Moskee Project Department of Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floristic Inventory of Subalpine Parks in the Coeur D'alene River Drainage, Northern Idaho

FLORISTIC INVENTORY OF SUBALPINE PARKS IN THE COEUR D'ALENE RIVER DRAINAGE, NORTHERN IDAHO by Robert K. Moseley Conservation Data Center December 1993 Idaho Department of Fish and Game Natural Resource Policy Bureau 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost-share Project Idaho Panhandle National Forests Idaho Department of Fish and Game ABSTRACT Treeless summits and ridges in the otherwise densely forested mountains of northern Idaho, have a relatively unique flora compared with surrounding communities. Although small in area, these subalpine parks add greatly to the biotic diversity of the regional landscape and are habitats for several vascular taxa considered rare in Idaho. I conducted a floristic inventory of 32 parks in the mountains of the Coeur d'Alene River drainage and adjacent portions of the St. Joe drainage. The project is a cooperative one between the Idaho Department of Fish and Game's Conservation Data Center and the Idaho Panhandle National Forest. The subalpine park flora contains 151 taxa representing 97 genera in 34 families. Carex are surprisingly depauperate, in terms of both numbers and cover, as is the alien flora, which is comprised of only three species. I discovered populations of five rare species, including Carex xerantica, which is here reported for Idaho for the first time. Other rare species include Astragalus bourgovii, Carex californica, Ivesia tweedyi, and Romanzoffia sitchensis. Stevens Peak is the highest summit and is phytogeographically unique in the study area. It contains habitat for six taxa occurring nowhere else in the study area, all having high-elevation cordilleran or circumboreal affinities. -

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

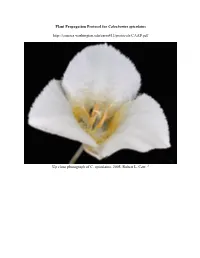

Plant Propagation Protocol for Calochortus apiculatus http://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/CAAP.pdf Up close photograph of C. apiculatus. 2005, Robert L. Carr. 2 Photograph of C. apiculatus growth form. 2005, Robert L. Carr. 2 TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Liliaceae1 Name: Family Common Lily Name: Scientific Names Genus: Calochortus1 Species/Epithet: Apiculatus1 Species Authority: Baker1 Varieties N/A Sub-species N/A Cultivar N/A Common N/A Synonym(s) Common Name(s) Pointedtip Mariposa Lily1 Baker’s Mariposa2 Three-Spot Mariposa Lily2 Species Code: CAAP1 GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Found in the United States of America in north eastern Washington as well as an isolated population in Yakima Co., northern Idaho, and in Montana. In Canada, this species is found in British Columbia and Alberta. Ecological distribution Typically found in meadows and grassy slopes, as well as open coniferous forests and valleys.5,8,11 Climate and elevation Found in dry to moist soils between 440-2500 meters.4,8,10 range Local habitat and Doesn’t commonly associate with specific species of plants. abundance Plant strategy type / Seral, occurring in areas without a lot of disturbance, but also no late successional stage successional growth. Plant characteristics Perennial forb, leaves grow basally, flower is white with yellowish, hairy throat.5,8 PROPAGATION DETAILS Ecotype N/A Propagation Goal Plants (Bulbs)3 Propagation Method Seed3 Product Type Container (plug)6 Stock Type 4” pots, D-Pots seeding flats3,6 Time to Grow 1 year6 Target Specifications First year bulb, 3-8mm diameter6 Propagule Collection Collect whole fruits (capsules) right before or after ripening (for most Instructions Calochortus species, this is May through August).6 Propagule Seeds last 5-6 years in the environment but may last longer if stored in a Processing/Propagule fridge. -

Waterton Lakes National Park • Common Name(Order Family Genus Species)

Waterton Lakes National Park Flora • Common Name(Order Family Genus species) Monocotyledons • Arrow-grass, Marsh (Najadales Juncaginaceae Triglochin palustris) • Arrow-grass, Seaside (Najadales Juncaginaceae Triglochin maritima) • Arrowhead, Northern (Alismatales Alismataceae Sagittaria cuneata) • Asphodel, Sticky False (Liliales Liliaceae Triantha glutinosa) • Barley, Foxtail (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Hordeum jubatum) • Bear-grass (Liliales Liliaceae Xerophyllum tenax) • Bentgrass, Alpine (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Podagrostis humilis) • Bentgrass, Creeping (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Agrostis stolonifera) • Bentgrass, Green (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Calamagrostis stricta) • Bentgrass, Spike (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Agrostis exarata) • Bluegrass, Alpine (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa alpina) • Bluegrass, Annual (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa annua) • Bluegrass, Arctic (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa arctica) • Bluegrass, Plains (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa arida) • Bluegrass, Bulbous (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa bulbosa) • Bluegrass, Canada (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa compressa) • Bluegrass, Cusick's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa cusickii) • Bluegrass, Fendler's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa fendleriana) • Bluegrass, Glaucous (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa glauca) • Bluegrass, Inland (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa interior) • Bluegrass, Fowl (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa palustris) • Bluegrass, Patterson's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa pattersonii) • Bluegrass, Kentucky (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa pratensis) • Bluegrass, Sandberg's (Poales -

Early Vegetal Succession Following Large Northern Rocky Mountain Wildfires

Early Vegetal Succession Following Large Northern Rocky Mountain Wildfires L. JACK LYON AND PETER F. STICKNEyl INTRODUCTION ~LDFIRE is a naturally recurring phenomenon in the forests of the Northern Rockies. Historical accounts of earliest explorations contain references to areas denuded by fire, and the massive forest fires of this century have been documented. Written records before 1800 are sketchy, but charcoal in the ground, burned stumps, and fire scars in tree cross sections provide evidence of a forest-fire history predating the oldest living vegetation in the North ern Rockies. Thus, it is generally accepted that these forests have evolved in the presence of repeated fires. Despite this evolutionary concept, recognition of the ecological sig nificance of fire is relatively recent and not yet well defined. Much of the literature treats fire as the external disturbance of an otherwise stable system. By implication, forest succession becomes evidence of ecosystem resilience or ability to recover from outside disturbance, and predictive models tend to assume the classic concept of succes sion in which early seral plants modify the site to their own exclusion and thereby permit establishment of interseral and climax species. Our data suggest that this is a poor conceptual model for forest suc cession in the Northern Rockies. 'Research Wildlife Biologist and Associate Plant Ecologist, respectively, USDA Forest Serv ice, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, Utah 84401, stationed in Missoula, Montana, at the Forestry Sciences Laboratory, maintained in cooperation with the 355 L. JACK LYON AND PETER F. STICKNEY As an alternative, we believe that fire should be treated as an in ternal perturbation of a generally stable system. -

An Investigation of Putative Hybridization Between Calochortus Selwayensis and Calochortus Apiculatus (Liliaceae)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 An investigation of putative hybridization between Calochortus selwayensis and Calochortus apiculatus (Liliaceae) George Henry Wittler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wittler, George Henry, "An investigation of putative hybridization between Calochortus selwayensis and Calochortus apiculatus (Liliaceae)" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6749. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6749 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -V s AN INVESTIGATION OF PUTATIVE HYBRIDIZATION BETWEEN CALOCHORTUS SELWAYENSIS AND CALOCHORTUS APICULATUS (LILIACEAE) By George H. Wittier III B.A., Carleton College, 1971 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by : "7^ K - Chaij^an, Board of Exæminers Dean,Graduate School Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37550 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Botany Alberta 2015: in This Issue Botany Bliss in Waterton Lakes National Park

No. 79 March 2016 Iris The Alberta Native Plant Council Newsletter Botany Alberta 2015: In This Issue Botany Bliss in Waterton Lakes National Park Botany Alberta 2015: Sandy McAndrews Waterton Lakes National Park ................................1 Botany Alberta 2015 took place in Montane, and Foothills Parkland. Herbarium on the Move: Waterton Lakes National Park (WLNP) These four subregions provide enough Royal Alberta Museum .................4 between June 19 and 21, the weekend variability for the existence of 45 of the summer solstice. This superb separate vegetation communities, Dwarf Woolly-heads in national park is located in the far which provide habitat for more than Southeastern Alberta ...................6 southwest corner of Alberta, at the 1,000 (more than half) of Alberta’s Tongue-Tied in Latin: Canada-United States border. In 1932, vascular plant species. According to R to Z ..............................................8 together with Glacier National Park Parks Canada (2012), 50 of those species in Montana, WLNP became part of are nationally rare. Non-vascular News and Events .........................10 the world’s frst International Peace species are abundant too. And, as one Rare Plant Conservation: Park (IPP), the Waterton-Glacier of the warmest places in Alberta, the 29th Workshop International Peace Park. In 1995, park had high potential to see lots of & AGM Registration ....................11 this IPP was designated a UNESCO fowering plants in June. A perfect place World Heritage Site because of its for botany enthusiasts! biogeographical signifcance (Parks Canada 2012). The biogeological signifcance of WLNP is derived largely from its location. Situated at the height of the continent in the Western Cordillera of North Look for more information America, it is infuenced by maritime on the ANPC’s website. -

ICBEMP Analysis of Vascular Plants

APPENDIX 1 Range Maps for Species of Concern APPENDIX 2 List of Species Conservation Reports APPENDIX 3 Rare Species Habitat Group Analysis APPENDIX 4 Rare Plant Communities APPENDIX 5 Plants of Cultural Importance APPENDIX 6 Research, Development, and Applications Database APPENDIX 7 Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the Interior Columbia River Basin 122 APPENDIX 1 Range Maps for Species of Conservation Concern These range maps were compiled from data from State Heritage Programs in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada. This information represents what was known at the end of the 1994 field season. These maps may not represent the most recent information on distribution and range for these taxa but it does illustrate geographic distribution across the assessment area. For many of these species, this is the first time information has been compiled on this scale. For the continued viability of many of these taxa, it is imperative that we begin to manage for them across their range and across administrative boundaries. Of the 173 taxa analyzed, there are maps for 153 taxa. For those taxa that were not tracked by heritage programs, we were not able to generate range maps. (Antmnnrin aromatica) ( ,a-’(,. .e-~pi~] i----j \ T--- d-,/‘-- L-J?.,: . ey SAP?E%. %!?:,KnC,$ESS -,,-a-c--- --y-- I -&zII~ County Boundaries w1. ~~~~ State Boundaries <ii&-----\ \m;qw,er Columbia River Basin .---__ ,$ 4 i- +--pa ‘,,, ;[- ;-J-k, Assessment Area 1 /./ .*#a , --% C-p ,, , Suecies Locations ‘V 7 ‘\ I, !. / :L __---_- r--j -.---.- Columbia River Basin s-5: ts I, ,e: I’ 7 j ;\ ‘-3 “. -

Park S Canada, Frank W Einschenk

Photos : Parks Canada, Frank Weinschenk 2018 Waterton Wildflower Festival Welcome to the 15th Annual Waterton Wildflower Festival TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME Thanks for coming to the 15th annual Waterton Wildflower Festival! The Wildflower Festival was the 2016 finalist of the Alto Award in the category: Welcome 2 Where the Wild Things Go: Wildlife Outstanding Sustainable Tourism. You are in for a treat as you wander the Wildflower Capital of Canada. Free Admission to Parks Canada’s Movement Project 8 Places for Youth 17 and Under 3 Oh Deer! 9 The festival celebrates the values of this national park and helps participants to cherish the natural wonders Why is Waterton the Wildflower Northern Leopard Frog that are here. As a program of The Waterton Park Capital of Canada? 3 Reintroduction 9 Community Association, a not for profit, the festival blooms a little bigger and brighter each year, and Protecting Landscapes 3 Protecting the Park from Aquatic we must shout our thanks to wonderful community Charlie Russell 4 Invasive Species 9 partners and supporters like Parks Canada, The Nature Conservancy of Canada, the Chamber of Commerce and other local groups. This year Rare Plants of Waterton 5 More Waterton Adventures 10 – 11 we would like to give special thanks to The Bear Mountain Motel and the Waterton Authors at the Festival 6 Festival Special Events and Lake Lodge for helping us during the festival this year!! Turning the Tide Against Invasive Programs 12 Come to the Waterton Community Centre (WCC) and say hi! Plants 6 Festival at a Glance -

Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants

Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants June 1, 2011 By Scott Mincemoyer Montana Natural Heritage Program Helena, MT This checklist of Montana vascular plants is organized by Division, Class and Family. Species are listed alphabetically within this hierarchy. Synonyms, if any, are listed below each species and are slightly indented from the main species list. The list is generally composed of species which have been documented in the state and are vouchered by a specimen collection deposited at a recognized herbaria. Additionally, some species are included on the list based on their presence in the state being reported in published and unpublished botanical literature or through data submitted to MTNHP. The checklist is made possible by the contributions of numerous botanists, natural resource professionals and plant enthusiasts throughout Montana’s history. Recent work by Peter Lesica on a revised Flora of Montana (Lesica 2011) has been invaluable for compiling this checklist as has Lavin and Seibert’s “Grasses of Montana” (2011). Additionally, published volumes of the Flora of North America (FNA 1993+) have also proved very beneficial during this process. The taxonomy and nomenclature used in this checklist relies heavily on these previously mentioned resources, but does not strictly follow anyone of them. The Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants can be viewed or downloaded from the Montana Natural Heritage Program’s website at: http://mtnhp.org/plants/default.asp This publication will be updated periodically with more frequent revisions anticipated initially due to the need for further review of the taxonomy and nomenclature of particular taxonomic groups (e.g. Arabis s.l ., Crataegus , Physaria ) and the need to clarify the presence or absence in the state of some species. -

UBC Library Copy

Relationship Between Vital Attributes of Ktunaxa Plants and Natural Disturbance Regimes in Southeastern British Columbia by Shirley Mah B.S.F., The University of British Columbia, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Faculty of Forestry Department of Forest Sciences We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ......................................................................... ......................................................................... ......................................................................... ......................................................................... THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2000 © Shirley Mah, 2000 ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between plant resources of the Ktunaxa people and the natural disturbance regimes in southeastern British Columbia and how reduced fire frequency may have affected the plant resources. The main objectives were to determine the vital attributes or fire survival strategy for each Ktunaxa plant; validate Rowe’s hypothesis on the relationships between different species groups (set of vital attributes) and fire cycle length for southeastern British Columbia; and predict which Ktunaxa plants would most likely be affected by reduced fire frequency. The proportions of species groups, based on the Ktunaxa plants and their assigned vital attributes, were determined for 13 Biogeoclimatic (BEC) subzone/variants, ranging from low elevation ponderosa pine to subalpine ecosystems. I used a one-way nested ANOVA to test the relationships between species groups and fire cycle length. The data for southeastern British Columbia tended to be consistent with Rowe’s hypothesis. Examples are presented of Ktunaxa plants most likely to be affected by reduced frequency of fire: plants that can resprout from underground parts; plants that produce wind-carried seed; and shade intolerant plants that store seed in the soil. -

Of Families of Idaho

Anotated Checklist 1 CHECKLIST OF VASCULAR PLANTS OF BONNER AND BOUNDARY COUNTIES, IDAHO compiled by Marian J. Fuller, Ph.D in Botany This checklist of Bonner and Boundary counties contains 1382 vascular plant taxa belonging to 109 families and to 460 genera. The families are arranged phylogenetically, not alphabetically. Alphabetical indices of the families and genera are provided. The genera are arranged alphabetically within the each family, and species are arranged alphabetically within the genus. Additional sources and their acronyms: (BLM) = McFarlane, S, Kuhman T. and Johnson, C. 2002. Field Guide to Special Status Plants of the Cottonwood Field Office. (FPNW) = Hitchcock, C. L. and Cronquist, A. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. (PRM). = Kershaw L., A, MacKinnon and J. Pojar; Mousseaux, M.R. 1998. Plants of the Rocky Mountains. (IFG) =Idaho Fish and Game (in house document on plants of three recently acquired wetlands) (IPNF-RPFG) = Mousseaux, M.R, Idaho Panhandle National Forests--Rare Plant Field Guide (original and revised editions). (IPNF-) = Idaho Panhandle National Forests (in house document including K = Kaniksu, P = Priest Lake . (UIH) =University of Idaho Herbarium, Moscow. (USDA) = plants.usda.gov/classification Abbreviations: Br = Bonner County; By = Boundary County; Br and By = collected by MJF; Br and By = collected or notated by others. See additonal sources * = exotic taxon Ida? = maybe first record for Bonner and/or Boundary Counties, many not in FPNW. Explanation of the Components of a Checklist Entry: Maianthemum1 -

VALERIANACEAE Wet Grass Forest Valeriana Dioica

VALERIANACEAE Wet Grass Forest Valeriana dioica - - C wood valerian Valeriana edulis U U - tobacco root VERBENACEAE Verbena bracteata - U - bracted vervain VIOLACEAE Viola adunca U - C early blue violet Viola canadensis U - C Canada violet Viola orbiculata - - U round-leaved violet Viola palustris U - U marsh violet A Vascular Plant Checklist for Lost Trail National Wildlife Refuge Peter Lesica January 2015 The checklist is organized alphabetically by family, genus and RUBIACEAE Wet Grass Forest species. We have not attempted to determine plants to subspecies Galium aparine - U U or varieties. Vascular plant nomenclature follows Lesica, P. cleavers 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Botanical Research Galium boreale - C U Institute of Texas Press, Fort Worth, Texas. northern bedstraw Habitat and Abundance Codes Galium trifidum C - - small bedstraw Wetlands (Wet) are supplied with groundwater greater than what Galium triflorum - - C is supplied to upland habitats. These include the peatland fens sweet-scented bedst raw and carrs as well as ponds, marshes and wet meadows. Riparian SALICACEAE habitats such as wet spruce forests and willow thickets are also Populus balsamifera U - - included. black cottonwood Populus tremuloides C - C Grassland (Grass) include foothills prairie as well as shrubby quaking aspen inclusions on rocky outcrops and roadside habitats. Salix bebbiana C - - Bebb willow Forest (Forest) are dominated by Douglas fir, ponderosa pine and Salix boothii C - - lodgepole pine. Rock outcrops and small openings in the