Lexical Categories in the Salish and Wakashan Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

1 the Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University

1 The Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University of Victoria, March 2010 Abstract This article offers an overview of the phonological typology and analysis of the Wakashan languages, namely Haisla, Heiltsukvla (Heiltsuk, Bella Bella), Oowekyala, Kwak’wala (Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), Ditidaht (Nitinaht), and Makah. Like other languages of the Northwest Coast of North America, these have many consonants, including several laterals, front and back dorsals, few labials, contrastive glottalization and lip rounding, and a glottal stop with similar distribution to other consonants. Consonant-vowel sequences are characterized by large obstruent clusters, and no hiatus. Of theoretical interest at the segmental level are consonant mutations, positional neutralizations of laryngeal features, vowel-glide alternations, glottalized vowels and glottalized voiced plosives, and historical loss of nasal consonants. Also addressed here are aspects of these languages’ rich prosodic morphology, such as patterns of reduplication and templatic stem modifications, the distribution of Northern Wakashan schwa, alternations in Southern Wakashan vowel length and presence, and the syllabification of all-obstruent words. 1. Introduction The Wakashan language are spoken in what are now British Columbia, Canada, and Washington State, USA. The family comprises a northern branch—Haisla, Heiltsukvla, Oowekyala, and Kwa kwala—and̓ a southern branch—Nuu-chah-nulth, Ditidaht, and Makah— that diverge significantly from each other, but are internally very similar. They are endangered, being spoken natively by about 350 people, out of ethnic populations of about 23,000 whose main language is English. At the same time, most are undergoing active revitalization, with about 1,000 semi-speakers and learners ( First Peoples’ Language Map ). -

33 Contact and North American Languages

9781405175807_4_033 1/15/10 5:37 PM Page 673 33 Contact and North American Languages MARIANNE MITHUN Languages indigenous to the Americas offer some good opportunities for inves- tigating effects of contact in shaping grammar. Well over 2000 languages are known to have been spoken at the time of first contacts with Europeans. They are not a monolithic group: they fall into nearly 200 distinct genetic units. Yet against this backdrop of genetic diversity, waves of typological similarities suggest pervasive, longstanding multilingualism. Of particular interest are similarities of a type that might seem unborrowable, patterns of abstract structure without shared substance. The Americas do show the kinds of contact effects common elsewhere in the world. There are some strong linguistic areas, on the Northwest Coast, in California, in the Southeast, and in the Pueblo Southwest of North America; in Mesoamerica; and in Amazonia in South America (Bright 1973; Sherzer 1973; Haas 1976; Campbell, Kaufman, & Stark 1986; Thompson & Kinkade 1990; Silverstein 1996; Campbell 1997; Mithun 1999; Beck 2000; Aikhenvald 2002; Jany 2007). Numerous additional linguistic areas and subareas of varying sizes and strengths have also been identified. In some cases all domains of language have been affected by contact. In some, effects are primarily lexical. But in many, there is surprisingly little shared vocabulary in contrast with pervasive structural parallelism. The focus here will be on some especially deeply entrenched structures. It has often been noted that morphological structure is highly resistant to the influence of contact. Morphological similarities have even been proposed as better indicators of deep genetic relationship than the traditional comparative method. -

STUDIES in SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Grad

STUDIES IN SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics iii Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for their contributions to my dissertation. First, I must thank the people of Neah Bay, Washington for their hospitality and generosity during my stay there. The staff of the Makah Cultural and Reseach Center and the Makah Language Program merit special recognition for their unwavering support of my project, so thanks to Janine Bowechop, Yvonne Burkett, Cora Buttram, Keely Parker, Theresa Parker, Maria Pascua, and Melissa Peterson. Of all my friends in Neah Bay, I am most indebted to my primary Makah language consultant, Helma Swan Ward, who spent many patient hours answering questions about Makah and sharing her insights about the language with me. My project has benefited greatly from the labors of my dissertation committee at SUNY Buf- falo, Karin Michelson, Matthew Dryer, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. Their insights concerning both analytic matters and organizational details made the dissertation better than it otherwise would have been. Bill Jacobsen, my outside reader, deserves my gratitude for his meticulous reading of the manuscript on short notice, which resulted in many improvements to the final work. Thanks also to Jay Powell, who facilitated my initial contact with the Makah. I gratefully acknowledge funding for my research from the Jacobs Research Funds and the Mark Diamond Research Fund of the Graduate Student Association of the State University of New York at Buffalo. -

Prepositional His and the Development of Morphological Case in Northern Wakashan1

Prepositional his and the development of morphological case in Northern Wakashan1 Katie Sardinha University of British Columbia This paper will present evidence for the historical development of “oblique” and “genitive” case-marking clitics in the Northern Wakashan language family from the Proto- North Wakashan preposition *his and an associated set of person-marking enclitics. The three Upper Northern Wakashan languages (Haisla, Heiltsuk, Oowekyala) are at intermediate stages of a process whereby a remnant of the preposition his/yis together with its associated person- marking enclitics is becoming enclitic to the prosodic word prior to the noun phrase it introduces or replaces; this can be taken as evidence that these languages are moving towards developing case-marking such as that which exists in Kwak’wala. Correspondences between the synchronic distribution and phonology of the Kwak’wala oblique and third-person possessive clitics and that of his/yis prepositional constructions in the Upper Northern Wakashan languages provide additional evidence for an historical relationship. Prior to the development of morphological case, prepositions themselves seem to have been innovated in the Northern Wakashan language branch from verbal and demonstrative roots. This situation indicates a deep syntactic divide, and significant time depth, between the Northern and Southern branches of Wakashan. 1 Introduction The aim of this paper is to develop an historical hypothesis to account for the innovation of two Northern Wakashan syntactic features which are conspicuously absent in the Southern Wakashan branch: the presence of prepositions, and the occurrence of varying degrees of morphological case- marking. More specifically, I will be presenting evidence for two historical 1 I would like to thank my Kwak’wala consultant Ruby Dawson Cranmer for sharing her language with me, my supervisor Henry Davis, and the members of the 2009-2010 UBC Field Methods class. -

Language Contact and the Dynamics of Language: Theory and Implications 10-13 May 2007 Leipzig

Paper for the Symposium Language Contact and the Dynamics of Language: Theory and Implications 10-13 May 2007 Leipzig Rethinking structural diffusion Peter Bakker First draft. Very preliminary version. Please do not quote. May 2007. Abstract Certain types of syntactic and morphological features can be diffused, as in convergence and metatypy, where languages take over such properties from neighboring languages. In my paper I would like to explore the idea that typological similarities in the realm of morphology can be used for establishing historical, perhaps even genetic, connections between language families with complex morphological systems. I will exemplify this with North America, in particular the possible connections between the language families of the Northwest coast/ Plateau and those of the eastern part of the Americas. I will argue on the basis on typological similarities, that (ancestor languages of ) some families (notably Algonquian) spoken today east of the continental divide, were once spoken west of the continental divide. This will lead to a more theoretical discussion about diffusion: is it really possible that more abstract morphological features such as morpheme ordering can be diffused? As this appears to be virtually undocumented, we have to be very skeptical about such diffusion. This means that mere morphological similarities between morphologically complex languages should be taken as evidence for inheritance rather than the result of contact. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 0. Preface Not too long ago, many colleagues in linguistics were skeptical that many were actually due to contact. Now that language contact research has become much more mainstream and central than when I started to work in that field, it is time to take the opposite position. -

On the Origin of Salish, Wakashan, and North

84 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 1 : 1-121 (2008) Available online at www.ata.org.tn Original Synthetic Article On The Origin of Salish, Wakashnan, and North Caucasian Languages Vitaly Shevoroshkin Vitaly Shevoroshkin was born in 1932 in Georgia (then a republic of the USSR). In the years 1951-1974 he lived in Moscow USSR, where he has graduated from the Dept. of Philology of the Moscow University in 1956. When working as a researcher in the USSR Academy of Sciences (1966-1973), he defended two dissertations on linguistics (1964 and 1966). Since 1974, he lives in the USA where he is Professor of Linguistics at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He has published and edited 20 books and wrote over 500 papers on linguistics. He is mostly interested in the problems of distant genetic relationship between different language families. Department of Linguistics, University of Michigan , USA ; E. mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The following paper represents a comparison between the most stable words in two language unities: 1) Salish-Wakashan (North America) and 2) Lezghian group of the North Caucasian family (North Caucasus). This comparison shows that any word/root from the list of basic words in Salish and/or Wakashan precisely matches the appropriate word/root of Lezghian as well as its proto-form in North Caucasian. Such close similarity clearly shows that the Salish-Wakashan languages of North America are related to the North Caucasian languages. We may add that the North Caucasian languages are older, and phonetically more complex, than Salish-Wakashan languages. -

Paper Algonquian, Wiyot, and Yurok: Proving a Distant Genetic Relationship

Algonquian-Ritwan, (Kutenai) and Salish: Proving a distant genetic relationship * Peter Bakker Aarhus University A connection between Algonquian and Salishan was first suggested almost a century ago, and several Americanists have mentioned it or briefly discussed it (Boas, Haas, Sapir, ).i, ;, Swadesh, Thompson, Denny). However, nobody has tried to provide proof for the matter beyond a few suggestive lexical correspondences (Haas, Denny) and typological similarities (Sapir). In my paper I follow the method used by Goddard (1975) and focus on morphology to try and prove a genetic relationship between the two families. The morphological organization of the Salishan and Algonquian verbs are highly similar. Moreover, some of the pertinent grammatical morphemes also show striking formal similarities. In addition, a number of shared quirks between Salishan and Algonquian point to a genetic connection. There is archaeological evidence linking both Algonquian and Ritwan languages with the Columbia Plateau, where Salishan languages dominate, suggesting a shared history of the three groupings in the Columbia River area. Introduction The title of this paper is a clear allusion to Ives Goddard's famous 1975 paper Algonquian, Wiyot, and Yurok: Proving a distant genetic relationship. The genetic relationship between Algonquian and the two Californian languages (together the Ritwan family) was controversial, but is now generally accepted, and Ritwan and Algonquian families are now conceived of as members of the Algic stock. I use, to the extent that this is possible, the same method as Goddard used for Algic. Whereas Goddard compared Proto-Algonquian (hereafter P A) * I am not a Salishanist, neither do I have knowledge of Proto-Algonquian This is a preliminary paper and I hope to receive feedback. -

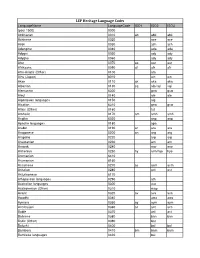

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

![Bibliography of the Wakashan Languages [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8074/bibliography-of-the-wakashan-languages-microform-2988074.webp)

Bibliography of the Wakashan Languages [Microform]

IMAGE EVALUATrON TEST TARGET (MT-3) 1.0 < lU |22 It u^ 110 I.I 1.25 U III 1.6 V] S. <^ <F /] /. AV \:\ ^ iV /A .'•v. 4^. C^ '^I*'* ^^ '/ Photogrdphic 33 WHT MAIN STMIT WHSTiRNY USIO Sciences (716) iTi^soa Corporation CIHM/ICMH CIHIVI/ICMH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Instituta for Historical Microraproductions Institut Canadian da microraproductions historiquas 1980 i Tschnieal and Bibliographic Notas/Notas tachniquaa at bibliographiquat Tha Inatituta haa attamptad to obtain tha baat L'Institut a microfilmi la malllaur axamplaira original copy availabia for filming. Faaturaa of thia qu'il lui a AtA possibia da sa procurar. Las details copy which may ba bibliographically uniqua, da cat axamplaira qui sont paut-Atra uniquas du which may altar any of tha imagaa in tha point da vua bibliographiqua, qui pauvant modifiar raproduction. or which may aignificantly changa una imaga raproduita, ou qui pauvant axigar una tha uaual mathod of filming, ara chackad balow. modification dans la mtthoda normala da filmaga sont indiquAs ci-daaaous. Colourad covara/ Colourad pagas/ D Couvartura da coulaur I I Pagas da coulaur Covars damagad/ r~n Pagas damagad/ I I Couvartura andommagAa Pagas andommagtes Covars rastorad and/or laminatad/ Pagas rastorad and/orand/oi laminatad/ I I D Couvartura rattaurte at/ou palliculAa Pagas rastaurAas at/ou palliculAas Covar titia misting/ Pagas discolourad, stainad or foxad/foxai I I I I La titra da couvartura manqua Pagaa dicolorAas, tachattas ou piquAas Colourad maps/ Pagas datachad/ I I I I Cartas gAographiquas an coulaur Pagas dttachAas Colourad Init (i.a. -

Proof of the Algonquian-Wakashan Relationship

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 1: Proof of the Algonquian-Wakashan relationship The first part of the present study, following a general introduction (§ 1), presents a classifi- cation and approximate glottochronological dating for the Algonquian-Wakashan languages (§ 2), a preliminary discussion of regular sound correspondences between Proto-Wakashan, Proto-Nivkh, and Proto-Algic (§ 3), and an analysis of the Algonquian-Wakashan “basic lexi- con” (§ 4). The main novelty of the present article is in its attempt at formal demonstration of a genetic relationship between the Nivkh, Algic, and Wakashan languages, arrived at by means of the standard comparative method, i. e. establishing a system of regular sound cor- respondences between the vocabularies of the compared languages. Proto-Salishan is con- sidered as a remote relative of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan; at the same time, no close (“Mosan”) relationship between Wakashan and Salish has been traced. Additionally, lexical correspondences between Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan, and Proto-Salishan are also reviewed. The conclusion is that no genetic relationship exists be- tween Chukchi-Kamchatkan, on the one hand, and Algonquian-Wakashan, languages (Nivkh included), on the other hand. Instead, it seems more likely that Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan has borrowed words from Wakashan, Salishan, and Algic (but probably not vice versa; § 5). The Algonquian-Wakashan, Salishan and Chukchi-Kamchatkan common cultural lexicon is also examined, resulting in the identification of numerous “cultural” loans from Wakashan and Salish into Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan. Borrowing from Salishan into Proto-Nivkh was far less intensive, as there are no reliable Nivkh-Wakashan contact words.