Assurbanipal at Der

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

Neo-Assyrian Treaties As a Source for the Historian: Bonds of Friendship, the Vigilant Subject and the Vengeful King�S Treaty

WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY Sources, Problems, and Approaches Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Helsinki on September 22-25, 2014 Edited by G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger THE NEO-ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT 2019 STATE ARCHIVES OF ASSYRIA STUDIES Published by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki in association with the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Project Director Simo Parpola VOLUME XXX G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger (eds.) WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY SOURCES, PROBLEMS, AND APPROACHES THE NEO- ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT State Archives of Assyria Studies is a series of monographic studies relating to and supplementing the text editions published in the SAA series. Manuscripts are accepted in English, French and German. The responsibility for the contents of the volumes rests entirely with the authors. © 2019 by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki and the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research All Rights Reserved Published with the support of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Set in Times The Assyrian Royal Seal emblem drawn by Dominique Collon from original Seventh Century B.C. impressions (BM 84672 and 84677) in the British Museum Cover: Assyrian scribes recording spoils of war. Wall painting in the palace of Til-Barsip. After A. Parrot, Nineveh and Babylon (Paris, 1961), fig. 348. Typesetting by G.B. Lanfranchi Cover typography by Teemu Lipasti and Mikko Heikkinen Printed in the USA ISBN-13 978-952-10-9503-0 (Volume 30) ISSN 1235-1032 (SAAS) ISSN 1798-7431 (PFFAR) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. vii Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi, Raija Mattila, Robert Rollinger, Introduction .............................. -

Theodore KWASMAN and Simo PARPOLA, Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part I: Tiglath-Pileser III Through Esarhaddon

Jesho/(DS)590/rev/1-3 6/19/03 2:38 PM Page 1 Theodore KWASMAN and Simo PARPOLA, Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part I: Tiglath-Pileser III through Esarhaddon. State Archives of Assyria VI. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1991. 370, xliv pp., 32 b/w photos. $85.00 (cloth). ISBN 951-570- 093-0. $63.00 (paper). ISBN 951-570-092-2. Raija MATTILA, Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part II: Assurbanipal Through Sin-·arru-i·kun. State Archives of Assyria XIV. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 2002. 382, xxx pp., 17 b/w photos. $101.00/€84.00 (cloth). ISBN 951-570-483-9. $78.00/ €65.00 (paper). ISBN 951-570-481-2. Due to the complete lack of evidence, it is highly likely that no collection of laws was ever compiled in the Neo-Assyrian period. Whatever the reason for the want of this text genre, it was not the result of unfamiliarity with the subject matter: Both the Codex Hammurapi and the Middle-Assyrian Laws were available in Neo-Assyrian libraries. The question whether such law collections were ever meant to actually mirror or regulate contemporary legal practice has nourished the scholarly debate for many years, and the com- parison between the law collections and the extant legal documents constitutes a focal point of the research, especially for the Old Babylonian period. There can be no doubt that the uncertainty about the “Sitz im Leben” of the available law collections hampers their appli- ance to the understanding of the actual practice of law. -

Simo Parpola's

© Otto Lehto, 2008 Parpola’s ‘Tree of Life’ Revisited: Mysteries and Myths of Assyrian Kabbalah 1. Introduction If we want to understand the concept of a ‘Tree of Life,’ we have to make a distinction between two approaches to the same issue. On the one hand, the Tree is a universal symbol of human cultures everywhere, represented in myths and iconography as well as sagas and fairy tales. On the other hand, there exists the more specifically esoteric meaning behind the obvious and more ‘vulgar’ or commonplace interpretations. It is this view that stands behind the mystical conceptions of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. In the motifs of Assyrian, Canaanite and, more broadly, Middle Eastern religions the Tree figures as part of early Semitic (as well as non-Semitic) cultures and their symbolism. The common perception has tied this idea of a life-giving Tree with various forms of ‘fertility cults’ and polytheistic agrarian ritual practice. Simo Parpola, in his 1993 article “The Assyrian Tree of Life”,1 strived to question this established viewpoint, by offering a complementary analysis of the Assyrian tree as a symbol of an early form of ‘Kabbalistic’ mystical knowledge which would not only stand as a bridge between the so-called earlier ‘Oriental’ polytheism and later, Abrahamic 2 monotheism, but also offer a novel explanation of the roots of Tree imagery in Medieval Jewish mysticism. My aims here are complex. The precise question of the correctness of Parpola’s genealogical account does not primarily concern me. It seems to rely on a matter of faith until conclusive evidence is found one way or the other. -

Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars*

BASELLO E LAM AND BABYLONIA : THE EVIDENCE OF THE CALENDARS GIAN PIETRO BASELLO Napoli Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars * Pochi sanno estimare al giusto l’immenso benefizio, che ogni momento godiamo, dell’aria respirabile, e dell’acqua, non meno necessaria alla vita; così pure pochi si fanno un’idea adeguata delle agevolezze e dei vantaggi che all’odierno vivere procura il computo uniforme e la divisione regolare dei tempi. Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, 1892 1 Babylonians and Elamites in Venice very historical research starts from Dome 2 just above your head. Would you a certain point in the present in be surprised at the sight of two polished Eorder to reach a far-away past. But figures representing the residents of a journey has some intermediate stages. Mesopotamia among other ancient peo- In order to go eastward, which place is ples? better to start than Venice, the ancient In order to understand this symbolic Seafaring Republic? If you went to Ven- representation, we must go back to the ice, you would surely take a look at San end of the 1st century AD, perhaps in Marco. After entering the church, you Rome, when the evangelist described this would probably raise your eyes, struck by scene in the Acts of the Apostles and the golden light floating all around: you compiled a list of the attending peoples. 3 would see the Holy Spirit descending If you had an edition of Paulus Alexan- upon peoples through the preaching drinus’ Sã ! Ğ'ã'Ğ'·R ğ apostles. You would be looking at the (an “Introduction to Astrology” dated at 12th century mosaic of the Pentecost 378 AD) 4 within your reach, you should * I would like to thank Prof. -

Melammu: the Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge

Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Nina Ruge, Matthias Schemmel, Kai Surendorf Scientific Board Markus Antonietti, Antonio Becchi, Fabio Bevilacqua, William G. Boltz, Jens Braarvik, Horst Bredekamp, Jed Z. Buchwald, Olivier Darrigol, Thomas Duve, Mike Edmunds, Fynn Ole Engler, Robert K. Englund, Mordechai Feingold, Rivka Feldhay, Gideon Freudenthal, Paolo Galluzzi, Kostas Gavroglu, Mark Geller, Domenico Giulini, Günther Görz, Gerd Graßhoff, James Hough, Man- fred Laubichler, Glenn Most, Klaus Müllen, Pier Daniele Napolitani, Alessandro Nova, Hermann Parzinger, Dan Potts, Sabine Schmidtke, Circe Silva da Silva, Ana Simões, Dieter Stein, Richard Stephenson, Mark Stitt, Noel M. Swerdlow, Liba Taub, Martin Vingron, Scott Walter, Norton Wise, Gerhard Wolf, Rüdiger Wolfrum, Gereon Wolters, Zhang Baichun Proceedings 7 Edition Open Access 2014 Melammu The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Edited by Markham J. Geller (with the cooperation of Sergei Ignatov and Theodor Lekov) Edition Open Access 2014 Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Proceedings 7 Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the Melammu Project, held in Sophia, Bulgaria, September 1–3, 2008. Communicated by: Jens Braarvig Edited by: Markham J. Geller Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Beatrice Hermann, Linda Jauch -

Two Weights from Temple N at Tell Mardikh-Ebla, Syria: a Link Between Metrology and Cultic Activities in the Second Millennium Bc?

TWO WEIGHTS FROM TEMPLE N AT TELL MARDIKH-EBLA, SYRIA: A LINK BETWEEN METROLOGY AND CULTIC ACTIVITIES IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM BC? E. Ascalone and L. Peyronel Università di Roma“La Sapienza” The study of ancient Near Eastern metrology is part of the Lower Town (Matthiae 1985: pl. 54; a specific field of research that offers the possibil- 1989a: 150–52, fig. 31, pls. 105, 106), not far from ity to connect information from economic texts the slope of the Acropolis, to the east of the sacred with objects that were used in the pre-monetary area of Ishtar (Temple P2, Monument P3 and the system either for everyday exchange operations Cistern Square with the favissae).1 It was prob- or for “international” commercial transactions. ably built at the beginning of Middle Bronze I (ca. The importance of an approach that takes into 2000–1900 BC) and was destroyed at the end of consideration metrological standards with all the Middle Bronze II, around 1650–1600 BC. The technical matters concerned, as well as the archaeo- temple is formed by a single longitudinal cella logical context of weights and the relationships (L.2500) with a low, 4 m thick mudbrick bench between specimens and other broad functional along the rear wall (M.2501), while the north classes of materials (such as unfinished objects, (M.2393) and south (M.2502) walls are 3 m thick. unworked stones or lumps of metals, administra- The cella is 7.5 m wide and measures 12 m on the tive indicators, and precious items), has been noted preserved long side. -

The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State

Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Frontmatter More information The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State From the middle of the third millennium bc until the coming of Cyrus the Great, southwestern Iran was referred to in Mesopotamian sources as the land of Elam. A heterogenous collection of regions, Elam was home to a variety of groups, alternately the object of Mesopotamian aggres- sion, and aggressors themselves; an ethnic group seemingly swallowed up by the vast Achaemenid Persian empire, yet a force strong enough to attack Babylonia in the last centuries bc. The Elamite language is attested as late as the Medieval era, and the name Elam as late as 1300 in the records of the Nestorian church. This book examines the formation and transforma- tion of Elam’s many identities through both archaeological and written evidence, and brings to life one of the most important regions of Western Asia, re-evaluates its significance, and places it in the context of the most recent archaeological and historical scholarship. d. t. potts is Edwin Cuthbert Hall Professor in Middle Eastern Archaeology at the University of Sydney. He is the author of The Arabian Gulf in Antiquity, 2 vols. (1990), Mesopotamian Civilization (1997), and numerous articles in scholarly journals. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Frontmatter More information cambridge world archaeology Series editor NORMAN YOFFEE, University of Michigan Editorial board SUSAN ALCOCK, University of Michigan TOM DILLEHAY, University of Kentucky CHRIS GOSDEN, University of Oxford CARLA SINOPOLI, University of Michigan The Cambridge World Archaeology series is addressed to students and professional archaeologists, and to academics in related disciplines. -

Andrew George, What's New in the Gilgamesh Epic?

What’s new in the Gilgamesh Epic? ANDREW GEORGE School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Summary. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic exists in several different versions. There were at least two versions current during the Old Babylonian period, and no doubt a similar situation obtained later in the second millennium BC, when versions of the epic were copied out in Anatolia, Syria and Palestine, as well as in Mesopotamia proper. But the best-known version is the one called “He who saw the Deep”, which was current in the first-millennium libraries of Assyria and Babylonia. Because this text was so much copied out in antiquity we keep finding more of it, both in museums and in archaeological excavation. This means that editions and translations of the epic must regularly be brought up to date. Some of the more important new passages that are previously unpublished are presented here in translation. WHAT THERE IS It was a great pleasure to be able to share with the Society at the symposium of 20 September 1997 some of the results of my work on the epic of Gilgamesh. My paper of this title was given without a script and was essentially a commentary on the slides that accompanied it. The written paper offered here on the same subject tells the story from the standpoint of one year later. Being the written counterpart of an oral presentation, I hope it may be recognized at least as a distant cousin of the talk given in Toronto. I should say at the outset that my work has been concerned primarily with the textual material in the Akkadian language, that is to say, with the Babylonian poems. -

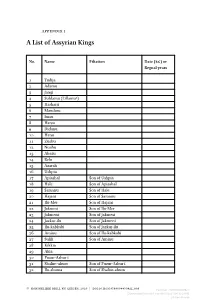

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years