War and Peace in Europe from Napoleon to the Kaiser: the Wars of German Unification, 1864- 1871 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

The Emergence of Health & Welfare Policy in Pre-Bismarckian Prussia

The Price of Unification The Emergence of Health & Welfare Policy in Pre-Bismarckian Prussia Fritz Dross Introduction till the German model of a “welfare state” based on compulsory health insurance is seen as a main achievement in a wider European framework of S health and welfare policies in the late 19th century. In fact, health insurance made medical help affordable for a steadily growing part of population as well as compulsory social insurance became the general model of welfare policy in 20th century Germany. Without doubt, the implementation of the three parts of social insurance as 1) health insurance in 1883; 2) accident insurance in 1884; and 3) invalidity and retirement insurance in 1889 could stand for a turning point not only in German but also in European history of health and welfare policies after the thesis of a German “Sonderweg” has been more and more abandoned.1 On the other hand, recent discussion seems to indicate that this model of welfare policy has overexerted its capacity.2 Economically it is based on insurance companies with compulsory membership. With the beginning of 2004 the unemployment insurance in Germany has drastically shortened its benefits and was substituted by social 1 Young-sun Hong, “Neither singular nor alternative: narratives of modernity and welfare in Germany, 1870–1945”, Social History 30 (2005), pp. 133–153. 2 To quote just one actual statement: “Is it cynically to ask why the better chances of living of the well-off should not express themselves in higher chances of survival? If our society gets along with (social and economical) inequality it should accept (medical) inequality.” H.-O. -

No. 62 Matthew A. Vester, Jacques De Savoie-Nemours

H-France Review Volume 9 (2009) Page 241 H-France Review Vol. 9 (May 2009), No. 62 Matthew A. Vester, Jacques de Savoie-Nemours; l’apanage du Genevois au cœur de la puissance dynastique savoyarde au XVIe siècle. Trans. Eléonore Mazel and Déborah Engel. Geneva: Droz, 2008. Vol. 85, Cahiers d’Humanisme et Renaissance. 360 pp. 47.06 € (pb). ISBN 9872600012119. Review by Orest Ranum, The Johns Hopkins University. The social and political histories of the French frontiers are again becoming subjects for book-length studies. Lucien Febvre’s thesis on the Franche-Comté was the model study for his generation, as Georges Livet’s on Alsace was for the next. The depth of research and the range of themes in these works perhaps explains why Febvre and Livet have been left on the shelves by historians of the current generation; but these monuments to scholarship really do explore all the aspects of center and periphery history for the France of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Boundaries; the Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) Peter Sahlins explores the process by which a general European peace settlement inevitably affected the village communities in the contested territories, in this instance, the Cerdagna. No major princely families, apart from the sovereigns of Spain and France, could effectively lay claim to the region, with the result that, as in some of the provinces in the south of the Spanish Netherlands, diplomats toyed with making what were quite fantastic exchanges of sovereignty, and without regard for the inhabitants. -

Fabulous Firsts: Hanover (December 1, 1850) by B

Fabulous Firsts: Hanover (December 1, 1850) by B. W. H. Poole (This article is from the July 5, 1937 issue of Mekeel’s Weekly with images added and minor changes in the text. JFD.) The former kingdom of Hanover, or Hannover as our Teutonic friends spell it, has been a province of Prus- sia since 1866. The second Elector of Hanover became George I of England in 1714 and from that date until 1837 the Electors of Hanover sat on the English throne. When Queen Victoria ascended the throne Ha- nover passed to her uncle the Duke of Cumberland. On his death (Nov. 15, 1851) the blind George V succeeded to the kingdom and he, siding with Austria in 1866, took up arms against Prussia, was de- feated and driven from his throne, and the little kingdom was annexed to Prussia. A year before the death of King Ernest (Duke of Cum- berland) Hanover issued its first postage stamp. This stamp, bearing the facial value of 1 gutegroschen, was placed on sale on December 1, 1850. HANOVER, 1850, 1g Black on Gray Blue (1). Huge to enormous mar- gins incl. bottom right sheet corner, strong paper color, on neat folded cover tied by Emden Dec. 31 circular datestamp Issue 22 - October 5, 2012 - StampNewsOnline.net If you enjoy this article, and are not already a subscriber, for $12 a year you can enjoy 60+ pages a month. To subscribe, email [email protected] The design shows a large open numeral “1”, inscribed “GUTENGR”, in a shield with an arabesque background. -

Planting Parliaments in Eurasia, 1850–1950

Planting Parliaments in Eurasia, 1850–1950 Parliaments are often seen as Western European and North American institutions and their establishment in other parts of the world as a derivative and mostly defec- tive process. This book challenges such Eurocentric visions by retracing the evo- lution of modern institutions of collective decision-making in Eurasia. Breaching the divide between different area studies, the book provides nine case studies cov- ering the area between the eastern edge of Asia and Eastern Europe, including the former Russian, Ottoman, Qing, and Japanese Empires as well as their succes- sor states. In particular, it explores the appeals to concepts of parliamentarism, deliberative decision-making, and constitutionalism; historical practices related to parliamentarism; and political mythologies across Eurasia. It focuses on the historical and “reestablished” institutions of decision-making, which consciously hark back to indigenous traditions and adapt them to the changing circumstances in imperial and postimperial contexts. Thereby, the book explains how represent- ative institutions were needed for the establishment of modernized empires or postimperial states but at the same time offered a connection to the past. Ivan Sablin is a research group leader in the Department of History at Heidelberg University, Germany. Egas Moniz Bandeira is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia 152. Caste in Early Modern Japan Danzaemon and the Edo Outcaste Order Timothy D. Amos 153. Performing the Politics of Translation in Modern Japan Staging the Resistance Aragorn Quinn 154. Malaysia and the Cold War Era Edited by Ooi Keat Gin 155. -

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A. McFarlane, J.D., Ph.D. Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet 1 Part II: Marshalling and Cadency © Richard A. McFarlane (2015) Marshalling is — 1 Marshalling is the combining of multiple coats of arms into one achievement to show decent from multiple armigerous families, marriage between two armigerous families, or holding an office. Marshalling is accomplished in one of three ways: dimidiation, impalement, and 1 Image: The arms of Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. Blazon: Quarterly: 1st, Gules a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent, on the bend (as an Honourable Augmentation) an Escutcheon Or charged with a Demi-Lion rampant pierced through the mouth by an Arrow within a Double Tressure flory counter-flory of the first (Howard); 2nd, Gules three Lions passant guardant in pale Or in chief a Label of three points Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, Checky Or and Azure (Warren); 4th, Gules a Lion rampant Or (Fitzalan); behind the shield two gold batons in saltire, enamelled at the ends Sable (as Earl Marshal). Crests: 1st, issuant from a Ducal Coronet Or a Pair of Wings Gules each charged with a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent (Howard); 2nd, on a Chapeau Gules turned up Ermine a Lion statant guardant with tail extended Or ducally gorged Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, on a Mount Vert a Horse passant Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper (Fitzalan) Supporters: Dexter: a Lion Argent; Sinister: a Horse Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper. -

Theory of Dynasticism

Theory of Dynasticism Actors, Interests, and Strategies of Medieval Dynasties Sindre Gade Viksand Master’s Thesis Department of Political Science University of Oslo Spring 2017 I II Theory of Dynasticism Actors, Interests, and Strategies of Medieval Dynasties Sindre Gade Viksand III © Sindre Gade Viksand 2017 Theory of Dynasticism. Actors, Interests, and Strategies of Medieval Dynasties Sindre Gade Viksand http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Grafisk Senter AS Word Count: 33 363 IV Abstract Dynasticism has emerged as common concept to refer to the logics of rule in pre-modern international systems. This thesis will attempt both to theorise the concept, as well as developing an ideal-typical framework to analyse one of the most important strategies of the dynasty: the dynastic marriage. It will be argued that the dynamics of dynasticism arose from the changing structures to the European family around AD 1000. These structural changes gave further rise to hierarchies among dynastic actors, interests, and strategies, which will form the basis of a theory of dynasticism. This theory will be utilised to make sense of the various interests involved in creating matrimonial strategies for the dynasty. The argument advanced is that dynastic heirs married according to logics of reproduction; dynastic cadets married for territorial acquisitions; and dynastic daughters married to establish and maintain alliances with other dynasties. These theoretical insights will be used to analyse the marriages of three dynasties in medieval Europe: the Plantagenet, the Capet, and the Hohenstaufen. V VI Acknowledgements In Dietrich Schwanitz’ Bildung. Alles, was man wissen muß, the author notes the danger of appearing to know details about royal families. -

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Imprint Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Publisher: German Museums Association Contributing editors and authors: Working Group on behalf of the Board of the German Museums Association: Wiebke Ahrndt (Chair), Hans-Jörg Czech, Jonathan Fine, Larissa Förster, Michael Geißdorf, Matthias Glaubrecht, Katarina Horst, Melanie Kölling, Silke Reuther, Anja Schaluschke, Carola Thielecke, Hilke Thode-Arora, Anne Wesche, Jürgen Zimmerer External authors: Veit Didczuneit, Christoph Grunenberg Cover page: Two ancestor figures, Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea, about 1900, © Übersee-Museum Bremen, photo: Volker Beinhorn Editing (German Edition): Sabine Lang Editing (English Edition*): TechniText Translations Translation: Translation service of the German Federal Foreign Office Design: blum design und kommunikation GmbH, Hamburg Printing: primeline print berlin GmbH, Berlin Funded by * parts edited: Foreword, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Background Information 4.4, Recommendations 5.2. Category 1 Returning museum objects © German Museums Association, Berlin, July 2018 ISBN 978-3-9819866-0-0 Content 4 Foreword – A preliminary contribution to an essential discussion 6 1. Introduction – An interdisciplinary guide to active engagement with collections from colonial contexts 9 2. Addressees and terminology 9 2.1 For whom are these guidelines intended? 9 2.2 What are historically and culturally sensitive objects? 11 2.3 What is the temporal and geographic scope of these guidelines? 11 2.4 What is meant by “colonial contexts”? 16 3. Categories of colonial contexts 16 Category 1: Objects from formal colonial rule contexts 18 Category 2: Objects from colonial contexts outside formal colonial rule 21 Category 3: Objects that reflect colonialism 23 3.1 Conclusion 23 3.2 Prioritisation when examining collections 24 4. -

Appendix One: the Hundred Years War and Genealogical Charts

APPENDIX ONE: THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR AND GENEALOGICAL CHARTS L. J. Andrew Villalon The Hundred Years War was fought primarily between France and England in the years 1337–1453,1 though (as we shall see in the course of these essays), it spilled over into surrounding regions such as Italy, Spain, the Low Countries, and western Germany. Viewed in a longer perspective, the war was really the last round in a 400-year struggle between two of medieval Europe’s major dynasties to determine which would control much if not all of France, a fact that has led several prominent historians to refer to the con ict as “the second Hundred Years War.”2 On one side stood the Valois Dynasty, a cadet branch of the Capetians who had controlled France since the elevation of Hugh Capet to the kingship in 987.3 Against these Capetian-Valois kings were ranged the Plantagenets, a family that had ruled England since William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, had sailed across the channel in 1066 and seized the throne from its last Anglo-Saxon ruler.4 In the end, after many stunning reversals of fortune, the Capetian- Valois dynasty triumphed. In 1453, its current incumbent, Charles VII (1422–61), expelled his English rivals from all the lands they held on the continent, with the sole exception of the port city of Calais and its 1 Although these are the dates usually assigned to the Hundred Years War, both involve chronological problems of the sort that characterize the con ict. For example, while Edward III began to gather allies for his con ict with the French in 1337, he did not actually launch an attack on that country until 1339 and he of\ cially claimed the French crown only in 1340. -

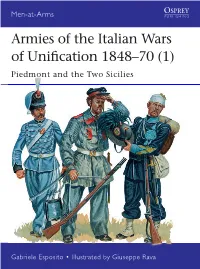

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

League of the Public Weal, 1465

League of the Public Weal, 1465 It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake, nor to succeed in order to persevere. —Charles the Bold Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS 2018! My name is Josh Zucker, and I am excited to be your director for the League of the Public Weal. I am currently a junior studying Systems Engineering and Economics. I have always been interested in history (specifically ancient and medieval history) and politics, so Model UN has been a perfect fit for me. Throughout high school and college, I’ve developed a passion for exciting Model UN weekends, and I can’t wait to share one with you! Louis XI, known as the Universal Spider for his vast reach and ability to weave himself into all affairs, is one of my favorite historical figures. His continual conflicts with Charles the Bold of Burgundy and the rest of France’s nobles are some of the most interesting political struggles of the medieval world. Louis XI, through his tireless work, not only greatly transformed the monarchy but also greatly strengthened France as a kingdom and set it on its way to becoming the united nation we know today. This committee will transport you to France as it reinvents itself after the Hundred Years War. Louis XI, the current king of France, is doing everything in his power to reform and reinvigorate the French monarchy. Many view his reign as tyranny. You, the nobles of France, strive to keep the monarchy weak. For that purpose, you have formed the League of the Public Weal.