight in the Mesopotamian beliefs of death and the netherworld. Therefore, for this study grave goods from non-royal burials, literature and administrative texts will be examined and compared to gain a better understanding of Mesopotamian ideas regarding death and the netherworld. -

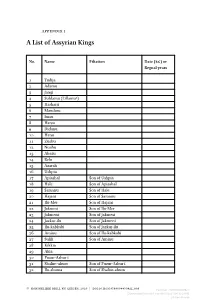

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Urnamma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 1999 Urnamma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition Flückiger-Hawker, Esther Abstract: This book presents new standard editions of all the hitherto known hymns of Urnamma, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur (fl. 2100 B.C.), and adds new perspectives to the compositions and development of the genre of Sumerian royal hymns in general. The first chapter (I) is introductory in nature (historical background, the reading of the name Urnamma, Sumerian royal hymns). The second chapter (II) presents a general survey of Urnamma’s hymnic corpus, including arguments for a broader definition of Sumerian royal hymns and an attempt at classifying the non-standard orthography found in Urnamma’s hymns. The third chapter (III) deals with correlations of Urnamma’s hymns with other textual sources pertaining to him. A fourth chapter (IV) is devoted to aspects of continuity and change in royal hymnography by analyzing the Urnamma hymns in relation to other royal hymns and related genres. A discussion of topoi of legitimation and kingship and narrative materials in different text types during different periods of time and other findings concerning statues, stelas and royal hymns addnew perspectives to the ongoing discussion of the original setting of royal hymns. Also, reasons are given why a version of the Sumerian King List may well be dated to Urnamma and the thesis advanced that Išmēdagan of Isin was not only an imitator of Šulgi but also of Urnamma. The final of the chapter IV shows that Urnamma A, also known as Urnamma’s Death, uses the language of lamentation literature and Curse of Agade which describe the destruction of cities, and applies it to the death of a king.