Suggested List of Contents for Phd-Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nordic Energy Technologies

Nordic Energy Technologies nBge A lIn A sustAInABle noRdIC eneRgy futuRe Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 energy Research and Innovation systems in The nordic Region 4 2.1 Describing Nordic Energy Innovation Systems 4 2.1.1 The Nordic Energy Mix 4 2.1.2 Energy Research and Innovation Systems in The Nordic Region 6 2.2 Assessing Nordic Energy Research and Innovation Systems 13 2.2.1 Framework Conditions 13 2.2.2 Energy Research and Innovation Performance 16 Publications, citations and patents 17 Technology deployment and diffusion 19 3 transnational Cooperation 23 3.1 Nordic Cooperation 23 3.2 Cooperation with Adjacent Areas 24 3.2.1 Cooperation with the Baltic Countries 24 3.2.2 European Research Area (ERA) 24 3.3 Emerging Economies 26 3.3.1 Russia 26 3.3.2 China 28 4 Concluding Remarks 30 5 Bibliography 32 Appendix 1: The noria-energy Project Portfolio 34 2 Nordic Energy Technologies ENABLING A SUSTAINABLE NORDIC ENERGY FUTURE Amund Vik and Benjamin Donald Smith, Nordic Energy Research LISTf o abbreViations CCS Carbon Capture and Storage CHP Combined Heat and Power COP15 UN Climate Summit in Copenhagen 2009 DTU Technical University of Denmark EPO European Patent Office ERA European Research Area ERA-NET European Research Area Network EU European Union EUDP Danish Energy Development and Demonstration Programme GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green House Gasses IEA International Energy Agency IPCC UN International Panel on Climate Change IPR Intellectual Property Rights KTH Royal Institute of Technology NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NER Nordic -

Annual Report 2013

Annual report 2013 1 RESULTS AND ACTIVITIES 2013 Content Key figures 2013 3 Part 5 | Reporting – the Energy Fund 35 The CEO speaks 4 2012 and 2013 Enova’s main objective 36 Part 1 | Enova’s outlook 5 Objectives and results of the Energy Fund 38 Green competitiveness 6 Management of the Energy Fund’s resources 40 New energy and climate technology 41 Part 2 | Enova’s activities 9 Climate reporting 52 Social responsibility 10 In-depth reporting 54 Organization 10 Energy results 54 Management 12 Funding level 55 Energy results by project category 56 Portfolio composition 58 Part 3 | Market descriptions 13 Activities 62 Enova – market team player 14 International 65 Indicators 14 Geographical distribution and the largest Renewable heating: 67 16 projects From new establishment to growth Tasks outside the Energy Fund 70 Industry and non-industrial plants and facilities: 18 More companies are cooperating with Enova Energy Technology Data Exchange (ETDE) 70 Non-residential buildings: Intelligent Energy Europe (IEE) 70 20 Energy smart buildings for the future Natural gas 70 Residential buildings: 22 From advice to action Part 6 | Reporting – the Energy Fund New energy and climate technology: 71 24 An innovation perspective 2001-2011 Bioenergy: Energy results and allocations 2001-2011 72 26 Small steps towards a stronger market Climate reporting 78 Part 4 | New energy and climate Appendices 80 27 technology Consultation submissions 81 New technology for the future’s non-residential 28 Publications 81 buildings Definitions and explanation of terminology 82 Symbol key Investigated Renewable Industry Interaction Advicing New energy and Financing Non-residential climate technology buildings Graphs/tables Renewable heating Projects Resedential buildings 2 Key figures 2013 30% RENEWABLE HEATING 5% 1% RESIDENTIAL RENEWABLE BUILDINGS P O W E R PRODUCTION 1,4 TWh In 2013, Enova supported projects with a total energy result of 1.4 TWh through the Energy Fund, distributed over energy efficiency measures, conversion and increased utilization of renewable energy. -

A Comparison of the Environmental Impact of Vertical Farming, Greenhouses and Food Import a Case Study for the Norwegian Vegetable Market

University College Ghent 2017 - 2018 Campus Mercator Henleykaai 84 9000 Ghent Hogeschool Gent Campus Mercator Oslo, 04.06.2018 Henleykaai 84 9000 Gent A comparison of the environmental impact of vertical farming, greenhouses and food import A case study for the Norwegian vegetable market Student: Klaus De Geyter Education: Business management Specialisation: Environmental Management Company: BySpire Thesis supervisor: Katrijn Cierkens © 2018, Klaus De Geyter. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an automated database, or made public, in any form or by any means, be it electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or in any other way, without the prior written permission of the author. The use or reproduction of certain information from this work is only allowed for personal use and provided the source is acknowledged. Any use for commercial or advertising purposes is prohibited. This bachelor's thesis was made by Klaus De Geyter, a student at University College Ghent, to complete a Bachelor's degree in business management. The positions expressed in this bachelor's thesis are purely the personal point of view of the individual author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion, the official position or the policy of the University College Ghent. © 2018, Klaus De Geyter. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen of enige andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de auteur. Het gebruik of de reproductie van bepaalde informatie uit dit werk is enkel toegestaan voor persoonlijk gebruik en mits bronvermelding. -

NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal Og Ølen

OFFENTLEG INFORMASJON NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal og Ølen Gudsteneste på Romsa, sjå side 6 Kateketen har ordet 2 Springing gjev pusterom! 4 Framleis rom i kyrkja 8 Hausten 2020 2 Bjoa kyrkje 125 år 5 Frå kyrkjeboka 8 Redaksjonspennen 3 Oppgradering av Bjoa kyrkje 5 Gundstenester 10 Tradisjon i 120 år 3 Gudsteneste på Romsa 6 Møte og arrangement 11 Orgelet i Vats kyrkje 100 år 3 Kva er kyrkja? 7 Inspirasjonssamling 12 Konfirmantar Bjoa og Ølen 5 Endeleg søndag på Kårhus 7 1 Redaksjons- Kateketen har ordet Britt Karstensen, kateket. PENNEN Av Steinar Skartland HYRDINGEN: Kyrkjeleg fellesråd har gjennom fleire Ansvarleg: Steinar Skartland år fått ekstra midlar av kommunen Tlf. 908 73 170 Ikkje som planlagt til oppgradering av kyrkjene. Den 8. Epost: [email protected] kyrkja som får gleda av dette er på Bjoa. Bladpengar/gåver til Hyrdingen Det blei plutseleg travelt med haust- Å konfirmera tyder å stadfesta. I Ekstra midlane er redusert vesentleg på konto: 3240.11.17937 og konfirmasjonar i år. Sånn blir det, når konfirmasjonen stadfester Gud gåva i nå, men fellesråd og kyrkjeverje VIPPS nr 53 14 72 ting ikkje går som planlagt. Kanskje dåpen, at me får vera Hans born, at prioriterer bygg og kyrkjegardar så Adr. Skjold kyrkje var det like greitt for nokon, kanskje Han framleis vil vera nær. Sånt sett godt det let seg gjera for å sikra at Kleivavegen 2, 5574 Skjold blei det litt mykje stress for andre, men kan ein nesten seie at me ALLE «blir kyrkjene òg i framtida skal vera tenlege Hans Asbjørn Aasbø talar på ettermiddagsmøtet. -

NVE Energibruksrapport 2011

Energy consumption Energy consumption in mainland Norway 4 2012 RAPPORT Ressursfordeling 1:300 Utbygd Gitt tillatelse/under bygging Står att, utbyggbart Verna Verneplan 1 : 2 000 000 0 80 160 km Energy consumption Energy consumption in mainland Norway Report no. 9/2011 Energy consumption, energy consumption in mainland Norway Published by: Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate Edited by: Energy consumption division Author: Ingrid H. Magnussen, Dag Spilde and Magnus Killingland Printed: in-house Circulation: Cover photo: Graphic by Rune Stubrud, NVE ISBN: 978-82-410-0782-8 Keywords: Energy consumption, energy consumption in mainland Norway Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate Middelthunsgate 29 P.O. Box 5091 Majorstua 0301 OSLO Phone: 22 95 95 95 Fax: 22 95 90 00 Website: www.nve.no May 2011 2 Glossary Term Explanation Norwegian Water Resources and Energy NVE Directorate Consumption of all types of energy products Energy consumption (electricity, district heating, oil, gas etc.) Electricity Electrical power, electrical energy Energy consumed in buildings, industry and Final energy consumption transport in mainland Norway. Excludes energy consumed in the energy sector. Gross energy consumption in mainland Total of final energy consumption and energy Norway consumption in the energy sector. Producers, distributors, retailers etc. of energy, Energy sector oil, gas, district heating, electrical power etc. Producers, distributors, retailers etc. of oil, gas Petroleum sector and refined petroleum products. Energy used in buildings, industrial processes Stationary energy consumption and in the energy sector. Energy for motorised vehicles and means of Energy consumption in transport transport. All types of passenger and goods transport, Transport both private and commercial. -

Norway Maps.Pdf

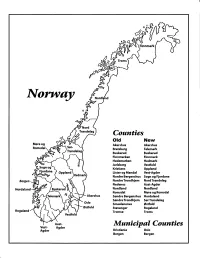

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Register Til Avisutklippene Ved Haugesund Folkebibliotek

Register til Avisutklippene ved Haugesund folkebibliotek Rev. utg. 22. april 2016. Haugesund personalhistorie Personalhistorie: om flere personer. Personalhistorie: Byoriginaler Gårder i Skåre og Haugesund Prisutdelinger, stipend m.v. Aa – Å Her:"mimre" artikler Avdøde haugesundere Personalhistorie: Aa –Å Nekrologer: Avisutklipp over Haugesundere klipt før 1954, innbundet som bøker Personalhistorie - Distriktet Bokn Bremnes - se Bømlo Bømlo: klippes ikke etter 2002 Espevær - se Bømlo Etne Fitjar Fjelberg - se Kvinnherad Førde i Hordaland - se Sveio Halsnøy - se Kvinnherad Hardanger - (er ikke delt videre med unntak av Odda, klippes sjelden) Imsland - se Vindafjord Karmøy – med egen mappe i forkant: Priser og stipend Kinsarvik - se Hardanger Kvinnherad Lofthus - se Hardanger Moster - se Bømlo Nedstrand - se Tysvær Odda Rosendal - se Kvinnherad Røldal Sand - se Suldal Sandeid - se Vindafjord Sauda Skjold, søre - se Tysvær Skjold, nordre se - Vindafjord Skånevik - se Etne og en del under Kvinnherad Stord - klippes ikke etter 2002 Suldal Sunde - se Kvinnherad Personalhistorie - Distriktet – (forts.) - Sveio Tysnes - klippes ikke etter 2002 Tysvær Ullensvang - se Hardanger Uskedal - se Kvinnherad Utsira Valestrand - se Sveio Vats - se Vindafjord Vikebygd, østre del - se Ølen Vikebygd, vestre del - se Sveio Vikedal se Vindafjord Vindafjord Ølen Lokalhistorie - Forskjellige emner (HAUGESUND) Lokalhistorie - emner som ikke kommer inn under de er spesifisert nedenfor: Ikke tidsbestemt - 1879 ordnet i grupper etter omtalte hendelser 1890-1899 do. -

TRANSLATION 1 of 3

114,, Fisheries Pêches TRANSLATION 31 and Oceans et Océans SERIES NO(S) 4888 1 of 3 CANADIAN TRANSLATION OF FISHERIES AND AQUATIC SCIENCES No. 4888 Acid lakes and inland fishing in Norway Results from an interview survey (1974 - 1979) by I.H. Sevaldrud, and I.P. Muniz Original Title: Sure vatn og innlandsfisket i Norge. • Resultater fra intervjuunderseelsene 1974-1979. From: Sur NedbOrs Virkning Pa Skog of Fisk (SNSF-Prosjektet) IR 77/80: 1-203, 1980. Translated by the Translation Bureau (sowF) Multilingual Services Division Department of the Secretary of State of Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre St. John's, NFLD 1982 205 pages typescript Secretary Secrétariat of State d'État MULTILINGUAL SERVICES DIVISION — DIVISION DES SERVICES MULTILINGUES TRANSLATION BUREAU BUREAU DES TRADUCT IONS Iffe LIBRARY IDENTIFICATION — FICHE SIGNALÉTIQUE Translated from - Traduction de Into - En Norwegian English Author - Auteur Iver H. Sevaldrud and Ivar Pors Muniz Title in English or French - Titre anglais ou français Acid Lakes and Inland Fishing in Norway. Results from an Interview Survey (1974 - 1979). Title in foreign language (Transliterate foreign characters) Titre en langue étrangère (Transcrire en caractères romains) Sure vatn og innlandsfisket i Norge. Resultater fra intervjuunders$1(e1sene 1974 - 1979 Reference in foreign language (Name of book or publication) in full, transliterate foreign characters. Référence en langue étrangère (Nom du livre ou publication), au complet, transcrire en caractères romains. Sur nedbç4rs virkning pa skog of fisk (SNSF-prosjektet) Reference in English or French - Référence en anglais ou français • 4eicid Precipitation - Effects on Forest and Fish (the SNSF-project) Publisher - Editeur Page Numbers in original DATE OF PUBLICATION Numéros des pages dans SNSF Project, Box 61, DATE DE PUBLICATION l'original Norway 1432 Aas-NHL, 203 Year Issue No. -

The Future of the Nordic Energy Markets

TABLE OF CONTENTS STRONGER TOGETHER: THE FUTURE OF THE NORDIC ENERGY MARKETS CopyrightA report © Nordic West by Office Nordic 2019. All rights West reserved. Office with input from industry representatives 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................... 6 INTRODUCTION ................................... 12 THEME 1: POWER SUPPLY AND FLEXIBILITY ...... 16 THEME 2: ADVANCED FUELS AND TRANSPORT .. 24 THEME 3: EFFICIENT INTEGRATED ENERGY SYSTEMS .............................................. 31 THEME 4: EU ENERGY UNION AND NORDIC SOLUTIONS .......................................... 39 CLOSING REMARKS ............................. 43 ANNEX: CASE CATALOGUE ................. 45 FOREWORD FOREWORD Climate change is one of the major challenges of our time and for better or for worse, energy plays a key role in it. In 2013, 72% of global greenhouse gas emissions were caused by the energy sector, including energy used for electricity and heating, manufacturing, construction and transportation1. However, a large-scale energy transition is taking place. The world is reducing its dependence on fossil-fuel based energy resources, such as oil and coal, and moving towards low-carbon solutions, harnessing renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power, bio energy and hydropower. Enabled by the advancement of technology and energy in Norway’s gross final energy consumption the associated decline in costs, this transition is was 69.4%5. The relative share of renewable energy progressing rapidly. According to the International in Sweden’s transport fuel consumption in 2017 was Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), one-third 38.6%, and in Finland 18.8% – both well above the of the world’s power capacity in 2018 was from common EU target of 10%6. renewable sources, and nearly two-thirds of the capacity added in 2018 was of renewable origin2. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2014 Financial Key Fgures

Annual Report 2014 Financial key fgures Statkraft AS Group Unit 2014 2013 2012 (restated) 2011 2010 From the income statement Gross operating revenues***** NOK mill 52 254 49 564 37 550 22 449 29 252 Net operating revenues NOK mill 25 805 24 246 18 352 17 161 23 176 EBITDA NOK mill 17 631 16 047 10 492 9 795 15 955 Operating proft NOK mill 13 560 13 002 5 559 6 218 12 750 Share of proft from associates NOK mill 661 1 101 871 898 766 Net fnancial items NOK mill -6 283 -11 592 2 341 -3 642 -917 Proft before tax NOK mill 7 937 2 511 8 771 3 466 12 599 Net proft NOK mill 3 892 208 4 551 40 7 451 Items exluded from underlying business** Unrealised changes in value energy contracts NOK mill 2 396 3 288 -1 030 -1 152 62 Non-recurring items NOK mill 2 053 125 -2 224 -1 035 70 Underlying business** Gross operating revenues NOK mill 48 348 47 458 38 910 22 377 28 990 Net operating revenues NOK mill 20 602 20 545 19 207 18 187 22 721 EBITDA NOK mill 12 132 12 444 11 347 10 880 15 161 Operating proft NOK mill 9 111 9 589 8 813 8 405 12 618 From the balance sheet Property, plant & equipment and intangible assets NOK mill 102 638 104 779 91 788 88 331 80 772 Investments in associates NOK mill 19 027 16 002 15 924 15 080 17 090 Other assets NOK mill 46 152 32 906 38 195 41 514 58 105 Total assets NOK mill 167 817 153 687 145 907 144 925 155 967 Total equity NOK mill 88 059 71 107 62 350 65 655 75 302 Interest-bearing debt NOK mill 36 744 40 377 40 625 37 287 40 486 Capital employed, basic 1) NOK mill 82 244 82 985 71 282 62 546 66 722 Cash flow Net change in cash fow from operating activities NOK mill 6 898 8 106 10 290 9 521 13 577 Dividend for the year to owner (incl. -

Renewable Energy Respecting Nature

Renewable energy respecting nature A synthesis of knowledge on environmental impacts of renewable energy financed by the Research Council of Norway Roel May Kjetil Bevanger Jiska van Dijk Zlatko Petrin Hege Brende NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commissioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all levels, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines.