Thesis Hum 2018 Maedza Ped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Caleb Joseph Cumberland Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the African History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Legal History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cumberland, Caleb Joseph, "Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 249. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/249 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Caleb Joseph Cumberland Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my gratitude to my senior project advisor, Professor Drew Thompson, as without his guidance I would not have been able to complete such a project. -

Qingdao As a Colony: from Apartheid to Civilizational Exchange

Qingdao as a colony: From Apartheid to Civilizational Exchange George Steinmetz Paper prepared for the Johns Hopkins Workshops in Comparative History of Science and Technology, ”Science, Technology and Modernity: Colonial Cities in Asia, 1890-1940,” Baltimore, January 16-17, 2009 Steinmetz, Qingdao/Jiaozhou as a colony Now, dear Justinian. Tell us once, where you will begin. In a place where there are already Christians? or where there are none? Where there are Christians you come too late. The English, Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish control a good part of the farthest seacoast. Where then? . In China only recently the Tartars mercilessly murdered the Christians and their preachers. Will you go there? Where then, you honest Germans? . Dear Justinian, stop dreaming, lest Satan deceive you in a dream! Admonition to Justinian von Weltz, Protestant missionary in Latin America, from Johann H. Ursinius, Lutheran Superintendent at Regensburg (1664)1 When China was ruled by the Han and Jin dynasties, the Germans were still living as savages in the jungles. In the Chinese Six Dynasties period they only managed to create barbarian tribal states. During the medieval Dark Ages, as war raged for a thousand years, the [German] people could not even read and write. Our China, however, that can look back on a unique five-thousand-year-old culture, is now supposed to take advice [from Germany], contrite and with its head bowed. What a shame! 2 KANG YOUWEI, “Research on Germany’s Political Development” (1906) Germans in Colonial Kiaochow,3 1897–1904 During the 1860s the Germans began discussing the possibility of obtaining a coastal entry point from which they could expand inland into China. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The Emergence of Health & Welfare Policy in Pre-Bismarckian Prussia

The Price of Unification The Emergence of Health & Welfare Policy in Pre-Bismarckian Prussia Fritz Dross Introduction till the German model of a “welfare state” based on compulsory health insurance is seen as a main achievement in a wider European framework of S health and welfare policies in the late 19th century. In fact, health insurance made medical help affordable for a steadily growing part of population as well as compulsory social insurance became the general model of welfare policy in 20th century Germany. Without doubt, the implementation of the three parts of social insurance as 1) health insurance in 1883; 2) accident insurance in 1884; and 3) invalidity and retirement insurance in 1889 could stand for a turning point not only in German but also in European history of health and welfare policies after the thesis of a German “Sonderweg” has been more and more abandoned.1 On the other hand, recent discussion seems to indicate that this model of welfare policy has overexerted its capacity.2 Economically it is based on insurance companies with compulsory membership. With the beginning of 2004 the unemployment insurance in Germany has drastically shortened its benefits and was substituted by social 1 Young-sun Hong, “Neither singular nor alternative: narratives of modernity and welfare in Germany, 1870–1945”, Social History 30 (2005), pp. 133–153. 2 To quote just one actual statement: “Is it cynically to ask why the better chances of living of the well-off should not express themselves in higher chances of survival? If our society gets along with (social and economical) inequality it should accept (medical) inequality.” H.-O. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The German colonial settler press in Africa, 1898-1916: a web of identities, spaces and infrastructure. Corinna Schäfer Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex September 2017 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: Summary As the first comprehensive work on the German colonial settler newspapers in Africa between 1898 and 1916, this research project explores the development of the settler press, its networks and infrastructure, its contribution to the construction of identities, as well as to the imagination and creation of colonial space. Special attention is given to the newspapers’ relation to Africans, to other imperial powers, and to the German homeland. The research contributes to the understanding of the history of the colonisers and their societies of origin, as well as to the history of the places and people colonised. -

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918)

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918) Nuno Lemos Pires1 https://academiamilitar.academia.edu/NunoPires At the onset of the Great War, none of the colonial powers were prepared to do battle in Africa. None had stated their intentions to do so and there were no indications that one of them would take the step of attacking its neighbours. The War in Africa has always been considered a secondary theatre of operations by all conflicting nations but, as well shall see, not by the political discourse of the time. This discourse was important, especially in Portugal, but the transition from policy to strategic action was almost the opposite of what was said, as we shall demonstrate in the following chapters. It is both difficult and deeply simple to understand the opposing interests of the different nations in Africa. It is difficult because they are all quite different from one another. It is also deeply simple because some interests have always been clear and self-evident. But we will return to our initial statement. When war broke out in Europe and in the rest of the World, none of the colonial powers were prepared to fight one another. The forces, the policy, the security forces, the traditions, the strategic practices were focused on domestic conflict, that is, on disturbances of the public order, local and regional upheaval and insurgency by groups or movements (Fendall, 2014: 15). Therefore, when the war began, the warning signs of this lack of preparation were immediately visible. Let us elaborate. First, each colonial power had more than one policy. -

The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 by John Gregory

“Children of the Chain and Rod”: The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 by John Gregory Garratt B.A. in History, May 2009, Elon University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2017 Andrew Zimmerman Professor of History and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that John Gregory Garratt has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of December 9, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “Children of the Chain and Rod”: The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 John Gregory Garratt Dissertation Research Committee: Andrew Zimmerman, Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Dane Kennedy, Elmer Louis Kayser Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member Nemata Blyden, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by John Garratt All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation is a testament to my dissertation director, Andrew Zimmerman. His affability made the academic journey from B.A. to Ph.D more enjoyable than it should have been. Moreover, his encouragement and advice proved instrumental during the writing process. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee. Dane Kennedy offered much needed writing advice in addition to marshalling his considerable expertise in British history. Nemata Blyden supported my tentative endeavors in African history and proffered early criticism to frame the dissertation. -

Fabulous Firsts: Hanover (December 1, 1850) by B

Fabulous Firsts: Hanover (December 1, 1850) by B. W. H. Poole (This article is from the July 5, 1937 issue of Mekeel’s Weekly with images added and minor changes in the text. JFD.) The former kingdom of Hanover, or Hannover as our Teutonic friends spell it, has been a province of Prus- sia since 1866. The second Elector of Hanover became George I of England in 1714 and from that date until 1837 the Electors of Hanover sat on the English throne. When Queen Victoria ascended the throne Ha- nover passed to her uncle the Duke of Cumberland. On his death (Nov. 15, 1851) the blind George V succeeded to the kingdom and he, siding with Austria in 1866, took up arms against Prussia, was de- feated and driven from his throne, and the little kingdom was annexed to Prussia. A year before the death of King Ernest (Duke of Cum- berland) Hanover issued its first postage stamp. This stamp, bearing the facial value of 1 gutegroschen, was placed on sale on December 1, 1850. HANOVER, 1850, 1g Black on Gray Blue (1). Huge to enormous mar- gins incl. bottom right sheet corner, strong paper color, on neat folded cover tied by Emden Dec. 31 circular datestamp Issue 22 - October 5, 2012 - StampNewsOnline.net If you enjoy this article, and are not already a subscriber, for $12 a year you can enjoy 60+ pages a month. To subscribe, email [email protected] The design shows a large open numeral “1”, inscribed “GUTENGR”, in a shield with an arabesque background. -

Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Robert C

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier GreyPlace 1990 Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Robert C. West Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/grey Part of the Earth Sciences Commons, and the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation West, Robert C. (1990). Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Baton Rouge: Department of Geography & Anthropology, Louisiana State University. Geoscience and Man, Volume 28. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in GreyPlace by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pioneers of Modern Geography Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Translated and Edited by Robert C. West GEOSCIENCE AND MAN-VOLUME 28-1990 LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY s 62 P5213 iiiiiiiii 10438105 DATE DUE GEOSCIENCE AND MAN Volume 28 PIONEERS OF MODERN GEOGRAPHY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 https://archive.org/details/pioneersofmodern28west GEOSCIENCE & MAN SYMPOSIA, MONOGRAPHS, AND COLLECTIONS OF PAPERS IN GEOGRAPHY, ANTHROPOLOGY AND GEOLOGY PUBLISHED BY GEOSCIENCE PUBLICATIONS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ANTHROPOLOGY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY VOLUME 28 PIONEERS OF MODERN GEOGRAPHY TRANSLATIONS PERTAINING TO GERMAN GEOGRAPHERS OF THE LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES Translated and Edited by Robert C. West BATON ROUGE 1990 Property of the LfhraTy Wilfrid Laurier University The Geoscience and Man series is published and distributed by Geoscience Publications, Department of Geography & Anthropology, Louisiana State University. -

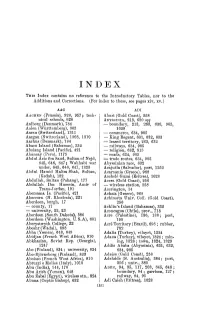

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

Africa and the First World War

Africa and the First World War Africa and the First World War: Remembrance, Memories and Representations after 100 Years Edited by De-Valera NYM Botchway and Kwame Osei Kwarteng Africa and the First World War: Remembrance, Memories and Representations after 100 Years Edited by De-Valera NYM Botchway and Kwame Osei Kwarteng This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by De-Valera NYM Botchway, Kwame Osei Kwarteng and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0546-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0546-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................. x De-Valera N.Y.M. Botchway Section I: Recruitments, Battlefronts and African Responses Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 The Role of the Gold Coast Regiment towards the Defeat of the Germans in Africa during World War I Colonel J. Hagan Chapter Two .............................................................................................